I

In 2006 John Mayer had a hit song called “Waiting on the World to Change.” Much has changed since 2006, but not this approach to making the world a better place. Most people want to change some things about society, but few of us feel we are in a position to do much. And so we wait. We see ourselves as small and living in the shadows of the grand dramas of our age, like bystanders watching superheroes in a Marvel story. We neglect the power and responsibility we actually have.

When we believe that we are not very responsible for change if we are not very powerful, we can find ourselves participants in tragic scenarios. A recent heartbreaking article in The State about executions in South Carolina featured interviews and stories from men who had served as executioners. Many of them found the work distasteful and distressing. The author describes one of the men this way: “He would be consumed by stress for weeks before each execution, and afterwards, it would be at least five days until he felt somewhat back to normal.” Others reported similar experiences, and many of the executioners now oppose the death penalty. But the men also felt unable to quit, because serving in the role made one more eligible for leadership positions and promotions. As conflicted as these men felt about taking life, many could not imagine taking a pay cut or changing jobs to avoid doing it. They hoped the law would be overturned, but they could not imagine losing status to slow the speed of executions in their state.

Many of us are waiting for Thor to drop in with his hammer. We want change, but we are not willing to consider our responsibility to help bring it about. We are hoping that someone who has money and status to spare will use some of it to make the world better. Or we are waiting until we have enough power to make our move. Once the radioactive spider bites us, we will do something. But it may very well be that the world is transformed one widow’s mite at a time. It is not the spare but the sacrificial that is needed.

