In memory of Jock Zonfrillo (1976–2023)

T

The Open Door

Of all the beauty found in writings on hospitality, some of the most luminous can be found in religious writings about pilgrimage. The Christian tradition tells us that for nearly two thousand years people living as far south as northern Africa, as far north as Scandinavia, as far west as modern Spain, and as far east as modern Iraq stepped out of their shelters, wrapped themselves in whatever cloth was theirs, and set out on sacred journeys—holy pilgrimages—across the remoteness of their worlds.

Like all human endeavours, these pilgrimages were—and still are—driven by motivations at once varied and complex. Some set out seeking safety. Some sought adventure. Others sought simply the hope of beginning again. But no matter how varied their motivations, as these pilgrims stepped onto their paths and bent their bodies toward the long course before them, each spent their days scanning the horizons for one thing: a place of welcome.

Sometimes they found this welcome in private homes that doubled as taverns or inns. Indeed, in certain parts of Europe, many inns can trace their origins to ancient acts of hospitality to pilgrims. (As I write these words, my eldest child is sleeping in just such a place—called an albergue—on the Camino de Santiago pilgrimage route in Spain.) But as often as not, these ancient pilgrims found welcome in churches. Sometimes these were huge cathedrals, rising up in stone and filling up with light. Sometimes these were small parishes, tucked away on some side street and filled with quiet. Sometimes these were monasteries, cloistered behind walls and filled with song.

Whatever their size, each shared a common vocation: to welcome the stranger with bandages for their feet, a fire for their cold, a table for their hunger, a bed for their rest, and walls to protect them against the terrors of the night. And when those strangers had passed on, hosts at these shelters remade the empty beds, wiped down the empty tables, and re-set the empty chairs in anticipation of new strangers, new friends, to come.

Many of these church communities had manuals written to guide their members in the reception of these travellers. Consider, as one example, these words from the Benedictine Rule written in Italy in the sixth century:

All guests who present themselves are to be welcomed as Christ for He himself will say, I was a stranger and you welcomed me. . . . Once a guest has been announced, the superior and the brothers are to meet him with all the courtesy of love. . . . The abbot shall pour water on the hands of the guests and the abbot with the entire community shall wash their feet. . . . Great care and concern are to be shown in receiving poor people and pilgrims, because in them more particularly Christ is received.

Or, as another example, consider these instructions from a twelfth-century monastic order of the Knights Hospitallers of St John:

When the sick man shall come there, let him be received thus: Let him partake of the Holy Sacrament, first having confessed his sins to the priest. And afterwards let him be carried to bed and there—as if he were a lord—each day before the brethren go to eat, let him be refreshed with food charitably according to the ability of the House.

