W

When the telegraph was first invented, the Baltimore Sun declared that “time and space have been totally annihilated.” This meant that communication no longer travelled at the speed of man, and that instant connection between disparate parts of the globe made time and distance a much less significant factor in human affairs.

This had wonderful consequences. The inventor of the telegraph, Samuel Morse, created the instrument because a too-slow letter had kept him from being at his wife’s bedside before she died. At the same time, the elimination of time and distance has drawbacks. Henry David Thoreau bemoaned the fact that the world’s tragedies and gossip began to fill our minds with distant chatter every morning in the news. This threatens to distract us, he thought, from the challenges, beauties, and relationships that are right in front of us.

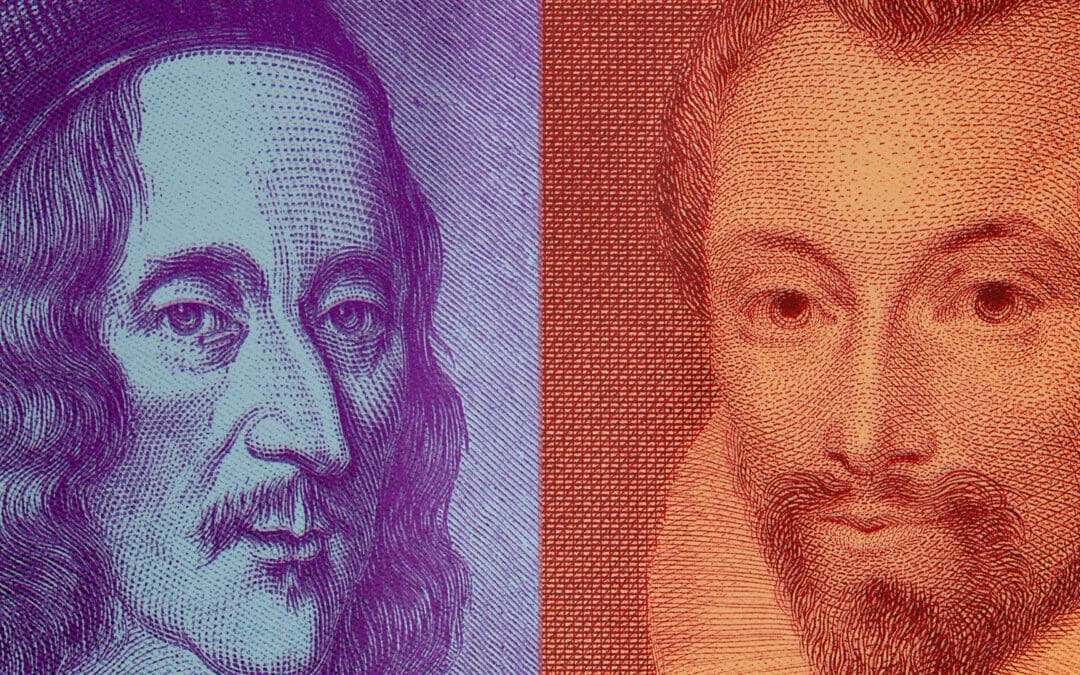

Neil Postman, the famous media scholar, held it as a principle that all technological advances were trade-offs: their benefits always come with a corresponding disadvantage. “The printing press annihilated the oral tradition; telegraphy annihilated space; television has humiliated the word,” he said, and, prophetically, concluded: “the computer, perhaps, will degrade community life.” What did Postman mean? Hasn’t the internet helped us form communities? Many have found the company of the like-minded online when none could be found near at hand, others have found fan communities of those with shared interests, and the web has allowed the organizing of political activism and protest too.

Still, something important has changed about the way we think about community in the internet age. A word that once referred to a group of people sharing life together in a particular place has come to refer, today, to abstract categories. Where once we might have spoken of the community of the South Bronx or the community of Parma, Ohio, we now talk about everything from the fishing community to the gaming community to the disability rights community, abstract groups that may not share life or know one another at all. This is not just a minor linguistic development; it means that the idea of community has been lifted out of the context of concrete relationships, and the consequences of this change are significant for our public life.

