T

To an astonishing degree, modern thought ever since Marcel Mauss (with respect to society) and Martin Heidegger (with respect to being) has posed the question of the gift. Is the gift everything? Is it the one source of power, justice, and order, in terms of both human social existence and ontological reality? In effect, it has been asked whether gift should be raised to the status of a transcendental, like truth, goodness, beauty, unity, and being itself.

If that is the case, then it becomes tempting to see gift as the mediator between relatively impersonal transcendental terms like “truth” and more personal ones such as “grace” and “love” that have been associated with a personal and transcendent God.

Mauss in fact declared, in his short but revolutionary book Le Don (translated as The Gift), that he was not even sure whether he was talking about the gift or about something else. That is because he was really trying to talk about everything, at least as regards human existence.

Positivism

Mauss was above all a sociologist, in the tradition of his uncle Émile Durkheim and the founder of sociology, Auguste Comte. Comte was also the founder of positivism, a tradition Durkheim reworked but did not simply abandon. The social, in positivist terms, meant above all a given factual and positive organic whole that explains everything else that lies within its scope. The social cannot be further explained in speculative, “metaphysical” terms. Its holistic givenness is rather the explanation of everything else in human culture.

As a result, the “social” tends to displace “God” in the mode of a new and secular religiosity. Indeed, Comte, himself on the political right, had in a sense simply inverted Catholic “traditionalists” like Louis de Bonald, for whom society was literally a divine revelation. To be within the social was to be within an order that belongs already inside the divine mind and is divinely sustained rather than humanly and historically constructed. In Comte’s inversion of this scheme, no longer is society alienated to the realm of God. Instead, it is the sacrality of the social that is the secret of all religion—that is, when it has been demythologized. The immanence, fetishism, and animism of primitive religion was thus in a sense nearer to this view than the later age of transcendence and metaphysical illusion. In the positive, modern epoch, the full “social” truth can finally come into its own.

Mauss, like his uncle, continued to insist that “the social” was its own factual dimension, which a strict science could discover and describe: something fully belonging to the natural order and not something posited by metaphysics or even philosophy.

As with Durkheim, Mauss pitted the primacy of the social against both the primacy of the economic and the primacy of the political.

In the former case, he questioned the assumption of the supposedly self-interested and utilitarian economic actor. Teleological motivation cannot be assumed a priori, Durkheim had argued; science must rather infer the direction of human purpose from a close examination of the actual facts, which turn out not universally to support the primacy of Homo economicus. In the latter case, Durkheim doubted the assumption that people first of all come together as individuals through deliberate political arrangements. Rather, they are earlier found in families, tribes, secret societies, and local communities—which may, however, be of geographically wide extent.

For Mauss, empirical and genealogical evidence is necessary in order to show that what we take to be “natural” notions of, say, economy, contract, personhood, physical posture, and prayer—along with our assumed divisions between the economic, the legal, the political, and the religious—are not natural at all, but socially constructed and variable. And yet his ultimate purpose is not relativistic. For he takes the facts on which he focuses to be uniquely symptomatic: facts that in microcosm reveal the entire shared secret of a particular society.

And not just of that particular society: somehow also of society as such across the ages. Thus, for example, it is for Mauss as if the great variety of attested marriage customs still reveal something about the essence of marriage in itself. By combining them, we can get a better grasp of the general social phenomenon of marriage and ways in which it might be reformed. Related to this overwhelming search for the unified social source of power, justice, and order are both Mauss’s sense of very long-term genealogical continuities and his sense of very widespread geographical connections. Not only did he conjecture that the Pacific had for long ages constituted a single cultural sphere; he also thought that in the American Northwest one could catch a glimpse of what primitive China must have once been like. Humanity, for Mauss, remained almost Adamically and monogenically one.

The Gift

All these things come to a head with respect to the gift. The gift, for Mauss, is the supreme “total social fact.” He takes a seemingly marginal social phenomenon, the giving of gifts, and shows that it is not just symptomatic of the human in general, but supremely so. According to Mauss, the social bond itself, the very source of all power, justice, and order, is the triple imperative to give, to receive, and to return. He is not really arguing that this is metaphysically explicable: as a positivist he is saying that it is just mysteriously there as a matter of universal fact. It is, however, a fact that is also an imperative, an “is” that is also an “ought.” Rather than something to be explained, it explains everything else.

