T

You shall not reap your field right up to its edge.

—Leviticus 19:9

Francis used to tell the brothers not to cultivate all the ground, but to leave a piece of the ground that would produce wild plants. Thus, in their season, they would produce “Brother Flowers” out of love of Him who is called “the flower of the field” and “lily of the valley.”

—Francis of Assisi: Early Documents

The chemically fortified green buzz cuts that most North Americans inflict on our patches of purchased earth remain en vogue; but with apologies to my long-suffering neighbours, I’m thinking about giving my lawn mower (reader, it is me) a break. The results could be magnificent. At least that is what my area park district came to realize. “Unusual and rarely-seen plants are popping up from seeds that have been sleeping here in the soil for over a hundred years,” claims a proud sign by a nearby path. “No longer mowing the turf around the bases of trees allows some long-slumbering native plants to emerge, grow and flourish once again. The reappearance of the historic plants is surprising even to local botanists.” In short, up came red trillium, wood anemone, trout lily, Virginia bluebells, and Solomon’s seal—all because people did nothing at all.

It might be likewise surprising for some to learn that an evangelical college in the same area is awash in ancient Christian practices. Icons deck the walls and incense fills the air. Vigils, Marian devotion, allegorical interpretation of Scripture, and sung Evensong services complement gifted preachers on the jumbotron. Candles compete with fluorescent lights, and the promise of pilgrimage lures some from the prospect of spring break on the beach. This is not the only way of being a Christian at Wheaton College (where I teach), but it certainly is a popular one, toward which many students gravitate especially as they near graduation. And as with our park district, the breakthrough came when we just stopped mowing.

Is there a clearer example of aggressive mowing than the now-dated Bible-reading method called historical criticism (which I’ve criticized in these pages before)? The great translator Robert Alter called this method “excavative,” for only the earliest forms of texts were of any real concern. The aim was to mow through medieval allegory, dogma, liturgy, and legend to aim at (in the words of Charles Augustus Briggs) “the rockbed of the Divine word, in order to recover the real Bible.” But we’ve since come to understand that this method “has never been exempt from the prejudices of its practitioners.”

Accordingly, a new generation of Christians gave their mowers a rest, and stopped assuming that only the ancient Near Eastern or Greco-Roman layers of the past were worthy of investigation. Once we remembered that the Holy Spirit has long been with the church, leading her into all truth, the forgotten flowers began to appear. While teaching at Wheaton College, Professor Robert Webber (1933–2007) faithfully recorded the first of them in his string of remarkable books, but I can testify that in the decades since Webber’s departure, these ancient-future flowers continue to germinate. Without space to name all of them, I can think of at least four recent blossoms, alliterated to bolster my evangelical credibility: meaning, maps, monasticism, and mysticism.

Meaning

It is a beautiful if initially confusing fact that in the ancient Christian world the shorthand for the creed was to call it the “symbol” (symbolon). This connection of symbolism to the birth, passion, and resurrection of Christ is a reminder that the medieval tendency to see meaning in everything is not a poetic pastime, still less a fanciful projection of psychological concerns onto reality. Instead it is an outgrowth of discerning the uncreated Christ to be the centre and circumference of reality. For the medievals, Jesus is the Rosetta stone of cosmic meaning, with whom all things are aglow in the polyphonic resonance of truth, and without whom the world hurdles into centrifugal disconnection. In his book God, Cosmos, and Humankind: The World of Early Christian Symbolism, Gerhart Ladner puts it this way:

So it was that for the medievals the splash of red on the head of a goldfinch signalled the passion, and the sheath and kernel of a nut evoked the human and divine natures of Christ. So it was that Hildegard of Bingen (so perfectly dramatized in the German film Vision) concocted a theology of rocks, gems, and crystals so elaborate as to make even the most ardent modern New Ager blush. Even the cement used to construct cathedrals had meaning in the Middle Ages. (The lime signifies love; the sand, temporal works of mercy.) Such meaning was never monophonic, and could suddenly shift to one register or another; but at the centre of the hive of symbols was always the queen bee herself—the Virgin Mary (who also signified the church) and her son, the risen Christ.

For the medievals, Jesus is the Rosetta stone of cosmic meaning, with whom all things are aglow in the polyphonic resonance of truth, and without whom the world hurdles into centrifugal disconnection.

