T

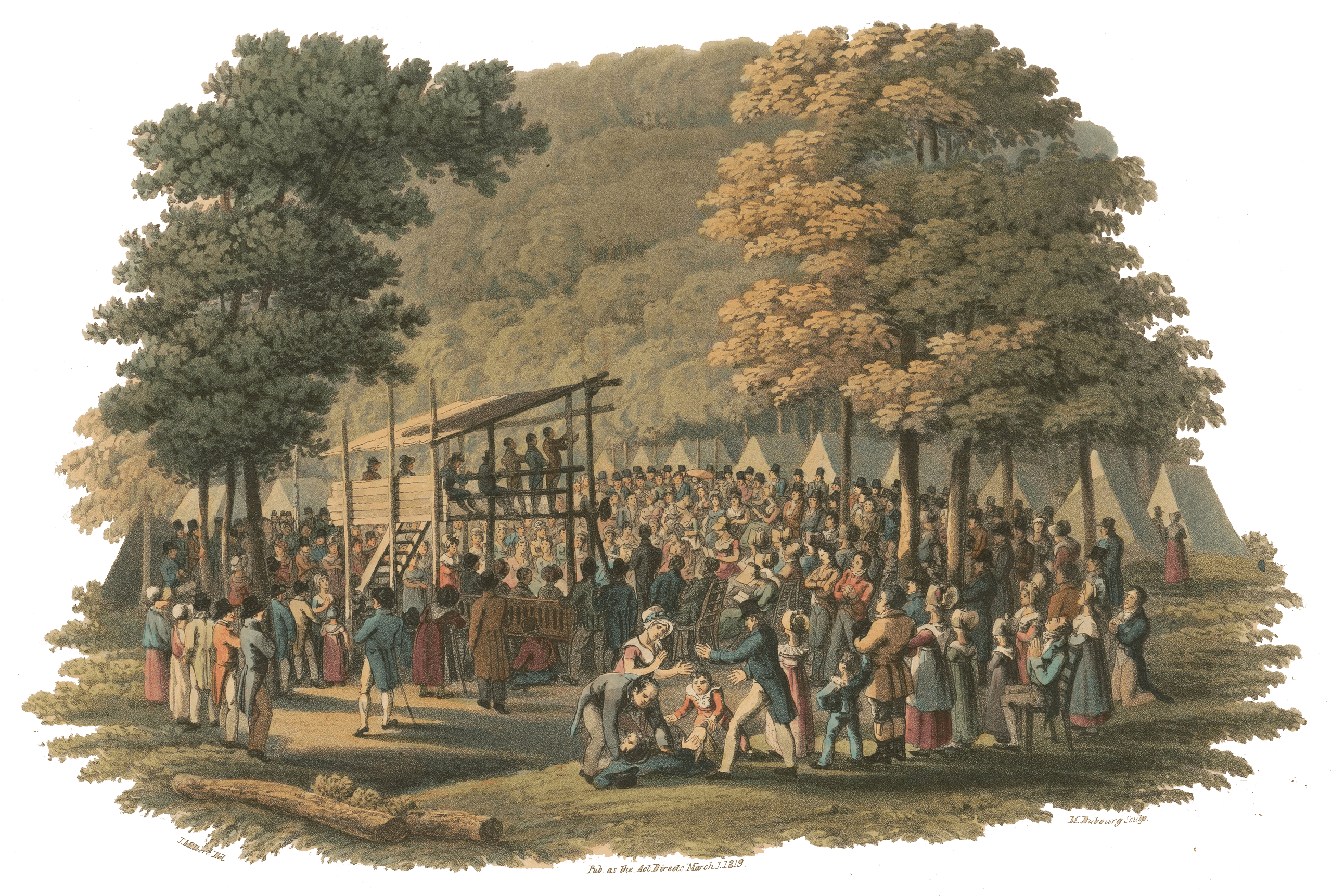

This past spring’s much-noticed revival at Asbury University breathed much-needed calm into the contentious atmosphere of American public life. Here at an institution sponsored by Wesleyan-Holiness Methodists, Gen-Z students with no apparent partisan objectives experienced spiritual renewal marked by reconciliation, repentance, grace, humility, and hope. Although social media rapidly transformed this local event into an international happening, the ego-fixation, demonization, and conspiracy-mongering so prevalent on social media were largely absent among those who pilgrimaged to Wilmore, Kentucky, or who participated vicariously from afar. Significantly, leaders at the university and nearby Asbury Seminary did all in their power to keep the focus on matters of the spirit. They turned aside celebrities who arrived eager to muscle in, they withstood the temptation to view the event as aiding red states or blue states, they kept the focus on prayer, singing, and Scripture. Their counsel to students concentrated on how to move from experiences of grace to works of mercy.