According to Mauss, the social bond itself, the very source of all power, justice, and order, is the triple imperative to give, to receive, and to return.

The gift, therefore, was Mauss’s ultimate sociological offering. But does it not rather deconstruct the very bounds of sociology? We can see this in four distinct ways.

First, in contrast to Durkheim, the model of circulation implied by gift-exchange disallows any idea that the social exerts pressure on individuals from without. Instead, it is individuals who somehow shape the very social realities by which they are also compelled. When we freely give, we also sense an obligation to charity that comes not just from the logic of our own freedom but also from the specific other person, from the intersubjective social order, and from its sacral normativity: an obligation that presses on us rather like a social subconscious. It is as if every time a person acts (which is in some sense to give), the social order is hidden and in suspense, and yet she is bound to reaffirm it by her performance.

This means that historical action and behaviour are not just subordinate to an ahistorical social order. Neither is the social prior to the ethical, with the ethical consequently reduced to the functional in relation to the social order. Instead, if the social order has to be constantly reaffirmed through performance, it exists at all only in relation to the imperative of value. If we see value as objective, and also as natural and relational, then the social is there as something we have to reckon with.

Gift-exchange, then, is the pivotal social fact because it most of all exhibits the social as the cultural extra that distinguishes human from animal. We exchange gifts in order to be fully human, and yet we can possess this quality only voluntarily and serially.

Second, the gift no longer “represents” a given social order that precedes it and requires it. Instead, it expresses a social order that exists only through the gift’s very expression. As a result, the social, if it remains natural, ceases to be something pre-cultural and pre-linguistic. A gift is a gift only because it is a valued thing and therefore symbolic of mutuality as such—both particular and universal.

A gift is only a gift because it is a valued thing and therefore symbolic of mutuality.

Third, Mauss spoke affirmatively of evolution from gift to contract, from collective to individual personhood, to the distinction between person and thing, and of law from economy. He does not, moreover, attribute these shifts to the political and economic pressures of greater territories of control and distances of trade (explanations that new archaeological evidence today renders more implausible) but sees them more sociologically in terms of a naturally emergent complexification. Yet he clearly did not see this process as simply a unidirectional advance into natural and inevitable progress away from primitive “mechanical” confusion, as Durkheim did. For him, something has been lost and something forgotten that yet lurks in our social, linguistic, and individual subconscious. Ultimately, our specialized social creativity today withers because of this forgetting of a deeper linkage and continuity.

Thus, if the gift might be seen as a kind of primitive, ornamented contract, then equally the gift, which requires trust and a ceaseless personal renewing of goodwill if its formality is to hold, haunts the modern contract. Indeed, as later followers of Mauss have pointed out, it may be more logical to read contractual exchange as a mode of gift-giving than the other way around (which arbitrarily assumes a natural human selfishness) because a monetary payment is a sign of promise that permits the recipient eventually to receive concrete things in return, according to a convention of social circulation supported by the law, which is ultimately linked to wider solidarities.