Because the word “community” has come to mean so many different things, it may be helpful to propose a framework for thinking about its various meanings. In getting clear about this, I think, we have a better chance of approaching the challenges of loneliness, depression, and despair that have afflicted us since local communities began to be replaced by the abstract communities made possible by digital technology.

Categories of Interest Versus Communities of Care

It’s clear that local community has been replaced in many instances by interaction through screens. Robert Putnam and sociologists like him have ably charted the decline of in-person association since the middle of the last century and the symmetrical growth of time that Americans spend each day in front of a screen. This change has significantly reshaped our use of the concept of community.

First, in the world of politics and business, the word “community” has come to refer to interest categories identified by professionals with needs for classifying constituents and customers. These interest groups may be professional, ethnic, social, age-based, or class-based, and may be multiplied to include any sort of categorization that labels a collection of people with shared needs or aims. Thus you might hear of the legal community, the elderly community, the sports community, or the working-class community. These groups are distinguished chiefly by a shared material interest and secondarily by having been labelled in a top-down fashion rather than growing up organically.

Like all of the new, contemporary uses of the word “community,” this one is abstract rather than concrete. It does not refer to any particular group of people who really know one another, but rather to a category of persons who share some commonality that is important for politicians and policymakers. These abstractions are useful as a means of talking about who is being served or unserved by this or that policy. Gun control measures might be felt negatively by the hunting community but might serve the black and brown community or make the streets safer for the policing community. The word “community” is used here, perhaps, to add a humanizing touch to policy talk and political messaging. It sounds a bit nicer to say the “hunting community” rather than “hunters,” or “black and brown community” rather than “black and brown people.”

You might think that this also signals a trend toward thinking about people as part of a larger social framework rather than as individuals, but the reality of this language, I think, suggests otherwise. The communities referred to are not in fact the real communities we experience, but merely classes of people that have been labelled communities. These classes themselves name no group that is concretely real, but act as another attribute attached to a dispersed and unrelated set of individuals.

This notion of community can serve to disrupt solidarity locally, because it makes primary those parts of us that we may not hold in common with our neighbours.

It is worth thinking about where this language is used and who is using it. This is the vocabulary of politicians and corporations who are interested in marketing products and ideas and of thinking in terms of demographic categories. When we hear about the “elderly community,” we should also be alive to the fact that there is no meaningful difference between this term and the term “the sixty-plus demographic” as it might be used by a marketing researcher. This kind of talk, while useful in its place, takes account of us not as particular, unique people with our own dignity but as interchangeable members of a category whose usefulness belongs mostly to people and entities to whom we are statistics.

When we hear this language, we begin to think of ourselves in this way too, more by our interest labels than by our actual situation among the people around us. We feel more loyalty and commonality with other members of our abstract community than with someone on our street. In fact, we might feel more alienated from our literal neighbours, who do not share our interests, who might not be of our demographic, who might not have the same politics.

But these abstract categories are not communities of care. If I live in Sarasota, and I am a member of the “software engineering community” and there is another member of this category in Poughkeepsie, I am not going to get a casserole from Poughkeepsie when I’m laid up with a broken leg, and I’m not going to leave my son at his house when my daughter has a doctor appointment. Furthermore, since the unifying principle of these communities is shared individual interest, care is necessarily displaced as the core value.

Sometimes categories of interest and communities of care overlap; the line is not a clear one. You could have a shared interest with a fellow pipe fitter in your neighbourhood and also be a part of a community with that pipe fitter and others like you in the same town. But then you have transcended the category label that names you and have joined in some wider form of local, informal membership, to which those who do not share your particular interests might also belong.

At the same time, there are ways in which people support one another online. Stories of illness go viral and inspire many donations to GoFundMe, and this is the result of a good and generous impulse and ought to be admired. But this kind of thing also faces limitations as a form of genuine, sustained community and support, which must take place among a certain number of people who share place and life enough to support one another over time. If the psychologists are right, we can really nurture thick relationships with about 150 people, and the upper bound on a concrete community might be more like 1,500 before things get so large that we don’t know and recognize people.

