Two thirteen-year-old boys are taken from their families and given away to unknown strangers: strangers with unclear motivations, who don’t speak a single word of their language, whose characters are entirely unknown.

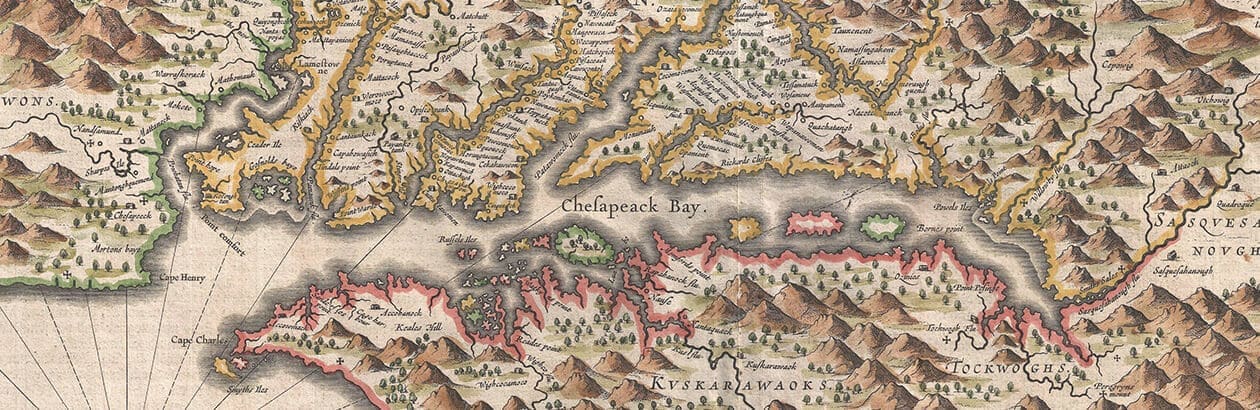

It could be the premise of a recent thriller or an edgy literary novel. But the year was 1608, the place was Jamestown, and the English captain Christopher Newport was gifting young Thomas Savage, newly arrived from England, to the Pamunkey chief Wahunseneca (the “Powhatan” of the First Nations tribe living near the infant colony). In return, the Powhatan bequeathed the adolescent Namontack to the English aliens. The two children immediately became pawns, played by adult gamers for their own advantage: hostages to ensure good behaviour, living gestures of good faith, translators, double agents.

This is the starting place for Pocahontas and the English Boys: Caught Between Cultures in Early Virginia, a sequel of sorts to Karen Ordahl Kupperman’s well-received The Jamestown Project (2007). The earlier book is a detailed, vivid examination of Jamestown’s origins (in Kupperman’s own words, a “creation story from hell”); Kupperman’s new study homes in on a single aspect of the colony’s foundation: the exchange of teenagers between the two peoples.

In the early years of the colony, numerous English boys were sent—their consent wasn’t deemed necessary—to live with the Native Americans nearby. The Jamestown Project treats this briefly, as one survival strategy among many. “The English boys,” Kupperman wrote then, “helped keep the lines of communication open and, despite all its problems, the colony held on.”

In Pocahontas and the English Boys, this exchange of young people takes centre stage, and Kupperman’s focus narrows in from Jamestown as an entity to the youths who were expected to adopt a new culture while still holding on to the old. Pocahontas, a regular visitor to the English colony, is essentially a framing device, a familiar name to draw the reader in; although she does move from her own world into another (where she marries an Englishman and then dies, leaving an infant son), she is not in the same position as the English boys. These very young men were powerless, without status, without family, without resource. And because they were, in Kupperman’s words, “not yet fully formed . . . flexible and full of possibilities,” they were forced to adopt fluid identities, constantly adjusting their appearance, manners, and personalities in order to survive.