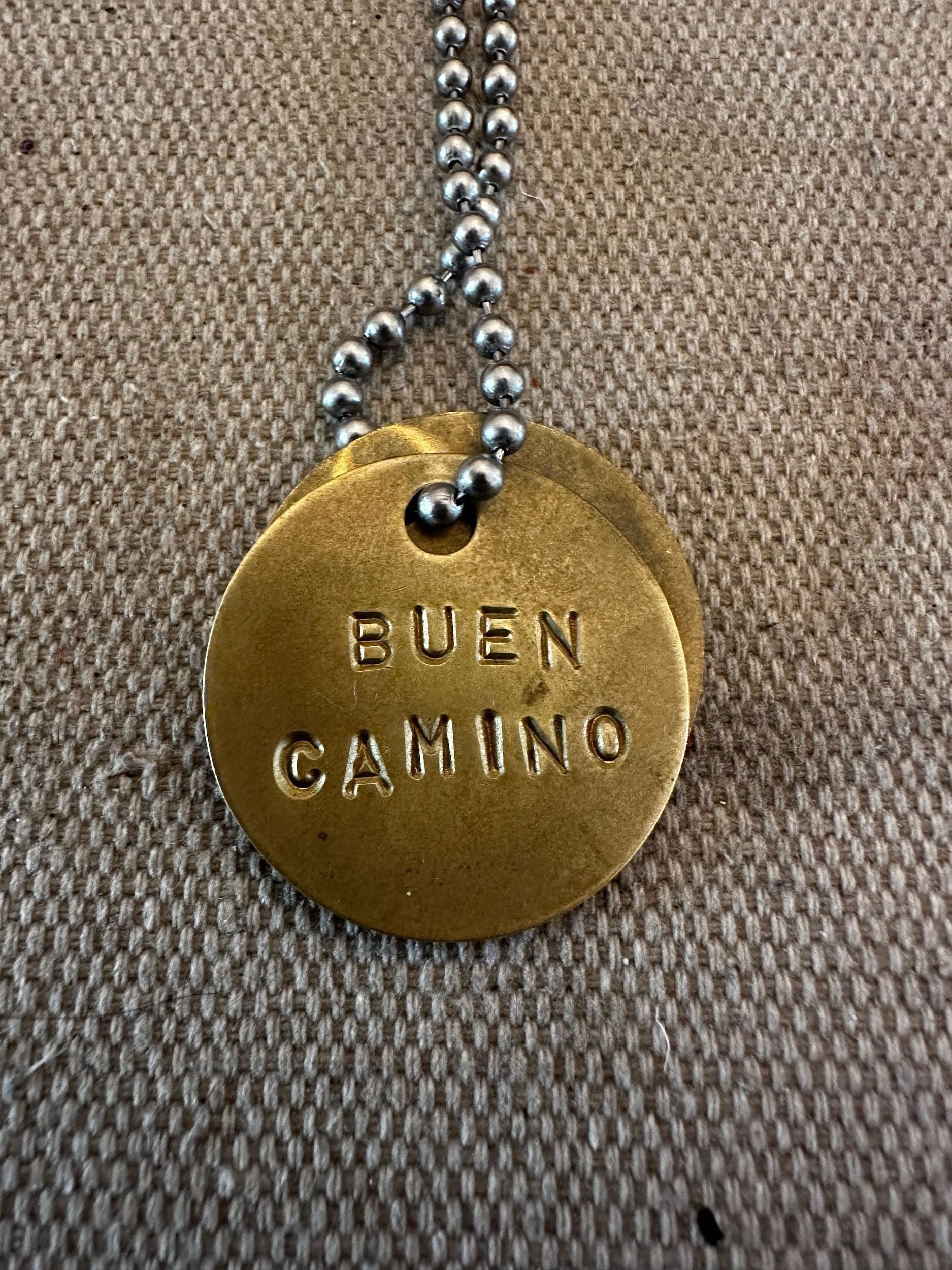

These are remarkable passages in remarkable documents, and there are a number of others like them, each bearing witness to deep conviction that a central part of the church’s vocation is the work of welcome. In the light of our windows these pilgrims found the consolation of knowing that they were not alone. In our greetings they found the kindness of recognition, in our kitchens they found the joy of fullness, in our rooms they found the relief of rest, in our chapels they heard the music of grace, and in our farewells they found warmer clothes, heavier bags, and blessings for the way ahead: Buen camino.

As one who is a Christian myself—though not a particularly good one—when I think back on our brothers and sisters who in times of leisure or crisis scanned the horizon looking to welcome weary travellers into warmth, fullness, and shelter, I find it almost indescribably beautiful. If there is a more compelling vision of what it means to be people of faith in the midst of this world, I honestly don’t know what it is.

The Unexpected Presence

When I started reading narratives of hospitality some years ago, I was—and remain—deeply moved by the twinned accounts of host and guest, these stories of vulnerable human beings wandering in the dark, and of the generous human beings who stood at the gate and kept watch for them. I see myself in both of these: at once longing for welcome and longing to extend it to others.

Lately, though, I have found myself drawn to another, somewhat unexpected aspect of these stories of pilgrimage, an aspect that I had somehow missed before: the presence of fellow pilgrims along the way. For years, perhaps out of some deep and native loneliness in my own heart, when I imagined these pilgrimages, I did so in largely solitary terms. The lone traveller, cloaked in worn wool, leaning against the rain and wind, searching the horizon for safety. The lone host, peering out from a single square of light in search of whatever weary heart emerged from the shadowed bend in the road.

The truth, however, is that pilgrimage has almost always been not a solitary act but a communal one. No matter how alone one may feel, there are always other pilgrims who are just ahead, just behind, or just beside us on the way. Each night, history tells us, as pilgrims took their places at firelit tables, there were almost always other pilgrims sitting at those tables, sharing in that warmth. These travellers would spend their evenings telling their stories, tending one another’s wounds, sharing their provisions, and sleeping beside one another in the dark. And, though virtual strangers, they would set out together in the morning, walking together as far as strength would allow. When the time for parting arrived, pilgrims often gave one another a token of affection, expressing the shared hope of walking together whenever roads converged again, and offering their own blessings—their own buen caminos—for the journey.

Pilgrimage has almost always been not a solitary act but a communal one.