At Asbury, observers could see what had made American Methodism the religious marvel of the nation’s early history. Whether the revival of 2023 will have a lasting impact is of course much too soon to say. By contrast, the long-lasting impact of the Methodist movement that unfolded in the early nineteenth century under the leadership of the eponymous Francis Asbury is beyond dispute. But the legacy of that earlier history is complex. As a spiritual movement, Methodists achieved remarkable success in large part because they kept their message nonpartisan in a nation riven by political-religious conflict. But when the this-worldly convictions tied to early Methodist spirituality confronted the realities of American political controversy, especially concerning slavery, the Methodist religious revolution faltered. The relationship between a powerful movement of spiritual renewal and the healing of American society was anything but simple.

Christianizing the New Nation

As has been often noted, the United States was transformed during the first decades of the nineteenth century by a far-reaching tide of Christianization, evangelical in its substance and voluntary in its form. To be sure, religious life in the early national period remained overwhelmingly Protestant, as it had been in the colonial era. (Catholics would not gain a significant presence until the burgeoning of German and especially Irish immigration in the 1830s and 1840s.) But the evangelicalism that spread rapidly in the early United States emphasized features that only a minority of earlier Protestants had stressed. Those features included a passionate focus on conversion, an all-out reliance on the Bible instead of tradition, and a demand that daily lives of ordinary believers display the virtuous fruits of conversion. Americans, in other words, were leaving behind European (and colonial) Christendom where religious allegiance had been mostly inherited. Instead, believers in the new nation had to adjust quickly to religious life without tax-supported funding for the churches; if Christianity was to endure, the faithful had to rely on their own initiative. Where there were no religious establishments, believers had to convince their fellow citizens to choose a life of faith. Because the nation’s founders were convinced that church establishments corrupted public life, they instituted a national principle of religious free exercise, which the states also gradually accepted. As this distinctly American experiment unfolded, Methodists led the way in demonstrating that self-generated religious fervour and self-directed voluntary organization could overcome the loss of establishmentarian privilege and fuel religious life of extraordinary dynamism.

The relationship between a powerful movement of spiritual renewal and the healing of American society was anything but simple.

To indicate the scale of religious transformation, consider that in an era of explosive population growth, church adherence grew much faster. Between 1776 and 1850, the number of Americans actively associated with the nation’s churches rose from about one-sixth of the population to over one-third. During this same period the number of Christian ministers increased three times more rapidly than the nation’s rapidly rising general population. Richard Carwardine, author of Evangelicals and Politics in Antebellum America, the best book on its subject, has written that by the mid-1850s, 40 percent of the population was “in close sympathy with evangelical Christianity. . . . This was the largest, and most formidable, subculture in American society.”

That percentage is most impressive when considered in context. The only thing that came anywhere close to the organized reach of the evangelical churches was the beginnings of a national economy involving both North and South in the business of slavery, but not yet thoroughly interconnected until the later coming of the railroads. No other system of value connected the disparate regions of the country. No other movement, political or otherwise, generated anything like the vast quantity of evangelical print: the American Bible Society (founded 1816) pioneered both industrial-level production and a national system for book distribution; until the appearance of the “penny press” in the 1830s, Protestant periodicals were the only communications medium distributed nationwide.

In addition, nothing came even close to the Scriptures in supplying a common fund of tropes, images, and moral imperatives. Think of Abraham Lincoln, himself not a church member, but yet a master of biblical imagery (“a house divided against itself cannot stand”), biblically inflected prose (“four score and seven years ago”), and biblical wisdom (“If God wills that [the scourge of war] continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said ‘the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether’”). Think also of Lincoln called “Pharaoh” and “Judas” by Confederates and, after the Emancipation Proclamation, “Moses” by the nation’s black population.

The Methodist Age

Methodists were, of course, not alone in propelling the decades-long process of Christianization. Yet it is erroneous to think of an undifferentiated evangelical Protestantism as the crucial agent of change. Winthrop Hudson, a great historian from an earlier generation, again provided telling comparisons to define what he called “the Methodist age in America.” He pointed out that by 1820, Methodists and Baptists, both relatively unimportant denominations before the 1790s, had each far outstripped all of the dominant colonial groups (Congregationalists, Presbyterians, Anglicans/Episcopalians, Dutch and German Reformed). By 1840, the number of Methodists had grown to exceed the number of Baptists by a ratio of five to three. Remarkably, by that same year Methodist adherents outnumbered—also by a ratio of five to three—the combined membership of all of the main colonial churches. (The Catholic population in 1840, though growing fast, still lagged behind.) In 1860 over twenty thousand Methodist ministers were either itinerating or serving individual churches; the total of enlisted men and officers in the United States Army barely reached sixteen thousand.

