H

Traditionalist Trapping

Heresy hunting, I’m afraid, may be a necessary occupation. There are those who claim the name Christian—and its market share of book sales, ministerial roles, and (dwindling) teaching positions—while purveying an altogether different product. The New Testament, and Christ himself within it, warns about false teachers repeatedly; it is therefore not necessarily prudish or reactionary to call them out. Christian disunity, it needs to be added, complicates the heresy hunter’s task considerably. Even so, finding and even exposing those who disseminate something less than Christian while claiming to represent Christianity, unfortunately, remains a required task. But God help those who enjoy the hunt.

Being neither bishop, college president, nor formal theologian, I have come to prefer a different occupation than heresy hunting. I reverse the enterprise and, to keep the alliteration, call it traditionalist trapping. This entails going after those who some assume to be patent heretics and showing the accused to be far more traditional than they may at first appear. Please spare me the line from Jaroslav Pelikan that “traditionalism is the dead faith of the living; tradition is the living faith of the dead.” When I say I enjoy traditionalist trapping, I don’t mean I am hunting those whose faith is dead, but simply those whose faith is far more tried and tested than book publishers, always eager for an edgy take, might suggest.

The first thing to say about this occupation is that it is rarely successful. And like hunting or trapping in the actual wilderness, traditionalist trapping can be a wearying enterprise. Patience is everything. One must go well beyond newsletter subscriptions and YouTube clips and, instead, read the target author’s books—even all of them. I tried it once in these pages with Richard Rohr, and it took me the better part of a decade. The task does not entail ignoring, still less endorsing, errors; rather, it involves unearthing a possibly latent orthodoxy or pastoral effectiveness that more noticeable errors—rightfully seized on by skilled and legitimate critics—sometimes occlude.

