M

Many of us have acquired the strange habit of talking about friendship as love’s rival. To be just friends, or placed in the friend zone, is to be relegated to a lesser relationship status. Friendship, in the contemporary imagination, differs from romantic love by degree of intimacy, or perhaps even in quality.

Once you start looking at the many analogies between friendship and its erotic counterpart, this zero-sum understanding seems a mistake. Consider the origins of each love. Despite friendship’s absence of sexual desire—at least as an essential component—its beginnings seem to mirror what it is like to fall in love. Lasting friendships, after all, usually overtake you long before your intentions or desires are clear. A strange alchemy attracts you to this person and not another, and if the attachment is strong enough, you may even find yourself losing all sense of time when discussing topics of common obsession or pursuing activities that you both find endlessly enjoyable.

I could do a self-inventory of my friends—the stages of life in which I gained them, the transitory hobbies and interests that brought us together for a time, and the ways in which we drifted apart and, in some instances, found each other again. In most cases, there was no single moment, no conversion experience, in which the person shifted ontologically from acquaintance to friend. It was a slow dawning—a retrospective delight—once I realized how close we had become. No one had to sign terms of agreement to enter into the arrangement; things emerged organically, with no anticipation.

So, at first glance, friendship seems to be as organic and unplanned as romantic love. And yet, when you fall in love romantically, there is a common road map of emotional destinations: going exclusive, saying I love you for the first time, meeting the parents, engagement, and vowed commitment to each other. There is no analogous road map for friendship. Once you’ve fallen into friendship, what then? Romance and marriage carry with them personal, social, and perhaps theological norms that are designed to protect the relationship and make expectations clear. Friendship—at least to us moderns—lacks such norms and intentionality. Does this lack of structure and intentionality imply a nonchalance about modern friendship? Amid all the competing obligations of modern life, are we prepared for the vulnerability that genuine friendship must entail? And how can we commit to forms of intimacy that we expect to change us in fundamental ways?

The Intentions of Friendship

Right after my first terrifyingly insecure year in graduate school, an acquaintance, Wes, reached out to thank me for something I had written in appreciation of his own work. We exchanged several emails, and in one he mentioned reading the memoir of the theologian Stanley Hauerwas, Hannah’s Child. Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the book, to both of us, it turned out, was Hauerwas’s description of a series of meaningful friendships with his fellow academics—scholars whom Wes and I admired and about whom we were eager for all the gossip. Wes proposed that we try out what he called an “academic friendship” of our own, modelled after Hauerwas. He acknowledged that it might involve a discernible time commitment, and I was under no obligation to say yes. But would I be interested in exchanging some scholarly work to keep the conversation going?

In my recollection, we did exchange some scholarship-in-progress, but the lion’s share of the relationship was the discussion of mutual connections and prospective interests. Oh, if you like this author (as I do), you should read this one as well. Shared misery or at least insecurity was another ironic delight: facing a horrendous academic job market, or worrying about getting admitted to a top-tier doctoral program, created space for mutual recognition that was not available with just anyone.

The intentionality of my new academic friendship was rare, and having a friendship proposed to me was decidedly novel. It was almost as if we signed on the dotted line or contracted to do the things constitutive of friendship among (at that time) prospective scholars. Perhaps this arrangement seems odd in a modern context, given how friendships now seem like a matter of happenstance. But the intentional and contractual aspect of friendship was hardly foreign in earlier times.

