I

In December of 1987, the famed evangelist Billy Graham approached a Denver stage with loneliness on his mind. Denver, at the time, was composed of a high percentage of unmarried persons, an urban centre on the verge of football greatness. Graham began his sermon by enumerating the various ways in which humans cope with the feeling of separation—alcohol, drugs, sexual activity—and said of the social condition, “The roots of loneliness were planted in the human soul and it has been inherited by every inhabitant ever. . . . Loneliness has never been a respecter of persons. The world’s greatest artists, writers and composers, kings and queens and carpenters and plumbers and everybody, have felt this terrible thing called loneliness.”

In naming loneliness as a ubiquitous cultural condition, Graham was entering into a long train of those who have sought to theologically diagnose the increasing malaise and loneliness of the modern world. But what exactly is this loneliness? What is it caused by? And does Christianity offer anything in response?

The Long Career of Loneliness

In the vast literature surrounding it, loneliness’s definition is contested. At minimum, it refers to emotional feelings of disconnection from others, but beyond this, the roots of the experience run deep and wide. For some, it is a sense of disconnect between one’s accomplishments and one’s social connections with others. For others, loneliness connotes the alienation experienced as one matures into adulthood and leaves the intimacy of family behind. But the varied descriptions of loneliness have this in common: the complex feeling of being out of joint with others, possibly—as with Psalm 88—to the point of despair. Graham’s assumed definition of loneliness—of being alone and unknown, feeling divided from others—squares with most of the reflections on the topic. But Graham approached loneliness as a theological condition, rooted in a division from God, which seems almost revolutionary, even among Christians. He also said that day in Denver, “In that garden God went looking for Adam. He knew where he was. . . . He wanted Adam to know where he was. He said, ‘Adam, where are you?’ And Adam tried to hide. . . . But he couldn’t hide.” By the time Graham took the stage, loneliness had a long history already, and theology was scarcely part of it. For while Graham traced this phenomenon back to Adam’s division from God—making loneliness part of the human condition under sin—loneliness had been discussed for nearly a century prior as a discrete problem of the modern age.

What if loneliness is simply a condition of being human, whether Christian or otherwise?

Beginning in the nineteenth century, loneliness became the obsession du jour, subject to inquiry from almost every branch of human knowledge. Interest hadn’t waned by the twentieth century, which saw a new spate of studies, including David Riesman’s The Lonely Crowd and Frieda Fromm-Reichmann’s seminal essay “Loneliness.” As cultural historian Fay Bound Alberti notes, the language of loneliness is relatively novel: the phenomenon of feeling separate and unknown has been experienced throughout human history, but descriptions of oneself as separated appears seldom prior to the nineteenth century. Her own analysis of loneliness shows the way in which the rise of modern forms of work goes hand in hand with estrangement from others: when people are told that their existence as a person is wrapped with their individual agency, industriousness, and economic value, competitive societies and economies will follow. And a society based on a shared assumption that everyone around you is your untrustworthy competitor will surely yield a harvest of division and a bounty of loneliness.

But linking loneliness to capitalism’s conditions alone may be too strong of a connection. As the late John T. Cacioppo described, it is highly probable that loneliness is adaptable to any human condition, because it is simply part of what we are as humans. Cacioppo’s work in developing the field of social neuroscience pushed clinicians and counsellors to consider that loneliness is not simply a feeling of being out of joint or unknown but is embedded in the very structures of our brains. Our brains are better characterized as “social brains,” he writes, emphasizing the biological dimensions to the phenomenon of loneliness. In Alone Together, Sherry Turkle amplifies this conclusion: our bodies desire human connection, and a world mediated by digital devices does us no favours.

These basic presumptions of loneliness as a cultural problem endemic to the modern world were adopted by Christian thinkers as well, but they did not primarily see it as an economically generated problem. Loneliness, the assumption went, was a social condition; while economic systems were seen as playing a role, other related culprits such as technology, social fragmentation, or decline of involvement in professional and civic organizations began to surface, as diagnosed by Robert Putnam in his influential book Bowling Alone. The solution to loneliness must be, therefore, more opportunities to connect with others. Putnam’s detailed diagnosis could be addressed practically by directing people toward new patterns of social cohesion.

