E

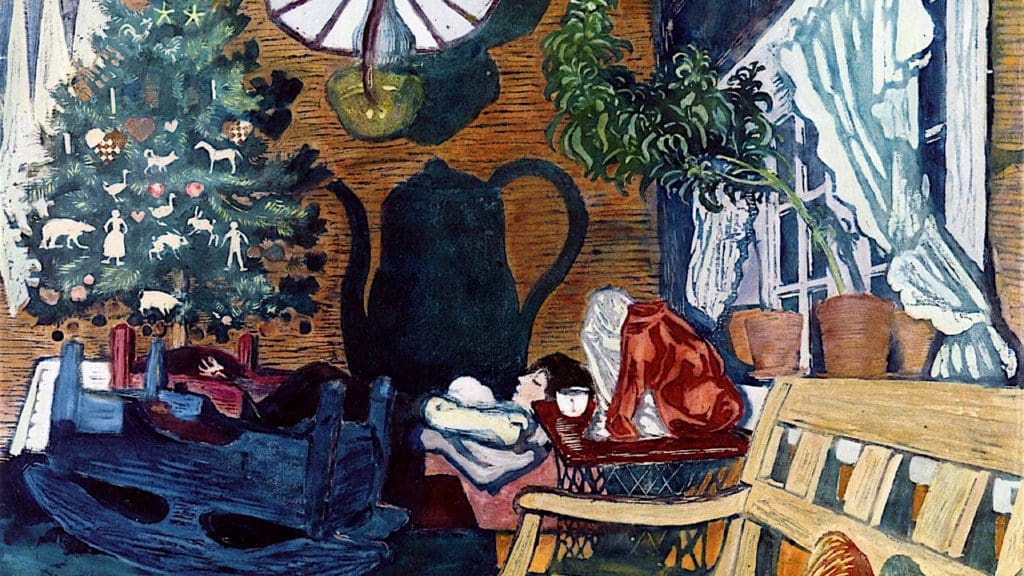

Each year my wife and I wrap twenty-four books, which our children open each night in December, leading up to Christmas. Many of them are classics I read when I was young, like our well-worn copy of Astrid Lindgren’s The Tomten, or Ezra Jack Keats’s The Snowy Day. Some are intriguing books we pick up along the way—this year I added Hisako Aoki’s charming Santa’s Favorite Story, Kenard Pak’s Goodbye Autumn, Hello Winter, and the quirky Olive, the Other Reindeer (who is actually a dog) by Vivian Walsh and J. Otto Seibold. We’ve all come to enjoy the ritual of opening what we call our “Advent books” each night, to be delighted by a familiar favourite or surprised by a new addition.

Last year I introduced a strange and wonderful book I’ve grown to love: William Kurelek’s A Northern Nativity. The book is so fascinating because it’s unique among the others; it’s not a straightforward retelling of a Gospel story, nor a saccharine Santa-centric tale, nor a sentimental tale of childhood nostalgia. To give you a sense of its tone, A Northern Nativity begins with this haunting epigraph:

If it happened here

as it happened there . . .

If it happened now

as it happened then . . .

Who would have seen the miracle?

Who would have brought gifts?

Who would have taken them in?

Kurelek’s book is deeply personal and devotional, and his ruminations about the nativity are imbued with deep sadness—sadness at both his own rejection of faith as a youth (he was an adult convert to Catholicism, in his late thirties) and the world’s seeming ignorance of God. This is an unusual approach to Christmas, to be sure, but it’s what makes A Northern Nativity a singular and affecting book.

William Kurelek is considered one of Canada’s greatest twentieth-century artists, but I hadn’t heard of him (nor have many other people under age forty, it seems) until I discovered his work by chance, when I came across one of his books at a used bookstore in my neighbourhood several years ago. Kurelek is a compelling and complicated figure—an artist with a workmanlike approach (he called his work “craft, rather than art”) yet also a sense of divine calling, a painter known for seemingly cheery, bright depictions of childhood but also dark, disturbed paintings that depicted his own mental illness.

Kurelek’s book is deeply personal and devotional, and his ruminations about the nativity are imbued with deep sadness.