Spong’s Blunder

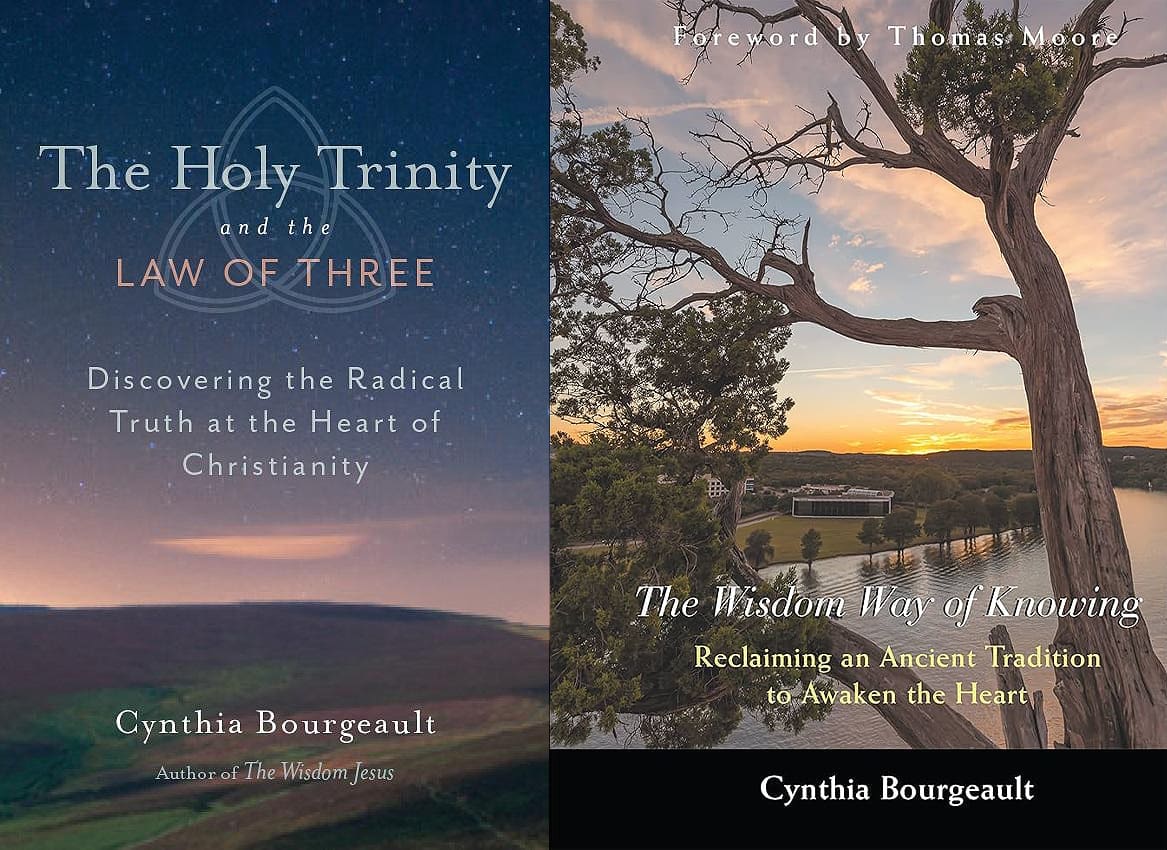

But like effective heresy hunters, we traditionalist trappers are never satisfied with one. And so, for a half decade or so, I’ve been on the trail of another faculty member at Rohr’s Center for Action and Contemplation, the Episcopal priest Cynthia Bourgeault. For all the recent talk of “wild” Christianity (whether Paul Kingsnorth, Martin Shaw, Michael Martin, or Nick Cave), Bourgeault might be the wildest of them all. But my intuition has long been that Bourgeault is not the renegade that the expressly heretical “bishop,” the late John Shelby Spong, claimed her to be. Prominently emblazoned on one of her books, The Holy Trinity and the Law of Three, is Spong’s claim that her “masterful and insightful” book “opens the door to a trans-Christian vision.”

For all the recent talk of “wild” Christianity (whether Paul Kingsnorth, Martin Shaw, Michael Martin, or Nick Cave), Bourgeault might be the wildest of them all.

My suspicion is that, like many endorsers, Spong did not bother to carefully read the book he endorsed. For it begins with a chapter titled “Why Feminizing the Trinity Won’t Work,” in which Bourgeault effectively eviscerates those, like Spong, who insist that Father, Son, and Holy Spirit language is “so male, so dated.” Before the book’s end, Bourgeault thoroughly undermines what is called “the perennial philosophy” (a tasteless mishmash of all religions watered down to thinnest broth) in favour of an incarnational Christian vision, and she endorses the intuitive metaphysics of the church fathers, even if (knowing her readership) she first has to apologize for doing so. The result is the delicious irony that America’s most famously heretical bishop has “endorsed” a book that contains these words:

If the greatest of Christian mystical theologians—including the Cappadocian fathers, Saint Augustine, and Saint Bernard of Clairvaux—have drawn living water from [the traditional Christian well], who am I to suggest [as, incidentally, Spong has] that the well has run dry? But you see, that’s exactly what I’m not saying. In contrast to what is now a growing majority in liberal theological circles, I have stated emphatically, and will continue to state emphatically, that there is nothing amiss in our familiar model. I repeat: there is nothing amiss. The “persons” [of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit] are correctly named and configured, and nothing needs to be amended.

These are the passages we traditionalist trappers live for. At the very least, it justifies our peculiar book purchases. That said, classical Christians who pick up The Holy Trinity and the Law of Three in search of such riffs will be faced with a whole lot of, for lack of a better term, weirdness. To best understand such puzzling (if frequently insightful) excurses, and Bourgeault’s need to include them, we need to look at her lifelong trajectory.

She relates her journey clearly in an early publication, The Wisdom Way of Knowing:

As a child growing up in Protestant America in the fifties, I spent most of my young life feeling stranded and disoriented, like a space traveler landed on an alien planet. The first real relief and sense of direction came on a trip to France the summer I was eighteen. I walked into Chartres Cathedral and was completely magnetized. The profundity, beauty, and Mystery I experienced there propelled me toward medieval studies as an academic discipline and toward Catholic Christendom as my spiritual home. . . . Graduate school and then ordination in the Episcopal Church ushered in the next twenty years of my life, which were really a spiritual seesaw. While I loved the liturgy and devotional aspects of the church, I also felt there were huge holes in its theological understanding and its practical teaching on spiritual formation.

No surprise there. She is, after all, referring to the tradition that gave us Bishop Spong. But then things take an unexpected turn. Bourgeault finds herself involved in one of most sophisticated, arcane, elusive, and demanding concatenations of what is loosely termed the “New Age” movement—namely, the work of G.I. Gurdjieff (ca. 1867–1949), who transmitted to modern audiences, for better or for worse, the Enneagram. Bourgeault continues:

That [Christian deficiency in practical teaching] propelled me toward esoteric work. I found my way to a Gurdjieff group . . . to which I belonged, on and off, for nearly a decade. There, however, I experienced the exact mirror image: the missing cosmological and practical teaching were all in place, but minus any sense of reverence or devotion.