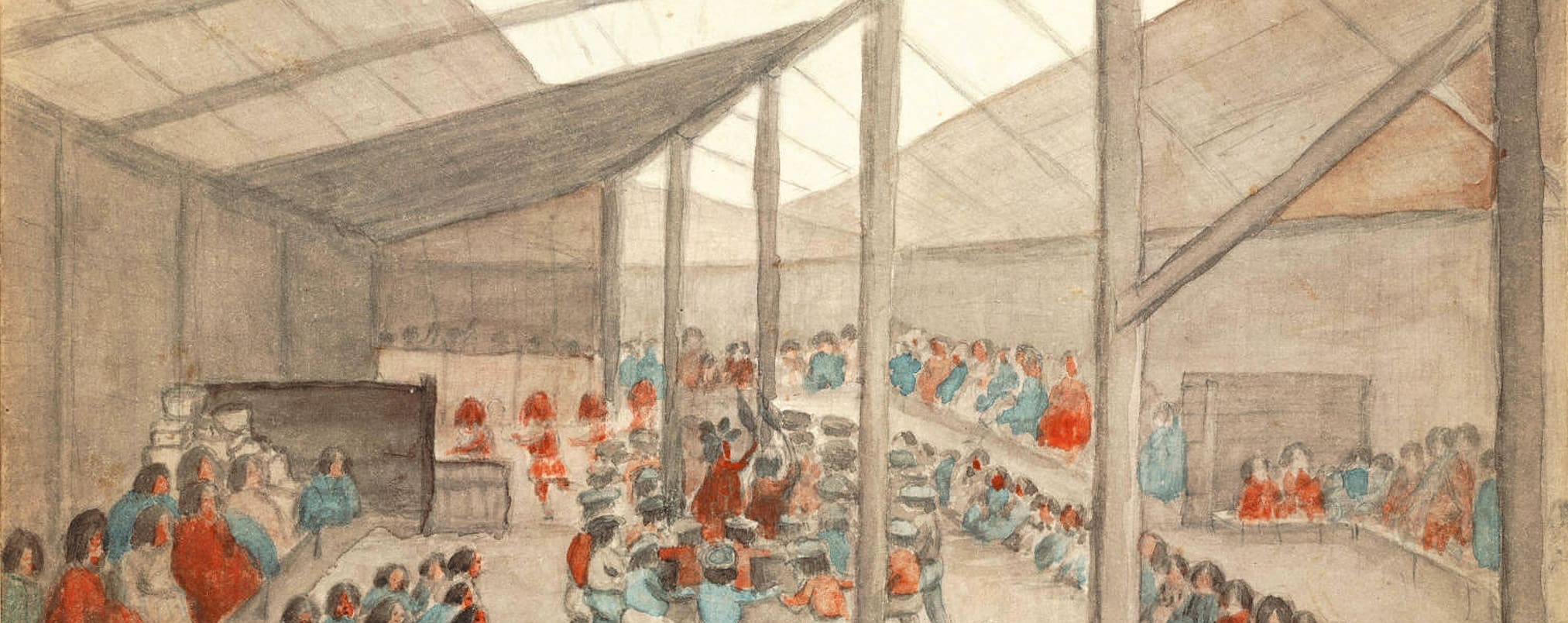

It is actually the very joining together of interest and disinterest and of the interpersonal with the social totality in early human societies that allows interest and personhood to be more singled out in later societies. But this development, Mauss says, has resulted in an imbalance: we have lost sight of contract’s roots in mutual generosity, along with the basis of individual identity in public naming and recognition. Thus, Mauss concludes The Gift with an appeal to restore to some degree the primitive sense of constitutive festivity and of a general (not restricted and disembedded) economy. In such an economy, goods are exchanged for the sake of symbolic expression and not mere convenience. In practical political terms, this concerns the role of cooperatives, politically purposed and recognized corporations, and schemes of welfare insurance. It is for Mauss a “sociological” politics—ending the complete divisions of the legal, economic, and political—that has the capacity to restore politics in the Socratic sense as a continuous self-ruling of citizens (in a mixture of hierarchic and egalitarian formations), as he declares in the final sentence of The Gift.

In the fourth place, Mauss’s perspective no longer really allows the reduction of the religious to the social, because the social just is unfathomably religious. Gift-exchanges take place between individuals and groups who represent transcendent divine forces, sometimes, as especially in the American Northwest, by donning masks, which are the original personae. For this reason, human beings are sacrally compelled, as if they were simply passive participants. Inversely, things as gifts are somewhat personified; they share in the identity of the givers and so must in some mode return to them. This is because the obligation to circulate involves the more than human. All this assumes a metaphysical framework of both horizontal and vertical participation. The obligation toward mutual assistance and care extends to natural things besides human persons and is underwritten by divine forces to whom both things and persons are linked by the more ultimate bonds of offering—namely, sacrifice.

Every later critical questioning of Mauss involves a denial that the gift can be both social and transcendent in this way, whether made in the name of a reductive sociology, structural or post-structural linguistics, liberal politics, or Marxist economics.

Alain Testart, for instance, has imposed an anachronistically liberal and modern typology onto primitive peoples, insisting that we can distinguish the purely “free” and usually merely symbolic gift from various modes of enforceable exchange and taxation. But for Mauss the social as such involves a mysterious mixture of the obligatory with the freely creative, such that even what one “has” to carry out can still be carried out as a free gesture.

