I imagine that the subtitle of this piece might give some readers a moment of discomfort. “Uncompromising” is a descriptor more often associated with fidelity, steadfastness, commitment, and wholeheartedness—biblical virtues richly developed in the stories of paragons like Abraham, Job, and John the Baptist. “Uncompromising” is an inspiring idea—except when it comes with hardness of heart, bigotry, and insularity. I imagine we have all met people whose uncompromising positions leave no chink open through which even a small beam of new information might enter.

The term “compromise” cuts both ways, sometimes in the same conversation. David Harris, executive director of the American Jewish Committee, recalls Ariel Sharon as “a man of towering strength, uncompromising commitment, steely determination, and creative vision,” while Shlomo Avineri, former director-general of Israel’s ministry of foreign affairs, speaks with some contempt of Arafat’s “uncompromising and belligerent behaviour” at the Camp David talks.

Predictably, proponents of compromise attract condemnation. They are selling out, giving up the good fight, waffling, wavering, pandering. The words of Allen Domelle, one outraged defender of the faith, might be heard in pews and pulpits across the land:

Throughout the years, I have watched and studied good men who’ve compromised. From my childhood through today, I’ve watched men who I once looked up to become men with whom I could no longer associate. Compromise sets in, and their works and messages have become the very examples of what they used to preach against.

Compromisers compromise the integrity, purity, clarity, reliability of what we, the faithful, most count on, and we must drive them from our fortresses to die on their own slippery slopes.

When the implications of a political, philosophical, or theological position are far-reaching and consequential, discussions tend to polarize. The centrifugal force that pushes us away from a stable centre in the whirl of public discussion makes compromise look not only unsatisfying, but nearly impossible as the stakes escalate. The more personally invested we become, the harder it is to accept the idea that one might compromise with integrity. Face-saving is a powerful motive. Being right is a heady pleasure. Absolute conviction looks a lot like strength and security.

The middle way is not glamorous. By definition it lies in the grey area, often in foggy, uncharted territory. Sometimes in a swamp. The trails that lead through it are not blazed so much as hacked out around rocks too big to move and through bogs and thickets that take tiresome hours to penetrate. The middle way is often charted by committees—people with competing agendas assigned to find common ground and often too tired or threatened or entrenched to do their work with grace.

Nor are the virtues associated with compromise heroic. They begin with humility—arguably the most challenging of all virtues, though perhaps a basis for all the others. Faithful compromise requires flexibility, imagination, empathy, compassion, a sense of humour (which I consider a core virtue), and trust in the Spirit in whom we live and move. Perhaps “move” is a key word here. While we live, we move. The world turns. Cells reproduce. Children grow up and surprise us. Old conflicts arise in new situations. Language slips. Water shortages and nuclear weapons reorganize our priorities. We are broken and mended and our changed hearts change our minds. In the midst of all this, fidelity is redefined. “Love changes,” Wendell Berry writes in a poem about marriage, “And in change is true.” All these processes are fuelled by “the force that through the green fuse drives the flower”—a force that never rests—and every flower it fuels is a new creation. The dynamic character of all life offers us a daily and visible parable: what is alive takes new shapes, shifting light changes what we see, the hummingbird hovers and is gone, and every solid fact floats on a sea of mystery. So perhaps our efforts to achieve security, stability, continuity, and rock-solid arguments are less compatible with “choosing life” than we might like to think.

Keats gave a name to the habit of mind that enables strong-minded, faithful people to tolerate the messiness of ambiguity, uncertainty, blurred edges, and shifting boundaries: “negative capability,” he claimed, was that magnanimity of mind that makes one “capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.” The negatively capable can cope with ambiguity, mitigating circumstances, X-factors, and waves that behave like particles. They can reframe. They pay attention to intuition and the currents of feeling and dreams that provide information that can’t be quantified. They can imagine that sometimes the opposite is also true. They can hold what they believe firmly but are ready to loosen their grip a bit when new information comes in.

One of the truths great compromisers do hold to and honour is that, as Ellen Goodman once put it, “The bottom line is always ‘It’s not that simple.'” What is true for human beings is true in the context of a dynamic biosphere, a shifting economy, new threats to survival or relative peace, and fluctuating leadership. What is true for human beings “holds” true only by being revisited, reframed, reconsidered, and reimagined repeatedly. The implications and applications even of eternal truths may be parsed differently as needs and emphases shift—as we try to fathom the call of the moment, knowing there is a time for every purpose under heaven.

