I

I have no evangelical trauma story. While I am genuinely sorry for those who do have trauma stories, I come up short when scanning my own experience in evangelicalism for cults of personality, charismatic grifters, or spiritual abuse. I am keenly aware such things happen, because the algorithms that deliberately amplify such occasions won’t let them escape anyone’s notice. But my lived reality of “evangelicalism” (I’ll explain what I mean by this below) was in practice not flashy unfaithfulness but unflashy faithfulness. This is not the stuff from which bestsellers are wrought. I’m not expecting a huge follower boost on social media for my big tell-all announcement that evangelicalism pretty much worked, and—when appended to robust ecclesial structures—still does.

In a word, evangelicalism was God’s instrument to rescue me. I do not remember my youth pastor pushing “purity culture,” but he did kindly warn us, as the New Testament does, to avoid sexual immorality. When some of us asked him what marriage was like, he told us, “You have to learn to love more.” Any among us who might have thought our youth pastor was about to extol the glories of marital intimacy would have been disappointed to learn he was talking about doing the dishes.

This was back in the 1990s, the decade that Christian Smith says, in his recent book Why Religion Went Obsolete, marked the twilight of serious religion. Back then “postmodernist and social constructionist ideas fostered skepticism toward absolute truths, especially among younger generations, while multicultural education inadvertently promoted cultural relativism, making strong religious adherence less plausible.”

But evangelicalism was a preservative from all this. Another pressure that Smith says was squeezing religion at that time was careerism’s all-consuming demands. “Your dream job is out there . . . so never stop hustling,” my generation was told. Smith reports that this was “a blueprint for spiritual and physical exhaustion.” But evangelicalism taught me the gospel, so I received spiritual refreshment instead. The careerist treadmill just whirled on without me.