Richard Frazer, in his 2019 account of walking the Camino, Travels with a Stick, describes just this experience: hours spent walking on roads, sitting in churches, and gathering around tables with strangers who—in the way of pilgrims—would become instant companions: “The freedom and trust of the Camino allows real friendship to arise and develop very quickly, and can be a genuine source of blessing even if it does not last more than a few miles or a pilgrim dinner.”

Upon reflection, I see that I have been drawn to this theme of companionship not so much out of historical interest as out of personal experience, the mid-life experience of renewed gratitude for my own fellow travellers, those men and women with whom I have travelled through light and through shadow. For all of my solitary illusions, the truth is that I have always been surrounded by companions who have not just shared my path but also lightened my load, nourishing me—step by step, conversation by conversation—with food for one more day.

Of these, one of the most recent and most beloved was the Scottish-Australian chef Jock Zonfrillo. Jock’s pilgrimage was extraordinary by virtually any measure. Born in Glasgow in the 1970s—a city depressed by patterns of poverty, neglect, and gang violence—he found refuge in the kitchen and in the community that orbited in and around the city’s restaurants. He took his first kitchen job at the age of twelve and, within a year, was a regular fixture on the line.

By his own account, this culinary community was at once welcoming and brutal. On the one hand it made space for a preteen boy to explore his love of food and interest in cooking. But restaurant life was also normalizing of violence, abuse, and self-destruction; Jock took all of it. At age fifteen he left school and apprenticed in the kitchen of a prominent Scottish golf resort, and by age sixteen—just four years after he began cooking—he was named Young Scottish Chef of the Year and secured a place in a Michelin Star kitchen. He was soon working in the kitchens of luminaries like Marco Pierre White and Gordon Ramsay and then, at age twenty-two, was appointed head chef at Hotel Tresanton, one of England’s most elegant hotels.

As Jock’s culinary star rose, however, the brutality of the industry drove his personal life into chaos. Surrounded by a culture of casual drug use, he became addicted to heroin, an addiction that would plague him for over a decade. And because of both the itinerant nature of restaurant work and the economic drain of addiction, he became homeless—sleeping in the locker rooms and mop closets of the kitchens where he worked.

In 2000, as a twenty-four-year-old chef, Jock emigrated to Australia for love and for work and, when he arrived, quit heroin once and for all. These two decisions—to change countries and to renounce drug use—transformed his life. Unsurprisingly, part of this transformation took place in the kitchen. As he began to work in Australian kitchens, he noted that “Australian cuisine” largely ignored both indigenous Australian ingredients and their traditional preparations. This insight led Jock to visit dozens of Aboriginal and indigenous Australian communities in order to understand the ingredients, preparations, and communal significance of their foodways. In time, this obsession became a mission: to transform Australian cuisine by infusing it with the indigenous ingredients, preparations, and stories that—as in so many societies of colonial heritage—were too often ignored. This led him to open Orana, a restaurant whose menu was wholly ordered around indigenous foodways and, in time, to found the Orana Foundation, an initiative to understand, celebrate, and promote indigenous foodways across Australia. These initiatives led to a host of awards, international recognition, and, in 2019, to his selection as a judge on the influential television show Master Chef Australia. After years of struggle, Zonfrillo had become one of the most influential young voices in international cuisine.

And yet, in another one of the important decisions of his life, Jock used the opportunities created by his public success to enter—for perhaps the first time in his life—into a period of private self-reflection. He began purposefully to look at the road he had travelled and to acknowledge its pain and heal from its wounds. And he also began creatively to consider the road to come—not only as a chef but as a husband, father, and friend—and to reimagine its possibilities.

It was during this period of vulnerability and deliberate healing that our pilgrim paths converged. We were drawn to one another by a shared love for food and for cooking, a shared concern for the marginalized foodways of our respective cultures, and a shared love of what he (in that most inelegant of British phrases) called “taking the piss” out of one another. But we were also drawn to one another by a shared understanding of pain. We both knew the trauma of abuse, the chaos of addiction, and the yearning for healing that follows in the wake of these things. And we were both in seasons when we were actively and deliberately seeking that healing. It was these shared loves, pains, and hopes that drew us together and fused us into something akin to brothers.

We spent our days together talking about the proper calibration for coffee machines; telling the stories behind cuts, burns, and tattoos; and holding forth on the proper method for making carbonara (no cream, he rightly insisted). We talked about indigenous food, African American food, and Italian food. We talked about restaurants, hospitality, and our future hopes for our respective cooking. But we also talked about our pasts and the wounds we bore from them. We talked about our wives and our children. We talked about the men we wanted to be—for ourselves, for those whom we love, and for the world we steward.

