M

Most Western observers view Russia’s invasion of Ukraine as a purely geopolitical event, a tug-of-war between East and West, the powers of Europe and the aspirations of Russia. But it is also a war with deep religious roots, and it will have wide-ranging effects on people of all faiths in Ukraine. For centuries the Ukrainian Catholic Church has found itself under the strain of these warring pressures. Few people are better positioned to see these aspects, both religious and political, than Borys Gudziak, archbishop-metropolitan for the Ukrainian Catholic archeparchy of Philadelphia. Andrew Bennett, program director for religious freedom and the director of faith community engagement at Cardus, sat down to talk with about the many interrelated facets of the war, the spirit of the people who are defending their home, and the faith that sustains them.

—The editors

Andrew Bennett: Thank you, Your Grace, for taking the time to speak to Comment magazine about the war in Ukraine. You wear many hats, not only as the archbishop-metropolitan for the Ukrainian Catholic Archeparchy of Philadelphia, but also as the president of the Ukrainian Catholic University. You’ve got deep ties both in Ukraine and in the United States, and so we’re really grateful to get your perspective today.

Much of the political and media focus has been on the war as a geopolitical conflict, a war that is obviously exacting tremendous economic and above all human costs. But very little attention has been paid, outside religious circles, to the religious dimension of the war.

Could you shed a little bit of light for our readers on this religious dimension of the war in Ukraine?

Metropolitan Borys Gudziak: Well, the religious, spiritual dimension is crucially important. People don’t realize what is really striking them. I mean, what has brought Europe together? I was in Paris for seven years, from 2012 to 2019, and I saw how these postmodern, deconstructionist fissures were developing in European society. There is no common anthropology, and Europe is losing most or many common denominators in its social discourse.

Here in Washington, Democrats and Republicans are agreeing on something, however; and people of goodwill throughout the globe are really attentive. They’re aghast at the war, and they’re trying to help. Why? What’s behind that? Well, it’s not the military or even economic situation in an isolated way: This is a moral issue. It’s a spiritual thing.

And what has inspired them? It’s a question of good and evil. It’s really black and white, which we don’t want to admit. We don’t want to admit that something is really true and something is really wrong in an era of the dictatorship of subjectivity. People are seeing that Ukrainians are willing to give their lives for something, that David is standing up to Goliath, that an army that has one-tenth of the resources is holding its own against an aggressor, somebody that is killing indiscriminately not only soldiers but women and children, bombing not only military objects but homes and hospitals, churches and kindergartens.

And this moral aspect is speaking to the hearts of people. Ukraine has won this war morally. Morally, the war has been a clear issue and a clear victory. There still is a question of moral indignation and whether it leads to action, or whether people who are morally indignant will just be spectators spending endless hours watching CNN, Fox, or MSNBC, or whatever.

What we are seeing are examples of the greatest love that there is. Our Lord tells us—it’s recorded in the Gospel of John 15:13, if I’m not mistaken—there’s no greater love than when one gives one’s life for one’s friends. And we’re seeing that. People might not realize that is what is moving them, but they recognize that the greatest love is being witnessed, demonstrated, put into action against dark evil, a senseless killing.

We’re in Lent right now. We’re on a pilgrimage toward the resurrection, but there’s a crucifixion, and a real passion and crucifixion along the way. And in Lent, as we reflect on our sinfulness, we realize that Adam’s sin is what you might call a grab. Adam and Eve receive everything, but they grab for what will kill them. And they don’t live the gift. They don’t live the giftedness that they have received, and they don’t live in a giving way. That sin is the sin of our human nature. It’s the grab as opposed to the gift. And we see a ruthless, senseless, egotistical grab by a superpower armed to the teeth in nuclear weapons, but which has become morally vapid. And that encounter between the greatest love and the greatest evil, a killing evil, is really moving the world.

AB: I think it is especially striking even that our own postmodern elites who are typically shaped by a relativistic understanding of things can all of a sudden, when they encounter objective truth, find it very attractive. They see a nation of people and its leaders standing up to something that is objectively evil, and that’s very appealing.

