T

There’s a curious imbalance in the world of art criticism: when writing about prose and verse, we critique the art in the same medium in which it was composed, but this doesn’t hold true for other forms. To put it more simply, we use words to criticize words, but we don’t often use musical notes to criticize musical notes. (I’m using the word “criticize” here to mean “engage rigorously,” not merely to point out weaknesses or flaws. Some criticism is complimentary!) There are a few scattered examples, but for the most part an in-media piece created in conversation with another piece is more of an impressionistic response than a critical one. I’ve long wondered what it would be like to see a rise in medium-based criticism, where a critic completes a sculpture as his criticism of another sculpture, or paints a mural to critique a piece of visual art.

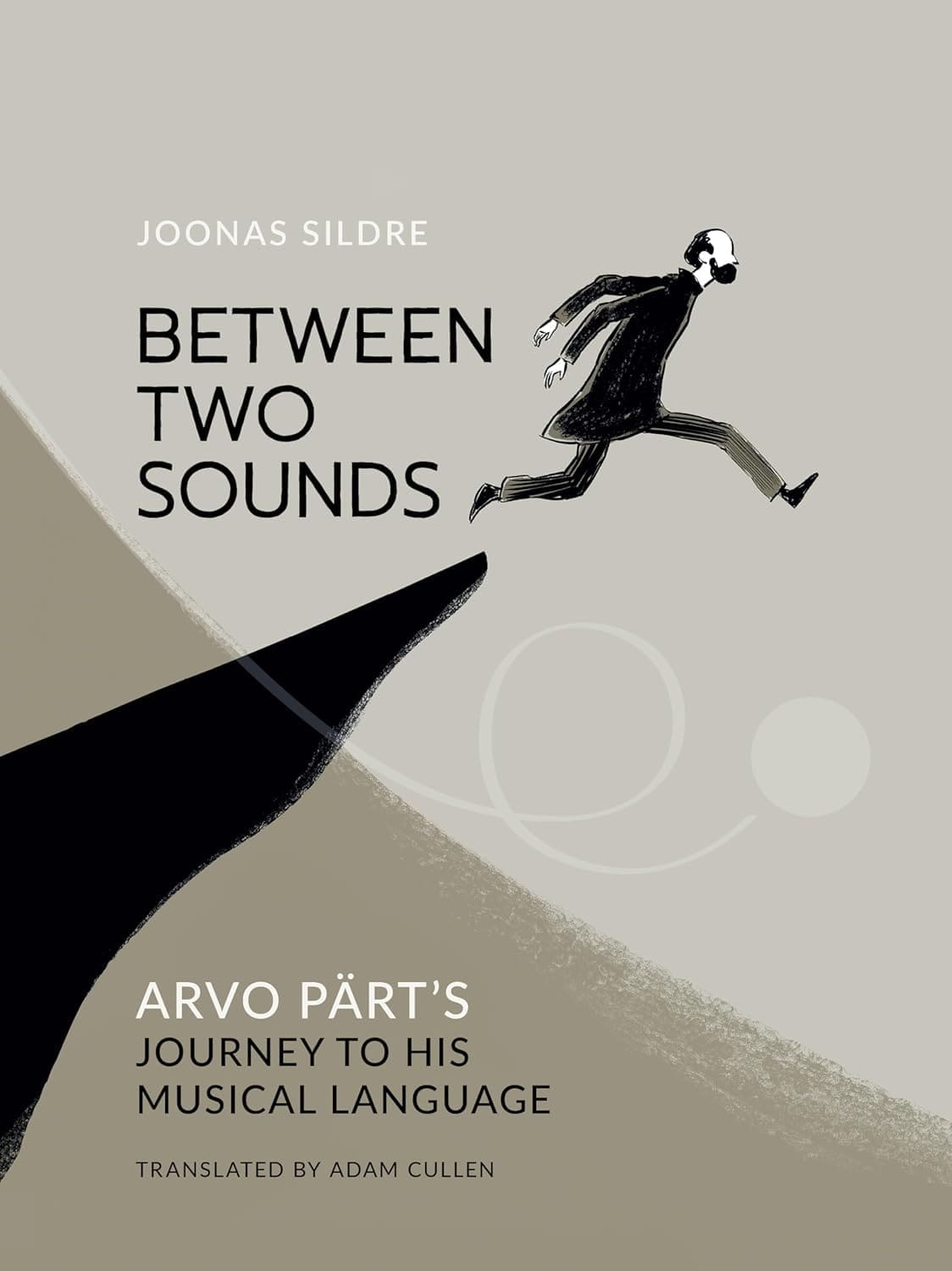

Between Two Sounds, out in September from Plough Books, explores the life and work of the Estonian composer Arvo Pärt. In contemporary classical music, Pärt is one of the best-known names. Between Two Sounds tells the story of how he developed his signature “tintinnabuli” style, which he has also called “holy minimalism.” It is a beautiful and moving story, taking us into some of the darkest moments of the twentieth century, yet illuminated throughout by Pärt’s own spirit of radiant hope and joy.