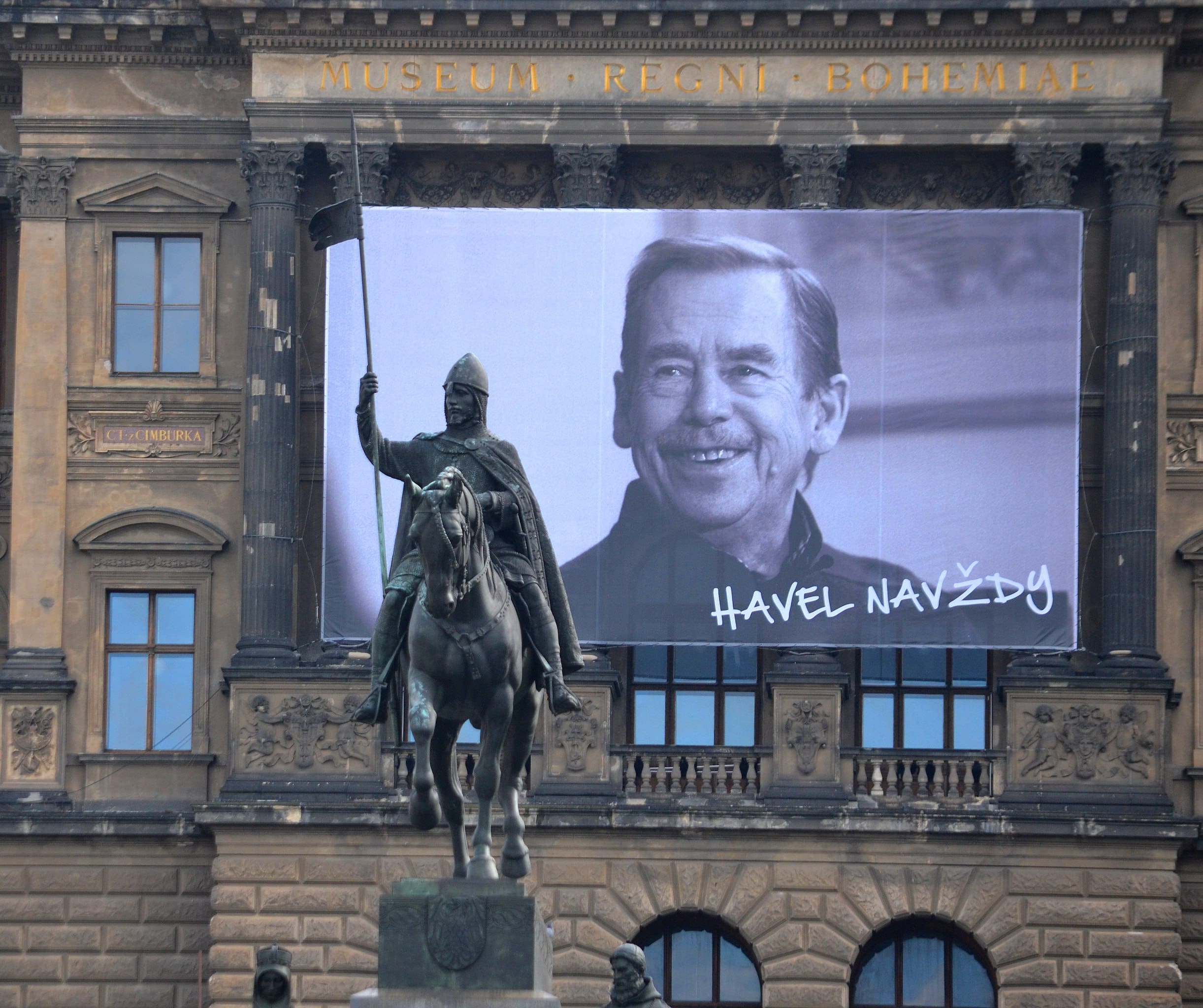

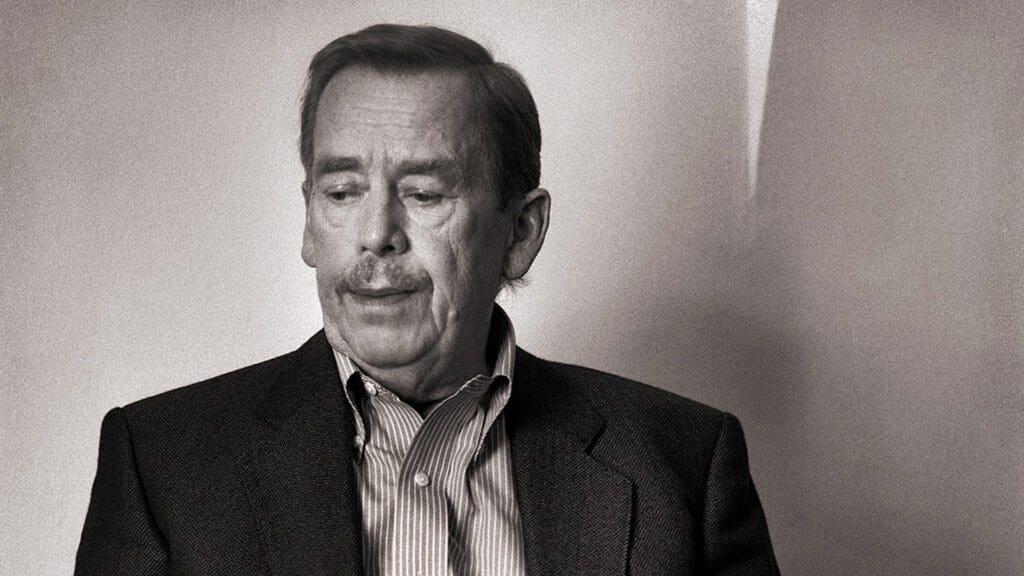

Those who think our culture can be changed only by those with obvious power should consider an alternative philosophical perspective. In 1978 Václav Havel published an essay titled “The Power of the Powerless.” Havel was writing from behind the iron curtain in Czechoslovakia, in a society he described as “post-totalitarian.” For Havel, the Soviet system was beyond a traditional dictatorship; its roots were so deep that it no longer relied on a single leader. It had its own institutional momentum, running on ideology, a system of beliefs that replaced reality. That ideology was imbibed from top to bottom in the power structure.

For Havel, the Soviet system was much bigger than the imposition of rules from a handful of powerful figures. It had come to rely on its own subjects for perpetuation. Using the example of a greengrocer who unthinkingly puts a “Workers of the World Unite” sign in the shop window simply because life is easier that way, Havel explained that the people in Czechoslovakia were engaging in “auto-totality.” By playing along, they kept the system going. The people were not simply the victims of the Soviet system; they were simultaneously its perpetrators.

Living in the truth might never translate into a political program; it would be contingent and diverse and, primarily, human. It was about pursuing a better life.