You’ve talked about how the spiritual impact of the war is really at the heart of what is going on. What is it about the deep faith of the Ukrainian people, and in particular that faith born out of a history of suffering over certainly more than the last century, that leads to great virtue, that leads to sacrifice in the midst of great suffering? And how do we account for that to our Western observers, our Western elites, who may be experiencing a bit of an amnesia about why this is so crucial?

MBG: I’m not sure this expression of faith and love and sacrifice would happen elsewhere if other societies were faced by such adversity. But there are clear reasons why Ukrainians are prepared. I’m in Washington here, and people ask, “Why are the people in Ukraine not panicking? Why is the president acting with such resolution and courage? Why are the bishops in place? Yes, three million people left, but forty million people are still there.”

Ukrainians went through a hellacious twentieth century with about fifteen million people killed in different genocidal waves. They’ve gone through poverty. Their identity has been negated and denigrated. Putin put it all together in that speech on February 21. They realize that freedom is not free, that there is a cost for the most important principles and values in life. Actually, whether they explicitly confess it or not, they have a Paschal vision of life. It’s through carrying the cross that you reach life, real life, eternal life.

I think whether or not they’re going to church every day or for any services in any confession, they have a sense of communion. We saw it in each of the revolutions emerging in a way that also mystified the world in 2013 and 2014. Europeans were wondering, How could these people be dying with a European flag in their hands? Is the European Union worth something? Well, today Ukraine is giving meaning to the European Union, to European civilization.

And that, of course, is connected with its Paschal experience in living memory. All of the confessions were persecuted. The Ukrainian Catholic Church was completely illegal from 1946 to 1989. It was the biggest illegal church. There were thousands of martyrs. The Orthodox Church experienced severe martyrdom in the 1920s and ’30s in Ukraine and in Russia. There is not only a memory of that, but there’s a respect for it.

I know that the Ukrainian Catholic Church, which is maybe 8 or 9 percent of the population, has a public civic adherence in terms of its mission and its respect which is much greater, three times as great. Our church has also been articulating Catholic social doctrine in a very systematic way for thirty years. And if you look at the stance, the posture, the networking, and even some of the messages, it’s very clear that Catholic social doctrine is behind that.

But, of course, it’s not that Catholics invented the truth about social doctrine. This is God’s truth, and God’s truth, whether it’s through the Catholic Church or otherwise, is inscribed in people’s hearts and people discover that.

So it is actually in crises like these that we are pushed to set aside our idiocy—especially in the etymological sense of the word where we’re just focused on our idios, our own selves—and we start opening up. The spiritual life is always a question of communion, a relationship. It’s an openness to God. We Christians confess a God in three persons that is communion and love in the Godhead. There’s the giving of the Father to the Son and the Holy Spirit. That communion is what people are experiencing. They’re helping each other. The isolation, the alienation drops because people need the communion to survive, and they find, then, that communion is really the truth. It’s not just a coping mechanism.

AB: When I was in Lviv back in October of 2014, just after the annexation of Crimea by Russia and the beginning of the invasion into the Donbass, I met with a number of seminarians at the major seminary in Lviv. We were talking about the Maidan Revolution, which was, as you know, christened the Revolution of Dignity, of human dignity. I remember one of the seminarians asked me, “Are we doing the right thing?” I was so struck by the question, at both the humility of it and the vocational essence of it.

So what would you say is Ukraine’s vocation right now?

MBG: Well, in one sense, it’s sometimes dangerous to have an auto-messianic view, where you see in yourselves, in those that are of your tribe, a unique messianic vision. But the fact of the matter is, we all have a vocation, and our vocation has fundamental commonality. It’s a vocation to live in communion with God and neighbour, to love God and neighbour, to serve, to uplift, to be mutually life-giving. That, I think, is the call for every human being in every culture.