Kurelek felt he had an artistic vocation at an early age. Often at odds with his strict father, who would have preferred his son to choose a more lucrative occupation, Kurelek strove for success to prove that his career could be a respectable one. He was absurdly prolific, often painting all day with little thought for food or rest, and highly acclaimed during his lifetime, being awarded (among other honours) the Order of Canada. His paintings regularly sell for tens to hundreds of thousands of dollars. There was a renaissance of public interest in his work ten years ago, when the biographical documentary film William Kurelek’s The Maze was rereleased and a retrospective exhibit of his paintings toured Canada. (Convivium ran an article about Kurelek’s religious inspiration in 2012.)

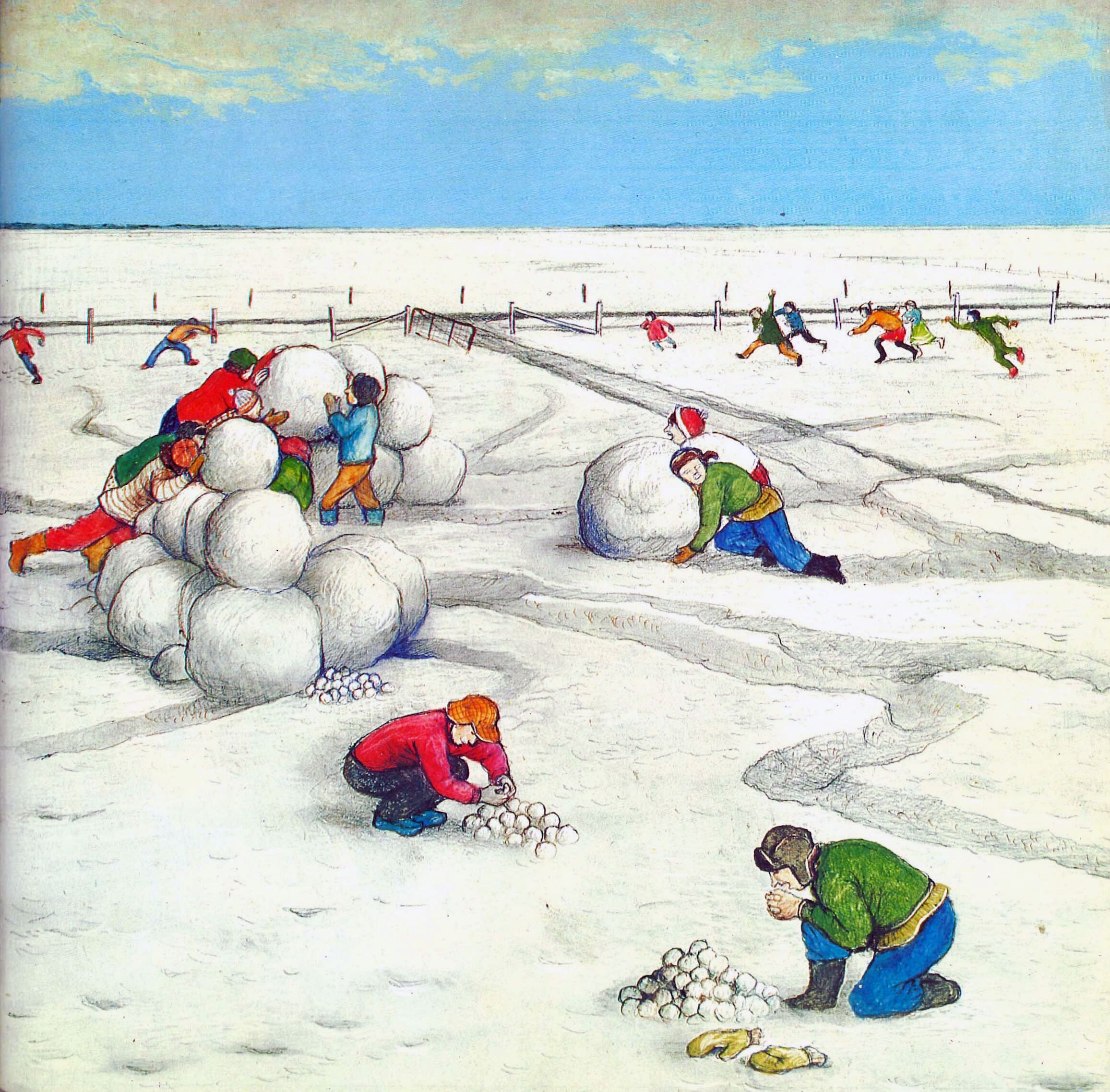

Kurelek’s best-known paintings are probably the pastoral scenes of prairie life he referred to as his “potboilers,” many of which are collected in the books A Prairie Boy’s Summer and A Prairie Boy’s Winter, the latter of which was the first Kurelek book I discovered and shared with my children. It quickly became a favourite when it was added to our Advent repertoire. It wasn’t until I started combing my local library’s catalogue for other books by Kurelek that I came across A Northern Nativity, subtitled Christmas Dreams of a Prairie Boy.

By then I’d learned more about the sad and complex story of the artist’s life. Far from being the “Canadian Norman Rockwell” (not an uncommon epithet for Kurelek), as one might be tempted to think upon reading his first two Prairie Boy books, with their idyllic scenes of schoolyard skating rinks and farmyard hijinks, Kurelek was an artist drawn as much to the darkness of his own soul and his apocalyptic vision of the world as he was to recreating the bucolic landscapes of his youth in Alberta and Manitoba.

“Snowball Weather” from A Prairie Boy’s Winter.

I was strangely captivated by A Northern Nativity by its second page and was in tears by its end. Many things make this book special within Kurelek’s output, but what’s most remarkable is how it illuminates spiritual truths of Christmas with an overarching sense of melancholy—tragedy even—at the world’s ignorance, willful or otherwise, of the gift of the incarnation.

The notion of Christmas as tragic, or the nativity as an event that is accompanied by sadness, feels, at first, utterly foreign. If any time in the Christian calendar should be lachrymose, surely it is Lent, not Christmas. Even Advent, which we tend to understand as a season of joyful anticipation, might be a candidate; as the Episcopal theologian Fleming Routledge reminds us, “Advent begins in the dark.” But against the backdrop of Kurelek’s biography, A Northern Nativity’s melancholy take on Christmas begins to make sense and offers some profound insights about what it means to live as a Christian in what Routledge calls “a world of profound darkness and distress, pervasive sin and evil.”