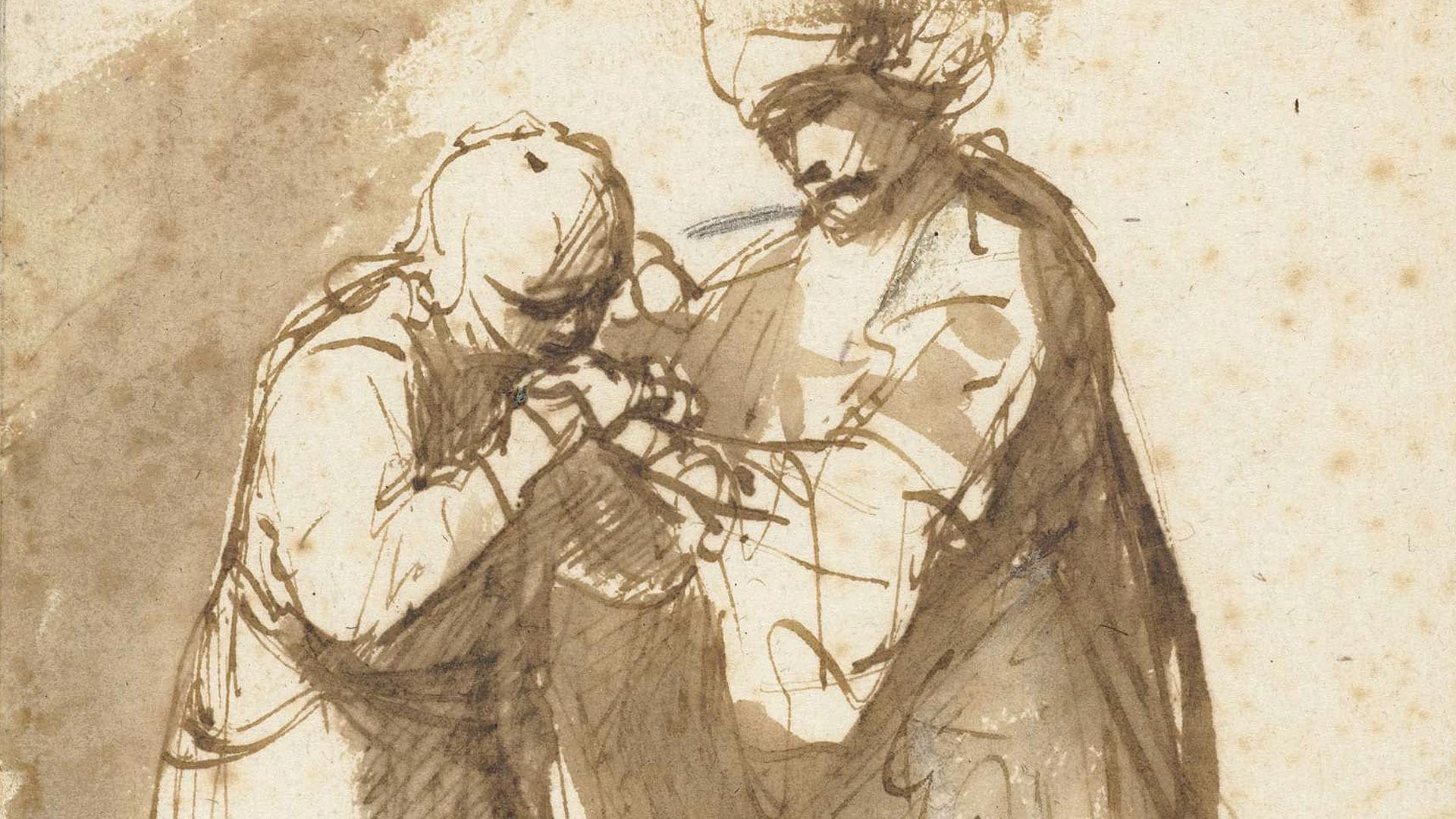

One of my favourite early moderns is the obscure Calvinist theologian Lambert Daneau. Like many Renaissance- and Reformation-era thinkers, Daneau was a polyglot with astonishing interdisciplinary expertise. Some of his better-known works include a treatise on modern physics and another on witchcraft. (For the record, he was a proponent of the former, not the latter.) My own favourite treatise is his brief work on friendship. A deeply systematic thinker, Daneau never met a definition he couldn’t parse to death. His approach to friendship was no different. He dutifully cites all the usual suspects—Aristotle, Cicero, and an assortment of their Christian stepchildren—while triangulating the precise nature of friendship. Strikingly, however, he proposes the biblical relationship between David and Jonathan as the paradigm for true Christian friendship. And he highlights a unique feature of David and Jonathan’s relationship as distinctive: their covenant to be friends with each other.

The soul of Jonathan was knit to the soul of David, and Jonathan loved him as his own soul. . . . Then Jonathan made a covenant with David, because he loved him as his own soul. And Jonathan stripped himself of the robe that was on him and gave it to David, and his armor, and even his sword and his bow and his belt. (1 Samuel 18:1, 3–4)

Daneau notes that the public nature of the covenant between Jonathan and David provides dramatic tension for subsequent chapters in the biblical narrative. The loyalty of these two friends overrides Jonathan’s filial and political obligations to his royal father, Saul. And Saul, ever the jealous narcissist, attempts to manipulate Jonathan and the royal household in his zeal to murder David, whom he views as a threat to his kingly office. Jonathan’s “ardent affection” for David overcomes all these competing relational obligations, and he manages to save David from his father’s wrath, before tragically dying in battle. The tragic pathos of Achilles and Patroclus has nothing on the Hebrew Bible.

The more intimate the friendship, the more permeable we become to the Other Self, loving what they love because they love it.