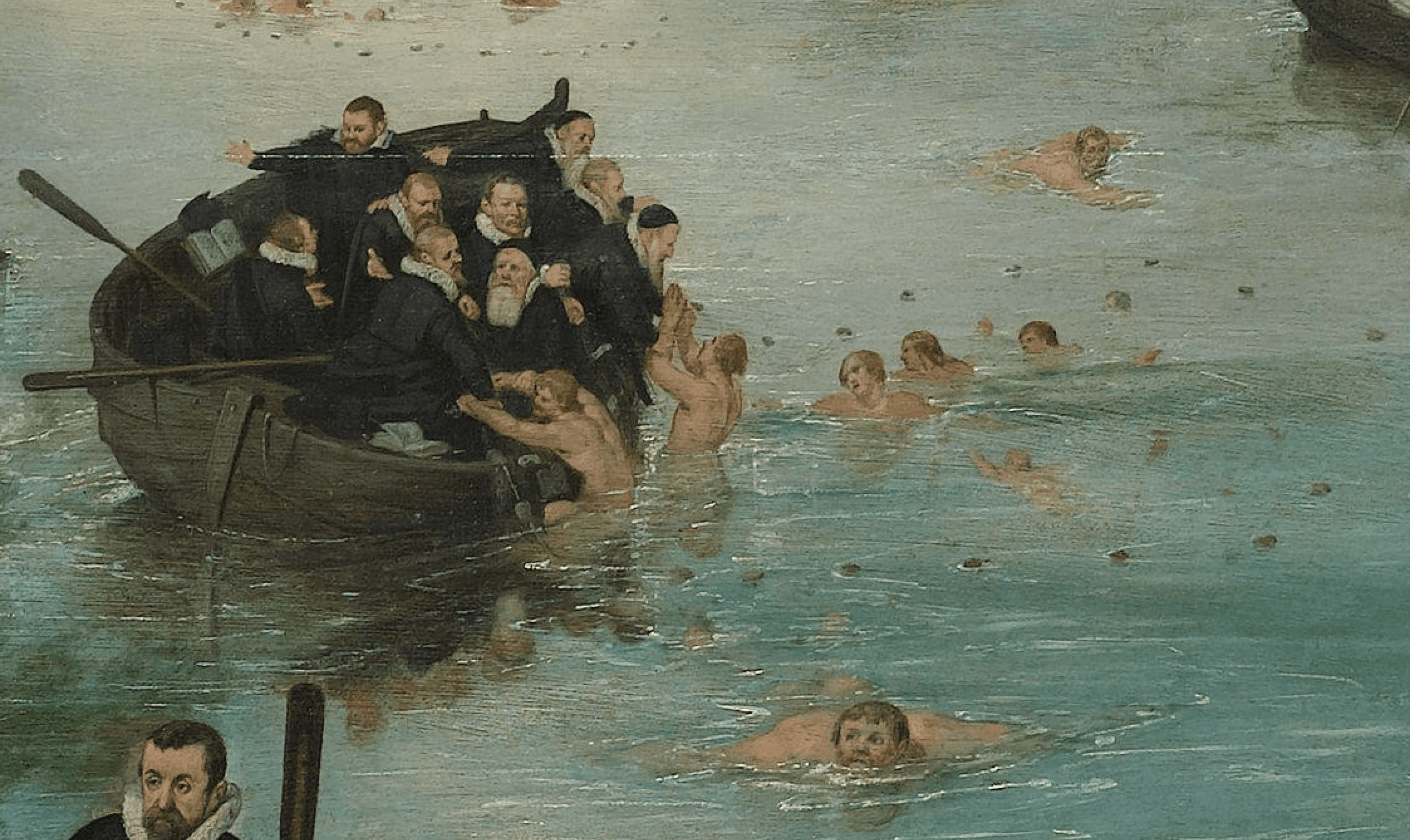

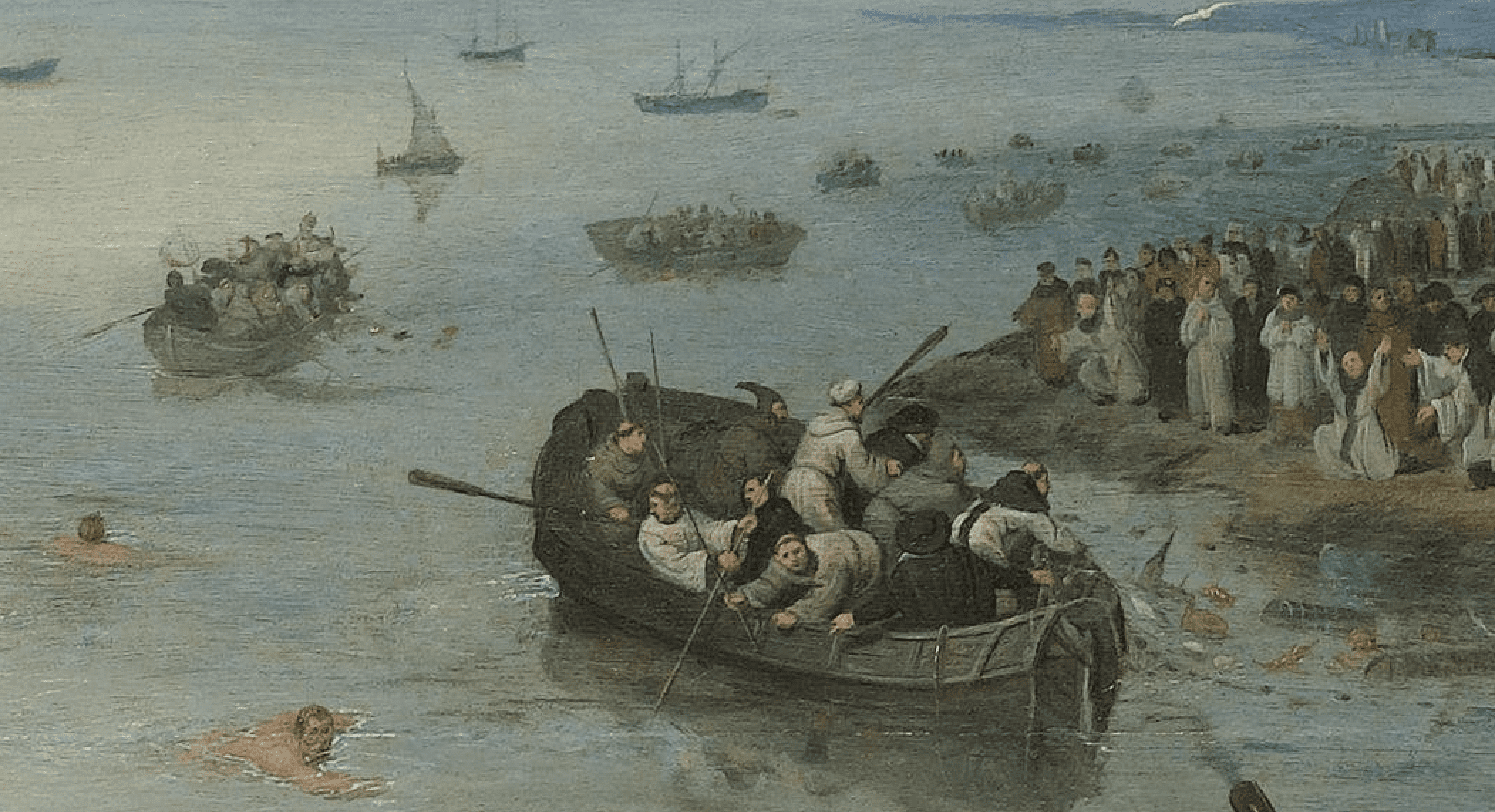

Adriaen van de Venne, Fishing for Souls (detail).