The last time we were together, we sat on the porch late into the night dark and shared a pack of American Spirits (he blew annoyingly perfect smoke rings) and made plans to take our wives on a pasta tour through the trattorias of Rome. The following morning before he drove away, we exchanged gifts. He gave me a recipe for his favorite pasta dish (cacio e pepe), and I gave him a handmade pendant that I wore inscribed with my favourite blessing: buen camino.

The Sudden Departure

On Monday, May 1, 2023, I woke to a phone filled with messages. In the race to get my kids to school on time and my desire to be present with them on the way, I decided to wait and listen to the messages after drop-off. But as I grabbed my keys, I noticed a call coming in from one of the numbers whose calls I had missed during the night. I decided to answer it. And there, standing (of all places) in my kitchen, I heard the news that Jock was dead. That he is dead. Seeing the look on my face, my wife took the keys, took the children, and left me mercifully alone in the grey disbelieving silence that followed the news.

Here, as best anyone can tell, is what happened. Jock travelled to Melbourne to film a few commercials and participate in a gruelling round of media appearances in preparation for the launch of the latest season of Master Chef Australia. He was, by all accounts, doing well. In fact, he called from the studio to tell me about a “prawn schnitzel” recipe (I had never heard of such a thing), about the brutally long days he was working, and about how much he was looking forward to the respite of a trip to Rome with his wife and kids in the coming days. He sounded great. And then, two days later, he died in his sleep from natural causes in a Melbourne hotel. He was forty-six years old.

I cried for two days. As in, I did virtually nothing but sit on the couch like a ghost as my family moved around me in love. I cried for Jock and for the future life that he lost. I cried for his wife and children. I cried for the hospitality community that had lost such an important mind and unimpeachable talent. And I cried for myself and the friendship—with all of its present joys and future hopes—that I had lost. I cried that the path that once stretched out before each of these had disappeared into a senseless emptiness. I still do. And, as is the way of loss, I am now in the process of gathering up the fading images of our time together and beginning the unwanted work of processing this new grief.

In the midst of the grief, I received an unexpected phone call from Jock’s wife. She asked me if I would be willing to help her not only plan the service but also come to Australia and lead it. Though Jock’s pilgrimage had suddenly ended, mine, it seemed, was just as suddenly leading me across the world to stand at his grave.

The Empty Chair

After nearly thirty hours of travel, I landed in Sydney—a city incongruously sunny and sea-breezed—and found a consoling home among Jock’s grief-stricken community of family and friends. They were, as you might expect, a warm-hearted group: deeply honest, utterly kind, instinctively hospitable. They welcomed me with knowing embraces, introduced me as “Jock’s American mate,” and set a place for me at their shared table. And so it was that, just a few hours after landing in a new place, I sat at a table with grieving strangers and shared a delicious pot of chicken Marbella as we told stories, shared sorrows, and raised glasses to the husband, father, and friend we had lost.

Due to the combination of grief and jet lag, the day of the service largely exists in my mind as a set of impressionistic images: The quiet chapel filled with flowers. The heather and thistle pinned to my lapel. The mournful break in the voice of the aboriginal man—dressed in a red loincloth and painted with white ash—as he welcomed us all to his people’s land and declared his people’s gratitude for Jock. The sound of the bagpipes as the service began. The slow procession of the casket, borne aloft by his wife and closest friends. The abject and disbelieving grief on the faces of his community. The voice of a child, reading one of Jock’s recipes aloud. The solemn procession to the graveside. The Gaelic blessing sung with such vulnerability. The vibrant colours of the Scottish Royal Banner across his casket. The feel of the thistles in my hand, and the sound they made as we dropped them into his grave. The embraces of his friends as we gathered for an after-service meal. Stepping into my customary place behind the bar, pouring glasses of scotch and wine for the weary-hearted. The table, laden with Jock’s favourite foods: charcuterie, steamed lobster, pasta, macaroni and cheese, Scottish shortbread. The quiet intimacy as we sat together and summoned memories of our lives with Jock. The knowing embraces as we parted from one another and drove away in the rain. Each of these now is frozen in mind and heart, ambient icons of beauty and sorrow.