The idea of covenanted relationships ran deep in Daneau’s Reformed Protestant world. The gist of Daneau’s application of the biblical idea of covenant to human friendships is that there is some mutual agreement between parties to love each other and to seek union with each other. Importantly, the fruits of this covenantal relationship must be concrete enough for others to notice, often through symbolic exchange—as with Jonathan’s gifts to David in the narrative above. David literally wore his relationship with Jonathan on his body. Friendship involves a public commitment to do what good friends do: to seek the welfare of the beloved, defend him from his enemies, share in his joys, and encourage him in virtue and piety. Friendship is a matter of deadly earnest. Like its marital counterpart, friendship exists between “faithful vowed lovers,” says Daneau. The covenantal vow ensures an almost sacral value of the relationship. Notably, the vow of friendship has the double effect of posing a potential threat to other social or political obligations, as with Jonathan’s compromised relationship with his father, who happened to be the king. Friendship is a site for political resistance—a fact recognized not only by the biblical author of 1 Samuel but also in a locus classicus in Cicero’s De Amicitia.

Taking account of all these features, I doubt Daneau would have recognized my academic relationship with Wes as true Christian friendship. True, my colleague and I had a measure of commitment, participated in a sort of symbolic exchange of (scholarly) goods, and were intentional about commencing the relationship. We did venture something, even if no solemn covenant was made. We did make a decision to do what good friends do. And if one partner in the relationship failed to reciprocate in these matters, the friendship ceased to be—for a time, at least. However, no vows were taken, and so no public disgrace resulted when we drifted apart for some years. But could anyone’s friendship measure up to these standards?

The Vulnerabilities of Friendship

I occasionally teach Montaigne’s essay “On Friendship” to undergraduates. Despite some notable differences from ancient and medieval models of friendship, Montaigne’s essay evokes the same intensity as anything Aristotle or Cicero or Daneau could offer. There is an almost metaphysical union between Montaigne and his beloved friend La Boétie. Theirs is a “friendship that possesses the soul.” While the two did not exchange physical gifts as a pledge, Montaigne gives himself in the friendship: “Rather than drawing the one I love to me I give myself to him.”

Once, after hearing this line, one of the students sitting in the back row of class piped up: If Montaigne really thought his beloved friend was all that, he should really have put a ring on it.

It was a juvenile joke, but my student’s comment underscored a significant fact: our only remaining framework for understanding this level of commitment to another human being is probably marriage. The marriage ceremony itself has remained surprisingly impervious to modern innovations, in most cases. We still assume that the long-term union of lovers is something risky and important enough to merit public recognition and accountability. We still have the couple recite vows to each other. We generally expect the couple to exchange rings as a pledge of their troth. And we still expect each person to yield the relational goods promised in the ceremony until death—or divorce—do they part.

My undergraduate students do not think that these practices, in the context of romantic love, are strange. They do think Montaigne’s description of his friendship with La Boétie—not to mention the biblical narrative of Jonathan and David—is a bit extra. Solemn commitment seems to pertain to eros, not philia.

Why are we comfortable thinking this way about romantic relationships but not friendships? Biology seems relevant on some level. Sexual desire, or in many cases the desire to protect a sexual relationship, nudges us toward serious, public commitment. This motivation—which we might call the if you like it, then you should have put a ring on it factor—is helpful to explain other types of long-term relationships as well. For instance, the exchange of rings in a marriage ceremony is analogous to the role of a surety bond in a commercial venture. Both are relationships deemed valuable enough to merit the risk and the legal commitment. Show your partner that you have some skin in the game, that these promises are not empty words. And make yourself vulnerable to some public approbation and financial loss should you flake out or prove unfaithful.

Both romantic and commercial ventures are often recognized as promising and desirable but also vulnerable. Modern marriages and business partnerships are hardly indissoluble, and no wise soul enters into something so serious without some trepidation about impermanence. So again, we should ask, Why not friendship? Doesn’t friendship, too, involve serious commitment? Don’t friends make themselves vulnerable to each other? Isn’t friendship—like marriage or business partnerships—susceptible to betrayal, flakiness, and inconstancy? If so, why don’t we approach it with the same seriousness and intentionality that we do other long-term relationships?

It is common to hear the argument that social media and digital communities have undermined our capacity for friendship, or that the modern pace of life mounts formidable obstacles to forming truly intimate bonds, such as existed between Montaigne and La Boétie, or David and Jonathan. I am inclined to think that these narratives carry some truth, but I also suspect that there is something else more fundamentally askew. Intimate friendship entails an intentionality and vulnerability. How many of us, amid all our competing social and emotional commitments, are prepared to undertake such a risky venture?

Committing to Friendship

The offer of friendship, especially in its early days, entails the risk of rejection or abandonment. Your initial investment of time and attention may not be returned. When Wes suggested friendship to me, a thousand insecurities could have aborted the fledgling relationship. A thousand personal distractions or rival professional relationships could have consumed either of us, stalling our conversations indefinitely.