“Power of the Powerless” was written to the West, to inform them about the “dissidents” they were looking for in the East. Then as now, Westerners thought that resistance to an oppressive government would take the form of political-opposition parties, capitalist movements, protests, and perhaps military resistance. Instead of any of those things, Havel suggested that a dissident was anyone “living in the truth”—who refused to accept ideology over reality and who pursued the aims of life rather than the aims of the system. It could be as simple as listening to rock music that the state opposed. Living in the truth might never translate into a political program; it would be contingent and diverse and, primarily, human. It was about pursuing a better life. That better life might lead to a changed political system, but it wouldn’t come about through political change.

How would a better life for all come about, if not through political change or direct resistance to Moscow? Havel did not recommend taking to the streets to face off against Soviet soldiers; he advocated an “existential revolution.” He wanted a moral transformation of society, a “rehabilitation of values like trust, openness, responsibility, solidarity, love.” People should simply make a better life right where they were. They should do a good job at work, be good to their neighbours, choose reality over ideology, and take responsibility for their own actions and environment. For the greengrocer, he could begin by not putting up the sign if he did not believe in it, and then facing the consequences. Havel knew from his own friends and experiences that the denial of ideology could lead to negative personal and occupational outcomes.

Havel’s perspective was and is baffling for many. It offers no obvious dissident heroes and relies on no special abilities or aptitudes. It depends on everyday people making good choices every day. It suggests that people who can be imprisoned for reading banned literature can begin to make a better life for themselves and others without the benefit of increased liberty. It seems like a fantastical form of resistance to a tyrannical system. And it is remarkable for how much responsibility it places on the people within the system, rather than blaming the people at the top of the hierarchy.

What Havel realized is that we are not simply passive victims of our society; we are participants in it, even when we are victims. He quoted his friend Jan Patočka, who “used to say that the most interesting thing about responsibility is that we carry it with us everywhere.” Some people in the United States today believe we cannot achieve change without controlling Congress or the Supreme Court or changing legislation. We think we need all the infinity stones. Havel’s perspective reminds us that we all make choices in our lives that make us more or less honest, our environment more hospitable or more hostile, and life better or worse for all. If we are unwilling executioners, we can wait for executions to cease through legislation, or we can all choose, one by one, not to execute anyone. We may face consequences for choices like that, but we will also be changing the world around us.

If Havel’s approach seems far-fetched, we can see it at work in the past in the efforts of the Freedom Riders, who rode through the American South in 1961 in order to integrate buses and move civil rights efforts forward. First organized by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), the rides were mainly led by college students who had relatively little standing in society and everything to lose. These were not people with money or power to spare. And they risked what they did have in their efforts. The first trips required many students to drop out of college. Bernard Lafayette Jr. was a student at American Baptist Theological Seminary. In a PBS documentary about the Freedom Riders he shares, “It was not an easy decision, because what it meant was dropping out of school in the midst of our final exams. And for some of us, we were the first generation to go to college. Our parents had really made sacrifices and we were making a decision to drop out.”

People like Lafayette decided to live in the truth. Black people should have the same rights as white people. He would live as though they did. He would ride the bus and face the consequences. And the consequences were real. Violence brought an abrupt end to the first two bus trips. It was apparent that riders would be attacked and maybe even killed. That did not halt the movement. Another student, Jim Zwerg, wrote a letter to his parents on May 16, 1961, telling them that “we were all again made aware of what we can expect to face: jail, extreme violence, or death.” He went anyway.

The students were relentless. Their living in the truth revealed the lie—despite legislation, the South was not integrated. The government did not have a handle on the situation. The South was not a peaceable place. It didn’t matter that these students were, for the most part, previously unknown. When the Kennedy brothers asked John Siegenthaler to get in touch with Diane Nash to slow or stop the students, he said, “Who the hell is Diane Nash?” These students were not initially prominent, but that did not stop their words and actions from being powerful. When Seigenthaler did speak to Nash on the phone, asking her to stop the rides on behalf of the federal government, she told him, “Sir, you should know. We all signed our last wills and testaments last night. We know someone will be killed, but we cannot let violence overcome non-violence.”

Eventually there were over 430 Freedom Riders, and over 300 of them were imprisoned in Parchman Prison. They came from all over the country, at all kinds of personal costs. Many people were severely beaten. Many missed graduation and opportunities. Many acquired a criminal record. Some were disowned by their families. But they kept coming. And soon they came without being organized or obviously led. Individuals took themselves to the bus depots and got on board the movement. According to Pauline Knight-Ofosu, “it was like a wave or a wind that you didn’t know where it was coming from or where it was going, but you knew that you were supposed to be there. Nobody asked me. Nobody told me. It was like putting yeast in bread. It was a leavening effect.” These people did not wait until they had seized power to do something. They took it upon themselves to change their world.