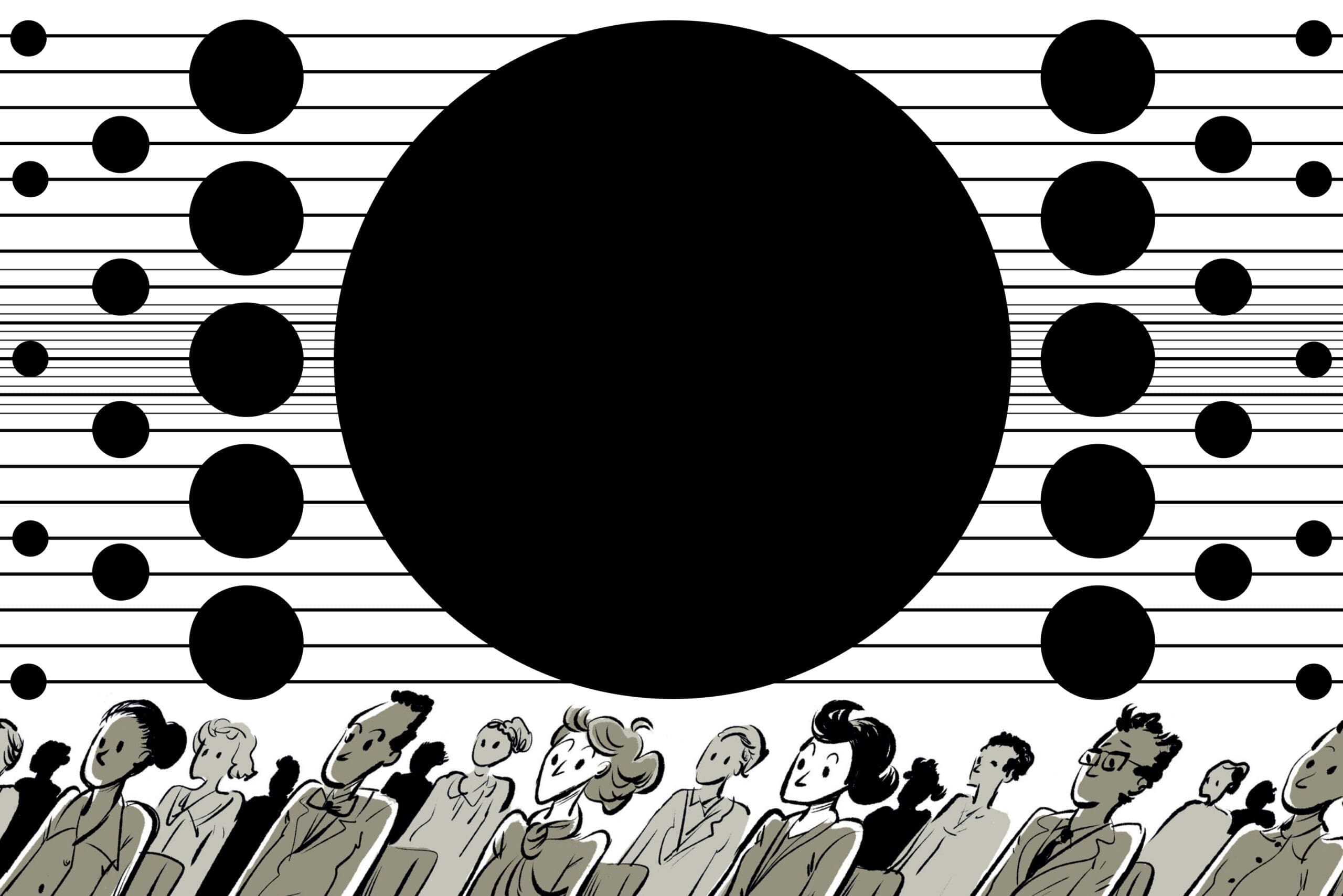

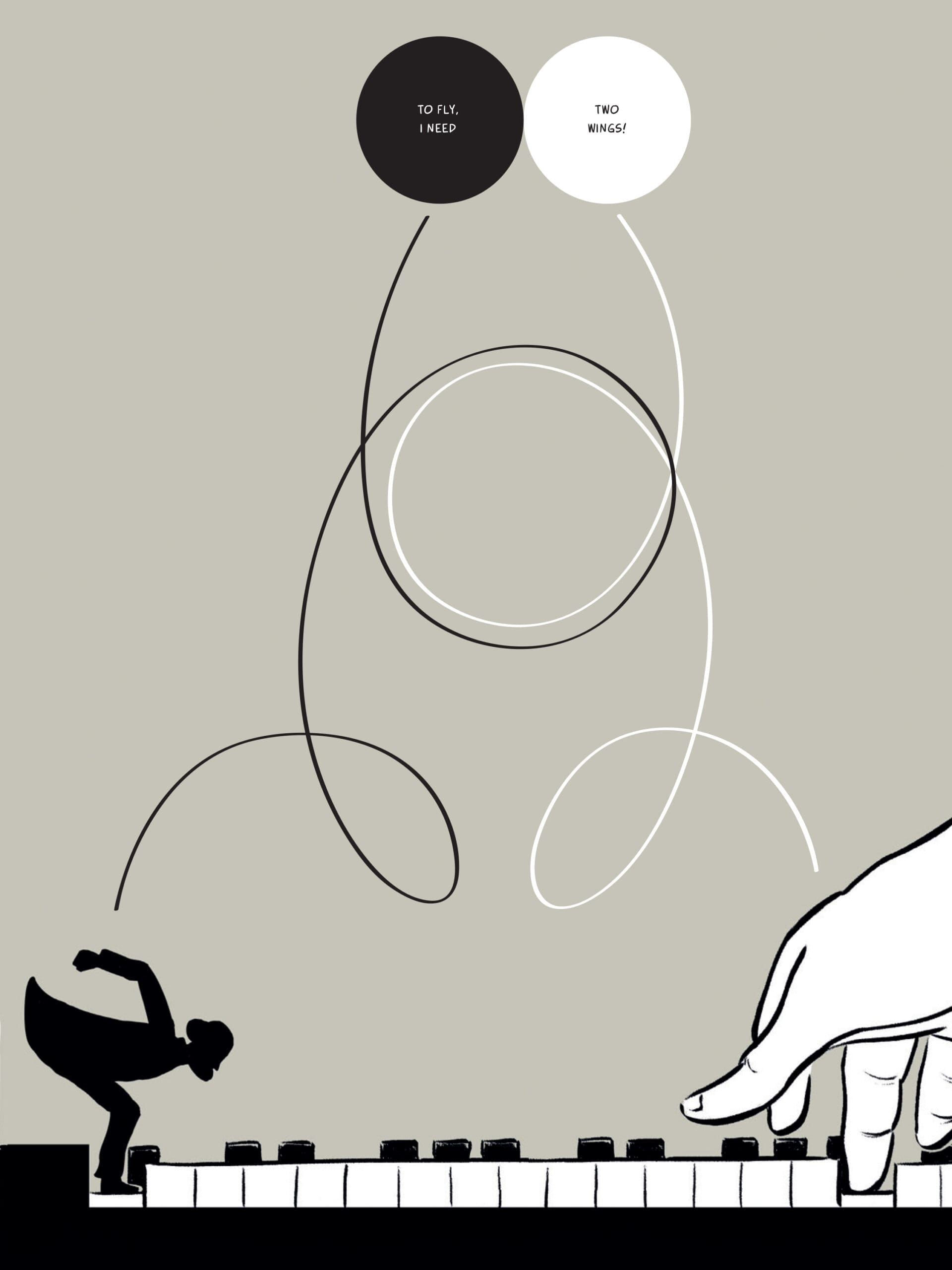

The book is not quite criticism, nor is it written in musical notes. But it comes close to this strange ideal of mine because it offers to us the story of a great musical artist’s life and a “close reading,” if you will, of his techniques—his voices—using not prose-critical writing but comic-book illustrations. The illustrations invoke, through delicate spirals, dots, and loops, the experience of listening to a piece of music. This unique and delightful book offers a rigorous defense of Pärt’s oeuvre in the unexpected form of a graphic novel, and surprisingly it works, opening the world of contemporary classical music—and contemporary criticism—to a new, less prose-oriented audience.

Arvo Pärt was born in 1935 in Paide, Estonia. When he was just five years old, Estonia entered a terrible cycle of conquest and domination. Starting with its takeover by Soviet Russia in 1940, the little nation was occupied by the Third Reich during World War II and was reabsorbed by the USSR in 1944. It remained a part of the USSR until 1991. A series of stark, tenebrous panels in Between Two Sounds evoke the feeling of life in a war-torn Soviet-bloc nation. World War II bombers over Pärt’s hometown drop bombs the shape of the large black dots, a visual motif that will come to represent Pärt’s first “voice.” (More on this later.) In