D

During the pandemic, I taught high school classes at a Jewish day school. For the most part, that meant hybrid teaching—that is, addressing roughly half the class in person, masked and social distanced, and the other half through a screen. Miracles of modern technology facilitated this weird manner of teaching. Zoom and Swivl were two words I’d never used before in conjunction but that now became part of my daily vocabulary. One day I was teaching through my mask and screen and a not entirely rare feeling came over me: no one was listening. I couldn’t be certain because the Zoom students were on mute and, despite my hectoring, their cameras were off, and the faces of the in-class folks were mostly covered, so they looked more like bank robbers than high school students. I tested my hypothesis by telling the funniest joke in my admittedly limited repertoire. No laughs. Of course, I wouldn’t have been able to see any smiles, or hear laughter from the muted Zoom students. Still, not even a body twitch from those in class. I’d lost them.

Time went by. Blessedly, we threw away the masks and stored the Swivls and, through various studies, discovered what had been obvious to any teacher trying to connect through a screen: we hadn’t gotten through. We’d taught almost nothing. It turns out you need full facial connection to teach. The technology solved one problem—projecting my voice and some of my face—but masked the deeper dilemma: creating genuine empathy at a distance.

Years later, still a high school teacher, I returned from winter break to an alarming problem. My most mediocre students were suddenly turning in adequate, even excellent essays. Those were the first heady days of ChatGPT, the new large-language-model artificial-intelligence programs. Much of the world marvelled at the miracle, or fretted over existential issues, like whether these super-sophisticated AIs would steal jobs or kill us all in their quest to manufacture paper clips. But high school teachers and students—canaries in the high-tech coal mine—recognized the more modest threat and promise right away. AI, it turned out, was a great tool for cheating on your homework. Later that month innovation officers at our schools assured us that ChatGPT and its competitors were really no different from calculators—time-saving devices that produce quick answers. What’s 12,367 divided by 43? Compare and contrast the writings of Primo Levi and Elie Wiesel: Why, in your opinion, did one take his life while the other didn’t? Plug and play. Once again, technology solved a problem: it’s midnight, and my essay is due first thing tomorrow, and I haven’t done any reading or research or thinking. But it masked the deeper issue. In an online world of quick takes and short videos, how do teachers facilitate genuinely deep thoughts?

Teaching humans, it turns out, is a more complex endeavour involving relationship, intimacy, face-to-face contact, irritation, passion, and love.

As I reflected on these problem-solving technologies—Zoom with Swivl, and ChatGPT—it occurred to me they both would have “worked” if we’d all been robots. That is, if the goal were to transfer facts and ideas from the teachers to the students, Zoom and AI were the perfect tools. But teaching humans, it turns out, is a more complex endeavour involving relationship, intimacy, face-to-face contact, irritation, passion, and love.

I recalled my depressing experience with cutting-edge teaching technologies recently when a friend sent me a copy of “The Techno-Optimist Manifesto,” by multi-billionaire high-tech entrepreneur Marc Andreessen. The sixteen-page document is a stew of genuinely interesting insights, obvious and uninteresting thoughts, howlingly foolish ideas, and many clearly worrisome notions. For example, the idea that there are only three sources of growth, “population growth, natural resource utilization, and technology,” strikes me as true but also provocative. What exactly does he mean by growth? Are some growths better than others? On the other hand, the theory that “productivity growth causes prices to fall, supply to rise, and demand to expand” is simply Econ 101, a class even I managed to pass my first year of college. The idea that “human needs and desires are infinite” is simple foolishness; we’re not going to need or desire to be transformed into cockroaches or eat lead. Genuinely frightening is the claim “We believe any deceleration of AI will cost lives. Deaths that were preventable by the AI that was prevented from existing is a form of murder.” If citizens seeking to regulate “lifesaving” AI are murderers, they should be severely punished, probably with death. There’s an obvious authoritarian, even fascist, tone to these sentences. Get with the program or you’ll be treated like a deadly criminal.