Why did Methodists become such a powerful force? Above all was the innovative creativity with which they proclaimed standard Protestant convictions at a time of severe challenges to traditional Christianity. In The Age of Reason, published in 1794 and 1795, Tom Paine mocked the Bible and denounced orthodox Christian theology—and that work sold more widely than his memorable tract from 1776, Common Sense, which had convinced the colonists to throw over the monarchy of George III. Americans panicked by the French Revolution that unrolled from 1789 and the Rebellion of the United Irishmen that followed soon thereafter (1798) believed revolutionary nihilism was invading the new United States. Many, and not just slave owners, were convinced that the bloody slave revolt in Haiti that began in 1791 would soon spread to the United States.

Why did Methodists become such a powerful force? Above all was the innovative creativity with which they proclaimed standard Protestant convictions at a time of severe challenges to traditional Christianity.

After George Washington’s service as president ended in 1797, vicious conflict between Federalists (John Adams, Alexander Hamilton) and Democratic-Republicans (Thomas Jefferson, James Madison) threatened to tear the republic apart. In the run-up to the election of 1800, when Jefferson challenged the incumbent Adams, Congregational, Presbyterian, and Episcopal ministers in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia were joined by the presidents of Yale and Princeton in proclaiming that the “Bavarian Illuminati” were about to take over the country. Jefferson seemed the dupe of this conspiracy or its avatar. Meanwhile as Americans streamed out of the settled East to steal the land of Native Americans on the frontier, they seemed to be abandoning the time-honoured foundations of civilization (schools, respect for property and the rule of law, churches).

To settled regions and the opening West in this tumultuous hour came travelling Methodist preachers who paid almost no heed to the French, Federalists, Jeffersonians, the Illuminati, or Tom Paine. Instead, with singleness of purpose, they concentrated on saving souls and encouraging converts to live holy lives.

Their message reiterated a standard Protestant appeal—sinners needed to be redeemed by God’s grace—but with compelling new emphases. As the Minutes from their organizing conference in 1784 put it: “What may we reasonably believe to be God’s Design in raising up preachers called Methodists? To reform the Continent, and to spread scriptural holiness over these Lands.” What did they mean by reform? To repeat: holiness in action, drawn from “the Bible alone,” and demonstrated practically in daily life.

But instead of relying on ministers “settled” as pastors of individual congregations, Methodists recruited young men who were willing to travel assigned circuits, often in brutally harsh conditions. Their mandate was simple: preach for conversion and encourage the local “classes” of laywomen and men who met regularly to encourage each other in holiness.

Like the Baptists, who were almost as effective in preaching simply, directly, and in the language of ordinary people, the itinerants based what they had to say on the Bible. Ministers of the more traditional denominations also grounded their preaching in the Scriptures, but they also expected deference to their status as educated leaders, they worried about unlearned upstarts upsetting social order, and they took for granted material support from settled communities.

The older denominations eventually did adjust to the free-for-all created by American democracy, but it took time. By contrast, the Baptists exploited it immediately. Methodists exploited and organized it both.

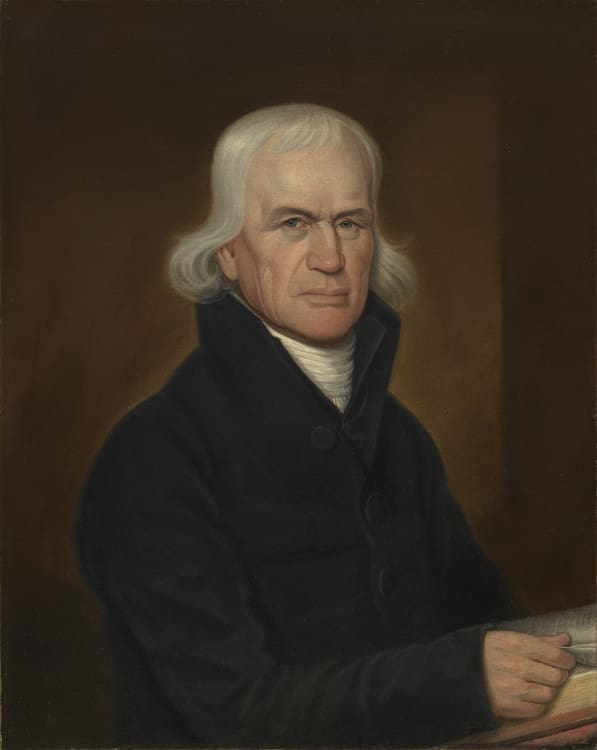

Francis Asbury in the Lead

Leadership was always crucial in making Methodists the marvel of the age, and no leader played a more important role than Francis Asbury. He had been an apprentice blacksmith in Birmingham, England, when as a sixteen-year-old he experienced conversion under lay preachers associated with John Wesley, the father of Methodism. Soon Asbury himself became an exhorter and then a circuit-travelling preacher. In 1771 at the age of twenty-six he responded to Wesley’s appeal for workers to assist the handful of Methodists in the American colonies.