Getting clarity about this distinction helps us do two things. First, it can help us recognize the needs we have for a diverse community of care among those who share our life. And second, it can reveal the absence of that community, which is concealed by the use of the term to refer to interest groups.

Categories of Taste Versus Communities of Moral Calling

Less politically salient, perhaps, but culturally of vast importance is the community of taste. Where categories of interest have as their key organizing factor a political or economic aim—a material interest—categories of taste are built on just that, aesthetic taste. What are often called “fan communities” are categories of taste, and so are categories like the hiking community, the sewing community, and the baking community.

Some of these categories of taste are sufficiently small so as to constitute a real community. For instance, aficionados of the Big Boy steam engine (the most powerful steam locomotive ever built) might be a small-enough group that the members of that category actually constitute a concrete and coherent web of relationships. The internet has helped these people find one another, and this can be a delightful thing. If I have never met a fellow enthusiast for the paintings of the Northern Song dynasty, the web might help me to locate a person with whom I can have wonderful conversations and who might even become a friend.

But these online categories of taste can lead in wayward directions. Because the algorithms of online life are designed to show us more of what we already like to see, the medium is prone to a process of unbalancing and radicalization. In its toothless form, this might take the shape of a fan community verbally abusing or making death threats at an actor or artist who dissatisfies their expectations about some commercial property to which they have attached with a too-passionate interest. In its more vicious forms, the process has led internet users to consume ever more violent, misogynistic, and disturbing forms of pornography, and has led many others into political radicalization and conspiracy theories.

Contrast these with communities of moral calling. Where a category of taste meets us where we are, for better or for worse, catering to what we happen to like for good or ill, a community of moral calling requires us to go beyond where we are. While a category of taste may or may not involve thick webs of relationship, a community of moral calling must do so.

These latter communities depend on shared life because moral development takes place within the fabric of daily activity and interaction. Consider the Rotary Club. Found in countless communities, large and small, all over the world, the Rotary Club aims to cultivate a spirit of service among its members. Its “Four-Way Test,” affirmed at the beginning of every meeting, serves as the organizing norm for all interactions, plans, and projects:

- Is it the TRUTH?

- Is it FAIR to all concerned?

- Will it build GOODWILL and BETTER FRIENDSHIPS?

- Will it be BENEFICIAL to all concerned?

These norms are embodied by the community and its members, who hold one another accountable to the mutually agreed-on virtues that constitute their shared life. In professional life, in recreation, in service, a Rotarian is expected to uphold these norms. They constitute a moral calling, not to meet us where we are, but to beckon us higher.

I’ve used the example of the Rotary Club here because it is a non-sectarian, highly influential example of a community of moral calling. Churches, fraternal organizations, synagogues, and many other local communities, however, are at the heart of this kind of shared ethical development. At a more basic level, families and informal relationships between friends constitute the fundamental stuff of our becoming good people. Each of these concentric communities of moral calling, when they’re working like they should, build off one another toward a sense of common endeavour toward the good.

This is not to say that local communities cannot become communities of moral corruption; that this is the case is so apparent that it needs no argument. But it is to say that the bias of digital media closes us in on ourselves and can keep us from moral progress by leading us deeper and deeper into what is wayward or unbalanced. The difference with a concrete community of moral calling is that it, at the very least, forces us out of our own individuality in order to learn how to reckon with others. At its best, it calls us to be better than we are.

Understanding this distinction helps us recognize that self-acceptance, self-worth, and the common good depend not on indulging our proclivities or tastes but on growing together with our neighbours into better people.