The practical failures of Christianity sent Bourgeault to Gurdjieff circles, but the devotional failures of such circles sent her back to Christianity. This is not the place to expand on what this demanding form of spiritual attentiveness—what Gurdjieff’s followers call “the Work”—entails, or on Gurdjieff’s philandering with his students, or to examine those who excuse his indiscretions today. Bourgeault describes the Work simply as “an early run-up to what we would now call ‘mindfulness training,’ combined with an intricate cosmology and even more intricate metaphysics that has continued to intrigue the more nerdily inclined.” Suffice it to say here that a famous Gurdjieff follower, the philosopher Jacob Needleman, played a large part in helping Bourgeault find her way back to some form of the church. His classic and astonishingly good book Lost Christianity essentially makes the case that Christianity already has a rich tradition of practical mysticism that Christians are failing to access. Still, it was not Needleman but another important player who put it all into concrete practice for Bourgeault.

[The] two halves of the puzzle [Gurdjieff and Christianity] finally came together when at Saint Benedict’s Monastery in Snowmass I met my teacher, a hermit monk who had fused the esoteric and Christian mystical tradition with his own being and could teach me from a place of real understanding. After that immersion, I went back to both my Christian and my esoteric sources and found I could read them with a new heart.

This is an important point. If Christianity is not just a teaching but a person—our Lord Jesus—it follows that Christianity will never entirely make sense until it is convincingly enacted in the lives of persons as well.