one particularly powerful sequence, the young Pärt discovers that he can listen to music played through the loudspeakers in the public square of Rakvere, where he lives, but when he simply stands under the speakers and listens, he is bullied by other young people. So he begins riding his bicycle in circles, round and round, simply so he can hear the sound of music.

This anecdote reveals much of Pärt’s spirit: tenacious but peaceful, clever, drawn inexorably to beauty. Pärt spent his entire youth and much of his adult life under one oppressive regime or another, a situation that does not lend itself to artistic experimentation. Despite this, he encountered a handful of courageous teachers, composers, and musicians who recognized the young man’s gift and encouraged him to use it to honour reality, not the Soviet state.

From his early childhood, Pärt showed a love of and aptitude for music. He would play his own little tunes on the family piano, but the middle keys were damaged, so he experimented with the highest and lowest notes—a tendency that appears in his mature compositions of the 1970s and 1980s. Throughout the book, illustrator Joonas Sildre incorporates floating dots—some black, some white—into the scenery and backgrounds of the comic panels. These dots, strung along playful, curving, straight, or jagged lines, simulate musical notes and bars, illustrating Pärt’s conviction that music is all around us, in every single sound (including the squeaks of rubber ducks, which play a part in one of his compositions).

For the attentive reader, the juxtaposition of the black dots and the white tells the whole tale of Pärt’s “two sounds.” The black dots, more prominent in the first half of the book, represent the first of his two sounds: Pärt’s effort to find meaning through modern, mathematical compositions, as shown in highly structured pieces like his Nekrolog and Symphonies 1 & 2. They also illustrate the bombs and other angular, aggressive sounds. The first white dot appears deep in the book, on page 78, when Pärt visits an Orthodox cathedral with his friend and hears sacred music. A graceful white circle floats on a smoothly curving line like a track of wind, rather than the straight or sharply curved lines that trail after the black dots. This encounter with sacred music was the root of the crucial second sound that would utterly transform Pärt’s compositions in years to come.

The white dots bring us face to face with Pärt’s deep faith in God. Even in the atheist regime of the USSR, Pärt developed a profound understanding of Christianity. Midway through his life, his single-minded pursuit of musical expression led him to the staggering realization that what he was truly seeking through his art was God. Pärt, along with his second wife, Nora, eventually joined the Orthodox Church.