Modern longing for this kind of meaning is precisely what accounts for the popularity of Jonathan Pageau’s work at The Symbolic World, and such interest comes not a moment too soon. In his excellent book An Introduction to Christian Mysticism, Jason Baxter strings together an impressive list of recent thinkers united in their diagnosis of modern travails, and the common denominator is meaninglessness. “The truths which were formerly within reach of all have become more and more hidden and inaccessible; those who possess them grow fewer and fewer,” laments René Guénon. Flannery O’Connor proposes that “right now the whole world seems to be going through a dark night of the soul.” In The Waste Land, T.S. Eliot describes our condition as a “heap of broken images.” John Burroughs dubs it the “cosmic chill,” and Karl Rahner prefers “spiritual winter.” If these were the complaints of the mown world of last century, how much more can such complaints be intensified today? As Addison Hodges Hart puts it in his insightful Substack, The Pragmatic Mystic, the opposite of symbolism is, unfortunately, diabolism—the effects of which are hand-delivered to us by algorithms every day. The medieval epoch, however, offers a storehouse of subterranean seedlings of meaning—now embedded in Protestants thanks to C.S. Lewis the medievalist—just waiting for the mowers to cease.

Maps

Perhaps the easiest way to contrast the symbolism of the Middle Ages with the deficit of the present is to unfurl one of our proudest tools, Google Earth, or its more practically applied manifestation as Google Maps. Many today casually dismiss the small-minded medievals, who (we falsely assume) thought the world was flat. On the contrary, it is our world that has been flattened, lacking the full-orbed splendour of medieval significance and depth. For plentiful as the information stored in Google Earth may be, there is no clickable layer of “meaning” (even in the pro version).

For contrast, take the Hereford Mappa Mundi from about 1300, one of the Middle Ages’ most spectacular blooms (explore it here). Simply put, this single sheet of painted calfskin is superior technology. Google Earth may be able to take you anywhere, but the technology that generated it can just as easily be used (and no doubt is used) to help bomb different regions of the earth. In fact, the quest for such capacity is how GPS technology came into existence in the first place. But the Mappa Mundi is presided over by a suffering Savior (zoom in here), who will judge the earth for such failures, and whose outstretched arms inflict mercy on such failures as well. Below him is the Virgin Mary, who displays the very breasts he once depended on for food. It is all very well to take aim at the theological dangers of such Marian depictions, so long as we allow such depictions to take aim at our own age’s exploitation of breasts through internet pornography first.

All this is true enough, one might reply. But is the Mappa Mundi “accurate”? Does it not depict griffins and unicorns? While we may have learned more hard facts about biology since the Mappa Mundi was created, at least the map’s creators retained a sense of wonder and reverence about the animals they saw fit to include, however fanciful. The moral wisdom radiating from a leopard or a peacock in medieval bestiaries is far more sophisticated, and playful, than our celebrity-hosted nature shows today, however impressive the camera techniques. We may have expensive lenses to amplify our literal reading of nature, but they had allegorical, moral, and anagogical lenses as well.

When the moral dimension is considered, the Mappa Mundi is very “accurate” indeed—and, I repeat, superior. Many in the present have tried to “decolonize” their maps by de-centring North America and Europe. Good for them. But these reconstructions are far less daring than the Mappa Mundi, which puts what is now India, Iraq, and Iran on top, with England (where the map itself was made!) tucked off in a corner. The Enlightenment gave us Eurocentrism, not the Middle Ages.

But if Eurocentrism is to be lamented, how about self-centrism? Indeed, Google Earth’s only centre is the scroller’s will. But the centre of the world, the navel, for the Mappa Mundi is the Holy Land itself, the only land that has the privilege of being the centre thanks to God’s election of the chosen people (not by merit but by grace). Moreover, it is only Jerusalem that has any right to be the centre of Christendom, as the diverse Christian communities—Armenian, Orthodox, Coptic, Syrians, Ethiopian, Franciscan—radiating in every direction from the Holy Sepulchre attest. (And lest Protestants be left out, it was a California Episcopalian who designed the star in the Sepulchre’s dome!) A simpler way of putting it is that only Jerusalem-centred maps like the Mappa Mundi are up to date, for only they can make sense of new research regarding global Christian communities on offer in books like Vince Bantu’s extraordinary A Multitude of Peoples: Engaging Ancient Christianity’s Global Identity.

Monasticism

It might seem odd to suggest that monasticism is a seed from the Christian past that is germinating again, but the career of one prolific scholar suggests otherwise. Biola professor Greg Peters has unfurled the surprising extent of monasticism’s impact on the present. His deeply researched books include The Story of Monasticism: Retrieving an Ancient Tradition of Contemporary Spirituality and The Monkhood of All Believers. And lest readers come to doubt Peters’s unexpected claim that there have been monastic traditions in all main branches of the Christian tradition, he added another book as well: Reforming the Monastery: Protestant Theologies of the Religious Life. In it, Peters brilliantly parallels Bonhoeffer’s Life Together with the Rule of Benedict, showing Lutheran and Benedictine communities to be nearly identical in spirit and form.