Considering both the length of the journey and the needs of grief, I decided to stay in Australia for two more days after the service. My hope was not only to explore a place I’d never been but also to go to places that I knew Jock loved, to further enflesh him in my mind by walking paths he’d walked, eating meals he’d eaten. I took the obligatory selfie at the famed opera house. I meandered through “the Rocks”—Australia’s original colonial settlement—and sampled the food of no fewer than four street vendors in the course of half an hour (I can now vouch for the tastiness of grilled kangaroo). I took the ferry to one of Sydney’s many beaches and followed a coastal walk that he took with his family. I wandered through the sprawling Royal Botanic Garden and searched for his favourite indigenous plants. And I spent hours shuffling through art museums, learning—for the first time—about Australia’s indigenous culture and art. Each of these was lovely, but each was also haunted and painful. After all, nothing quite cements the reality of loss as powerfully as inhabiting spaces where your loved one dwelled, but dwells no more.

On my last night some of my new friends made a reservation for me to dine alone at one of Jock’s favourite restaurants. Marta is a lovely Italian restaurant tucked away in one of the neighbourhoods just outside Sydney’s city centre. The chef, Flavio Carnevale, is an émigré to Sydney from Rome (“for love, what else?”) who brought his native city’s culinary magic with him. Jock once told me about the restaurant, and we made—in the way of friends—a promise to meet one another there on some warm night. And yet on this night, in yet another poignant moment of loss, I walked to the restaurant alone in the midst of a storm.

Flavio had attended the funeral service and so recognized me when I stepped out of the rain and into his lovely space. He greeted me with an embrace and led me to a seat at the bar he had already prepared for me.

With a knowing look, he set an empty chair beside me. “For Jock?” I said. He nodded, placed his hand on my shoulder, and stood with tears streaming down his face. He said, “Jock was a brother to me. And you are now a brother to me as well. Tonight, I will give you the meal that you and Jock should have shared.” He disappeared into the kitchen.

Jock once told me that Flavio was a master of Italian cooking. The next three hours showed me why. It was a marathon of delight, with course after course of perfection, each brought to my place by Flavio himself. The evening began with a perfect Negroni, made of organic ingredients shipped directly from Rome, and gnocchi fritti, fried gnocchi blanketed with pecorino cheese. Then he served suppli, a lightly fried ball of golden rice filled with creamy mozzarella and sauced tomatoes. Next, he served burrata with tomatoes and a steaming plate of “you musta try my homemade” focaccia. He paired these with a romato, an “orange wine” (wine fermented with the skins still on) from northern Italy. After this, he brought out Jock’s favorite, cacio e pepe, and paired it with his house wine, a sturdy Roman red.

Sensing my withering will, he attempted to revive me with the news that I was now over halfway through the meal, and by making me what he called a bourbon Negroni (essentially a Boulevardier) made with rye whiskey, Del Professore Italian vermouth, and—in place of the traditional Campari—an organic Walcher Venticinque Bio Bitter. It had the intended effect, fortifying me through a course of polpette (a veal meatball served with tomato sauce and pecorino) a Colosseo pizza (a full pizza topped with potato, mortadella, burrata, and truffle paste), and a large plate of (cream-free) carbonara. To prepare me for dessert, and in honour of Jock, he poured me a class of Bunnahabhain scotch and then served me his extraordinary sfogliatelle, a crispy layered shell pastry filled with ricotta and orange. Every course was perfect, a testimony to Flavio’s genius, and a justification of Jock’s riotous delight in Flavio’s food.

As the meal came to a close, I realized that Flavio and I were the last people in the restaurant. I asked him for the bill, and he waved me away, telling me, “I am serving you as a brother, not as a customer.” After clearing the plates, he told me that one last thing remained—a toast. Opening a bottle of Vivese amaro, a warm, herbal amaro from Naples, he poured two glasses and set one in front of each of us. Sitting there in the now quiet restaurant, with the rain falling outside, we raised our glasses and looked at one another. The only words either of us could manage were, “To Jock.” After promising to cook for him on his next visit to America, we embraced and set out—in the way of pilgrims—in search of home.

Looking back now, I see that out of all of the tears, travel, words, and wandering of those brief days Down Under, it was sitting there with Flavio, eating that meal and drinking that toast beside the empty chair, that was—perhaps—the purest expression of both my love for Jock and my grief over his death. Indeed, of all the things I had done since his death, this was the one he would have loved the most. All told, I traveled nearly sixty hours to sit at that bar. And I would do it again without hesitation.

If I could change one thing about that evening, however, it would be the words of my toast. As I said, I was too sad of heart and full of magic that night to manage much more than “To Jock.” But, had I the presence of mind, this is what I would have said: (raising a glass) “To Jock—husband, father, chef, mate, and fellow traveller. Just up ahead there is a place with strong walls, a warm fire, and a table full of every good thing. I’ll meet you there. Buen camino.”