In Ukraine today, there is a very clear vocation to witness in a social, political, spiritual way, also in a practical military way: the defence of the innocents, the proclamation of the kingdom in the face of the darkness, to carry the light into and through a tunnel, to conquer fear, to be willing to sacrifice and make the ultimate sacrifice for the most important things and for the most important people. And the most important people are the others. “When we lose ourselves,” Jesus says, “we find ourselves. When the seed dies, it gives fruit.”

So there’s a very specific way in which Ukrainians in general, and each Ukrainian individually today, are called to respond to this death-carrying evil, this movement, ideology, social and political system of authoritarianism that wants to snuff out freedom and God-given human dignity. And we see that happening before our eyes. And because it is so true, it is so inspiring.

AB: One last question about the vocation of those of us who desire solidarity with Ukraine, who feel the urge to do something. So often in the Western world, we always want to be fully in control. And I think the desire to help Ukraine comes out of a desire to help things be controlled. But so often there is much we simply cannot do. One thing that I’ve been recommending to people in Canada who ask me what they can do—besides obviously prayer, supportive relief efforts, care for refugees as they come out of Ukraine—is to speak the truth and ensure that the truth is proclaimed in the streets here in Canada. How crucial is that in this circumstance?

MBG: The three things our church explicitly set as our vocation in this crisis a month ago are to pray, to inform, and to help. There is a lot of disinformation. There are a lot of lies out there. The lies are specific lies like the minister of foreign affairs, Sergey Lavrov, a few days ago in Istanbul saying, “We didn’t invade Ukraine. We’re not invading.” Or the general lie, which is becoming law in Russia, “It’s not a war, it’s a special operation.” Or, “We’re working against the Nazis led by a Jewish president.”

They’re very specific lies, but there’s the deep lie of the system, the corruption, the oligarchic kleptocracy that is led by an authoritarian ruler who has nostalgia for empire and wants to recolonize. That’s a lie because it very explicitly negates the value, the dignity of other persons, other cultures, other histories.

So, calling that out, speaking to it, pointing out where it is not true by saying the truth not only is liberating but also becomes a guide for our posture, our relationships, what we do and what we say. And people can do and say the wrong thing. People can be very mistaken at the highest level, the most educated people. The past four or three presidents, twenty-first-century presidents, are all Ivy League school graduates: Bush, Obama, and Trump. They were very wrong.

Bush looked into the soul, as he said, of Vladimir Putin in 2000 and saw a straightforward and trustworthy man. He had no idea what it means to be a KGB agent, what kind of moral move was made by Putin as young man. And how, for now half a century, he’s been reinforcing that fundamental moral option that he made for evil, for repression, for a cynical system.

Barack Obama ridiculed Mitt Romney during a presidential debate in 2012, when Romney, recognizing many of these things, said that Russia is the United States’ greatest geopolitical challenge. Obama ridiculed it eighteen months before Russia attacked Ukraine and occupied the Donbass and annexed Crimea.

President Trump has been so complimentary of President Putin. He’s the only politician of significance, of international stature, that Trump has not criticized or demeaned. And two days after the invasion, Trump called it an act of genius because he sees in Putin somebody who is strong, who goes after his goals, giving no thought to the fact that his goals are evil.

So the top leaders of the strongest country in the world, of which I am a citizen, made fundamental mistakes. Today the prime minister of the United Kingdom, Boris Johnson, said we made a terrible mistake in 2014. We did not understand. “The denial of truth, the ignorance of the truth in these and all matters, leads to terrible mistakes,” in the words of Boris Johnson, “and terrible suffering.” The truth is very important.