Often, even the most promising friendships fail because of the threat they pose to our sense of self. Relationships between co-workers, colleagues, and comrades are relatively easy to maintain through shared interests, pursuits, and even common enemies. Intimate friendships, however, invite us to consider taking on new interests, pursuits, and, yes, even enemies. Any real friendship worth having is worth venturing your own self. The more intimate the friendship, the more permeable we become to the Other Self, loving what they love because they love it.

The philosopher Alexander Nehamas says—rightly, I think—that commencing a genuine friendship requires us to surrender our future selves to the relationship. It carries the implication that “other things about us, things we don’t yet know—even things that may come into existence only because of our friendship—will seem attractive to us as we come to know each other better.” It is a lovely sentiment, but also vaguely discomfiting. If in the early days of a relationship we knew all the ways that a particularly intimate friendship would change us, how it might transfigure some of our core values, we would be excused for being a little bit reluctant to jump in. How many of us are ready to surrender ourselves to someone in advance of truly knowing them—if that were ever possible? What if the defining feature of friendship lies not in receiving permission to be ourselves but rather in opening ourselves to loving what the beloved friend loves and cultivating those mutual loves alongside her? What would this entail? Certainly more than many of us can comprehend in the early days of a relationship.

The deeper the friendship, the more entangled we become in the beloved’s attitudes and habits.

But this is true of any meaningful relationship. When I think of myself over a decade ago, brazenly deciding I was ready to be a father, could I have known the sacrifices, the heartbreak, the radical shifts in attitudes and habits that my sons and daughter would cause in me? If I had known that a decade into fatherhood I would be raising them for a time as a single divorced parent—with all the challenges that would pose for them as well as for me—would I have so blithely committed myself to that future?

In retrospect, yes, of course—with some regrets but no qualifications. Paternal love is properly immeasurable, as I’ve come to experience it, and no personal expense or emotional wounds can lessen its hold on you. But, sight unseen, this all would have been—and should have been—terrifying to that earlier version of myself.

Any friendship worth its name is no different. The deeper the friendship, the more entangled we become in the beloved’s attitudes and habits. We commit ourselves to—at the very least—trying to see the world and inhabiting the world as he does. Of course, this is a morally fraught situation. In his exquisite essay “On Love, and Its Reasons,” the philosopher Harry Frankfurt reflects that “lovers are characteristically vulnerable to profound distress” because we exist in a moral universe of competing, sometimes incommensurate obligations. Lovers are continually faced with the possibility of “being caused to love what it would be undesirable for them to love.” Often before we know it, we are placed under obligations to the beloved that we may not have chosen, nor would have chosen were the terms made clear. Only divine love, Frankfurt tantalizes his reader, may be free of such danger.

In any case, friendship demands more of us than we would likely be willing to commit if we knew the true cost behind the sticker price. It is probably to our benefit, in many cases, that we are blissfully unaware of this cost in the fragile early days of a friendship. Perhaps we would have far fewer friends if we were more prescient.

Or perhaps friendship is only truly valued in retrospect. Like my commitment to fatherhood, there is no way to comprehend the depth of one’s affection—and the willingness to sacrifice for it—until it has already taken root. Thinking of the hobbies and interests, as well as the political attitudes and theological beliefs, that I have acquired through friendship, I am grateful now for how I have been changed by my acquaintances-turned-friends. But gratitude is oriented to the past, and my earlier self could not have felt the same way about these acquired attitudes. In fact, my earlier self may have been dismayed at what I have become.

Friendship demands more of us than we would likely be willing to commit if we knew the true cost behind the sticker price.

So, is friendship worth the venture?

It is not a rhetorical question. If we take earlier thinkers at their word, genuine friendship makes a claim on our most fundamental selves, adjoining our flourishing to another soul. It is, more often than we usually admit, a relationship permeable to human frailty and the competing—often alienating—obligations of modern life. Its complexities resist reduction to the contractual (as in commercial ventures), the natural (as in familial bonds), or the biological (as in erotic relationships). So, what vocabulary remains to explain a truly intimate friendship?

It seems to me that we need strong language to account for friendship’s fragile yet sacred value. Friendship is the sort of love that, on the very terms of its vulnerability, invites us to sacrifice our future selves for the sake of something far better than personal autonomy—or even a static sense of self. The ancients and medievals tell us it is impossible for human beings to enjoy the good life without friendship. And we might add, there is no good life worth having that is free from friendship’s costly sacrifices. Such risks require protection, intentionality, and—I suspect—forms of public accountability that may at first appear oddly foreign to us.

If we want to recover a richer, more durable conception of friendship, we have to take its vicissitudes seriously. We need to become practiced at distinguishing genuine friendship from its semblances. And perhaps the very sort of moral and theological therapy required for the present moment lies in the forgotten language of covenant. Modern ills sometimes require premodern remedies.