The accumulated totals are staggering: 300,000 miles travelled, mostly on horseback; traversing the Appalachian Mountains more than sixty times; 16,000 sermons preached; more than 4,000 itinerants ordained; organizing 224 annual conferences of state Methodist conventions.

Indefatigability defined the rest of Asbury’s life. Until his death in 1816 he travelled constantly, except during the Revolutionary War when forced to lie low because of Wesley’s well-known opposition to American independence. From the early 1780s Asbury made an annual journey throughout the entire United States (and into Canada) to preach, recruit fellow itinerants, encourage adherents gathered in the “classes,” restrain untoward enthusiasm, and cauterize moral lapses, of which there were only a few. The accumulated totals are staggering: 300,000 miles travelled, mostly on horseback; traversing the Appalachian Mountains more than sixty times; 16,000 sermons preached; more than 4,000 itinerants ordained; organizing 224 annual conferences of state Methodist conventions. Without rival, Asbury was certainly the single individual known personally by more Americans than any of his contemporaries (and probably also English-speaking Canadians). Leaders who joined and then followed Asbury sustained nearly the same level of zealous dedication for over a generation after his death.

Under Asbury’s leadership, tiered layers of Methodist organization worked powerfully to encourage (and guide) the lay-led local classes, recruit (and assign) itinerants and settled ministers, inspire (and coordinate) the movement. Local classes sustained believers young and old, white and black, rural and urban, Americans and Canadians. Regional and state-wide meetings collected detailed records that counted class members “in society” and monitored the meager compensation received by itinerants. Every four years a General Conference convened for inspiration, encouragement, coordination, and the resolution of conflicts.

Asbury was not a deep theologian like Jonathan Edwards or a particularly riveting speaker like the earlier George Whitefield or the later Charles Grandison Finney. Instead, he became an even more effective instrument of John Wesley’s vision for spiritual renewal than Wesley was himself in Britain: dedicated to a message of divine grace (adjusted from Calvinism with more room for human response); committed to taking the message out to the people wherever they lived; eager to recruit any individual of whatever social or educational background willing to serve (men for the itinerancy, but women as keys to sustaining local Methodist life); and, above all, single-minded devotion to the cause.

Contentious Protestants

In a word, Methodists guided by Asbury revived, reformed, and renewed American religion. Yet inevitably this “awakening” concentrated so intently on matters of the spirit worked an effect on American society. To grasp the conflicted character of that effect, however, it is necessary to compare the Methodists with their peers.

Other American Protestants not already so inclined came gradually to imitate the Methodists: less concern about formal training, more time given to singing, preaching geared to conversion, and a focus on practical exhortation. As they also adjusted to the free forms of the new nation, they too contributed significantly to national Christianization. But unlike the Methodists, most other Protestants shaded their religious efforts with political commitments.

On one side stood sectarian or libertarian believers, with Baptists in the lead, but soon joined by the followers of Alexander Campbell and Barton Stone (Disciples of Christ, Churches of Christ, Christian Churches) and many independent “Christians” who were making the most of new possibilities in a democratic society.

Politically, libertarian Protestants railed against all forms of national organization as leading back toward the top-down tyranny from which the nation had recently escaped. Many of them actively supported Thomas Jefferson and his ideal of a citizenry composed of self-governing yeoman. Later, they became a key constituency in Andrew Jackson’s Democratic Party. Consistently, they assailed the plans for national reform from Federalists and then Whigs as covert strategies to undermine “the liberty wherewith Christ hath made us free.”

Against them stood the nationally minded Protestants, first as the Federalist Party at prayer and then consistent supporters of the Whig Party. In contrast to Baptists and “Christians,” leading Congregationalists, Presbyterians, Episcopalians, and Unitarians wanted to create national organizations to encourage the public virtue without which the republic would fail. These proprietary or custodial Protestants were responsible for the great voluntary agencies that laid the foundations for a truly national civilization, like the Bible Society as well as the American Sunday School Union (1817) and the American Tract Society (1825). The same constituencies led in creating tax-supported public schools where daily readings from the King James Bible would mold virtuous citizens.

Methodist distinctives and the new nation’s ideology developed on unconnected, but parallel, lines.