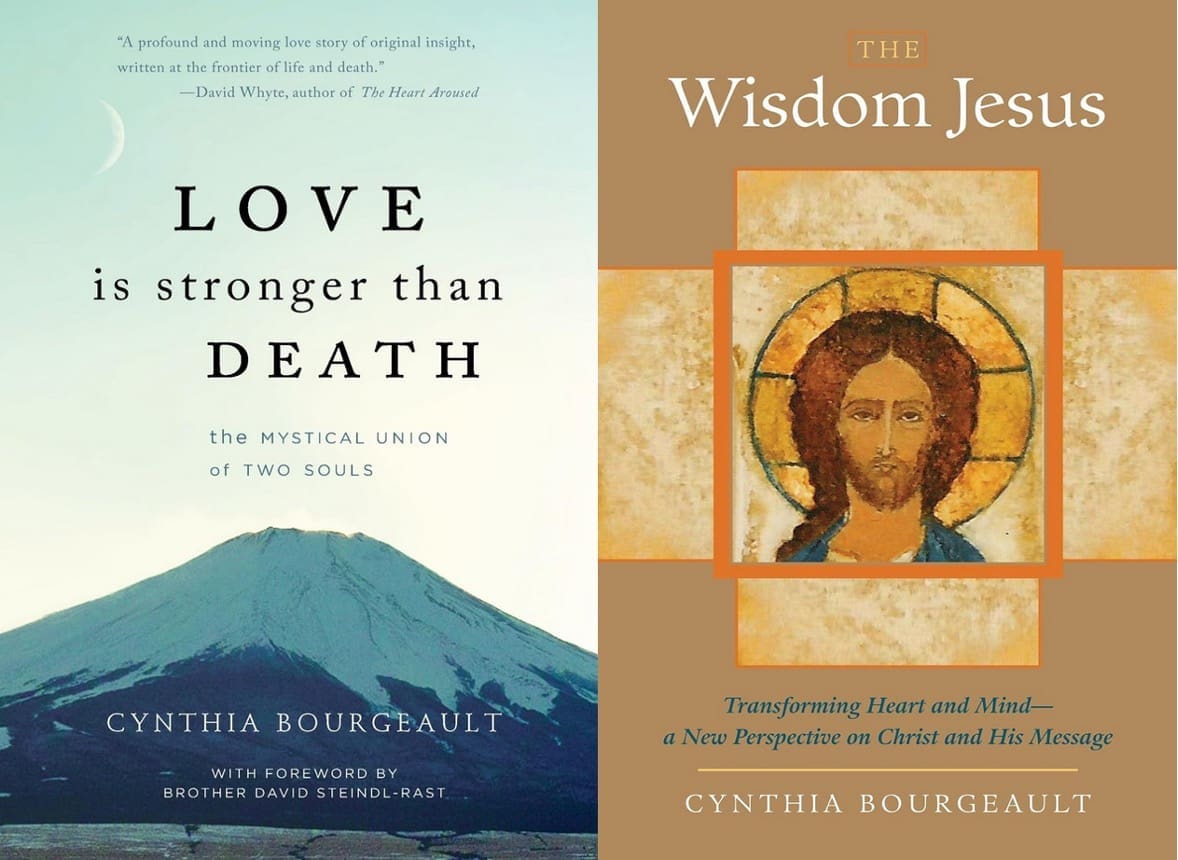

Soul Mates

That person’s name, for Bourgeault, was Brother Raphael Robin, a septuagenarian Trappist hermit who finally initiated her, twenty years his junior, into the rigours of lived, conscious, sacrificial Christian spiritual life. Which is to say, here was a monk able to fuse the demands of Gurdjieffian attentiveness—which “Rafe” (as Bourgeault came to know him) refined in the painstaking process of fixing snowmobiles—with the formalities of Benedictine monasticism. Bourgeault tells the story of their spiritual partnership in one of her wildest books (and that’s saying something), Love Is Stronger Than Death. Those who suspect something untoward might be afoot, or that this might be a full-scale affair, will find their suspicions unconfirmed. On the contrary, Bourgeault’s book contains a gorgeous affirmation of the gift and vocation of celibacy:

Celibacy must be purified of avarice and self-protectiveness; that part which would hold itself back from complete self-giving in order to protect its own spiritual self-interests. . . . That was the “narrow spot” Rafe and I always found the most challenging to negotiate: how to embrace a celibacy that was not at the same time a withholding of self, a flight into holiness; but was a complete and shared realization of “everything that could be had with a hug.” But it does exist.

The spiritual bond between the two of them, it seems, was profound enough to not require sexual expression. Furthermore, Bourgeault claims, the bond has outlasted Rafe’s own physical demise. Bourgeault beautifully relates an abiding, continual contact with Rafe that is far deeper than grief-induced nostalgia. This may be the part of the book most difficult for readers to fathom, unless they have had similar experiences. Rest assured, Bourgeault is crystal clear that what she is describing is not necromancy, which comes with great spiritual danger. The continuation of her relationship with Rafe is not an achievement, still less a conjuring, but pure gift. What I think she is arguing for, in fresh and admittedly provocative language, is the traditional understanding of the communion of saints. “He is not the God of the dead,” said Jesus, referring to long-departed patriarchs, “but of the living” (Matthew 22:32).

Because Gurdjieff speaks of developing a soul that can outlast the body, one can be forgiven for assuming all of this is guided less by Christianity than by a dangerous form of esotericism. But the catch is that Bourgeault herself shares those same suspicions. If she is a heretic, she is a Gurdjieffian heretic. “I am unwilling,” she insists, “by my own Christian roots, to take the view that Gurdjieff took by assuming such a soul [who has not undergone “the Work”] is annihilated.” In the same book she offers a careful, experientially grounded dismantling of belief in reincarnation. In effect, what we see here is not “cafeteria Christianity” (picking and choosing from among Christian doctrines) but “cafeteria esotericism,” as she picks and chooses from esoteric systems to make up for the perceived deficits of a not-always-street-smart Christian faith.

Wisdom Christianity

Maybe the most comprehensive introduction to Bourgeault’s Benedictine fusionism comes in a later book titled The Wisdom Jesus, which is kryptonite for enthusiasts of the so-called Gnostic Gospels championed most popularly by Elaine Pagels. In it Bourgeault corrals interest in the non-canonical texts back toward their canonical counterparts. The “Wisdom” current of Christianity that emerges in this book is not in contradistinction to creedal structure but can operate effectively within it. It is true she shifts the emphasis from being rescued (soteriology) to finding the Christian Wisdom path (sophiology), but she does not entirely discard the mainstream Augustinian trajectory either. She only points out that it has been overemphasized.

In The Wisdom Jesus, Bourgeault notes (as Robin Amis did long ago) that “gnosis” is a perfectly normative New Testament word. “Gnosticism (capital G),” she adds, “is the distortion that inevitably results when one tries to download gnosis (integral knowing) into exclusively mental constructs.” She goes on: “I find nothing in the Gospel of Thomas that contradicts any of Jesus’s teachings in the canonical gospels. Rather, it rounds them out metaphysically and creates a newfound sense of awe as we see just how original and subtle his understanding really is.”

