W

What exactly does protesting accomplish? In general, not much. A few powerful, transformative protests have shaped our collective imagination to expect that mass action will lead to positive change, but most public protests accomplish none of their stated goals. Many protesters like to think that by making a bold stand in public they are imitating the heroes of the civil rights era or the Boston Tea Party. Most of the time, however, they’re just imitating Occupy Wall Street (a public action that never had a specific goal and succeeded in accomplishing nothing) or January 6 (a public action that had the very specific goal of preventing Joe Biden’s accession to the presidency and succeeded mostly in making the public less favourable to the movement). The idea of protest may animate people who are passionate about a cause, but real change usually requires a different kind of work.

Consider the case of Just Stop Oil. (Personally, I would like to stop oil from staining my clothes when I spill salad dressing on myself, but I doubt I could get anyone to march for that.) Just Stop Oil protestors have blocked motorways, thrown various liquids at priceless works of art, and attempted to disrupt other public events. Their stated goal is to end new licences for oil and gas exploration in the United Kingdom, which is not even in the top ten oil-producing countries in the world; it is unclear to what degree this particular policy change would affect the consumption of fossil fuels in the UK or elsewhere.

One might argue that just by talking about this particular group and their cause, I have underscored the value of their protest. If all attention is good attention, I suppose this might be correct, but bringing a subject into the discourse with greater clarity does not in any way guarantee meaningful change. With very public actions that range from the annoying to the dangerous, Just Stop Oil’s protests may not have changed public opinion for or against oil and gas licensing, or they may have inclined public opinion against their cause. When a protester steps out into the street or buys a can of soup for hurling, they can’t predict what effects their action will have.

The operating assumption in this case (and many others) seems to be that once the public’s mind is drawn toward a particular issue, they will be compelled toward some kind of positive action. The moral and intellectual weight of the cause being agitated for is assumed prima facie, even though this isn’t a fair assumption. The best-case scenario is that a motorist whose car is stopped by protestors might use the opportunity to research the oil and gas industry and then later vote or write to their local elected leader about the issue. The worst-case scenario is that a person is annoyed by the protest so much that it influences them to vote against Just Stop Oil’s aims or makes them care less about their personal use of carbon-burning technologies.

Protest allows someone to feel like they are doing something about a problem, but a momentary burst of outrage is hardly enough to make any difference. The feeling of anger one experiences when contemplating transnational injustices like climate change, human trafficking, racism, abortion, or the promotion of sexual deviancy quickly turns to a sense of powerlessness, so marching or tossing paint might make someone feel like they are exercising what little power they have on behalf of the oppressed. That toxic stew of anger and powerlessness, however, is more likely to burn out the people experiencing it than change something on someone else’s behalf.

Similarly, posting online about an issue may give someone the feeling of efficaciousness in the world—especially when that post gets plenty of attention—but one only has to look at some of the most popular ideas and personalities online to see that online activism isn’t always successful. DeRay Mckesson was one of the most prominent Black Lives Matter (BLM) activists and had 300,000 Twitter followers when he ran for mayor of Baltimore back in 2016; he managed to get 2.59 percent of the vote (3,445 votes total) in his hometown. A co-author of one of the most popular books about Christian nationalism finished in fifth place when he ran for his local school board. Talking about an issue online is the easiest—and least effective—way to do anything.

In his review of Gal Beckerman’s The Quiet Before for Comment, Louis Kim discusses the critical “acts” that a social movement requires in order to succeed: private conversations, public demonstrations, and leveraging for power. He reports on one BLM group that worked diligently to develop the relationships with elected officials. This work translated into “hard power” that could then be used to direct funding toward less violent means of dealing with people suffering mental health crises. Months or years of marching or posting would have sucked up the same energy with nothing to show for it.

Part of the challenge is that if the problem is big enough or abstract enough, one can argue that culture-shifting “soft power” is necessary to deal with whatever crisis at scale and that “hard power” sufficient to the task at hand can only come after enough people have been memed, cajoled, harassed, or convinced to join in. This strategy, however, allows for perpetually open-ended crises and discounts the other predicament that mass movements often find themselves in: you can convince many people of the rightness of your cause, but they may or may not do anything for the cause once they’re convinced. If they were convinced through memes, they may think that their only job is to continue in the soft-power campaign. It is almost like a multi-level marketing scheme in which a few people recruit their friends, who in turn recruit their friends, and so on. But all that happens is that millions of catalogs get distributed without ever selling a single unit.

