C

Community as an ideal gets thrown around a lot these days, but fewer and fewer are experiencing it. It tends to get conflated with “sense of community,” which can emanate from friendships and certain kinds of social networks, the experience of working with a dedicated group of volunteers or in a close-knit organization, serving a social movement or being part of a dynamic chain of individual relationships. All these provide psychic and civic benefits, but they fall short of a true community’s demands and rewards.

An actual community is much harder to create and, especially in the modern West, still harder to sustain. It requires commitment to a certain social order—and, crucially, a place—that by definition must constrain individual choice. In return for security, support, and belonging, members surrender some of their freedom.

In a North American context increasingly allergic to constraints imposed from beyond the self, there are fewer and fewer examples of the rich kinds of community we crave—few want to compromise their privacy and surrender their freedom. Aside from the military, interestingly, most of the reigning examples of covenantal commitment tend to be religious. In my own Orthodox Jewish community, the great practical, moral, and personal support each member treasures comes at a price woven into the very fabric of our interdependence. Each one of us is expected to adhere to a particular lifestyle and uphold certain responsibilities. We must live within walking distance of our place of worship, keep the Sabbath and frequent holidays, and send our children to one of the community’s schools. We must also be available to help others—mentoring youth, donating money, volunteering for work. To earn acceptance and respect, we must model good behaviour at all times.

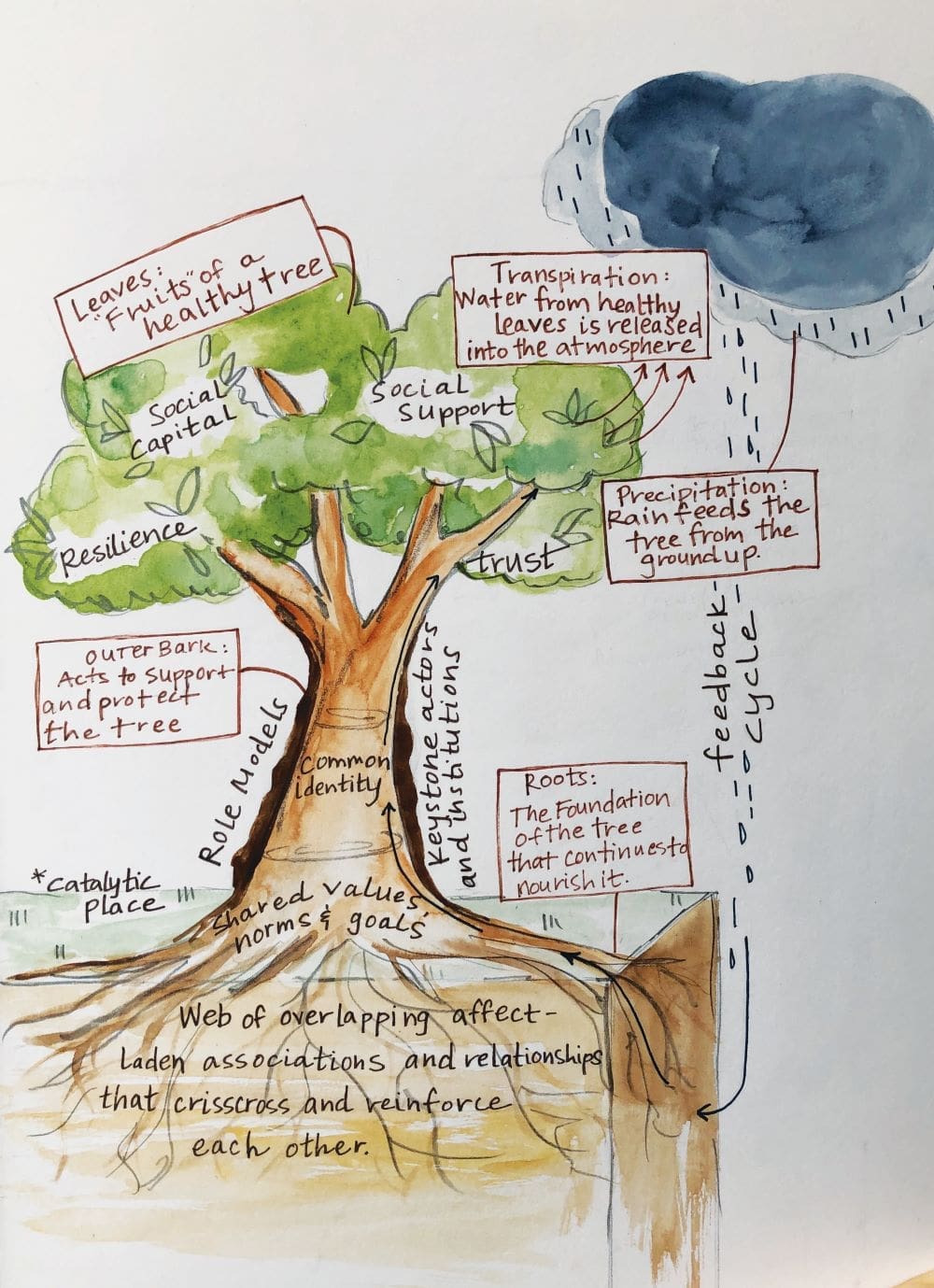

Community formation cannot be easily explained or laid out in a plan of action. At times, it is more mystery than mechanics, subject to a wide range of factors that are beyond the control of any one actor. In general, groups begin as a product of strong, overlapping, interpersonal relationships, which produces a series of formal and informal associations and institutions that bring people together around common goals and values. Keystone actors and institutions emerge as central supporting hubs, working to break down barriers and integrate disparate parts; influence people to increase their commitment to and aspirations for the group; and foster relationships and partnerships that together create a systemic effect well beyond the individuals directly involved. All these activities build trust where it may not have existed.

As group ties strengthen, a common identity and narrative emerge, with greater effort invested in strengthening the social mechanisms that weave people together. The more productively these mechanisms reinforce a common outlook, cooperation, and vision for advancing the common good, the more robust a community becomes and the better it is able to address its various challenges. The resulting web of ties grows in resilience and dynamism as the group grows in cohesion. Divisions and exclusion are better tackled as a stronger sense of common destiny forms. Social capital is enhanced as mechanisms to counter deviance and encourage cooperation emerge. Authority figures gain credibility as agreement on what people have in common is reached.

The role of informal, everyday interaction—sometimes unpredictable and serendipitous—should not be underestimated. But this requires a place-based social infrastructure that encourages such interaction. Neighbourhood churches (or other places of worship), religious activities, schools, butcher shops, markets, town squares, beauty parlours, taverns, pubs, general stores, and libraries used to provide this infrastructure, but new media, cars, changes in shopping patterns, a greater emphasis on privacy, and more intensive work schedules—along with longer-term trends like rising income levels, the entry of women into the workforce, shrinking family size, and the decline of religion—have had weakening effects.

Or, to introduce a metaphor, the roots (social ties) must become a sapling and then a tree with a trunk built on shared values and identity and bolstered by institutions and leaders. The tree must have diverse branches as it grows, offering a healthy mixture of different goals, each with their own niche but mutually supportive of each other. The fruits of the tree must support the environment so that it, in turn, can feed the roots, multiplying social ties and nurturing an ever more fertile ecosystem.

Illustration by Lisa Shirk