For me, the most striking quality of the document is the religious language. The first sentence is “We are being lied to,” introducing a kind of gnostic wisdom, where the forces of truth and light battle darkness and lies. The manifesto is replete with “we believe” statements—altogether there are 113—as if it’s mimicking a Christian creed or Maimonides’s thirteen principles of faith. The author promiscuously utilizes transcendent words like “infinite,” “far superior,” “glory,” “forever.” It’s not far-fetched to read the manifesto as a call to form a new religion, where the god is technology and the commandments are to conquer nature, grow, and, above all, get out of the way while the elect develop new, infinitely adept technologies forever.

Fair enough. Anyone in America is free to create new religions, and as I said, not everything in the manifesto is banal or foolish or dangerous. But, given my profession, I was especially struck by the following claim: “We had a problem of isolation, so we invented the Internet.” The sentence is part of a litany of problems technology has supposedly solved: cold with heat; heat with air conditioning; pandemics with vaccines; poverty with abundance. The blustering naïveté in these claims is itself startling. Does the author really think we’ve solved poverty, or that air conditioning is really a solution to global warming? But nothing in this wildly hyperbolic document matches the boast about curing isolation. Technology solves loneliness. With the internet. Andreessen might contest the claim that social media is driving increased numbers of suicides, or that a new generation is losing its sense of empathy because of the internet. But to insist that loneliness is a problem that can be solved by more dependence on technological development flies in the face of pretty much everyone’s experience throughout the pandemic.

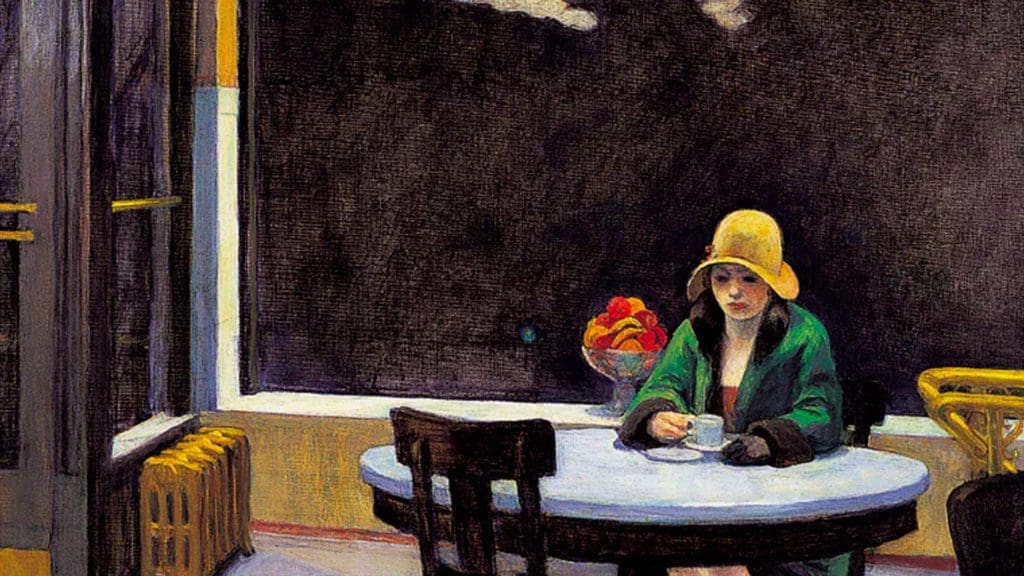

Furthermore, is isolation as a subjective experience—that is, loneliness—something that even can and should be solved? In his classic essay The Lonely Man of Faith, Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik begins with the words, “The nature of the dilemma can be stated in a three-word sentence. I am lonely.” He quickly clarifies, “I do not intend to convey to you the impression that I am alone.” He has friends, family, colleagues, and students. But every so often, Soloveitchik admits, “I feel rejected and thrust away.” Oddly, though, he says, “I also feel invigorated because this very experience of loneliness presses everything in me into the service of God.” The rest of the essay is a plea to embrace loneliness, but only as a dialectical balance to what he calls “the majestic.”