Christian accounts of loneliness initially took a divergent approach from the work of social scientists. Titles such as Loneliness and Spiritual Growth are representative. If Bowling Alone proposed that new patterns of social cohesion were needed to combat loneliness, works such as Loneliness and Spiritual Growth identified loneliness as a matter of the soul needing the opportunity to be comforted, affirmed, and encouraged. But this approach unwittingly reinforced the problems their secular counterparts understood too well: loneliness was not a matter of digging more into the self, but one of recognizing that perhaps we needed less time with ourselves.

To say that we live in a lonely age is, for the Christian, another way of saying that we live in the world.

But in recent years Christian reflection has taken a different tack and followed the lead of Putnam and company. The assumption now, found in innumerable books, is that Christianity describes humans as intrinsically communal, interconnected, and in need of true community. The theological claims here are relatively straightforward: the work of God on creation restores the image of God to humanity and, in doing so, breaks down the walls of division among people. Our corporate gathering as the church mirrors more closely what we are meant to be as people, and our presumption of being individuals first means only that loneliness will continue to tail us.

But it is worth asking whether this recent trend, of re-emphasizing Christian community, for all its importance, is prone to overpromising. Or more precisely: whether all of the resurgent talk about Christian community misunderstands its own role in the lives of lonely people. For it is one thing to claim (as I have in my recent book) that Christian community is a means by which God heals us of sin and draws us back into the life we have been created for. But it is another to say Christian community is that by which God rids our lives not only of sin but of the quiet desperation of loneliness as well.

Embracing Loneliness with the Saints

The difficulty is that discussions of Christian community still frequently operate under the assumption that the Christian life is best understood as the solution to a particular kind of problem—loneliness, in this case. This is, to be sure, not just a tendency seen in discussions around Christian community; the Christian life has at various times been saddled with promising stronger marriages, greater intellectual prowess, and increased happiness. But the assumption that Christian community is the solution to loneliness seems short-sighted, particularly if loneliness has not just cultural or sociological but also anthropological roots. What if loneliness is simply a condition of being human, whether Christian or otherwise?

To say that we live in a lonely age is, for the Christian, another way of saying that we live in the world. We live in a world created in grace but afflicted by sin, and so any account we offer of how human social life operates must account for both the grace of God and the burden of sin. We read stories of intimacy between humans and God in Eden, but from then on there are fractures and rifts even within the most devoted of families. But let us not lay the problem of loneliness at the feet of sin too quickly. What if it is not sin that creates loneliness, but simply being a creature of God after the fall?

And since the Christian life is lived in this world, Christian discussions of loneliness must broach the possibility that loneliness is intrinsic to our lives and not something Christian community can remove. Saying this is not a sign of defeat but a way of acknowledging that loneliness makes a home within the Christian life. This is a strange claim to make, but it is a claim that the saints, in their unguarded moments, are quite comfortable making. It is not so much that Christian community has failed when loneliness persists, but rather that Christian community offers us the kind of accompaniment that can help make sense of and bear loneliness without it turning into despair.

Christian community offers us the kind of accompaniment that can help make sense of and bear loneliness without it turning into despair.

