T

In spiritual warfare any recourse to drugs is a sign of failure.

—Olivier Clément

I didn’t want to be god anymore. I wanted God to be God . . . [but] this God could not be trifled with.

—Ashley Lande

The psychedelic revival is in full swing. My fellow Wheaton College alumnus Rob Bell counsels young seekers to try everything—the “whole buffet.” Episcopal priests are all over it (even if the studies they were a part of have drawn very serious criticism from those involved). Without necessarily endorsing the movement, The Christian Century ran a prominent story on the “psychedelic renaissance.” Even traditional Catholics like Sohrab Amari have given psychedelics a riveting, if ultimately debunking, whirl. Promoters describe these drugs as a “cure for atheism.”

For a column titled Material Mysticism, this claim to achieve the “mystical” through such “material” ends had to be addressed. Fortunately, Ashley Lande, author of the engrossing memoir The Thing That Would Make Everything Okay Forever (Lexham Press, 2024), agreed to an interview. Having engaged psychedelic writers like Daniel Pinchbeck and Michael Pollan, I can easily say that Lande’s is the most beautifully written of such accounts. Moreover, as far as I can tell, she laps both of these writers in regard to “trippable hours.” The difference is she promotes the drugs not as gateways to enlightenment but as roadblocks to it.

Matthew J. Milliner: The cynical observer can be forgiven for saying we don’t need another memoir, but the cynic would be wrong, because this book is absolutely necessary. It is not simply an “anti-psychedelic” book, because you very sympathetically convey the allure of the counterculture, what is for many an irresistible siren song. What brought you, a disenchanted psychonaut, to write it?

Ashley Lande: The road to writing this book was definitely a winding one! For years after I quit psychedelics and became a Christian, I felt so damaged by my cumulative years of tripping and so entranced by the person of Jesus Christ that I really wanted to forget all about psychedelics. My interest in telling my story was piqued by reading an essay titled “Ecstasy” by Jia Tolentino in the New Yorker. Her trajectory was essentially the opposite of mine—she was raised in the Christian faith at a megachurch somewhere in Texas, and seemed to credit psychedelics, and ecstasy in particular, with drawing her away from the Christian faith and into what she perceived as greater truth. I had been aware at that point for a while that psychedelics were having a “moment” again, to say the least, and everything I saw about them in the media was overwhelmingly positive without any critical response or counter-narratives. So I wrote an essay for Fathom magazine that was basically a summary of what became the book. It was well-received within its niche, and I thought that was probably the end of it. I had tried pitching another memoir to a number of agents a year or so prior and became disenchanted with the process. I was told (when I did get a response, which was very rare) that my platform was too small and that the Christian market didn’t sell memoirs unless you were Tim Tebow. So I had kind of given up on traditional publishing until Elliot Ritzema, the man who would become my editor at Lexham Press, contacted me on Instagram and asked if I’d submit a proposal to Lexham.

MJM: What about the responses thus far to the book have most surprised you?

AL: I’ve received a number of messages from people who walked the same path I did, and I always love connecting with people like that. I’ve also been thanked by some readers who don’t have any personal experience with psychedelics but recognize the cultural relevance. I think overall what I’ve been most grateful for and perhaps surprised by is how it’s become clear to me that the vulnerability was absolutely worth it. There was a pretty big lapse between when I finished writing the book and actual publication, in part because I had a baby a few weeks after I finished writing it and so we had to put off the final edits and other editorial and marketing matters for a few months. Once the publication date finally arrived, I felt very exposed as I realized friends and neighbours and relatives who had either no or little idea of my “origin story” were ordering and reading it! But the responses I’ve gotten have been overwhelmingly positive, and many of them deeply meaningful.

MJM: Seven volumes of brilliant scholarship from Bernard McGinn have been penned precisely to pry Christian mysticism away from the category of mere “experience.” Similarly, I could not help, reading your book, being deeply grateful for the gift of mere sobriety and the level of consciousness that is readily available to us. Still, your book strikes me as not about the denial of experience but about moving into a deeper level of experience, including pain, suffering, and a sense of our own limitations and sin. Do you agree with this assessment?