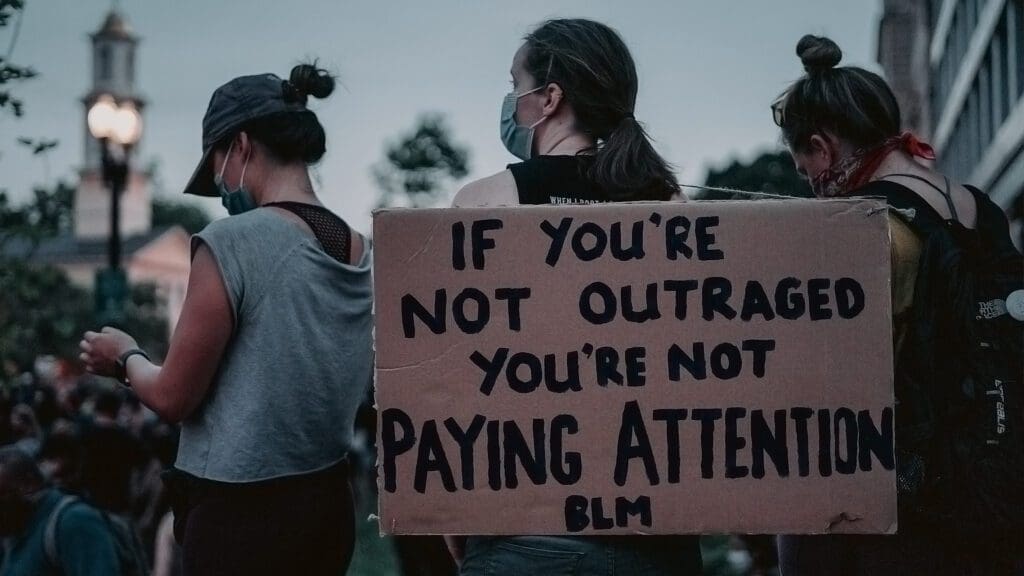

Consider the broader zeitgeist of BLM. It has been over ten years since the phrase “Black Lives Matter” came into public consciousness, following the acquittal of George Zimmerman in the killing of Trayvon Martin. It has been almost ten years since nationwide protests in the name of BLM broke out after Michael Brown was shot by Darren Wilson as they struggled over Wilson’s gun. It has been almost four years since nationwide demonstrations took BLM from an issue of public contention to a matter of institutional transformation after video footage of Derek Chauvin killing George Floyd by kneeling on his neck was released, prompting numerous companies (ranging from Walmart to Pornhub) to release statements about their commitment to fight racism.

One must be especially wary of mistaking one’s personal enthusiastic participation as efficacious.

Since then, billions of dollars have been given to the cause of racial justice, including millions of dollars directly to the various central Black Lives Matter organizations. Jobs in diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) rose dramatically after 2020 (although some of these positions have experienced more attrition in recent months compared to non-DEI jobs), and countless organizations have instituted some sort of mandatory training or education in DEI. Numerous initiatives in public education have been instituted (or opposed) to give American students a thorough background in understanding the historical and cultural dimensions of race in America. As Freddie deBoer puts it, “Social justice politics is the language of institutions; it’s hard to find a single university, non-profit, or major corporation that doesn’t use social justice language as its default public relations vocabulary.”

It is difficult to say, however, what exactly has been accomplished after spending all this money and expending all this energy. Matthew Yglesias points to some specific data showing that the use of force by police is slowly trending downward. Police wearing body cameras seems to be having a positive effect, while federal or state investigations of police departments seem to be less effective in “viral” cases of police misconduct and more effective when instituted more quietly. There is some data to suggest that, on the downside, BLM protests have also been associated with an increase in rates of murder, but this is very controversial.

Part of the challenge of judging a movement like BLM on its merits is the question of goals. If we consider the rather modest goal of decreasing the number of unarmed people who are killed by police, or decreasing the use of force by police in general, it is possible to say that this goal is being achieved and we are seeing slightly fewer sensational events of police brutality such as those that animated protests in the first place. However, the police still kill about a thousand people each year, most of whom are armed with some kind of weapon; and, given the wide availability of guns in America, it is hard to imagine that this number will change dramatically anytime soon.

If the goals of BLM are wider, that presents a different challenge. After all, it has been acknowledged by many that police killings of unarmed black men are merely the tip of the iceberg that racism in America represents. The discrimination, economic inequality, and decreased life expectancy that black people in America experience are moral imperatives, since they are clearly attributable to the legacy of racism. Yet these goals, laudable as they are, are far more nebulous and thus more difficult to accomplish.

Even more challenging is the fact that some of the most prominent BLM activists explicitly identify the movement as “abolitionist,” meaning that they wish to abolish the police and prison systems. This is a very unpopular proposition that is not getting any more popular. Despite the fact that BLM casts a holistic vision for an alternative society in which police and prisons are unnecessary, there is no roadmap from getting us from our current position to such an alternative society. Without such a roadmap, anyone who wants to support BLM tout court is left with only posting and protesting. Those who want to support BLM’s other goals or have specific reforms in mind will find themselves constantly fighting a rearguard defence against people who think that a bad system cannot be reformed, only abolished.

Accordingly, BLM’s dominance over our public consciousness has failed to reap the benefits many would have hoped. Most people have in one way or another encountered BLM’s arguments for themselves in the past decade, and representatives from practically every possible echelon of power have endorsed BLM. But as George Yancey puts it, “Antiracism is not truly for the benefits of people of color, but rather it serves certain sociological, and maybe even psychological, needs of the elite educational class.”