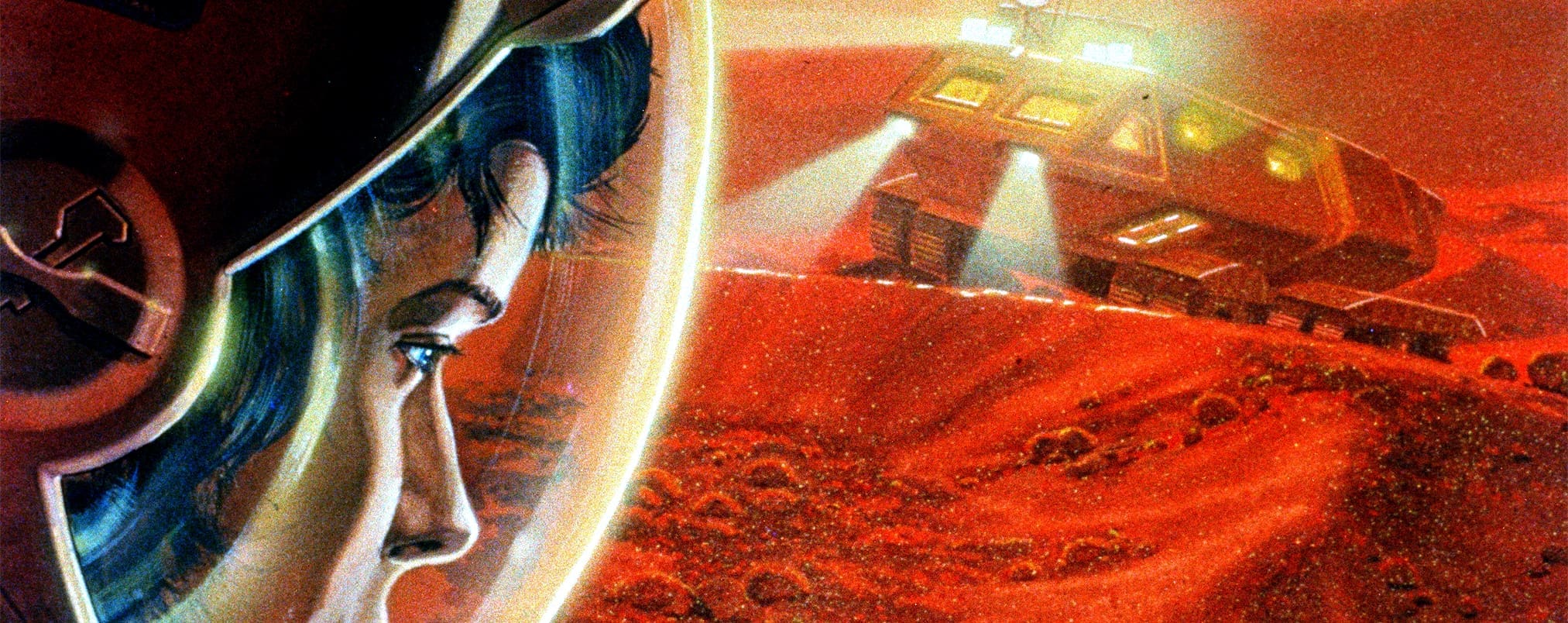

Soloveitchik focuses on the first two chapters of Genesis, noting the two contradictory creation stories and suggesting that the Bible here offers two distinct prototypes, what he refers to as Adam I and Adam II. Adam I is given the imperative to conquer nature, to be “fruitful and multiply, fill the earth and master it, and rule the fish of the sea, the birds of the sky, and the living things that crawl on Earth.” It’s significant that Adam I is created simultaneously with a partner; man and woman burst into being together. “Adam the first is never alone,” Soloveitchik writes. “Man in solitude has no opportunity to display his dignity and majesty, since both are behavioral social traits.” It’s Adam I, with his partners, who builds cities, creates great art, manufactures cars and airplanes, invents air conditioning and artificial intelligence. Since Adam I perpetually builds, creates, and conquers, he’s never alone and never feels lonely. Adam I’s deepest need is for colleagues, not intimate companions.