Those who think Bourgeault is going to compromise on the necessity of the physical resurrection of Christ, without which, according to Paul, our hope is in vain, will be pleasantly surprised. She insists, “There are many skeptics who say that Jesus never rose. I myself believe that he did, and I stand my ground with the Christian tradition when I affirm that his resurrection does indeed make a profound difference to how we live our lives here and now.”

She insists, “There are many skeptics who say that Jesus never rose. I myself believe that he did, and I stand my ground with the Christian tradition.”

I do not love the Gurdjieffian and Sufi riffs that she adds after that passage, but any traditionalist trapper, on reading this, can still rejoice. Bourgeault weaves her alternative, but nevertheless genuine, Christian path from a variety of more recent sources, primarily Valentin Tomberg, Raimon Panikkar, Bruno Barnhart, Olivier Clément, Sebastian Brock, Thomas Merton, and others. The older quarries she mines to pave this Wisdom path are the Church of the East, Syriac liturgies, Celtic poetry, some Sufism, the Nag Hammadi (which she reads, as we’ve seen, through the canonical tradition), and especially the Lutheran mystic Jakob Böhme. The clasp that ties it all together, moreover, is not really the Gurdjieff work but the chanted Psalms and the rhythms of Benedictine monasticism. The especially scrupulous might call this uncommon blend of inspirations “heresy,” I suppose, were it not for the fact that it is all anchored in the Trinity, the ultimate “icon of self-emptying love.” It might be better to compare this “Wisdom Christianity” not to outright heretics but to pious Methodists, except that, while their “method” was personal holiness, Bourgeault’s is “surrender, attention, compassion.”

Most biblical commentators would say Bourgeault makes too much of the distinction between philia and agape in John 21. Agape, unlike philia, she says, is “nonattached and freely self-giving.” But I far prefer her shorthand equation a = ek (agape = eros × kenosis) to such exegetical peccadillos. Honestly, when someone writes this directly and insightfully about the spiritual life, who really cares if she is seminary-approved?

Our jagged and hard-edged earth plane is the realm in which this mercy is the most deeply, excruciatingly, and beautifully released. That’s our business down here. That’s what we’re here for.

Or this:

Our only truly essential human task here, Jesus teaches, is to grow beyond the survival instincts of the animal brain and egoic operating system into the kenotic joy and generosity of full human personhood.

The Centering of Centering Prayer

But Bourgeault does not leave us with mere abstract assertions, however elegantly she formulates them. If the Episcopalianism into which she was ordained left her wanting, she addresses it with what may be her best books, which survey the style of quiet Christian meditation known as Centering Prayer. Bourgeault does so much more in these books than popularize Centering Prayer. She establishes it, refines its nuances, and teases out the inherently Christian dimensions of this method, where thoughts are surrendered and a single prayer word facilitates the task.

In the first of these practical books, Centering Prayer and Inner Awakening, Bourgeault emphasizes that Thomas Merton, Thomas Keating, and John Main (effectively the modern movement’s three founders) “recognized meditation not as a newfangled innovation, let alone a grafting onto Christianity of an alien tradition, but rather, as something that had originally been at the very center of Christian practice and had become lost.” The twenty to thirty minutes of daily surrendering silence become, in Bourgeault’s hands, a form of deep Christian ressourcement.

Against the fashion for “non-duality” (a Christian borrowing from the Sanskrit term Advaita, “not-twoness”), Bourgeault insists that the “apparent duality of this world [is] not an illusion, but rather, a crucible in which the most tender and intimate particularity of the divine heart becomes fully manifest.” Centering Prayer is this crucible at highest heat. To pray this way is not to escape from reality but to enter into it, so much so that she once lightly chastised a group of Centering Prayer practitioners, lost in meditation, who neglected the simple task of answering a knock at the retreat centre door.

The scriptural grounding for this method comes from Christ’s self-emptying (kenosis) and our repentance (metanoia), a word that literally means to go beyond (meta) the mind (nous). Contemplation, moreover, is not an extra thing to be added to routine devotional life, as it sometimes appears to be in historical Christian sources. Bourgeault brilliantly recasts the classic contemplative framework by insisting contemplation “is neither infused nor acquired, because it was never absent—only unrecognized.”