I don’t mean to single out left-wing causes here or universally paint these particular movements as ineffective. Many post-liberals on the right seem to be stuck in the same morass of meming themselves to death, and there are plenty of climate-change or racial-justice activists who are working to build the coalitions and write the bills that will make incremental but meaningful changes. For people who are animated by ideas and dwell primarily in realms of symbolic action, though, the temptation is ever present to think that dominating in the symbolic realm will necessarily trickle down into reality. One must be especially wary of mistaking one’s personal enthusiastic participation as efficacious.

Growing up in conservative American evangelicalism, I found that a lot of thinking about big-picture problems was so holistic as to be nihilistic: everyone had to dramatically change themselves for things to change. Major social issues (or problems within the church) would change only after enough people converted to Christianity and enough Christians were sufficiently adherent for things to change. This is a lovely sentiment but no more than that; it’s a worldview that allows those who hold it to justify the status quo indefinitely.

It’s easier to destroy something that works poorly than build something that works well.

By contrast, anti-abortion activism in the United States is the dog that caught the car when Roe v. Wade was overturned. Over the last several decades, conservatives slowly accumulated hard power against abortion through the judiciary and eked out legislative victories state by state, while many of the cultural factors upstream of abortion stayed the same or got worse. There are fewer abortions in the United States now than there were five years ago thanks to Dobbs, and that’s a good thing, but it’s difficult to know whether there’s been enough change in soft power for these improvements to hold.

Speaking about the need for total, systemic change in the face of a crisis feels like a powerful insight. To speak of the need to abolish capitalism or to seize power so that you can use the power of the state to reverse the moral rot in the world animates the activist mind because activists feel it in their hearts. The problem is that it’s extraordinarily difficult to get people to agree with you en masse, much less change significantly. Most rapid large-scale changes that do manage to make an impact in the real world tend to be negative or destructive; it’s easier to destroy something that works poorly than build something that works well.

Holding ideological views that are so holistic they’re nihilistic is a fun hobby, one that many people cherish. But it makes no sense to get mad that the rest of humanity isn’t getting with the program and to complain that no one else wants to adopt your ideology wholesale. Especially when you’re in a democracy, you have to accept that people are only willing to make incremental changes and accept a mild amount of pain with each change—if they’re going to change at all. If your way has never truly been tried, you may have to accept that it won’t ever be.

Given these hard realities, it becomes even more important to ask, What is worthwhile and worth pursuing? So far I have focused on tactics and goals. It’s difficult to pivot to these mundane questions if you (like me) grew up imbibing the rhetoric of “changing the world” and find yourself deeply moved by the struggle for justice, but it’s necessary. The most successful movements have both goals and tactics for how to achieve them. Even if you have a big-picture view of the world that requires some kind of massive social and cultural change, there must be an immediate step that people can take.

Because climate change is a worldwide problem, carbon dioxide emissions may not significantly reduce even if Western governments agree to radically reduce emissions within their own countries. The radical abolition of capitalism that many climate-change activists long for as the underlying solution to climate change might not make that much of a difference. Many of the world’s worst polluters are countries run by autocratic governments not susceptible to protests, and many developing countries will naturally increase their emissions as they raise their standard of living to get anywhere near ours in the West. We cannot count on reducing energy consumption overall.

Perhaps the people who believe that climate change is truly an emergency need to get out of the street and into the lab.

Thus, reducing carbon dioxide emissions will require alternative energy sources and significant technological changes—a different set of tactics and goals. For example, scientists at Purdue University recently revealed that they manufactured heat-reflecting paint that could dramatically reduce the need for air conditioning. This is the sort of innovation that could have dramatic effects on mitigating climate change, which means that more energy and effort needs to be put into developing innovations like this one. The development of nuclear power has stalled (in no small part due to misguided environmental activism), but it’s hard to imagine a path forward without it. Even “greener” forms of energy like wind and solar have major environmental downsides due to the extraction process for the minerals they require, which means that we’ll need other breakthroughs to make them more efficient. Perhaps the people who believe that climate change is truly an emergency need to get out of the street and into the lab.

What about Black Lives Matter? Here, I would argue, the goals of the movement must be defined and agreed on among its most prominent voices, which also entails delegitimizing dissenters that might drag the movement down. It is possible that in some ways this has already happened—some of the most prominent BLM activists have gone all-in for the abolitionist tack, which is making their movement as successful and relevant as Catholic sedevacantists and modern French monarchists. Again, I begrudge no one their deeply held holistic theories of the world; I only ask which efforts are going to result in meaningful change rather than just memes.

The most persistent and pernicious effect of racism has been concentrated poverty in formerly segregated places. Many of the other ills that catch our attention, such as violence, are often downstream of this concentrated poverty. There is no shortage of debate on the best ways to address these problems, but ultimately for Black Lives Matter to mean something, it has to mean something specific. As the movement ages into its second decade, it’s worth getting very specific about what it ought to stand for.

Posting memes and rallying in the streets can give an ephemeral feeling of success in advancing one’s cause. That sense of victory, however, is often little more than just a feeling. Changing the world requires a different kind of patience, paired with careful thought about goals and tactics to ask what will convince the people whose behaviour needs to change. Large-scale change requires more than passion—it requires a strategy for getting people who might not see the world as we do to trust us and take slow, deliberate steps toward making a difference.