Unlike both libertarian/sectarian and custodial/propriety Protestants, Methodists were different. Francis Asbury did not mind if lay Methodists took up civic duties, like Richard Basset (a Federalist) who served as a Delaware governor or Edward Tiffin (a Jeffersonian Democratic-Republican), the first governor of Ohio. But he insisted that the movement as a whole remain firmly fixed on its specifically religious purposes.

At least as long as Asbury lived, Methodist bishops, itinerants, and most local classes sidelined concerns about the nation as such. It took the War of 1812, for example, to distinguish American Methodists from their Canadian counterparts. Earlier, itinerants, regional conferences, Asbury’s travels, and Methodist publishing had simply disregarded the border. The historian Dee Andrews has offered a compelling explanation for why Methodists could remain so oblivious to politics while at the same time achieving such success in a nation consumed by political passions. “Both Methodism and the new emerging democratic republic were eighteenth-century products of disassociation from organic community, familial hierarchy, classical tradition, and the church state connection.” As such, Methodist distinctives and the new nation’s ideology developed on unconnected, but parallel, lines: “a democratic ethos that foreswore allegiance to social or religious elites and was dedicated to the popular voice; a potent revivalism that in its most effective form equalized, even dissolved, if temporarily, the racial, gender, and social differences that republican rhetoric, in its most visionary form, lent credence to; and a sometimes blunt indifference to intellectual and academic tradition.”

But What About the Renewal of Society?