Mauss did not deny that it was possible to make these distinctions, nor did he necessarily condemn them. His point was that all these things are ultimately linked in terms of a deeper shared logic, and that some social phenomena reveal this linkage to us more than others: above all the “total prestation”—that is, the continuous exchange of everything all the time—which he supposed the very earliest societies had exemplified.

Mauss’s own religious views remain unclear, but he indicated that they were influenced somewhat by Spinoza. He was possibly inclined to think that the order of everything whatsoever has both a physical and a meaningful aspect, and he certainly saw “the social” as close to the divine.

Modern individuality as we now conceive of it did not exist in the far past. It has for Mauss evolved, by way of Greece and Rome, from the need in certain societies for several operators to don the masks of single divine forces. Just as gift has naturally become contract but secretly remains gift, so also mask has become person but secretly remains mask. And just as gift and contract appear to be opposites but are not so, so also unity and individual personhood appear to be opposites but are not so: “It is from the notion of the ‘one’ that the notion of the personne was created.” Remarkably, Mauss declared that it is the trinitarian and christological formulations that grasp the linkage of these apparent opposites. He suggested that it is these formulations that have most shaped our modern sense of the person, both divine and human, and that they should continue to do so.

For Mauss the ultimate is relational, and yet it is also monistic, just as gift-exchange is free and variously appropriate as between different persons.

Order and Justice

What Mauss offers us, then, in terms of his vision of social order is neither a crude progressivism nor a simplistic primitivism in the lineage of Rousseau. He in effect anticipated recent archaeological discoveries which show that prehistoric communities of order might have been geographically extensive and interlinked, even comprising what appear to be vast cities. Yet, unlike anarchist theorists such as David Graeber and David Wengrow, he did not anachronistically see a supposed primitive will to negative liberty (to disobey, to flee, and to shape de novo) as more basic than a primitive love of social regularity and security. If he demanded a return of primitive wisdom in order to balance out our excessive fissiparousness, then he knew that this was to invoke a certain religiosity, with its “atmosphere” of restrained festivity, of joyful but dignified ritual, of the promotion of symbolic expenditure over accumulation.

And when he wished to characterize this balance, it is significant that he appealed to the axial religions and notably to both Islam and Christianity. For him, they seemed to combine a celebration of social unity with a celebration of social or varied role-performing individuality.

On questions of philosophy and metaphysics, Mauss retained an agnostic silence. Yet his own post-sociological conclusions would seem to demand something to be said in that respect. If gift is fundamental to human existence and includes our relationship with nature, then we have to see ourselves individually and collectively as entirely gift, compelled to a total and continuous existential gratitude and return offering.

For if, alternatively, reality is merely society or physical nature, then what lies beyond mere interest is without reason or of any human concern. In order for that which is ultimate and done for its own sake to be able to command our concern and our interest, it must involve the gesture of generosity. And that generosity must be mutually sustained.

It follows that, to have any ultimate human purpose, we must generously promote the order of gift, which is also the true order of exchange. And if we do not take this horizontal participation in things and other people as also a vertical participation in an eternal and sacral exchange, then we implicitly consign all imagined order and justice to the realm of an illusion that conceals the hidden operation of sheerly impersonal powers.

It is true that Mauss freely allowed that the gift was bound up with fiction, pretence, and secrecy, besides magical “left-handedness” and hermetic fraternities, just as tribal initiations sometimes reveal to the initiated that the terrifying howls of supposed gods are really the howls of men. Yet his deeper point was that if there are to be men or human beings at all, then the howls are also after all taken to be the voices of the gods—voices that demand our celebration of all that we have been given, through a continuous performance of sacral and festive generosity, if we are to continue to “speak human.”

It is the “extra” to nature that turns out curiously to be natural. Forgetting the joyous and crazy original superfluity of grace, we have inevitably turned our over-seriousness toward destruction of ourselves and of the planet, since the ultimate alienation of thing from person and of person from person is founded on individual and unlimited domination of both the one and the other.

The spirit of the gift instead recalls us to the unnecessary mirth of conviviality if we are once more to ensure for both nature and civilization even the basic necessities for survival.