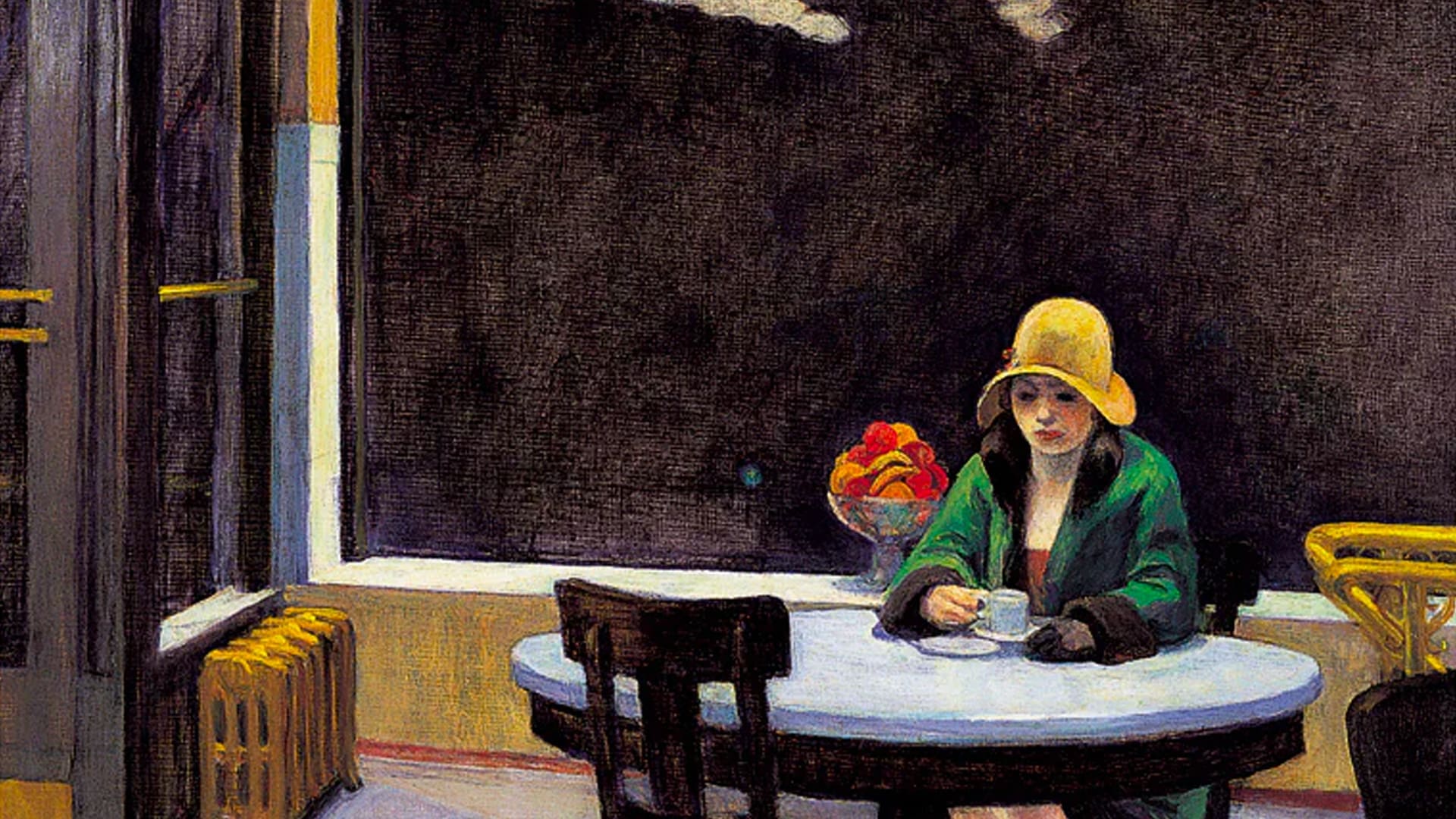

In her second autobiography, Dorothy Day famously described her own journey to faith as one that proceeded from partial happiness to the fullness of happiness, from a life devoted to social perfection to one devoted to a society made holy. She left behind her common-law marriage and many of her friends, establishing the Catholic Worker House in New York’s Bowery district along with Peter Maurin. She raised her daughter there in what we might now call an intentional community—that is, a community built on the monastic ideal and characterized by common meals, ministry, and times of teaching and discussion. “Community—that was the social answer to the long loneliness,” she writes.

When Day writes in the book’s postscript that “we have all known the long loneliness and we have learned that the only solution is love and that love comes with community,” we can miss the weight of her words. For those who have read her know that community life was full of disagreements, of daily frictions, of small victories against poverty and death amid great defeats. Within that same postscript, she writes that “at times [love] has been . . . a harsh and dreadful thing, and our very faith in love has been tried through fire.”

The very love that made community worth doing was also that which brought, for Day, deep agony with no abatement of the long loneliness—a phrase she used to describe the very act of living. “We cannot love God unless we love each other, and to love we must know each other,” she writes, but what she means here is precisely that the love we find in community is one that drags us through fire, not around it. The long loneliness was not banished by Christian community, for as she took up the life of the disciple, she learned that Christian community made it bearable. In the Christian community, one learned to pray, to bear burdens, and to hear the promises and pardon of God, even if that Christian community could not banish loneliness.