Chapter 2 introduces us to Adam II, Contemplative Adam, the Lonely Man of Faith. This Adam is put on the earth not to conquer but to protect and care for nature, symbolized by the garden of Eden. Unlike Adam I, Adam II is created alone. Soon he experiences loneliness, which the Bible characterizes as “not good.” God attempts to solve the problem with a series of bumbling gestures, offering Adam various animals. But Adam isn’t looking for mere company or acquaintances or for partners. He’s not looking for colleagues. His existential loneliness can only be eased through intimacy, and intimacy comes with a cost. Adam falls into a deep sleep and loses a rib. For Soloveitchik, becoming intimate “is part of a redemptive gesture” and “must also be sacrificial. . . . This new companionship is not attained through conquest, but through surrender and retreat.” In other words, isolation is not a problem to be solved, whether by the internet or by close partners or intimates. It’s the result of a deep need—a yawning gap that makes us human. And it can only be alleviated, not fixed.

Reading Andreessen’s manifesto after reading Soloveitchik, one gets the sense that Adam I—Majestic Adam, Adam the conqueror, the dignified, the genius industrial artist—emerged whole from the skull of Silicon Valley. I imagine him glaring with irritation at Adam II. The Majestic Adam yearns to tame and exploit the natural world, but Adam II, Contemplative Adam, prattles on about limits, the trees we can’t touch, the apple we can’t eat. The techno-optimist sees elegant, magnificent cures in the tree bark, or technological solutions to hunger in the fruit, or shelter in the lumber, or energy from its burning branches, or maybe even air conditioning. He immediately orients himself toward ingenious exploitation. The techno-optimist is appalled by Contemplative Adam’s stubborn desire to regulate. From the techno-optimist’s perspective, Adam II risks innocent lives by insisting on limits. Maybe, the techno-optimist suggests, we should call Adam II what he is—a murderer.

The religious response to modernity is not a despairing nihilism or a demand for the return to a mythical Eden. It’s a call to embrace the fullness of our humanity, both sides, our ambitions and our quiet prayers.

But Soloveitchik doesn’t dismiss either Adam I or Adam II. For Soloveitchik, these are two sides to the same human personality, two opposing inclinations, two feuding sensibilities. He urges the reader to “embrace the dialectical burden”—that is, to internalize both Adams—the Majestic and the Contemplative. To be sure, Soloveitchik has an agenda. Modern humans in the West, he believes, have leaned too far toward technology—as a source of both material advancement and personal ambition. Even religious institutions, he writes, are filled with ambitious personalities yearning for glory and success. But Soloveitchik’s goal is not to obliterate Adam I. He just wants to reintroduce the notion of sacrificial retreat, of contemplation, of redemptive defeat, into our psyches. He opposes placing success at the pinnacle of human effort. He makes the case for loneliness. His religious response to modernity is not a despairing nihilism or a demand for the return to a mythical Eden. It’s a call to embrace the fullness of our humanity, both sides, our ambitions and our quiet prayers.

Therein lies the weakness of Andreessen’s manifesto. For all its interest and its erudition, it ignores half of what it means to be human. Suppressing Adam II comes with a high cost. Even before its publication, much of our culture had already heeded the commanding voice of “The Techno-Optimist Manifesto.” We became drunk on technological solutions. We spoke to our screens, set up our Swivls, and expected genuine communication. But the internet only tricked us into thinking it could overcome isolation. Modern, technologically savvy teachers, we presumed our students would learn. But no one was listening.