In the second of these books, The Heart of Centering Prayer, Bourgeault doubles down on each of these insights. Centering Prayer is simply “kenosis in meditation form,” a practical application of Jesus’s teaching in the Gospels:

Let go! Don’t cling! Don’t hoard! Don’t assert your importance! Don’t fret. “Do not be afraid, little flock, it is your Father’s good pleasure to give you the kingdom!” (Luke 12:32). And it’s this same core gesture we practice in Centering Prayer: thought by thought by thought.

Most interestingly, Bourgeault heavily criticizes popular “mindfulness” research, such as Andrew Newberg’s How God Changes Your Brain, for its complete failure to grasp the Christian meditative tradition. When mindfulness researchers try to measure Centering Prayer, they eviscerate it of its Christian character, its “kenotic epicenter with its signature gesture of release” and that “mysterious golden tenderness . . . pure intimacy, without any cause.” Bourgeault thereby calls out the “Buddhist skew” of mindfulness research. For Christians, “mindfulness as attention is gradually transformed into mindfulness as participation in a living relational field, simultaneously intimate and cosmic.”

Bourgeault calls out the “Buddhist skew” of mindfulness research.

The One That Got Away

All of this might be enough to satisfy those in traditional circles who are suspicious of Bourgeault. But one of her books almost had me thinking otherwise. It is not that The Meaning of Mary Magdalene can be categorized with other proudly heretical books that—falling into the Gnostic Gospels trap—celebrates Mary as an apostle over against the other apostles based on spurious apocryphal texts. We’ve already seen how Bourgeault avoids all that by revering the canonical Gospels first and foremost. Instead, Mary Magdalene is for Bourgeault an illustration of “Wisdom Christianity” at work. Mary Magdalene “gets the message,” and all four canonical Gospels indeed testify to precisely that. When ministering to disaffected former Christians at the Nine Gates Mystery School, Bourgeault discovered that her discussion and application of Mary Magdalene’s vocation to anoint Jesus warmed such disaffected hearts to Christianity again.

So far, so good. But Bourgeault lost me in her reticence to argue that Jesus and Mary Magdalene did not physically consummate their relationship. “While it is tempting to speculate which version [celibate or non-celibate] Jesus and Mary Magdalene might have practiced,” Bourgeault insists, “in the end this turns out to be the wrong question. Either way that would have been fine.”

But that wasn’t the wrong question for her and Rafe, and Gurdjieff might have done well to ask it more rigorously. Indeed, to intimate that it may not entirely matter whether Jesus and Mary Magdalene were sexually involved offers a free pass to the sexual dalliances (if not outright abuse) perpetrated by Christians past, present, and future. Honestly, Bourgeault’s reticence here is so uncharacteristic that I wonder if it was the intervention of an editor hoping for Da Vinci Code–level sales. After all, in the same book, Bourgeault goes so far as to claim that the penitent-prostitute motif (pilloried by most Mary Magdalene scholars), however distorted, illustrates the “true bull’s eye of the Master’s teaching”—namely, surrendered, kenotic sexuality. I can only conclude, then, that if Bourgeault and Rafe could achieve a celibacy “purified of avarice and self-protectiveness,” then Jesus and Mary Magdalene would have done the same.

Moreover, the entire foundation on which Bourgeault built The Meaning of Mary Magdalene, the so-called Gospel of Mary Magdala, is shaky at best. For that is not even the actual title of this elusive apocryphal text, which some scholars have rashly attributed to Mary Magdalene. Instead, the Gospel of Mary, as Stephen Shoemaker contends, could just as well be about Mary of Nazareth. Unfortunately, Bourgeault relegates this Mary to a dismissive endnote, even while the Virgin Mary, most especially in her icons, illustrates the “slow and persistent overcoming of the ego through lifelong practice of surrender and nonattachment” that Bourgeault so instructively commends.