AL: Absolutely. It’s ironic to realize now, especially considering the bad trips I had, that my psychedelic voyaging was actually a very escapist endeavour. It carried me farther away from authentic relationship, farther away from being in an incarnated body, farther away from the reality that God has ordained. And the reality that God has ordained is often saturated with tedium and suffering. Life is hard! I was reading in Ecclesiastes today—a book I understand more and more as I age—and these verses struck me: “What do workers gain from their toil? I have seen the burden God has laid on the human race.” And yet this is followed directly by “He has made everything beautiful in its time. He has also set eternity in the human heart, yet no one can fathom what God has done from beginning to end.”

I always remember an incident years ago when I was still immersed in psychedelic use and working a temp job. I became acquainted with an older couple, likely nearing retirement, who worked at the same firm. They were very sweet and obviously devoted to one another—they always ate together quietly in the lunchroom, sharing sandwiches from the same lunchbox. After I had failed to get a permanent job there and moved on to another temp job, I ran into the man at the dentist. We exchanged some small talk, and I expressed to him my disappointment that I hadn’t gotten the permanent job at the firm. He simply replied, “You’ll have many disappointments in life.” I just kind of smiled and nodded, but inwardly I recoiled. I was twenty-five and newly married and life seemed brimming with promise and I was awash in entitlement; the world owed me everything for being young and beautiful and ebullient (part of that ego inflation of psychedelics!). Now I recognize his wisdom—yes, life is full of disappointment, but if we cleave to Jesus Christ, that disappointment drives us more deeply into the mystery and riches of his love and grace.

As I write in the book, my psychedelic use and embrace of new age and yogic philosophy also didn’t have a category or means of understanding suffering, either my own or in the world. The incarnation, crucifixion, and resurrection of Christ is the only story big enough to carry the weight of the brokenness of the world. There is simply nothing else that can and no one else who can.

MJM: Psychedelic literature has its own canon, and you describe your absorption into it in detail, including Alan Watts (whose life, as I have detailed elsewhere, did not end well). What would you say to those who have not yet read your book but who are drawn not to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John but to Aldous Huxley, Philip K. Dick, R.A. Lafferty, and Ram Dass instead?

AL: Indeed, Watts’s life didn’t end well. It really saddens me. And I think you do have to look at the fruit of someone’s life and more specifically where their philosophies and beliefs led them. I still have some fondness for PKD and Ram Dass, but Dick was a speed freak and his personal life was a terrible mess—he married and divorced five times. Aldous Huxley was associated with all kinds of unsettling and nihilistic ideas, and specifically hoped (along with Timothy Leary) that psychedelics would undermine traditional Christian sexual morality—indeed, a trip he took with his son and daughter-in-law effectively ended the latter’s marriage, which was perhaps not his intention but exemplified the supposedly “liberating” power of LSD that in fact often leads to relational ruin. And Timothy Leary . . . well, there’s zero nobility in hiding your drugs in your kid’s underwear to try to evade detection, not to mention the bizarre obsession with the internet he developed at the end of his life, among other beliefs. He’s a prime example of how acid inflated rather than “killed” an ego.

So I suppose I would say, look deeper into the lives and philosophies of these apparent “heroes.” But at the same time, the fruit of one’s life doesn’t necessarily determine the truth of what they are preaching. You have people such as Brennan Manning, whom I love, who struggled with alcohol addiction. And more egregiously, you have figures such as the Christian apologist Ravi Zacharias, who committed grave sexual offences for many years before his death and never appeared to repent or confess. But the difference is that Zacharias was a supreme hypocrite in addition to being a predator—Christian morality is the standard he preached, and he failed grievously. With psychedelic figures, there is no such standard—Huxley himself said he had much riding on the idea that life was meaningless, because it gave him sexual license—and so I think it’s reasonable to examine the logical outworkings of their philosophies and psychedelic use in their lives and at least somewhat judge the philosophies accordingly. Did their ideas that psychedelics would lead to enlightenment play out in their lives? Did their psychedelic forays actually provide answers to suffering, to meaning? Did any of it really provide solid ground on which they could stand? And while a lot of what Ram Dass and Alan Watts and others would say sounded sophisticated, when you break it down or “scale” it to a foundational level, does it really work? Does it even mean anything at all?