Peters manages this claim by uncovering the original meaning of the word monachos (from where we get “monk”). He traces the first use of the term to mean not “solitaries or even solitary celibates,” but rather “to live according to a unified way of life.” In other words, Jesus’s words “If thine eye be single, thy whole body shall be full of light” (Matthew 6:22) apply to everyone, for to “be a monk was to be spiritually formed so as to live single-mindedly focused on God, living into the fullness of one’s baptismal vows as priests of God’s kingdom.”

Peters proves that the deepest roots of monasticism, if the writings of authorities such as Augustine and John Cassian are to be trusted, are in the unified communities of married and non-married persons on display in Acts 2 and 4. Lest that seem like a Protestant’s special pleading, Peters summons trustworthy Orthodox (Paul Evdokimov) and Catholic (Raimon Panikkar) voices who also called for the monasticism of all. In sum, Peters may offer the only full-scale celebration of monasticism that simultaneously takes Luther’s full-scale critique of monasticism into account. But Peters, a Benedictine oblate himself, manages to do all of this without denigrating the continued need for monasteries in their traditional form. In fact, Peters makes traditional monasticism so appealing that, just as parents once hid their children from Bernard of Clairvaux lest his compelling rhetoric draw them to the monastery, I advise parents with current Wheaton students hoping for grandchildren to urge me not to assign any of Peters’s captivating books!

Mysticism

Still, perhaps the most important ancient seed of the Middle Ages now sprouting again is the meditation and mysticism that marked that epoch as it has few others. If, as Jamie Kreiner recently argued, medieval monks had special techniques for battling distraction, we need such wisdom as never before. Of course, it would be easy here to point to how Catholic and Orthodox Christians have cultivated the focused sense of mystical union with God that was so prevalent in the Middle Ages. One need look no further than to the finally completed English translation of the Philokalia among the Orthodox, or to Catholics such as Thomas Merton, Thomas Keating, and the trilogy (Into the Silent Land, A Sunlit Absence, and An Ocean of Light) by Villanova’s remarkable Augustinian priest Martin Laird. This is all to be gratefully expected.

But Protestant traditions (as I have pointed out here before) have especially nurtured the ancient seedling of mysticism as well. Laird’s trilogy is in fact dedicated to a contemporary Anglican anchorite (yes, they still exist), Martha Reeves, who under the pen name Maggie Ross has penned her own vertiginously learned two-volume treatise on silence. Ross is in the tradition of the great Anglican mystic Evelyn Underhill (1875–1941), whose modern revival of medieval mysticism was refined and completed the very year Thomas Merton was born. (“Whoever is that little woman?” the great Orthodox theologian Sergius Bulgakov once said of Underhill at a conference. “She knows far too much.”) And long before both Ross and Underhill was the notable Anglican William Law (1686–1761), who took the Protestant doctrine of grace to its natural conclusion, urging us to relax our own mental efforts as the anonymous medieval author of The Cloud of Unknowing also advised, and to reside in silence before the God who, on Calvary, has accomplished it all.

But lest such Anglican appeals to mysticism seem disconnected from the on-the-ground realities of evangelicalism, other new books indicate that evangelicals are not flirting with contemplation so much as—drawing on Calvin, Baxter, Edwards, and Wesley—embracing contemplation. For as Kenneth Stewart argues in his book In Search of Ancient Roots: The Christian Past and the Evangelical Identity Crisis, adherence to ancient and medieval Christianity is not a new Protestant phenomenon, but the recovery of an impulse without which there would be no Protestantism at all.

But What About . . . ?

Admittedly, the Middle Ages did not generate flowers alone; and to call attention to its lilacs and lilies is not to overlook its noxious thistles such as the pogroms or the Crusades. (My writing a book in critique of the latter I hope exonerates me from irresponsible idealization.) Notice that in my string of alliterations I am not calling for the recovery of medieval militarism, let alone its medicinal techniques (even if some of them did work). James K.A. Smith is right to remind us of Annie Dillard’s wisdom: “The absolute is available to everyone in every age. There was never a time more holy than ours, and never a less.”

It is then that our clear perception of their deficit regarding pluralism and penicillin matures into the realization of our deficit in solitude and semeiotics.

But it is precisely because that is true that we look to those from the past with different, frequently more lucid, modes of access to the absolute. It is then that our clear perception of their deficit regarding pluralism and penicillin matures into the realization of our deficit in solitude and semeiotics. Such an exchange is possible not primarily because of the tools of historical investigation. It is possible first and foremost because “he is not the God of the dead, but the God of the living” (Mark 12:27). Gertrude of Helfta (read her!), Herrad of Landsburg (read her as well!), and Hugh of St. Victor (don’t miss this site) are not dead; they are our contemporaries, because the communion of saints is outside time.