The thing about being a traditionalist trapper, you see, is that you must be willing to admit defeat. And The Meaning of Mary Magdalene, compounded with Bourgeault’s next book, Eye of the Heart, almost brought me to that. The latter, while not without luminous insights, contains Bourgeault’s most elaborate Gurdjieffian explications. Urgent appeals like “Pray to God, while there still is time” and “I believe evil is absolutely real” are interspersed with elaborate cosmological maps and words like “Trogoautoegocrat.” But the book’s entire premise is an unexpected sailing escapade with a man she calls “the Greek.” Just before one is tempted to criticize her for such foolishness, however, Bourgeault does so herself, quite severely. Like Thomas Merton’s confession that his affair with the mysterious “M” entailed “going against all that was true and authentic in my vocation, going against the grace and love of God,” Bourgeault regrets her liaison as well. Concluding that she violated her own rule of appropriate detachment, Bourgeault explicitly casts herself as Jonah resisting her calling. God, in short, sabotaged her Caribbean caper with the Greek. As she describes sailing mishaps and even life-risking scrapes, her tone is grave: “We escaped with our lives this time.” It is enough to wonder if she was keeping up with her commended practice of Centering Prayer on the sailboat. It is enough to wonder whether Bourgeault’s “Wisdom School” of Christianity is always entirely wise.

Bourgeault explicitly casts herself as Jonah resisting her calling.

Jonah’s Return

But I also wonder whether God interrupted her misadventure because Bourgeault had more necessary books to write. First came a book, Mystical Courage, that arose from the pandemic, in which she develops a more complete Christianization of Gurdjieff’s practical counsel with the help of a Maronite priest. She goes so far as to say, as many have long suspected, that “much of Gurdjieffian teaching is not only intrinsically mystical but also actively rooted in the Athonite tradition of Orthodox Christianity.” The next year Bourgeault went even further. In The Corner of Fourth and Nondual, any concerns that she has departed from classical Christianity are once more allayed. I will list her assertions in bullet points (as she does in this short book) for convenience:

- “Jesus is a real presence to me, not simply a ‘Christ consciousness,’ and the eucharist is the epicenter of this presence.”

- “Atonement is incontrovertibly real, and all attempts to sidestep or downsize it wind up in a bloodless Christianity and a cheapened and desacralized universe.”

- “I have never lost faith that there is such a thing as a unified Christian cosmovision that is vast enough to span the eons and tender enough to hold Jesus Christ at its epicenter.”

- “The highest levels of consciousness must necessarily be more personal, not less, for ‘higher’ by definition means ‘more relational’ and ‘more relational’ by definition means more personal. . . . [This] is the mystery at the heart of the Trinity, which now re-emerges as the quintessential mandala of the Christian nondual.”

- “We [those subscribing to Cynthia’s “Wisdom School”] steer clear of esotericism simply as mental or metaphysical speculation, and we affirm the primacy of the scripture and tradition as the cornerstone of Christian life.”

With this, my traditionalist trap sprang again, and I declared victory. Such a ringing endorsement of recognizable Christianity, which avoids head games and is grounded in reflective practice, would itself be a magnificent conclusion to an entire career. As an added bonus, unlike Rob Bell, Bourgeault counsels young seekers against the use of drugs to supplement the spiritual quest. Gratifying as all this might be for us traditionalists, nothing had quite prepared me for her newest book, out in 2024, which examines the work of the Centering Prayer popularizer Thomas Keating. The book offers a service that only Bourgeault could provide, and she provides it with magnanimity, flair, wit, and precision.

Many who have followed Keating’s career are quite aware of the theological slapdashery of his Centering Prayer workshops (freely available on YouTube), however interspersed they may be with scintillating insight. These slips, such as “Maybe [reincarnation] could be true” or (in an interview) “When you are God there is nothing to see,” are especially unfortunate because they are cherished jewels for many of Keating’s more “expansive” fans. As Keating embarked on what he called his “night job” at the Snowmass interfaith conference, and as he enjoyed appearances at the inter-spiritual Lama Foundation near Taos, many assumed that this prize contemplative—by appealing to world religions and non-duality—had moved beyond the presumably boring confines of Christianity.

Or so it was thought. What has long been needed is a skilled Christian teacher, deeply anchored in the Centering Prayer tradition, to interpret Keating correctly—not, mind you, to save appearances and make him seem more Christian than he was, but instead to report what actually happened at the end of his life. For this report to be convincing, this service could only be provided by a well-practiced contemplative who knew Keating intimately and was there at his death. And this is what Bourgeault has finally offered.