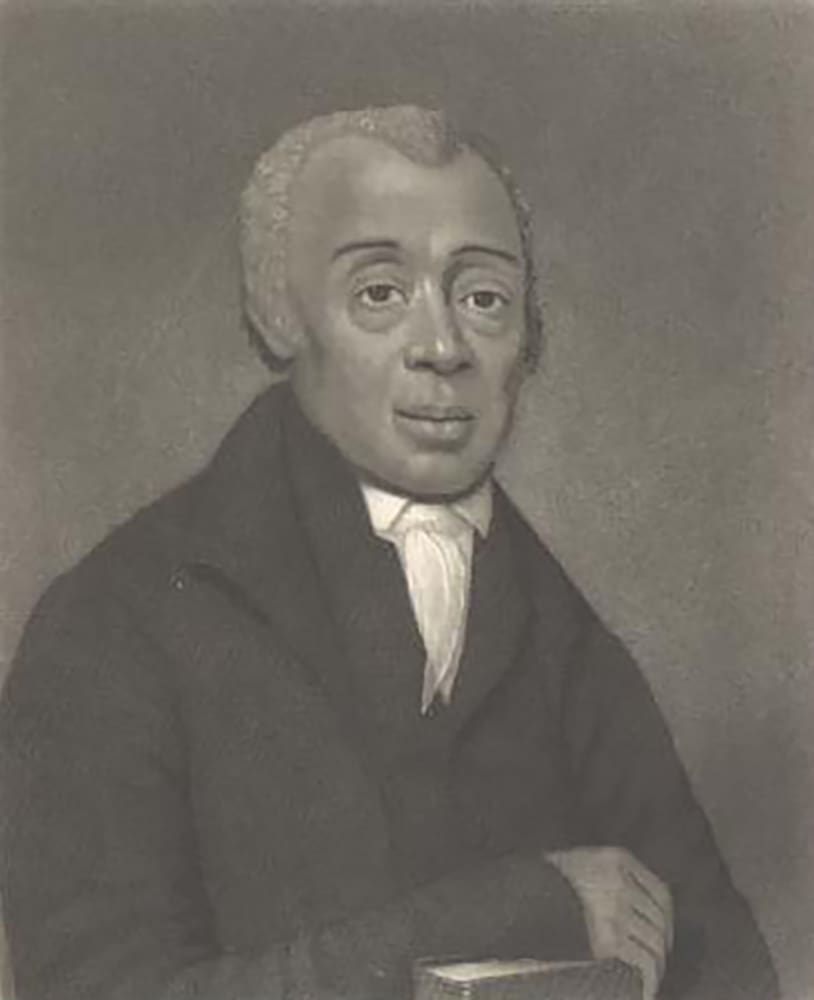

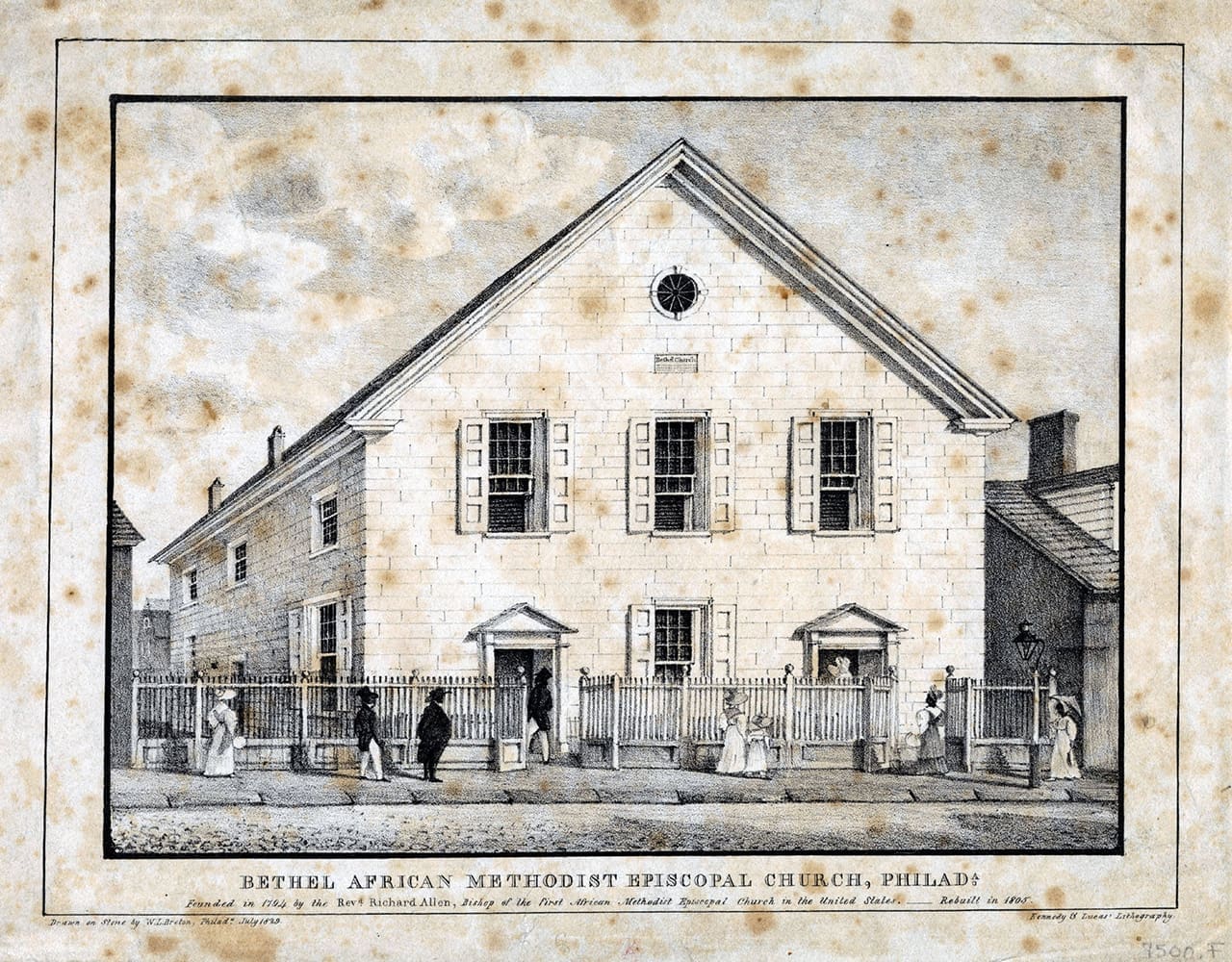

If the Methodists deliberately turned away from anything political, their revolutionary religious reform nonetheless affected the general public. Most notable from a modern perspective was Methodist success in evangelizing black Americans along with whites. Their detailed records reveal an achievement in interracial organization unique for the times and rare in later American history. In 1813, three years before Asbury’s death, African Americans accounted for 20 percent of the Methodists “in full society” (48,850 out of 214,298) at a time when the national black population stood at 18 percent. To be sure, some of the local classes, especially in the South, were segregated—but many were not. Unlike almost any other American movement of any kind, Methodists also gave some blacks public visibility as local exhorters. For one period of several years Asbury himself travelled with Henry Hosier, a pre-literate African American whom Asbury encouraged to preach because Hosier was so effective in expounding the texts he memorized.

During the same period, Richard Allen and his associates organized Bethel Church as a local congregation in Philadelphia and then the African Methodist Episcopal Church as a denomination serving black Americans. Allen had to overcome much white opposition to establish the AME, but he received at least some assistance from Asbury and a few other white Methodists. Despite conflicts that could have soured him on the tradition, Allen repeatedly reaffirmed his loyalty to Methodism. As he wrote late in life, “The Methodists were the first people that brought glad tidings to the colored people. I feel thankful that ever I heard a Methodist preach . . . for all other denominations preached so high-flown that we were not able to comprehend their doctrines.” What Allen sought, Methodism provided: “I was confident that there was no religious sect or denomination would suit the capacity of the colored people as well as the Methodist; . . . the reason that the Methodist is so successful in the awakening and conversion of the colored people [is] the plain doctrine and having a good discipline.”