A Northern Nativity features twenty paintings of the Holy Family in various settings across 1970s Canada, accompanied by personal stories that Kurelek presents as a series of dream-visions he has as a young boy. In each painting and story, Mary, Jesus, and Joseph (the latter occasionally absent) are depicted in mundane Canadian scenes, places like ski resorts, gas stations, and farms. Only a modest, cartoonish series of lines emanating from their heads identifies them as special—simple line-drawing halos that, while nothing like the gold you might see in an Orthodox icon, highlight their holiness. Kurelek is present as a character as well, sometimes depicted in the painting as a marginal figure, peeking at the family from a safe distance, other times only mentioned as an observer looking in at the painted scene.

Against the backdrop of Kurelek’s biography, A Northern Nativity’s melancholy take on Christmas begins to make sense.

Central to the book’s vision is Kurelek’s Catholic conversion in 1957. Born into a Ukrainian immigrant family whose faith was ostensibly Orthodox, Kurelek had, in his view, an essentially non-religious childhood and atheist youth. He was plagued for years by mental and relational brokenness, which led him to seriously seek help, first in psychology and subsequently in faith, which he was introduced to by an occupational therapist. His works painted at the height of his depression—many at a psychiatric hospital in London, where he lived and worked for several years, and where he endured a suicide attempt and multiple sessions of electroshock therapy—are deeply disturbing. (“Even the worst times were in a sense necessary to go through,” he would later say of this time. “All these things were ordained by God.”)

The most famous of these paintings, 1953’s The Maze (it was the cover of Van Halen’s 1981 album Fair Warning), is a depiction of the inside of the artist’s skull, and it is bleak. A rat lies curled in the centre, seemingly dead or paralyzed by its inability to escape the various sections of the titular maze, which depict abuse, bullying, suicide, and other horrors. Titles of other Kurelek paintings in this period make no secret of their misanthropic and hopeless spirit: I Spit on Life, Where Am I? Who Am I? What Am I?, and Behold Man Without God.