She manages this through some deft disentangling. As I have pointed out before, Bernadette Roberts is a deeply untrustworthy mystic, and many Christians who casually affirm her show no signs of having engaged her later books, which are especially disastrous. Bourgeault, however, charitably decouples Roberts from Keating. Whereas Roberts wanted to tear down the traditional Christian contemplative mansion, Bourgeault shows that Keating aimed instead to build on this mansion a spacious new wing.

As Bourgeault charts the twist and turns of Keating’s life, we can see that—like Merton and Bourgeault herself—Keating almost veered off the path. Owing to his inter-religious partners at Snowmass and Taos, Bourgeault admits that “for a while that wide-open freedom seemed to eclipse his loyalty to Christian theological models.” There was indeed a time when Keating nearly “attained escape velocity and blasted into celestial orbit.” Like the Indian monk Abhishiktananda, about whom I believe we should have serious reservations, Keating’s life almost ended there. “But,” Bourgeault adds, “Thomas’s old buddy God had other plans in mind.”

Because she was in the room where it happened, Bourgeault is able to report that “despite his earlier proclamation that ‘religious rituals and symbols . . . are meaningless to me now,’ Thomas returned faithfully to his old monastic breviary, reading and digesting the psalms as he had from his earlier year of monastic formation.” The passing Keating clung to Charles de Foucault’s classic Abandonment Prayer “like a long-lost friend.” “Father,” Keating asked his monastic brothers to pray over him, “I abandon myself into your hands; do with me what you will.” Faced with the assumption from her followers that Keating’s appeal to a heavenly Father amounted to an offensively trinitarian “regression,” Bourgeault stands her ground: “This was not a regression, only the return of a mode of relationship that had carried him all his life.”

Faced with the assumption from her followers that Keating’s appeal to a heavenly Father amounted to an offensively trinitarian “regression,” Bourgeault stands her ground.

With this revelation, the wavering Keating can be interpreted through his final return. Parsing his mature publications, Bourgeault shows him to be still firmly within trinitarian contours, the gaffs notwithstanding. All of Keating’s adventurousness is still there, all of his appropriate charitable regard of other faiths. But in Bourgeault’s hands he becomes, at last in print, what he truly was.

I believe that Thomas’s Christian orthodoxy was never seriously in question. Despite its increasingly untraditional language and “in your face” nondual koans, it still bears the essentials of Christianity in both form and substance; at its theological core it remains unshakably kenotic, subtly paschal and implicitly Trinitarian.

Upon reading those words, I recognized Bourgeault to be the “abler soul,” in the wonderful words of John Donne she cites so frequently. At last I saw that Bourgeault herself is a traditionalist trapper as skilled and intrepid as the French voyageurs of old, even if she (like Keating) resisted that vocation for a spell. For by artfully navigating multiple religious traditions, actual heretics, and the mists of non-dual teaching to show Keating himself to be a traditionalist, she bagged the biggest buck of all. If Keating’s “old buddy God” had other plans than to allow his Trappist son to leave the Christian fold, the same God, I am happy to report, also had other plans for that daring and dauntless theological trapeze artist, our Jonah to the New Age Ninevites, Cynthia Bourgeault.

True Wildness

Thrilling as the task has been, I might be done with my hobby of traditionalist trapping. Fascinating mystical writers like Merton, Keating, and Bourgeault may have strayed and returned, but their souls were scorched in the process; and they surely have influenced more than a few readers who, lacking similar training and formation, may fail to return themselves. I hope never to find myself in the place that Bourgeault did when her boat nearly sank in the Caribbean, nor do I hope to be “blasted into celestial orbit” as Keating nearly was after his interfaith trysts at Snowmass and Taos. No one should wish to arrive where Merton did near the end of his life, after his affair, writing in his journal:

I experience in myself a deep need of conversion and penance—a deep repentance, a real sense of having erred, gone wrong, got lost—and needing to get back on the right path. Needing to pray for forgiveness. Sense of revolt at my own foolishness and triviality. Shame and amazement at the way I have trifled with life and grace—how could I be so utterly stupid!

If—as authors like Bourgeault ultimately teach us—the real “wildness” is within the material world and not beyond it, and within the underestimated yet infinite horizons of classical Christianity, then the most adventurous path of all may be to believe traditional doctrines, to stay faithful to one’s respective vows, to recite the creed and receive the Eucharist weekly, and yes, to cultivate habitual surrender by engaging in daily bouts of silent contemplative prayer.

That would be a faith so wild that it has the courage to appear tame.