By comparison with other contemporary American institutions, early Methodism’s all-out devotion to “scriptural holiness” opened a space for African American self-determination that would not reappear for a very long time.

Assuredly, black Methodists did not escape the prevailing racism of the era. Yet by comparison with other contemporary American institutions, early Methodism’s all-out devotion to “scriptural holiness” opened a space for African American self-determination that would not reappear for a very long time.

And the Methodist social impact went further, especially by nurturing the dedication characterizing lay Methodists who gathered in class meetings to confess their faults “one to another” and receive encouragement for living honourably day after day. A prime social example was the movement’s stand against alcohol. For generations to come Methodists would be mocked as prissy teetotallers, but in a United States overrun with alcohol-fuelled dissipation, their abstinence stood out in vivid contrast. It even won the favourable notice of many who did not share their faith. (Abraham Lincoln kept clear of the Methodists’ religion but aligned with them as one such teetotaller.) In general terms, Methodist piety generated the kind of self-discipline desperately needed in a nation that had thrown over traditional European supports for social order.

Complexity from Exalting “the Bible Alone”

The difficulty in moving from spiritual renewal to social transformation was shown most clearly by the Methodist success in appealing to “the Bible alone.” Especially as other denominations imitated the Methodists in all-out reliance on Scripture, public use of the Bible generated more conflict than harmony.

During the colonial and Revolutionary periods the Bible had been ever-present in public life, but mostly as rhetorical support for the Protestant British empire (versus Catholic France) and then as a fund of exemplars during the War for Independence (Israel led by “Moses” a.k.a. George Washington, escaping the tyranny of “Pharaoh” a.k.a. George III and the British Parliament). It was reasoning not from Scripture but with Scripture in hand when colonists called France’s Native allies “Canaanites,” or when Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson proposed an image of the pillar of cloud that guided the children of Israel in the wilderness as the seal of the new United States.

In the early republic and following the Methodists, all Americans broadened their appeals to the Bible. But unlike the Methodists, others instinctively carried “the Bible alone” out of piety into politics. When the public use of Scripture moved from rhetoric to policy, the Bible fuelled contentions that distinguished American Protestants from their fellows in Britain.

The obvious example concerned the morality of slavery. In the last decades of the eighteenth century, Quakers and a few Unitarians joined evangelicals like William Wilberforce in leading Britain’s attack on the slave trade. Although Wilberforce was as devoted to Scripture as his evangelical contemporaries in America, he addressed Parliament with a focus on trade and general morality instead of appeals to the Bible.

In sharp American contrast, as soon as the new legislature of the United States took up questions concerning slavery in the 1790s, congressmen and senators were hurling biblical texts at each other in order to defend their pro- or anti- positions. During the first decades of the new century, more and more of the spokesmen who addressed the public on this issue appealed directly to scriptural warrants. After heated debate leading to the Missouri Compromise in 1820, widespread publicity in 1822 for the Denmark Vesey conspiracy in Charleston, and even more attention to Nat Turner’s rebellion in 1832, biblical argumentation poured from the presses and featured prominently in many public forums.

Fervent biblical appeals defended American slavery, attacked American slavery, and laboriously explained why the institution might be evil (or beneficent) but not directly (or directly enough) addressed in Scripture. Abolitionists cited Old Testament legislation establishing a Year of Jubilee, the golden rule from Jesus’s teaching, and the apostle Paul’s declaration that in Christ there was neither slave nor free. The response? Moses had allowed the ancient Hebrews to perpetually enslave “the heathen that are round about you” (Leviticus 25:44), Jesus demanded many reforms but never mentioned enslavement, and the apostle Paul urged slaves to obey their masters “in the Lord.”

These contentions, along with similar appeals to Scripture concerning Sunday mail service, Cherokee removal, public education, and especially temperance, made Scripture more salient in public disputes than anywhere else in the world. Although other Protestants pitched in, Methodists had led the entire country in looking so unreservedly to the Bible.

A Hard Road from the Spiritual to the Social

In a society cut loose from the recognized guideposts of the past and everywhere imperilled by democratic excess, Methodist concentration on “scriptural holiness” produced remarkable results, particularly in joyful personal liberation, disciplined personal piety, and supportive community fellowship. Yet the singleness of purpose that kept Methodists from instrumentalizing their religion for political purposes was shaping a society where others did not hesitate.