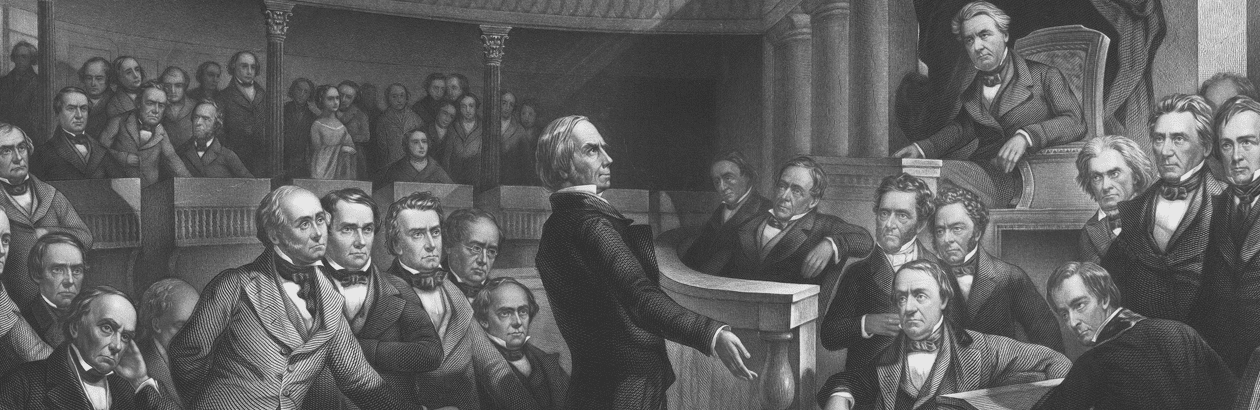

In moments of crisis the call for compromise has brought forth a particular kind of genius. No doubt, in an issue devoted to the theme of compromise, others will mention Henry Clay, dubbed “the great compromiser” by a restless antebellum public, and revered by Lincoln, among other notable peers. Clay crafted the Missouri Compromise, talked South Carolina down from nullification, and prevented Andrew Jackson from using force against the state. At calculated cost to people on both sides of bitter disputes, he found a middle way. Whether those costs were too high is still a matter of vigorous debate. Certainly the Missouri Compromise compromised the welfare of one of the world’s most oppressed populations even further by allowing a new slave state into the Union. Clay’s efforts to craft a bill that allowed South Carolina to save face in a hot debate over a state’s right to nullify a federal law avoided an armed confrontation, but failed to resolve the economic plight of southern farmers. His remarkable diplomacy forestalled Jackson’s use of force, but was arguably no more than a band-aid on a gaping and festering wound and a temporary stay against a president’s recurrent resort to violence. Yet each of these famous compromise measures rested on an astute assessment of the greater good: saving the union at the expense of a pure abolitionist policy; preserving the precedence of federal law over decentralization of power that would have paved a piecemeal road to political chaos; pruning when some would rather have laid an axe to the root of the tree. A review of a recent book by Robert V. Remini, At the Edge of the Precipice: Henry Clay and the Compromise that Saved the Union, makes this point about the wisdom of Clay’s pragmatic politics: “Clay was never rigid in his ideological thinking. He understood that politics is not about ideological purity or moral self-righteousness. It is about governing and if politicians could not compromise, they would never govern effectively.”

He also understood that compromise always comes at a cost. Calculating that cost is a matter of discernment—a prayerful seeking of the Spirit’s guidance—focused on the question, “What can I afford to let go of for the sake of what I hope to achieve?” There are other important test questions that help hold the necessary tension between compromise and holding fast to a position that deserves to be held: What is the greatest good in this situation? What are my deepest purposes? What am I protecting? Why do I think it needs protecting? To what extent is my commitment to my position a matter of informed faith and rational conviction, and to what extent does it involve my own pride, need to save face, desire to avoid appearing inconsistent, loyalty to a cohort who share the positions I’ve taken publicly, desire to keep a job, a congregation, my constituents’ loyalty? Have I considered all available evidence? What am I loath to consider? When have I resorted to contempt, caricature, or other strategies of dismissiveness to avoid engaging with views I find threatening? A lot of these questions, of course, have to do with the ways we justify and make legitimate positions that serve the devices and desires of hearts that are “deceitful above all things and desperately wicked.” Questions like these serve as instruments of discernment to keep clear the distinction between fearful and faithful compromise.