Kurelek, who died of cancer at age fifty in 1977, seemed to feel that he had come to faith too late. This is one reason the paintings in A Northern Nativity are tinged with sadness: while many of the scenes are hopeful and moving, there are plentiful reminders that the world at large ignores or rejects what the nativity represents, and that the artist himself, as a character, is likewise unable to accept or comprehend it. (One painting has a quote from St. Augustine’s Confessions carved into a barn wall: “Late have I loved you, O beauty ever ancient, ever new.”)

A Northern Nativity is somewhat uncomfortably shoehorned into the Prairie Boy series. Like the others, it’s autobiographical, but unlike those books, which offer straightforward memoir-esque vignettes about the young William’s childhood (Kurelek writes in the third person), A Northern Nativity depicts a time-shifting, semi-fictional, magically realistic world. The narrative device of the book is that young William is having trouble falling asleep on Christmas Eve, and each of the paintings depicts a dream he has—dreams that “start and end with questions: If it happened there, why not here? If it happened then, why not now?” Though the twelve-year-old William is the narrator through whose eyes we see the visions, the events depicted in the illustrations are best understood in the light of the mature Kurelek’s later life.

This personal perspective is especially clear in the ninth painting, Across the River from the Capital, which shows William’s dream of himself as itinerant adult “Bill,” proud “of owing no one anything,” in a sleeping bag near the Ottawa River. (A brief afterword suggests this is based on Kurelek’s experience.) Mary holds her baby, who reaches out to gently touch the scowling man’s forehead as if to bless him. “Buzz off, will you!” is Bill’s response. The young William cries out in his dream, “That can’t be me. I’ll never reject him!” Kurelek responds with a rhetorical question about his younger self: “Was he really ready to give up his dream of independence?”

“Across the River from the Capital” from A Northern Nativity.

Some of the paintings are less personal and more social, and seemingly meant to disrupt Eurocentric nativity art in which the Holy Family is lily-white. Kurelek paints Mary and Jesus in traditional Inuit clothing, sitting in an igloo as Joseph hitches up a dogsled; as First Nations people looking for shelter at an “Indian trappers’ encampment in Northern Quebec”; and as a black family eating Christmas dinner at a Salvation Army hostel in Halifax. The language he uses isn’t particularly progressive, and the social commentary is sometimes obscure. (William notices there is “something deeper” to the fact that “the Family’s skin is black” in the Halifax scene, but it’s not quite clear what Kurelek intends the reader to understand.) But these nativity paintings can be seen as a part of his long-standing interest in depicting life in Canada’s “ethnic” communities. He produced several series of paintings about, for example, the Jewish, Francophone, and Inuit communities, and we can assume he would have continued to do so had he lived longer.

More than this, these nativity paintings proclaim that Christ comes, as Kurelek writes, “as a light to all nations.” In the Inuit scene, William proclaims, “And Artic nature sings / And Arctic nature sings!” Kurelek treats this as a comic misremembering of the carol, but it’s clear he also wants to use it as a way to reclaim the meaning of Christmas celebration beyond white, urban Canada. In the “ethnic” paintings, the family tends to be recognized and welcomed. They’re also helped or worshipped by working-class people—rural families, fishermen, construction workers, and gas-station attendants—and ignored by comfortable middle-class skiers, “shoppers,” and tourists. An answer to Kurelek’s question “Who would have seen the miracle?” begins to emerge.

“At the Falls” from A Northern Nativity.

The fourteenth painting, At the Falls, showcases another side of Kurelek’s pain, this time at the thought not of his own rejection of Christ but of the world’s. A crowd of tourists are viewing the frozen falls, “dazzling in the winter sun.” Mother and child stand behind the crowd, Mary holding Jesus up to give him a better view. The falls are lavishly depicted and reverently described, but William is pained that no one notices the miracle behind them. He implores them to “turn and look,” but, Kurelek poignantly writes, “William can’t wake the people.” It’s easy to see this as a sort of defeated commentary on the artist’s evangelistic efforts. There’s a sense of resigned melancholy, of William facing the possibility that what he called his “didactic” works, divinely sanctioned though he may have felt them to be, were fruitless.