Observers in the early twenty-first century where the politicization of religion has become so contentious might consider an ability to remain above the fray idyllic. Simply by not harnessing their religious energies to political bandwagons, early Methodists did maintain their religious integrity. Yet with a political tabula rasa, the Methodist movement could not offer much resistance to other influences once Asbury’s iron discipline passed from the scene. Because Methodists had not developed mechanisms for connecting individual piety to systemic public responsibilities, they drifted like political chameleons after Asbury’s determined apoliticism wore off.

It took time for that apoliciticsm to fade, but as the movement became more respectable and more preachers transitioned from itineration to settled pastorates, Methodists drew closer to their Protestant peers. When they first engaged the political sphere, Methodists were drawn to the Whigs because of the Whigs’ anti-Catholicism. Later, after the denomination divided in 1844 over whether to allow a slaveholder to serve as a bishop, Northern Methodists became strongly Whig, and then Republican. In the South they took on the colouring of the dominant political class and became reliable Democrats. As had earlier happened when Methodist division at the Canadian border led to controversy over the Methodist Book Concern, bitter controversy blazed after 1844 over controlling the denomination’s publishing assets. When all-out concentration on piety cooled, Methodists found themselves trapped in political conflict as thoroughly as their peers.

The Methodists’ well-documented record on slavery shows the difficulty in spiritual renewal leading to social transformation. At their founding conference at Christmas in 1784, the new denomination boldly announced its opposition to chattel bondage: “We view it as contrary to the Golden Law of God on which hang all the Law and the Prophets, and the unalienable Rights of Mankind, as well as every Principle of the Revolution, to hold in the deepest Debasement, in a more abject Slavery than is perhaps to be found in any Part of the World except America, so many Souls that are capable of the Image of God.”

Yet as the enthusiasm for “liberty” from the war era faded and as Methodists made spectacular gains in slaveholding regions, the earlier certainty that slavery contradicted “the Golden Law of God on which hang all the Law and the Prophets” also faded. Methodist consciences certainly remained troubled. But conversions based on biblical preaching and holiness pursued along biblical guidelines could not by themselves sustain the denomination’s earlier biblical protest against bondage.

Success in “Methodizing” American religion on the basis of scriptural imperatives operated on one plane. The earlier conviction that the Bible did not allow slavery operated on another.

In this progression, the history of Methodism spoke for the history of American Protestantism writ large. Success in “Methodizing” American religion on the basis of scriptural imperatives operated on one plane. The earlier conviction that the Bible did not allow slavery operated on another. Popularizing Methodist conceptions of biblical conversion and scriptural holiness was not the same as giving Methodist interpretations of Scripture special authority in addressing slavery.

In more general terms, nearly universal Protestant agreement affirming the authority of the Bible, along with significant agreement on what it meant personally to follow Christ, did not translate into a common understanding of social order or common approaches to political decision-making. Instead, deeply ingrained assumptions derived from neither personal piety nor biblical teaching—especially about race, but also the market, personal ability, and the glories of liberty—exerted a powerful sway. Fervent commitment to “the Bible alone” and passionate concentration on the standing of individuals before God did result in many Americans undertaking public activity with Scripture in hand. Fervour and passion did not, however, guarantee anything like the commonality on narrowly religious matters the Methodists had done so much to create.

The Methodists’ single-minded religious commitment remains an underappreciated marvel. Their reliance on “the Bible alone” reaped an extensive harvest, including a much greater public respect for Scripture. As a religious force, it is only a slight exaggeration to say that all America became Methodist. Yet given the centrality of Protestantism in the emerging American civilization, Methodism also became a social force whether Methodists desired that outcome or not. It was a social force, however, at the mercy of conflicting political interests.

During the recent Asbury revival, one of the student leaders was asked whether it meant greater support for the Republicans or the Democrats. She replied, “Jesus does not do politics.” This perceptive young woman clearly saw that to assess a religious event primarily for its political impact was to betray its spiritual integrity and almost certainly to undercut its spiritual effect.

In earlier American history, because the Methodists succeeded in keeping their Christian message nonpartisan, they brought spiritual hope to a huge spectrum of individuals and groups. At the same time, the marvel of early American Methodism resulted in a renewal of American society that could not be sustained when spiritual brothers and sisters followed their conflicting certainties about scriptural truth into acrimony, disunion, and the bloodshed of civil war. For the many in our day who hope for spiritual transformation and the renewal of American society, the lesson from early Methodist history is sobering. It is almost certainly incorrect to think that Jesus does not do politics, at least in some fashion, but it remains as difficult as it is imperative for those eagerly seeking both goals to ask, what would Jesus do?