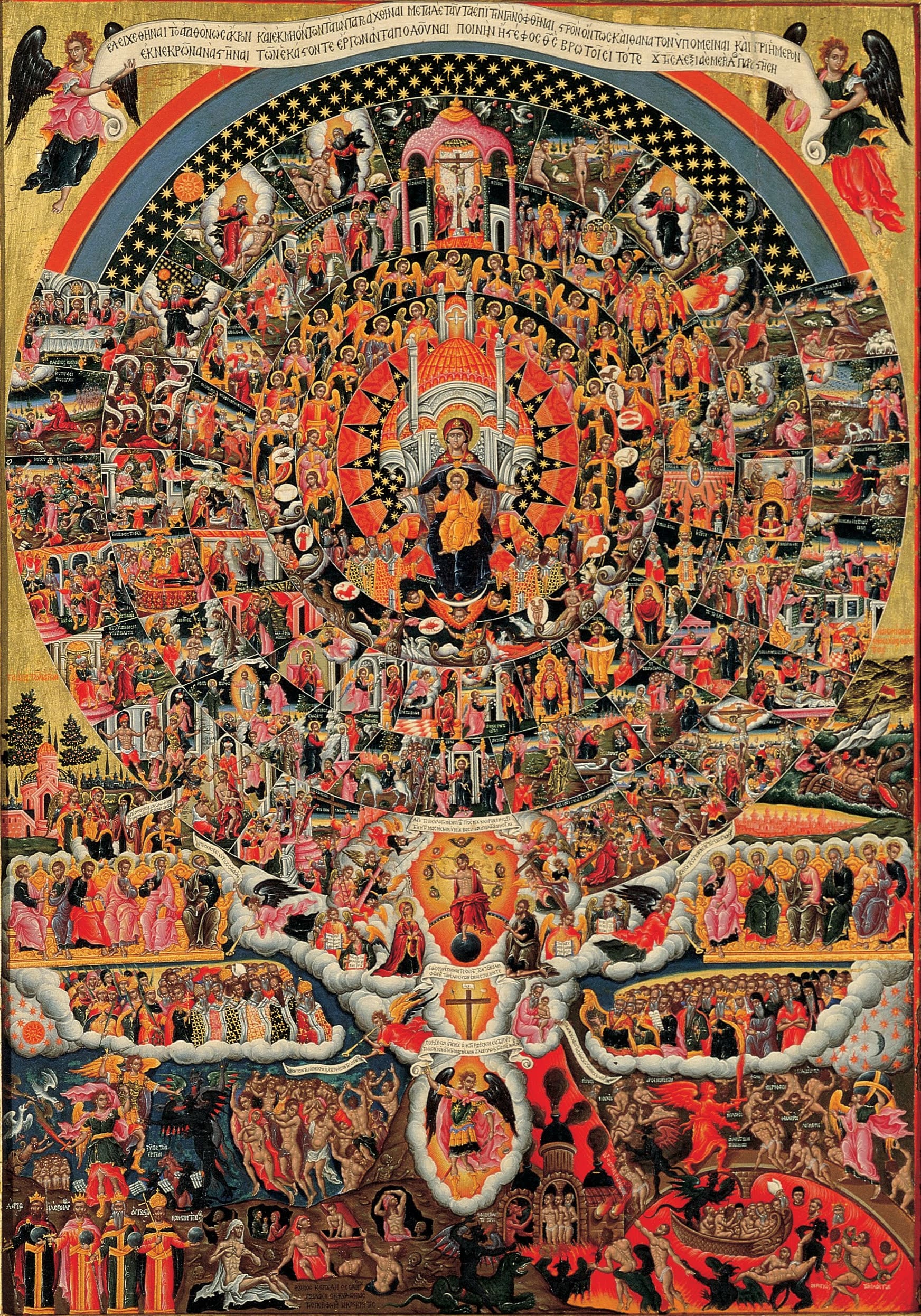

And that undivided heavenly communion, as any glance at a Byzantine-inspired icon or perusal of the concluding cantos of Dante’s Paradiso will tell you, is the most beautiful flower of all.

Special thanks to my colleague Chris Vlachos for word about the Protestant contribution to the Holy Sepulchre dome, to my student Susanna Spacek for the references to Leviticus and St. Francis from Seeing Differently, and to my student Samuel Whatley for the article about Hildegard of Bingen’s medical prowess.