“A surprising number of boys and girls were forced to live in multiple cultures . . . in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries,” Kupperman writes, and her narrative touches briefly on a number of them (not all of English origin), but her focus is on just three: Thomas Savage, whom Christopher Newport misrepresented to the Powhatan as his own son; fourteen-year-old Henry Spelman, given to the Powhatan’s son by John Smith in 1609; and Robert Poole, age uncertain, handed over to Opechancanough, a kinsman of the Powhatan, in 1614. To a lesser degree, she also chronicles the experiences of Namontack, and of another English “page,” Samuel Collier, casually given away by John Smith to the Weraskoyack tribe “to learn the language.” All of them grew into adulthood in an odd, uncomfortable limbo, suspended between two cultures that were constantly teetering on the edge of war.

This between-worlds adolescence turned the English boys into something different: neither Indian nor English. They were expected to submerge themselves in the native languages and customs while still remaining “wholly English and completely committed to the English way of thinking.” But, as Kupperman adds, “that is not how it worked.” As they absorbed the native ways, dressed in native clothes, and developed a taste for native foods, the boys found their loyalties shifting.

At the same time, they remained outsiders to the First Nations; the chiefs to whom they’d been given were both their adopted fathers and their captors. When young Henry Spelman dared to refuse an order given by the chief’s wife, he was beaten so badly that he could barely walk. He dragged himself to a neighbour’s house and hid in terror, but later that night the chief himself appeared, carrying his youngest child, and begged Henry to comfort the weeping toddler. The little boy missed his older “brother” and was inconsolable until Henry came “home.”

Pocahontas and the English Boys is an engaging read, one that challenges the conventional history-class understanding of colonial America, where Indians and whites face each other across clearly drawn lines. Kupperman salts her study with examples of Europeans who slip completely into Native American cultures and stay there, further complicating the traditional narrative; somewhat less successfully, she provides a brief look at young First Nations transplants into the Old World.

Kupperman beautifully portrays the liminality of the English boys, the fate of those who no longer belong fully to their own culture yet never completely enter another: “Because these young men with fluid identities controlled the relationship between the English colonists and their most powerful friends/enemies,” she concludes, “and because they understood the feelings and culture of both sides, they were always seen as potential betrayers.”

But the book falters slightly in its conclusion. The final chapter tries to connect this story to a larger historical lesson, skipping from Pocahontas and the English boys to the prevalence of double agents in European politics, then to the “thousands” of Englishman “captured by North Africans . . . who then converted to Islam or, in the language of the day, ‘turned Turk,’” then to the English suspicion of “secret Roman Catholics” (possibly even Jesuits disguised as Jews); then, with a single-sentence segue (“Seventeenth-century fears about ambiguous identities and hidden motives evoke modern examples”), leaps forward to the Japanese internment camps of 1940s America, the American reaction to POWs who assimilated to the culture of their captors during the Korean War, and the 1970s rise of the concept of Stockholm Syndrome.

It doesn’t work; this is all done too sketchily, with far too much empty space between the connected dots. And as I turned the final page (in some discontent), I realized that I had an unanswered question. What happened to Thomas, Henry, and Robert? What about Samuel and Namontack? Kupperman had brought them into young adulthood, but somehow I’d missed the end of their stories.

A hunt back through the pages revealed that apart from Pocahontas (whose death at twenty-one, in London, gets a page and a half) the dramatis personae had exited the stage practically without notice:

English leaders saw youths as more expendable than full-grown men were. Smith casually mentioned that he had left his “page” Samuel Collier with the Weraskoyakcs to “learn the language” in 1608. The records never referred to Samuel again until Smith recorded his death in the early 1620s.

A look at The Jamestown Project reveals that Samuel died “by accidental discharge of a gun,” probably in 1622. He was, in all likelihood, twenty-nine or thirty at the time. We don’t know whose hands held the gun.

Namontack, who plays a more important bit part in Pocahontas and the English Boys, simply disappears from the story, although an endnote in The Jamestown Project remarks that an unreliable report suggests he might have been murdered in Bermuda (which could actually refer to the Virginia plantation known as the Bermuda Hundred).

Thomas Savage became an independent landowner, married an English émigré named Hannah in his twenty-sixth year, and sired a son; mid-paragraph, Kupperman reports his death, in his early thirties, “sometime between 1632 and 1633,” leaving Hannah as a wealthy widow: cause unknown, his end and resting place left undescribed.