MJM: You burned out on generic rhetoric about “the Universe.” Indeed, your conversion took you from a “nameless characterless All” to a God with a name. Huxley said that all mysticism boils down to the same advice offered by golf and tennis coaches, to simply “combine activity with relaxation.” However, that could apply as much to training a sniper as it does to training someone in the love of neighbour. You were instead drawn to the specificity of Christian revelation. “And with terrible specificity came accountability, came inescapability, came a piercing intimacy.” Can you expand on how Christian specificity differs from generic psychedelic approaches to spirituality?

AL: It all comes down to the person of Jesus Christ and how he, and only he, can answer the dilemma of being human. Generic platitudes about embracing the dark and the light or claims that “the Universe will give you what you need” reveal their vapidity in the face of actual suffering. And further, you begin asking, “Well, exactly who or what is ‘the Universe’? What is its character? What kind of agency does it have? What is its nature? Is it a deity or just a vague collective energy, and in the case of the latter, how is there any agency or intention at all?” As I said earlier, it just can’t carry the weight—the burden of being human, the need we have for an absolute ground of meaning, and the endless questions that being human entails. The generic psychedelic approaches are unsatisfying at best and profoundly insulting at worst. I couldn’t imagine telling someone who’d lost a child, for instance, to “embrace the dark and the light” or “you’re only suffering because of your attachments.”

MJM: Michael Pollan and others would appear to claim that “ego death” is the common ground between what drugs offer and what religions like Christianity do. But you say Christian ego death, unlike the kind of death counselled by Ram Dass, is different. “LSD’s death was harsh, even punitive. This [Christian] revelation was unspeakably, soul-cleavingly tender.” I loved this passage so much. May I ask you to expand on that a bit more?

AL: The irony of psychedelic ego death is that it often has the opposite effect—the ego becomes inflated, delusional, convinced of its immortality and superior grasp on some kind of esoteric meaning beyond meaning that the inexperienced do not possess. It can also have the effect of shattering someone’s psyche entirely—I’ve been haunted and also heartened by a message I received a couple of years ago from a young man who watched me on a podcast and said he was encouraged that I appeared psychologically intact after tripping as much as I did, because he’d had a traumatic LSD trip a year prior and was still struggling to regain his stability. I don’t know why God preserved me, but I can only get on my knees and thank him for it! I certainly didn’t deserve it, and it grieves me deeply to know there are those who mentally do not come back from psychedelic use.

Additionally, in psychedelic ego death, the only sin is the ego—having one, or the illusion of one. But as I continued using LSD and supposedly endured one ego death after another, my awareness slowly grew that something wasn’t right within me. The “cure” was indeed not curing me at all. I didn’t feel clean, I didn’t feel purified, despite there being a kind of harsh “born again” feeling to many trips that I now believe is a pale simulacrum (and perhaps even a satanic mockery) of true rebirth in Christ. Although a piercing awareness of my sin and brokenness and utter inability to save myself, when it came, was devastating, the cure that Christ offered was the sweetest nectar I’d ever tasted. It was the good that was too good to be true, but indeed was. And yes, it was tender, and shockingly beautiful. The psychedelic ego death also felt as though it fractured me into a thousand pieces, but the revelation of the gospel began to make me whole. Jesus offered a refuge from the knowledge I’d been chasing; he relieved me of a burden I was never meant to carry. I think it was also incredibly healing to me to know that there was no place I’d been on psychedelics, however harrowing, however dark and desolate, that Jesus had not been and over which he was not Lord. And he was not afraid. I knew I never had to go back to those places once I quit psychedelics, but they left a scar. It’s hard to put into words, but that was important to me—I really believe a bad trip is a burden that the human psyche is not meant to bear, but Jesus was not afraid of those places as I was.