Pärt heard at last a voice that was at once profoundly aware of reality—including the reality of evil—and calm, at peace, even joyful. He heard a sound that was not afraid of silence.

In 1969 Pärt wandered into a record shop and heard a kind of music that was totally new to him. This music, he learned, was called Gregorian chant. Along with his friend and colleague Kuldar Sink, Pärt sought to learn more about Gregorian chant and other early music—a task made difficult by the fact that the USSR did not allow early music to be played on its channels and jammed the European channels that did play it. But Pärt would not be stopped. He searched out sheet music from friends, acquaintances, libraries, and churches, and, midway through his career, launched on a quest to reinvent his musical voice.

The enchantment of early music for Pärt was that it was “conflict-free.” The music of his world was full of conflict. The bombastic, nostalgic Soviet anthems harped on the struggle between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat, while the atomistic modern music from the West, like twelve-tone, was rife with existential dread. Yet here, in early music, Pärt heard at last a voice that was at once profoundly aware of reality—including the reality of evil—and calm, at peace, even joyful. He heard a sound that was not afraid of silence.

From this moment springs Pärt’s finest work. In the mid-1970s Pärt began to develop his tintinnabuli style, which defines such masterpieces as “Für Alina,” “Spiegel im spiegel,” and (my personal favourite) “Tabula Rasa.” Sildre illustrates the gorgeous unity of the two voices that defines Pärt’s best work in a beautiful, page-wide single panel in which a black dot and a white dot spiral up in a dance from a keyboard while Pärt exclaims, “To fly I need two wings!”

Through Pärt’s conversations with other Estonian and Soviet-bloc musicians, Sildre manages to communicate many of the complex elements of musical theory that describe Pärt’s breakthrough, but he does so in a way that will not alienate readers without a classical musical background. The most important—and most radical—element of Pärt’s musical journey, however, is one that artists of all forms would do well to meditate on: the idea that only through purifying the self can one purify one’s art. When in the book Pärt is asked by an interviewer in 1978 what has changed in his creative process, Pärt replies, “I myself have changed.” The only path to purer, clearer art—art that truly “lets in” the sublime—is to clear one’s soul.

Pärt’s path to these spiritual realizations was not made smoother by the regime he lived under. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, he ran afoul of the Soviet bureaucracy by persisting in writing music that incorporated modernist European techniques. After his clearly Christian piece “Credo” was first performed in 1968, it was banned entirely, and Pärt found himself under rigorous observation by the authorities. In 1980, Pärt and his family were exiled from Estonia and fled to Vienna, and then on to Berlin, where they remained for nearly three decades.

Only through purifying the self can one purify one’s art.

Sildre concludes the story of Between Two Sounds with the Pärt family’s departure from Estonia. From that point on, Pärt continued to hone the astonishing new method he had discovered, in which his two voices blend so closely as to become one. Throughout the end of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first, Pärt’s music has continued to showcase his fascination with mathematical models as well as his theological conviction that divine simplicity is at the core of reality. In many of his pieces, not only do the two voices blend, but the very distinction between sound and silence itself begins to give way.

To capture in visual form this incredible movement in a great composer’s soul is difficult. To capture it in comic panels, using only white, black, and sepia, is remarkable. Yet that is what Sildre has done: in keeping with Pärt’s conviction that at its heart reality is simple, he has distilled the stirring epic of a Soviet-era struggle for an authentically religious artistic voice down to a clear, straightforward, visually streamlined tale.

There are, though, a few moments when the story is unclear: for example, we learn of Pärt’s early marriage to his first wife, Hilde, and then, years later, Pärt marries Nora. What happened to Hilde? We are never told. I did some research, and while there is very limited information available on Pärt’s first marriage, Sildre does little to forestall the reader’s confusion.

But such narrative hitches do not undermine this book’s accomplishment. What we find in Between Two Sounds is simultaneously a biographical account, a historical survey of Estonian music, and a theological exploration of the relationship between the pursuit of God and the practice of art. It is a rare and delightful little treasure, one that will be of interest to anyone intrigued by contemporary art, twentieth-century history, or the question of what it means to pursue God through one’s calling.