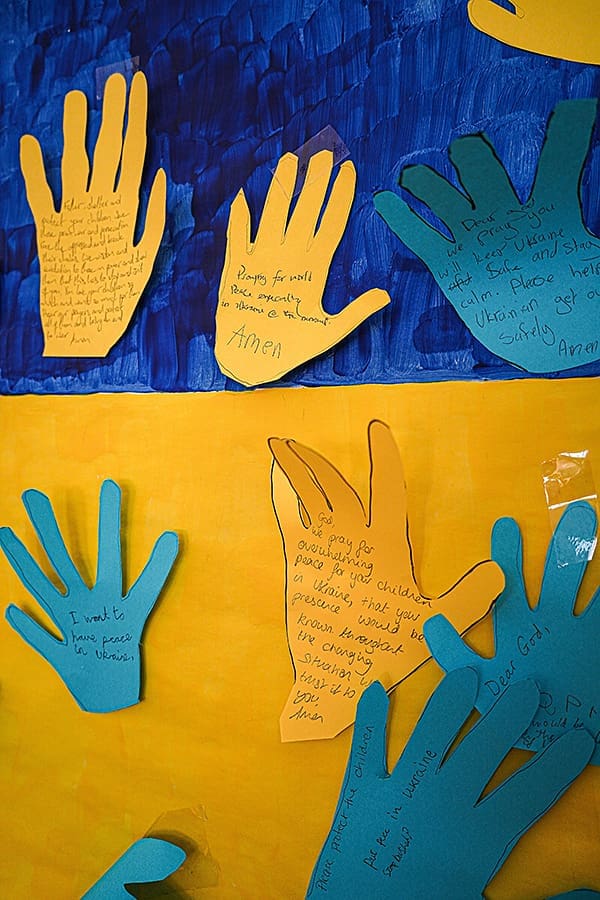

Prayers for Ukraine in the Well Church in Sheffield, UK. Image: Benjamin Elliot

AB: Any last thoughts you’d like to offer our readers on the war in Ukraine and what we’ve been discussing, Your Grace?

MBG: Well, I’d like to say that Ukrainians are very grateful for the global solidarity. We’re glad that Ukraine is becoming a donor for Europe, that it’s bringing together a continent that has had increasing fragmentation and fissures, that it’s served to bring the North Atlantic community together, that it’s inspiring people.

We want to encourage people. Don’t just sit there in front of the TV, but defend Ukraine. Defend the innocent, the children, the women, the maternity hospitals that are being bombed. Point out to your politicians that they’re behind the times. They made a terrible mistake in 2014, whether it’s in the US or Canada or Europe, but it’s not too late to do the right thing now.

For people of faith, it’s important to realize that a Russian occupation will lead to the suppression of faith communities. We saw the sacred ground of Babi Yar hit by a missile and five people were killed there. We see how in the last eight years the Muslim Tatars have been persecuted. We see in this country where there’s a Jewish president how the Christian, Jewish, and Muslim communities have come together in the Ukrainian Council of Churches and Religious Organizations, because they realize that what is happening now will lead to what has happened in the past. In 2014 two Protestant deacons—two sons of a clergyman—were pulled out of a church and executed. In the last few days three Orthodox priests were killed.

Every time the Russian regime—tsarist, Communist, or Putinist—takes over any part of Ukrainian territory where the Ukrainian Catholic Church ministers, the church is strangled. It might take a year or two, it might take a decade or two, but sooner or later it happens. And hearkening back to the Russian imperial and Communist legacy, Putin will do the same. He’ll crush the Ukrainian Orthodox Church as the Russian Communists did in the 1920s and ’30s. Nobody is safe in autocracy. Nobody is safe in a system of lies.

Conservative Christians and others should be disabused of the illusion that Putin defends traditional values. Russia has the highest abortion rate in the world, astronomic alcoholism, suicide, and divorce rates. The system is thoroughly corrupt. This is what Ukrainians don’t want. This is what they’re standing up against. They’re fighting this war for Europe, for the Eurasian countries. They’re fighting it for the freedom that North Americans enjoy, freedoms that come into jeopardy if they’re not defended. And that is why global solidarity is so important. Global communion and global coming together around the truth.

AB: Thank you, Your Grace. Maybe can we finish by you offering a prayer that our readers can take with them as they go?

MBG: May the Lord protect the protectors of the truth. May he guide the leaders of the world to have courage and to act. May the widows, the orphans, the refugees be offered solace and support by the world. And may Almighty God bless Ukraine and all those who defend the truth and make sacrifices for their brothers and sisters. Amen.

AB: Amen.