The efforts of the Freedom Riders got the public’s attention. Their living in the truth reminded others to do the same. In a live version of “We Shall Overcome,” Pete Seeger emphasized the last verse as a lesson learned from the Freedom Riders: “The most important verse is the one they wrote down in Montgomery, Alabama. They said ‘we are not afraid.’ And the young people taught everybody else a lesson, all the older people that had learned how to compromise and be polite and get along and leave things as they were. The young people taught us all a lesson.” They woke others up from their auto-totality. They reminded them not to live the lie that everything was okay.

We may honour the civil rights movement now, but we do not often emulate it. The Freedom Riders had bigger priorities than personal gain, and they were willing to pay a personal price for those priorities. John Lewis was then a senior at American Baptist Theological Seminary. He said then that “at this time human dignity is the most important thing in my life, that justice and freedom might come to the deep South.” He was pursuing justice and freedom through whatever means were available. He was not counting the cost.

In a speech in Birmingham in 1962, Martin Luther King Jr. told the audience that people were being arrested “for the cause of freedom and human dignity,” but that the charge was to “keep this movement moving. . . . As long as we keep moving like we are moving, the power structure of Birmingham will have to give in.” They were outside the power structure, but they were not waiting on power to change that structure. What would it look like? What would it cost? King told the crowd, “And don’t worry about your children, they are going to be alright. Don’t hold them back if they want to go to jail. For they are doing a job for not only themselves, but for all of America and for all mankind.”

It takes a considerable amount of courage to take that kind of responsibility for the world. As Russell Moore says in his recent book The Courage to Stand, “The courage to stand is the courage to be crucified.” This is the “costly grace” that Dietrich Bonhoeffer encouraged us to accept rather than “cheap grace.” It is the grace that includes Jesus’s invitation to pick up our cross and follow him.

Most of us would rather not go to jail. And we would rather have our children graduate. We would rather wait for the Avengers to show up. Yet the courage to stand, the courage to be crucified, may well be the kind of courage required to change the world. There may be times when the pursuit of success or even yielding to our survival instinct is a moral compromise. In a recent essay in Mere Orthodoxy, Jake Meador describes the options available to American Christians in our political climate and suggests that not only should we resist the allure of unjust power but we should be ready “to become martyrs of a sort” when needed.

The courage to live in the truth, whatever the cost, will not always yield immediate or easy results. But it will make it easier for us to live with ourselves and others, because we will have self-respect. In her essay “On Self-Respect,” Joan Didion writes that “character—the willingness to accept responsibility for one’s own life—is the source from which self-respect springs.” She describes self-respect as a discipline and a habit of mind that has to be nurtured and sustained. But “it is a question of recognizing that anything worth having has its price. People who respect themselves are willing to accept the risk. . . . They are willing to invest something of themselves; they may not play at all, but when they do play, they know the odds.”

People with self-respect recognize that they must be willing to pay for what they want, however costly it is. And that is not about home prices or student loans as much as it is about social change and a more human existence. If we want better government or policing or education, we need to be willing to engage all those realms, not just through policy or politicians, but as real people willing to sacrifice something to bring about change. We cannot wait for our friendly neighbourhood Spiderman.

Marvel stories may fuel our desire for heroism and justice, but we should not take from them a reverence for power that distorts reality. We don’t require a better social or financial position or special abilities in order to help others. We don’t need the Avengers. That is living in the lie. Believing that significant power is needed to change the world encourages our own auto-totality with conditions we claim not to accept.

We may not have the ability to reshape our world in the way that Wanda Maximoff does, but we are not passive victims of our society; we are participants in it. While we do not all have the same place in the power structure, none of us is outside it. Our responsibilities may vary, but responsibility itself persists everywhere. And responsibility—not power—is the root of change, in ourselves and in society. We need courage, not comic book characters.

When many people take responsibility for things beyond themselves, there is that leavening effect which is the “power of the powerless.” Living in the truth may mean walking a hard road. Lies do not like to be exposed. But as Havel asks at the end of “Power of the Powerless,” “The real question is whether the ‘brighter future’ is really always so distant. What if, on the contrary, it has been here for a long time already, and only our own blindness and weakness has prevented us from seeing it around us and within us, and kept us from developing it?”