Kurelek could be uncomfortably direct with the “message” of his art when he wanted to.

Kurelek could be uncomfortably direct with the “message” of his art when he wanted to. He was unflinching about the bleakness of man’s inhumanity to man, the darkness he felt in his own soul, and the necessity of the gospel. Much of his work is now housed at the Niagara Falls Art Gallery, which I had a chance to visit this summer. The current exhibition included a re-creation of his workspace, a cluttered, claustrophobic basement room in his home, the property on which the city of Toronto famously rejected his application to build a bomb shelter. (Kurelek believed nuclear war was imminent in the 1970s, but I feel almost certain he would have happily painted in it had the permits been granted.) The rest of the modest Kurelek wing had a selection of paintings from his illustration of the Gospel of Matthew (he made 160 of them after visiting the Holy Land to take reference photos), the large and striking All Things Betray Thee Who Betrayest Me (which I like to call the “Spooky Cabbage Painting,” as it depicts an alienated and unsettled Kurelek in a mental hospital looking out the window at an eerily moonlit field of vegetation), and several graphic paintings depicting abortion, torture, and nuclear war. These three walls—one religious, one existential, one apocalyptic—offer a pretty accurate summation of his life’s work. That these paintings hang in a basement above which cheery children’s art camps are held might have confirmed Kurelek’s fears that his message was ignored, but that they are displayed at all would perhaps have heartened him.