Robert Poole eventually became a landowner and trader. Kupperman tells us nothing more, either here or in The Jamestown Project.

In his twenty-eighth year, Henry Spelman was accompanying an English trading party along the Potomac when the tribe he had once lived with attacked the party unexpectedly and “all the English were killed or taken prisoner”—presumably including Henry, although Kupperman never mentions his name. Even though he plays such a large part in Pocahontas and the English Boys, Spelman actually gets a slightly more detailed death scene in The Jamestown Project than he does here; another colonist remarks that this end was no more than Spelman deserved, but nevertheless his death was “a great loss to us for that Cap. was the best linguist of the Indian Tongue of this country.” With his murder, Jamestown had lost an important asset.

And it is this, not the dilemma of being stranded between cultures, that stands out in the stories of Thomas Savage, Robert Poole, Henry Spelman, and the rest. These children were on ships to the New World, separated from their families, because they were human capital. They were disposable assets that could help populate the English towns in the New World, and if they died, no great matter; there were more where those came from. (“Most of the boys on the ships quickly disappeared from the records,” Kupperman remarks, in the introduction.) The population of England, and particularly London, was on an upswing. There were too many young indigent mouths in London, and the project of colonization required not merely multiple attempts but the deaths of thousands of “surplus” people, expendable in the relentless quest to occupy the new lands. Women were rarely sent to brand-new colonies—not because they were delicate and needed protection, but because they were too valuable to “waste.” The strategy of colonizing nations was, instead, to send poor young men. Violent, unproductive, and troublesome, they became colony fodder. The women arrived only once survival was a real possibility.

And without a constant supply of young men, colonies could not survive. Look back two centuries: of the twenty-five hundred colonists who arrived with Nicolas de Ovando in Hispaniola in 1502, one thousand died within months; this pattern was repeated over and over again. The “Lost Colony” founded in the new Virginia territory may be surrounded by mystery, but its fate was no different from that of a score of others: a colony had to be resupplied with human souls again and again before it could survive.

Kupperman actually ambles across this territory late in the book, but she never connects it to Thomas, Robert, and Henry, merely treating it as a stage of colonial growth:

The Virginia Company encouraged the City of London to send a hundred children “of twelve years and upward” annually to help populate the colony. These children were to be assembled out of the “multitudes that swarm” in the streets of London. When the company learned that some of the proposed deportees were . . . reluctant to go, it asked for authority to force them onto the ships, and the king’s Privy Council was happy to grant the company the right to ship them off against their will. . . . The poet John Donne, who was the dean of St. Paul’s, preached a sermon before the Virginia Company praising the policy of forcing poor children to go to America. He . . . said the project “shall sweep your streets and wash your doors, of idle persons, and the children of idle persons, and employ them.” Drawing on the medical lore of the day, he pictured Virginia as a spleen to drain England’s foul humors and a liver to breed good blood.

Of course these children were casually handed off to unknown strangers; of course scores of them disappeared from the historical record; and of course Kupperman doesn’t need to round out their human stories by chronicling the end of their earthly existence. Their individual fates are of little importance. Once she’s explored the fluidity of their identities as young men, they have served their purpose. In a genteel, academic, relatively harmless, and undoubtedly unintended fashion, she’s following in the Virginia Company’s footsteps.

If there’s a larger historical lesson in Pocahontas and the English Boys, perhaps it’s less about fluid identity, suspicion, and betrayal and more about the ways in which we think, and speak, of the “surplus population”: the poor, the unemployed, the resourceless, the exiles and migrants.

The English boys are continually referred to as commodities, advantages, assets, investments. These are terms of value, yes, but they have to do only with the usefulness of a person to a cause; they obscure the humanity of a soul struggling through life on this earth. When we speak of a human soul as an asset to the US economy, or a drain on our resources, or when we rate those at the border as worthy or unworthy based on what they might contribute to us, we are following in the Virginia Company’s footsteps: using the terms of value and wealth, prosperity and benefit, to describe the existence of a transcendent being made in the image of God.