Faithful compromise—the kind we are called to every day of our individual and collective lives, in marriage, in parenting, in spending and stewarding, in collective decision-making and corporate practices— can be distinguished by a few reliable hallmarks:

- Faithful compromise allows for vigorous, impassioned, robust argument. Well-conceived compromise isn’t weak, and doesn’t come from lack of conviction, but rather from sufficient clarity about one’s convictions to distinguish between what is essential and what is expendable for the sake of a greater good than might be served by one’s original agenda. Ideally, it is a creative process that makes those involved in the argument more partners than opponents and awakens in both a real desire for a new, more capacious way of achieving what they hope for most.

- Faithful compromise takes the power differential into account. Most often the party in power is the one who can best afford to propose compromise. If one party is negotiating for survival while the other is negotiating for greater convenience or protection of privilege, the process can only proceed with integrity if part of the stated purpose is to promote justice. Racial reconciliation efforts that involve one group with a history and condition of privilege and one that is historically and economically disadvantaged have to begin with some recognition of who can afford to relinquish more in an effort to achieve a fair agreement. The long deadlock that has yielded no workable compromise in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict offers a valuable illustration of the fact that valid compromise has to take the power differential between parties into account. In her thoughtful article, “The Terrible Pangs of Compromise,” Trudier Harris observes that in the history of attempts at compromise between whites and African Americans, “Interactions are so troubled and painful that they more frequently result in abortion than in healthy deliveries.” A “healthy delivery” of a newly reconciled life together would surely suggest that those who have more give more, and that their vision of justice take full account of the debt owed to the poor and disenfranchised. Generosity can grow where justice flourishes, but justice has to come before any serious attempt can be made to arrive at generous compromise.

- Faithful compromise works toward a carefully, mutually defined common purpose (survival, for instance, or cessation of violence). The process of defining that purpose might itself take much of the negotiation time. Surprisingly often “road maps” that purport to aim at peacemaking flounder when it becomes clear that the parties maintain separate and opposed agendas with very little space in the centre of the Venn diagram.

- Faithful compromise is not necessarily the same as moderation, or meeting in the “middle.” It may come from a wild idea—from “out in left field,” and offer an adventurous third way no one had imagined before negotiations began. This kind of compromise seems to me often the way the Spirit works. The decision to explore a third alternative can already be a breakthrough to fruitful, imaginative, generous negotiation.

- Faithful compromise requires a commitment to non-recrimination. It is easy to forget, after the fact, that a compromise is a commitment, equally binding on both parties who share responsibility for the final agreement, even if one comes away feeling that earlier hopes have been disappointed. For this reason it is likely that good, workable, equitable compromise takes time; agreeing too early can undermine wholehearted commitment to work within the boundaries the agreement defines.

- Faithful compromise is practical and practicable. It recognizes the real needs of both parties. If those of one party are greater than those of the other, it takes that difference into account. Thus, the wealthy may be asked to accommodate more than the poor in crafting tax policies to ensure that everyone’s basic needs are met before privilege is protected.

- Faithful compromise handles language with care and integrity. We all know that language can be manipulated to provide legal loopholes, cover hidden agendas, and mask preferential treatment. It is in crafting the language of an agreement that people of faith may be most challenged to maintain scrupulous honesty to maintain its integrity and viability. Even in speaking about the process, we reach for metaphors that only provide an incomplete understanding of a complex process. “We talk about reaching a meeting of the minds, striking a balance, finding a happy medium, or meeting someone halfway,” Jeffrey Nunberg writes. “Before Shakespeare’s time, in fact, English lacked a single verb for compromise.”

- Faithful compromise requires prayer, generosity, humility, and grace. At every step, the process of compromise offers an opportunity to open our hearts, practice our faith, revisit the beatitudes, imitate Christ, invoke the Holy Spirit, and remember that we are dust, called to be the light of the world. It is a skill and an art, but can also be undertaken as a spiritual practice and cultivated as a habit of mind—a disposition toward others that asks, first, how can we meet in a way that fosters shalom? How can we approach our differences as an invitation to reflection and growth?

There is, no doubt, especially now, in the face of unabashed profiteering, debased public discourse, and perpetual warfare, a time to declare, “Here I stand; I can do no other.” Each of us needs to pray for the courage to hold fast to what is most deeply true. Yet even as we do that—even as we align ourselves with the poor against those who exploit them, with the oppressed against those who deprive them of bare essentials, with the imprisoned against those who corrupt the justice system for private gain—there is room to ask ourselves how to reach out with imagination and clarity and, wisely as serpents, find our way into fruitful conversation with the enemies we are asked to love.