MJM: To cite Brian Muraresku, author of the bestselling book The Immortality Key, psychedelics have been kept from us due to a “truly global conspiracy” about the psychedelic origins of Christianity, a fact that was suppressed “to rob Christians of the beatific vision.” Freed from the “jackboots of the Roman Catholic Church,” we can now all experience the entheogenic “Reformation to end all Reformations.” Or, actually not. Enthusiastic Joe Rogan and Jordan Peterson interviews with Muraresku notwithstanding, Muraresku’s claim is just not true at all. Might criticisms of Muraresku, or the thoughtful considerations of Joe Welker and others, slow down the movement, or do you think the new enthusiasm for psychedelics is an unstoppable force?

AL: As you say, Muraresku’s assertions have been expertly debunked by a number of people, including my friends Joe Welker and Paul Anleitner. I’ve never bothered to read Muraresku’s book—it just sounds so silly, and his assertions aren’t new—so I’m thankful others have trudged through it and analyzed its claims so I don’t have to! I actually think the enthusiasm is slowing a bit—I read that the attendance at one of the largest psychedelic industry events was significantly lower this year than in years past. I think people are perhaps slowly realizing that psychedelics simply cannot deliver on the promises their proponents aver, and a gradual disillusionment is taking place. That makes me really hopeful because I think psychedelic disillusionment means that people will still be searching for transcendence and for truth, and maybe there will be a movement toward Christ. Justin Brierley does a lot of good work in documenting the revival of interest in Christianity that he sees in numerous spheres, and I hope that disenchanted psychonauts will be a major one of those contingents.

MJM: One of the most chilling moments of your book was how you encountered sheer evil exterior to your psyche (as confirmed by your equally terrified dog) following, but not during, a trip. In addition, your encounter with beings that are sometimes called “machine elves” matched the exact description that you read in other trip reports. This opened you to the reality of evil, which most psychedelic enthusiasts seem to have not (yet) grappled with. Who, or what, do you think those beings were?

AL: I absolutely believe they were spiritual beings, and that psychedelics open us up to the spiritual realm in ways for which we are totally unequipped. And I would say that many psychonauts who have tripped more than a handful of times (and some who have only done that) have in fact been faced with the reality of that evil but have perhaps been able to rationalize it with psychedelic philosophies such as “There’s no such thing as a bad trip. ” This is the idea that bad trips only occur to teach you something, or that they’re only a reflection of yourself, or the resistance of your ego to death, or that the “shadow” you experience is in fact something that should be embraced in the interest of integration—all of those terms I now roll my eyes at because it’s so shallow and gaslighting.

Terence McKenna, for instance, who is one of those giants within the psychedelic world and is often referenced by Rogan, had a terrifying mushroom trip toward the end of his life. His brother, Dennis, says that Terence was horrified that “the mushroom,” who was practically a deity of its own to him, had betrayed him and shown him the essential meaninglessness behind all things. From what I’ve read, it seems like it really spooked him. Yet that doesn’t seem to be part of the lore around McKenna because it doesn’t fit the narrative—it doesn’t seem to be something that McKenna himself was forthcoming about—and I wonder if it was because he’d built his entire life and persona around psychedelics and especially psilocybin. So that evil is often downplayed or outright denied in the psychedelic world, and I feel as though this is at least in part probably the work and influence of the entities themselves. Satan indeed masquerades as an angel of light.

MJM: One of the Bible verses that embarrasses some Christians is “women will be saved by child-bearing” (1 Timothy 2:15). I could not help but think of that verse reading your book, both because your child-bearing experience helped save you from the false promises of psychedelics and because—owing to a cultish birthing seminar you attended—you experienced the elevation of natural child-bearing to an oppressively puritanical religious code from which Christianity set you free. In addition, it was the death of a toddler, and the way a Christian couple helped navigate that tragedy, that helped wrench you from the false consolation of psychedelics. How has your further experience as a parent informed this realization?