Categories of Identity Versus Communities of Place

“The next black community meeting is going to be wild,” Jane Coaston, a writer for the New York Times often jokes. She’s poking fun at the fact that reporters often refer to “the black community” as if it were one, single, homogeneous community. The joke points out something important about community and the way the word has changed. An actual community, it presumes, is something local and bounded enough that it could conceivably hold meetings. But communities of identity are by no means merely ethnic; they refer to any category you might classify as an “identity group.” These are distinct from categories of interest or taste in that they are focused not on what we want or what we like but on who we are.

These three communities clearly have some overlap. Who I take myself to be might have an influence on what I want and what I like, but they are nonetheless distinct. Not every Latino person will belong to the same categories of taste or interest, though they may belong to the same category of identity. I draw this distinction because identity, I want to argue, has a special relationship to solidarity. Who I take myself to be influences who I consider to belong to the same community of concern as I do.

Communities of identity have their use, perhaps, in creating a wide sense of social solidarity among those who share a certain characteristic, but they risk forming walls that cut us off from those with whom we might in fact share a neighbourhood. In focusing our sense of belonging on an abstract category of identity and encouraging us to locate our true self within that category, this notion of community can serve to disrupt solidarity locally, because it makes primary those parts of us that we may not hold in common with our neighbours.

The contrast to a category of identity is a community of place. Solidarity in this context is not a matter of clicks, likes, or words typed on a screen, but of the mutual support and shared burdens of daily life, throughout all of life. Solidarity of place means that we belong, not to a community that we have chosen because it is comfortable or because it is a category that makes us feel a part of something larger, but to a community we have been given with all its faults and complications. In a community of place we do not get to be a consumer; we do not get to opt out. Rather, our task is to care for those who are actually there in our lives, as the philosopher David McPherson has put it, whether we like it or not.

Like a community of moral calling, and indeed every form of community, a community of place has its corrupted and perverted manifestations. Recognizing this distinction, however, opens the path to more real forms of solidarity and relationship, because our own place is typically the one in which we have agency, knowledge, and power to effect change, and because within it we cannot take the self-centred attitude of the consumer. In this distinction between a community of place and a category of identity, we might wipe away distraction and confusion that keep us from being of service to our neighbours.

Violence, Men, and the Search for Significance

“All forms of violence are quests for identity. When you live out on the frontier, you have no identity. . . . You have to prove that you are somebody. . . . Ordinary people find the need for violence as they lose their identities. Terrorists, hijackers—these are people minus identities. They are determined to get coverage, to get noticed.” These words are from Marshall McLuhan, the renowned media scholar, told to a Canadian presenter on a 1977 television program. This quest for identity, he said, was not new, but at the speed of light (his phrase to describe the world of information technology) it was becoming more dangerous.

What I have described above is a process of alienation that has placed people who live in the most mundane of places into lonely and ideologically charged online frontiers. Having lost a social context that gave them an identity and a sense of place, they search for identity in the forms of zealous dedication to their own taste, excited attachment to identity categories discovered online, or activism in service of their interest group. But this quest for identity can turn into something more sour still, especially for young men.

McLuhan was not the first or last to identify the dangerous loss of identity for young men. Émile Durkheim, the French sociologist, coined the term “anomie” to describe the breakdown of moral standards in a social group. Psychologists who specialize in addressing radicalism and terrorism use the term “quest for significance” to identify those individuals most prone to online radicalization and to acting out in violence, whether these are Jihadis of the early 2000s or the nihilistic mass shooters of today.

For Durkheim, in the absence of something to aspire to and a moral framework in which to make progress, individuals give way to the insatiability of their own desires. Instead of asking themselves whether what they are doing is moral or approved of by the community, they instead seek to satisfy the open-ended and bottomless longing for individual satisfaction, and this manifests in all kinds of ways that are damaging to the broader society.

As the local community becomes emptied and with it the norms and bonds that direct desire in healthy ways, individuals are left adrift. Without local social structures and moral norms to guide them, they may engage in destructive efforts to achieve their own pleasures, or they may lash out in a desperate quest for meaning, significance, and acknowledgement.