Consider the parallel witness of Henri Nouwen, for whom loneliness was the inalienable companion of the Christian life—even a prerequisite for a life with God. He distinguishes two types of loneliness—one rooted in anxiety for companionship and the other signifying God’s presence: “In the first loneliness, we are out of touch with God and experience ourselves as anxiously looking for someone or something that can give us a sense of belonging, intimacy, and home. The second loneliness comes from an intimacy with God that is deeper and greater than our feelings and thoughts can capture.” It is this second loneliness, he writes, that “we must be willing to embrace in love.”

Like Day, Nouwen approaches loneliness as an intrinsic feature of life before God. Discipleship will frequently take us to places we do not wish to go, even if we make that journey in the midst of Christian community. Embracing loneliness becomes a prerequisite to embracing the God who calls us to a frequently misunderstood and frustrating vocation.

When we treat Christian community as the antithesis of loneliness, we place a burden on Christian community it was never meant to bear.

To participate in a community and expect that loneliness will be absent is, for Nouwen, to misunderstand the nature of Christian community. Christian community does not exist to banish loneliness but rather to orient it toward solitude with God. If we do not embrace loneliness, we will constantly be preoccupied with our own pain and unable to attend to the pain of others or to receive the gifts they might give us. Loneliness invites us to see solitude with God as that which enables us to live for others. It is not gathering with others that ends our loneliness; rather, a life with others is possible only when we first befriend our loneliness, allowing it to point out the ways in which we hide from God, from our own woundedness, and from God’s calling to serve.

Nouwen sees a paradoxical yet real danger in refusing loneliness the ability to do its work: that we never find Christian community at all. Dietrich Bonhoeffer also draws out this insight in his book Life Together, where he demonstrates how loneliness, when banished, ultimately corrupts Christian community. When we treat Christian community as the antithesis of loneliness, we place a burden on Christian community it was never meant to bear. Division from one another may very well occur because we have sinned against one another, Bonhoeffer writes, but we must not expect that Christian community will somehow banish the conditions of being a creature in the world. The one unable to be alone, he writes, is the very one who should be wary of Christian community, for they will expect it to alleviate their loneliness in ways it is not meant to do.

The Persistence of Loneliness with God

If loneliness remains even in Christian community, what are we to say? The Psalms are rife with pleas for God to rescue us from despair, to restore us to friends and loved ones. And yet the form in which these prayers are answered is not, it seems, that the condition of loneliness goes away but that its pain is transformed. With Bonhoeffer, we see that loneliness is a precursor to solitude: if we are unable to bear with being alone, we will never be able to hear God in the days we spend apart from others. It is not that loneliness becomes less prevalent in our lives, but when it shows up, it shows up as a handmaiden, ushering us toward God and reminding us of the gifts of one another’s presence that we have when we are together.

Making sense of loneliness is an enduring feature of the lives of the modern saints. For Day, that loneliness becomes the cost of living into God’s kingdom—that we are known by God while misunderstood by the world and even our own compatriots. Likewise, for Nouwen, loneliness is the sign that we are approaching solitude with God, a state we embrace to be better able to minister to the pain of others. For Bonhoeffer, loneliness is the gift of being pulled out from the safety of a crowd that comes with cost of discipleship.

If the persistent loneliness of the world reminds us of the sin under which the world groans, then the loneliness of the saints is transfigured from a sign of spiritual starvation to a holy hunger. Loneliness is the pedagogue who helps us attend to the pain of others, driving us to listen more attentively to God’s voice. It is a mark of being human that reminds us of our need for God’s grace and companionship.

To feel lonely within the church is not a sign of the church’s deficiency but a strange gift: loneliness tells us that the community exists not for itself but for God, not to solve the problem of being a creature but to help us bear it well, and then to listen well to the pain of others.

To be called to Jesus is to embrace loneliness as a feature of the world that, by God’s grace, the Spirit makes use of: to make us attentive, to open our hands to suffering, to open our ears to God. The Christian community, as the body of Christ, is the company of others who cannot solve loneliness but must learn together to befriend it, that through it we might be led to God and to the sufferings of the world.