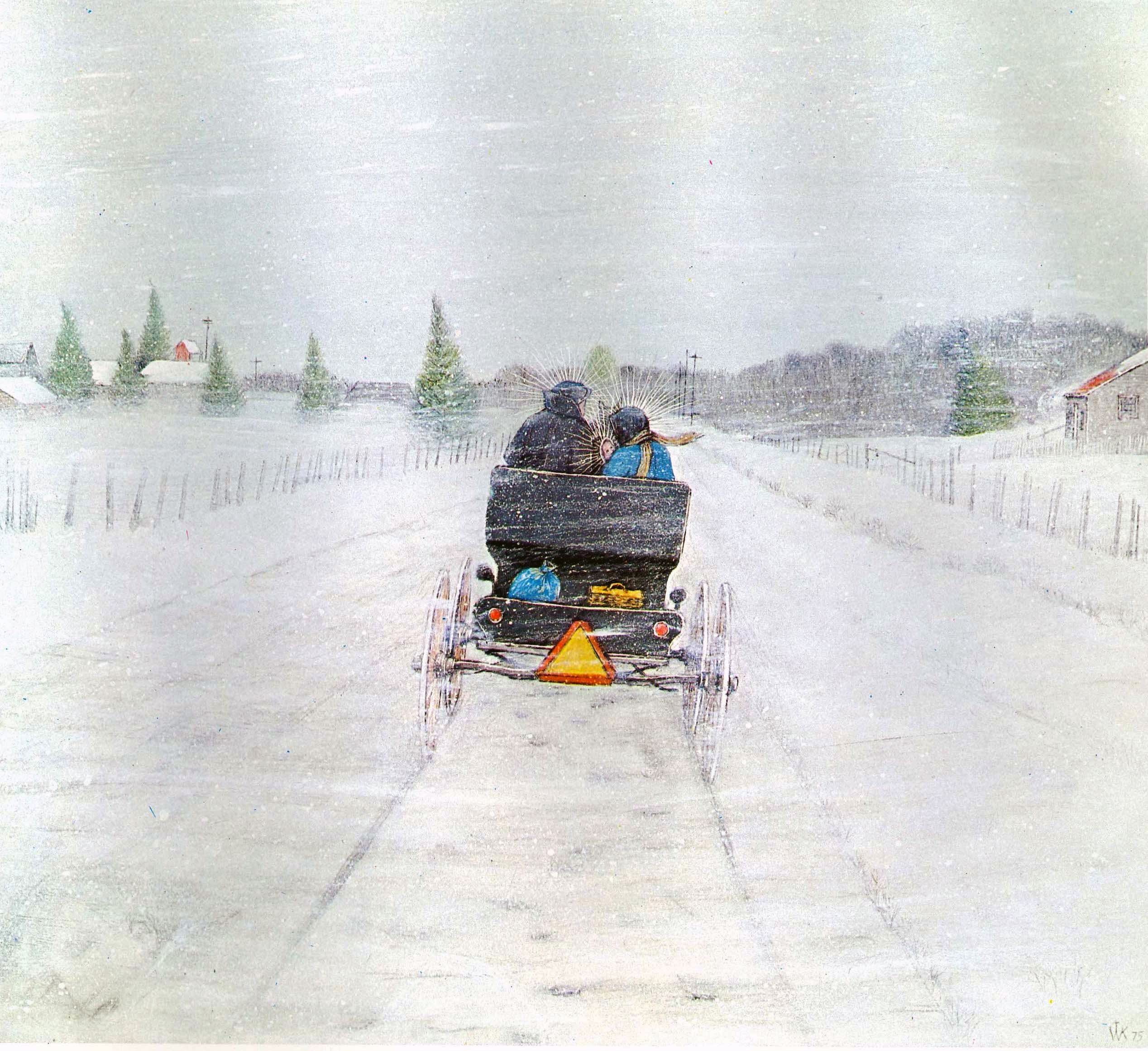

Despite the more than occasional bleakness of Kurelek’s vision, the final two paintings in A Northern Nativity offer some hope. The penultimate illustration, The Welcome at the Country Mission, shows the family pulling up to Madonna House, a lay Catholic mission in rural Ontario, where the inhabitants “hurry out to embrace the newcomers warmly.” (Kurelek visited Madonna House many times.) William notices the Benedictine mandate “Receive every visitor as Christ himself” on the door. Here, again, in an unassuming corner of this enormous country, the family is recognized for who they are. The last painting, Flight into a Far Country, ends the book on a bittersweet note. The family is fleeing the country (presumably for the United States rather than Egypt) down a snow-covered road in a horse and buggy. The baby’s face is just visible as the family begins to disappear into the blizzard. William “tries to run after Them, to beg Them to stay,” but can’t catch them. He hears them say, “We will return one day—when you are ready to receive us with undivided love.” We’re left with the assurance that William will somehow eventually be united with Christ, but, Kurelek writes, William would “suffer much before he was ready for that promised day.”

And, of course, suffer he did. Neither did his conversion solve all his problems. He continued to have bouts of depression, but he was buoyed by his faith and his marriage and family. (Kurelek and his wife, Jean, married in 1962 and had four children.) In the documentary of his life mentioned above, Kurelek says he initially “thought religion was a thing of consolation,” but later came to feel “it was a thing of conviction, like knowing two and two makes four. Feelings are things that come and go. . . . Love may come and go but the marriage remains.”

I will continue to read this book to my kids during Advent, and while I know they’ll enjoy the paintings and the stories, I’m not sure they’ll feel the sorrow that comes from dwelling on one’s regrets. An Orthodox priest once told me we should try to understand our pasts, not regret them. But sadness is an appropriate reaction, I think, to remembering the times we have, as the Anglican liturgy puts it, sinned “in thought, word, and deed by what we have done, and by what we have left undone.”

Christmas is a strange time to be reminded that we, and indeed most of humanity, often ignore what Christ offers.

Christmas is a strange time to be reminded that we, and indeed most of humanity, often ignore what Christ offers : an inversion of worldly power, an invitation to find our selves by losing them, and the initiation of a new heaven and earth where all are welcome and transformed. At Christmas we are meant to be celebrating the in-breaking of a new, divine order. To be reminded, by a children’s book, how often professing Christians ignore or treat this flippantly is jarring and sobering.

With Kurelek, we might be able to dig into this tragic sense of Christmas—to our own daily ignorance and rejection of the incarnation and what it means for our lives. Somehow, this might help us find a home in the world—not to think of ourselves as better than those who don’t “celebrate” Christmas as a religious holiday, but to understand how much we all need the grace it represents, and the contrition it invites.