AL: I love this question, because I’ve given birth twice more since I finished the book, and had quite different experiences from what I chronicled there. Of course, I suppose Paul didn’t mean that verse literally—because men and women alike are saved by grace through faith alone, and obviously God is still very much capable of saving women who never bear children—but child-bearing has absolutely played a huge ancillary role in my salvation, even after I converted, in reminding me in a very dramatic way that Christ can be counted on. There’s also a death-rebirth aspect of childbirth for the mother that I think is very much by God’s design, not to mention the sacrifice inherent therein. I also saw a tweet just after I gave birth most recently (to our fourth baby and second daughter) that I loved—it was by Tara Leithart and she said, “Lent hits different when you’re due to give birth Easter week,” which is certainly true. But the one that really hit me was the follow-up tweet of “Finished this off with a Holy Saturday birth. A descent into hell to free a captive, you might say.” The pain of birth is hellish. The contrast between that and the bliss I’d been groomed to expect by the New Age world was deeply jarring, but as I wrote in the book, the dissonance absolutely contributed to my questioning and indeed my eventual salvation. And God is so faithful—for my most recent birth, I returned to home birth, which is something I never thought I’d do again. Yes, the pain was immense, but God was so kind to give me an experience I hadn’t yet had—once she was out, the pain was completely over. I marvelled at it. It was nothing like the birth of my first daughter that I’d written about, where I felt so shell-shocked that I couldn’t even look at her for a while—but even in that birth, God had great purpose, and of course I got my daughter out of it! I hesitate to use the term “psychedelic” in any kind of a positive way, yet I’ve had the thought that birth is psychedelic in a way that the “best” trip can only ever mimic, and very poorly. It’s holy and sacred and beautiful and bestial and full of suffering and kind of horrifying, but also deeply human and deeply worth it, many times over. God has taught me lessons through child-bearing that I never could have learned through psychedelics, or meditation, or yoga, or anything else.

MJM: A lot of people seem unaware that Huxley was condemned by his own Indian guru, Prabhavananda, for moving from disciplined Hinduism to psychedelics. And yet some people (falling short of the wisdom of Prabhavananda) seem to think they can mix psychedelics with Christianity—not as a one-time healing experience but as a regular thing. What would you say to them?

AL: There is so much to say, and a lot of it has been covered by others. My friend Joe Welker has written about this, and a good book on the subject of why the two are incompatible is The Return of the Dragon by Lewis Ungit. It’s also covered a bit in The Transhumanist Temptation by Grayson Quay. It’s really alarming how deeply transhumanism and psychedelics are intertwined, especially among tech elites. That link in itself is a reason to look askance at the whole business. Recently a seminarian contacted me because he’s conducting research on psychedelics and hoping to demonstrate that they are a “common grace” to be used cautiously. I disagree—I think even supposedly judicious use won’t end well, because inherent in the premise is the idea that we can use these substances judiciously, that we somehow control them, and we simply don’t. We don’t control where they take us because we don’t control the spiritual forces that can and do work through them.

This same student mentioned that he is frustrated with the conflation of psychedelics themselves with “psychedelic culture.” I invited him to consider why he disliked or found distasteful the culture that has organically arisen around psychedelics, and further consider why that culture is the way it is. I’d say it’s the way it is because of psychedelics! Psychedelic use gives rise to psychedelic culture. Sure, there are many subcultures within that culture, but I’d say a common thread is a disdain for Christianity. That’s a major irony with Christians who are seeking to wed the two—by and large, psychedelic culture hates Christianity. There’s a reason for that. Yes, you’ll very occasionally find the odd testimony where someone became a Christian after a psychedelic experience, but I’ve observed that even among those testimonies, they pivot on the idea that God chose to speak to them while they were on a drug, usually not that the psychedelics themselves occasioned a revelation of the gospel. Some might claim that’s splitting hairs, but I’d argue that there is indeed a distinction. Regardless, those are the extreme minority. Far more often, psychedelics cause people to abandon prior Christian beliefs, or embrace something that they may still call Christianity but that has very little resemblance to any kind of Christian orthodoxy. Usually it’s a kind of vague pantheism that denies the exclusivity of Christ. But I think my main advice—besides mentioning the biblical prohibitions against pharmakeia—would be that you do not control this, and it will take you somewhere you didn’t want to go and didn’t expect to go, even if it seems benign or even enriching at first. Instead, take heart and wait on the Lord. Don’t try to force your way to transcendence or revelation; don’t build a psychedelic Tower of Babel—it can only end in ruin.