Richard Reeves, a Brookings Institution expert, made waves over the last year with his book Of Boys and Men: Why the Modern Male Is Struggling, Why It Matters, and What to Do About It, which charts the shocking decline in the fortunes of American men since the 1970s. Men are significantly less likely than women to graduate from college and have increasingly adverse educational outcomes, they have fewer friends, their real wages are declining, and they make up more than three in four deaths of despair. The causes of these phenomena are complex, but they are creating miserable conditions for many men, especially for black men and men from disadvantaged backgrounds. At the same time, they accompany a general decline in community life that has left many young men alienated, depressed, and with a decreasing number of opportunities. As Neil Postman says, the disadvantages and advantages of new technologies are never distributed evenly across populations.

This environment of alienation is a perfect breeding ground for anomie and for the violence of identity to emerge. Last year I spoke with a pastor who works with gang members in Chicago’s south and west sides, and who described the way in which beefs begin today with disses on TikTok and Instagram and end with kids shooting each other. These are young men, he said, who are looking to be somebody, to be significant, to matter.

The internet is excellent at connecting people all over the globe to information, but the idea it contains is that community can be reduced to that exchange of information.

This specific violence is but one form of a larger problem. In its more innocent form, it may manifest as young men becoming keyboard warriors; in its more intense form, it may look like growing political radicalization; and in its most frightening form, it looks like the random acts of violence we see in school shootings or bombings.

McLuhan describes the way in which we search for identity in a world where television has supplanted community thus: “They become alienated from themselves very quickly, and then they seek all sorts of bizarre outlets to establish some kind of identity by ‘put-ons,’ and without the put-on, you’re a nobody, and so people are learning show business as an ordinary daily means of survival.” This show business takes place almost universally on social media sites, in chatrooms and forums, on Discord servers or Twitch streams. At their worst, put-ons can be backed up by damaging, real-life behaviour.

The replacement of community life with abstract digital life sees its most striking manifestation here, where it may become a matter of life and death. Without healthy community, young men are prone to despair that can end in addiction or suicide, or to a quest for meaning that can end in conflict and violence. This is not a problem that affects men alone, but the statistics around deaths of despair and rising violence show that it is affecting men in a particularly damaging way.

Recognizing Genuine Community

I have offered my clarifying thoughts and distinctions with respect to the way we think about community today, not because we need to guard old ways of using language, but because new ways of using language are obscuring really serious problems in American life, and in the life of much of the Western world. Neither should we arbitrarily deride technology. Communication technologies, remember, are trade-offs; they are rarely all good or all bad. At the same time, we need to gain a real understanding of what those trade-offs are, neither being fooled by mere optimism nor reacting with fear, but being clear-eyed about the changes that are taking place.

In a speech he delivered in 1998 titled “Five Things We Need to Know About Technological Change,” Postman said that “embedded in every technology there is a powerful idea. . . . To a man with a hammer, everything looks like a nail. . . . Every technology has a philosophy which is given expression in how the technology makes people use their minds, in what it makes us do with our bodies, in how it codifies the world, in which of our senses it amplifies, in which of our emotional and intellectual tendencies it disregards.” Computers, he thought, bias us toward information rather than knowledge and wisdom. We might say that the internet likewise biases us away from the formation of real communities. The internet is excellent at connecting people all over the globe to information, but the idea it contains is that community can be reduced to that exchange of information. In fact, community is fully found only in the kind of shared life that occurs beyond the bezels of our favourite devices.

Postman believed that technological change tended to shape every aspect of the world around us, and that its danger was that it would set the boundaries for our thinking. The major risk Postman identified is that we might begin to accept technology as a part of nature, as though it were the inescapable way of things. We have to remember that these are our tools, and they should be shaped toward our well-being and flourishing. We should not adjust life to fit the tool; we should adjust the tool to fit us. Those who have authority over technology, then, whether they be parents, teachers, institutions, or even government, should not be afraid to change the status quo in service of more human values.

Local community is no guarantee of virtue, but it is within the context of real community that we have our best hope for flourishing together. Reclaiming the word “community” from the mythology of the internet might be a start to rebuilding real communities where we live.