MJM: This is a fair point, but what about, for example, the controlled use of ketamine in a therapeutic environment? I have a Catholic friend who has done this owing to a medical condition, but he was quick to say that to compare the experience to prayer would be blasphemy. While neither of us are physicians, what are we to make of the possible medical benefits?

AL: I find this particular avenue of questioning in regard to psychedelics most difficult to respond to, primarily because it’s kind of impossible to refute someone’s subjective experience of healing or improvement in depression, anxiety, PTSD, or other psychological disturbances. But I would point to many, many cautionary tales where psychedelic therapy in fact made the patient’s symptoms far worse, or created new iatrogenic symptoms and afflictions as a direct result of the “treatment.” And while it’s easy to say and even truly believe that we are internally transformed, we see in the Bible and specifically the New Testament that transformation is lived out in Christian fellowship. To people claiming they are nicer, kinder, more patient, more loving after psychedelic use, I would ask, “To whom are you accountable? Do others observe these changes in you?” I would’ve claimed the same during my heavy psychedelic use, and I also claimed I’d attained some level of “healing.” In reality, the rot of my sin was as deep as ever, and as the years went by, I could no longer deny it.

There’s a reason people use dramatic terms to describe psychedelic experiences. Years ago, I read a book titled Breaking Open the Head by the psychedelics enthusiast and self-styled guru Daniel Pinchbeck, whom you mentioned above, and who has sadly himself admitted to predatory behaviour. The book was terrible, but I felt the title was very apt. It is true that for many people—perhaps most—the effects of psychedelic experiences cannot be undone. Many “psychedelic scientists” would agree that psychedelics “rewire” your brain, although they would consider these effects potentially very positive. I find it terrifying, considering how uncontrollable a psychedelic experience really is, and in the years since I quit psychedelics, I have had to remind myself often that the Lord himself promises I will be transformed through the renewing of my mind by him! For years after I quit, I would still have occasional flashbacks, usually if I woke up in the middle of the night. I would pray or just call on the name of Jesus until they faded. Compared to many others, I escaped relatively and miraculously mostly unscathed from my years of use, but I still wonder at times if I permanently damaged myself in subtle ways from how much LSD I took. I just can’t dwell on it, though—I have to choose to rejoice in the Lord and trust.

So my posture toward even so-called therapeutic use of psychedelics is highly skeptical. These therapists like to claim that a “controlled environment” and therapeutic guidance offset the odds of really, really bad trips, and perhaps that is true to an extent—I imagine they have sedatives on hand to mitigate total panic—but control in this realm is truly an illusion. Not to mention many psychedelic therapists are steeped in Buddhist spirituality, which, at least in America, has a veneer of being a kind of “neutral” spirituality, but of course has its own convictions and worldview. I fail to see how therapists can abstain from imposing their own spiritual views on patients—which may also be true of therapists who only practice talk therapy, but therapists who administer psychedelics to their patients are dealing with people in a highly vulnerable and impressionable state. And that’s potentially very dangerous.

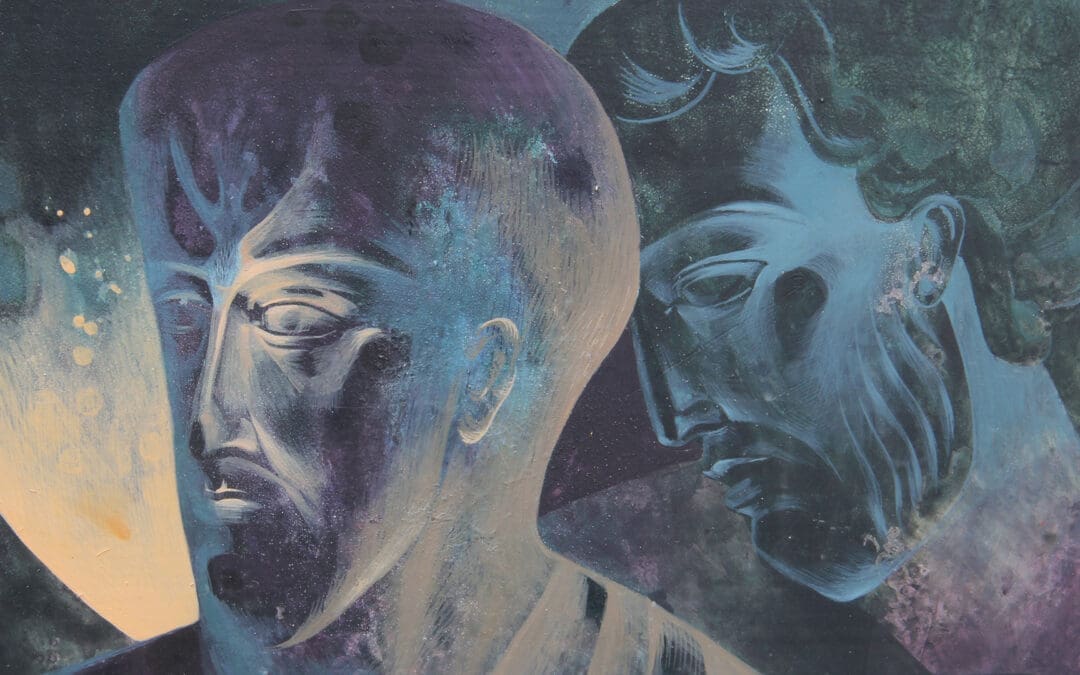

“Easter Everywhere” (2016), pencil, coloured pencil, and gold leaf, by Ashley Lande.

MJM: The fact that you continue psychedelic-style art even as a Christian suggests to me that there are aspects of the counterculture that are in fact redeemable. Is that too positive a way of putting it?

AL: I don’t think so! The way I think of it is through the lens of Romans 8:28: “In all things, God works for the good of those who love him and are called according to his purpose.” I’ve always been drawn to colourful, intricate patterns, even before I used psychedelics. Interestingly, when I was actively taking psychedelics, my artwork was very dark, in both theme and style. I feel God has redeemed that aesthetic in my work and made it orderly according to his patterns in creation. Yes, you can see mandalas and intricate patterns while on psychedelics—but mandalas and intricate patterns exist in God’s creation. It’s not like psychedelics have an edge on the beauty inherent in God’s design. I’ve often heard it said that Satan has no originality of his own—he can only attempt to corrupt what God has already created. My artwork when I was taking psychedelics would often have intricate patterns, but it was chaotic and fractured. Psychedelics don’t “own” geometric designs—and the prevalence of things like “sacred geometry” in New Age / psychedelic circles now appears to me as a prime example of “worshipping the created things instead of the Creator,” as Paul says in Romans 1:25. These things are not ends in themselves but part of the beauty of God’s design, and I hope and pray that when they appear within my artwork, they point the viewer back to him.

MJM: What would you say to the psychedelic-curious Christian who has not yet read your book but who thinks psychedelics might resolve their doubts about the spiritual realm?

AL: They won’t solve anything—only amplify and compound confusion. God can and should be trusted—we don’t need to eat the fruit of the forbidden tree, and the forbiddance is a protection, not an arbitrary rule. Although God has brought me very far in healing me from my experiences, I bear scars from some of my trips that I know won’t be fully healed until eternity. They don’t haunt me as they once did, but there are certainly things I’ve felt and seen on psychedelics that I absolutely wish I could completely blot from my memory. One of my very favourite psalms (and one of my favourite Scripture passages in general) is Psalm 131. I think of it often, in relation to both my past and my present strivings to “know” more than God has allowed, and I would refer any psychedelic-curious Christian to it as well:

My heart is not proud, Lord, my eyes are not haughty;

I do not concern myself with great matters

or things too wonderful for me.

But I have calmed and quieted myself,

I am like a weaned child with its mother;

like a weaned child, I am content.

O Israel, put your hope in the Lord

both now and forevermore.

MJM: Amen. Thank you, Ashley, for answering these questions and for writing this beautiful book!