For me, “evangelicalism” comprised ordinary Christians appended to the youth group of a local Methodist church. Our morning “breakfast clubs” included praise and worship, cheap powder donuts, and short Bible studies offering emergency relief from the blood sport of the high school cafeteria. Our “lock-ins” offered not gimmicky entertainment but serious events of spiritual renewal where I learned the high stakes of sin and salvation and was told I had to respond. I remember a woman in her fifties organizing a weekend of renewing prayer for the congregation to which the youth group was also invited. The light in her eyes told me that she was more alive than most of the adults I knew, and I wanted that life for myself. Amazingly, if I would just receive the gospel, that new life was there for the taking.

I call this youth group “evangelical” because it perfectly fits the definition of evangelicalism known as the Larsen Pentagon: (1) orthodox Protestantism, in (2) a tradition stretching back to John Wesley and George Whitefield, with (3) a preeminent place for the Bible, while (4) stressing reconciliation with God through Christ’s atoning work, and (5) the work of the Holy Spirit in conversion, service, and proclamation. I love my country and wish it well, but this pentagon is far more cosmically significant than anything that goes on in the Pentagon in Arlington, Virginia. Still, evangelicalism wasn’t a series of five theological bullet points dictated to us as much as it was a lived reality connected to a local congregation. Each of these principles was enfleshed in mature, average Christian adults who took the time to volunteer.

One of these volunteer leaders infused evangelicalism with a mystical element. She was a judicial clerk at the New Jersey Superior Court. Many of us were drawn to the depth of her faith. We knew she prayed for us. She introduced us to Thomas Kelly’s classic Quaker book, A Testament of Devotion (1941). She gave me a hardcover copy that I still own. As kids, after jumping over the Speedline turnstile, we used to steal into Chinatown to buy fireworks. Reading that book set my heart ablaze like a jumping jack or a Roman candle. The great mystical treatises penned in the Catholic Middle Ages and the secret wisdom embedded in the Orthodox Philokalia are in perfect step with Kelly’s cri de cœur:

Let us explore together the secret of a deeper devotion, a more subterranean sanctuary of the soul, where the Light Within never fades, but burns, a perpetual Flame, where the wells of living water of divine revelation rise up continuously, day by day and hour by hour, steady and transfiguring.

Evangelicalism was not a political program or an apologetic battle strategy but a gateway into the presence of God, one that can lead in time to responsible politics and appropriate apologetics. As Kelly puts it, “Life from the Center is a life of unhurried peace and power. It is simple. It is serene. It is amazing. It is triumphant. It is radiant. It takes no time, but it occupies all our time. . . . We need not get frantic. He is at the helm. And when our little day is done we lie down quietly and in peace, for all is well.”

Now that I know the history of the Quakers in the New Jersey area, and their success in missions among the Leni Lenape, my introduction to Quaker mysticism through evangelicalism is especially appropriate. The claim that my experience was reducibly “white” is therefore somewhat silly. As I wrote in The Everlasting People, evangelicalism, infused by Quakerism, was originally successful among Native Americans in the same area hundreds of years before—until, that is, the tide of settlers tragically pushed them out. But it was evangelicals who protected the Native Americans (many of whom were also evangelicals) from the voracious interests of settlers.

It was evangelicals who protected the Native Americans (many of whom were also evangelicals) from the voracious interests of settlers.

My being engrafted into the evangelical movement was therefore an escape from merely affluent “whiteness” (how I dislike that unhelpful term) into the multi-ethnic body of Christ. Only thanks to evangelicalism was I throttled into communities beyond my own suburban enclave, as our youth group partnered with other ministries in nearby Camden and Philadelphia. “Christ is with the poor,” one Camden minister told me, with a slight warning in his voice lest I forget. Were it not for evangelicalism, I would never have heard those words.

Yes, there were the dispensationalist charts (enthusiastically unfurled by one volunteer leader), but her love and devotion to Christ, and to us, easily outstripped any overly precise end-time predictions. Yes, I picked up some bizarre conspiracy-theory tracts at the Christian bookstore, which warned of an impending New World Order run by the Illuminati; but when I approached others in our youth group with all this, they just wisely directed me back to the Bible. Yes, there was contemporary Christian music and the looming corruptions of “Cashville” (one nickname for Nashville, Tennessee), but all I received from those tapes and CDs was a necessary catechism for my adolescent emotions. When I was lucky enough to once meet the Christian music star Rich Mullins, he was about as disarming a person as I could have imagined. When I showed awe at his talent, he invited me to breakfast with the band so I could see he was a flawed mortal human like everybody else.

The script tells me that I’m now supposed to relate how it all broke down and was hopelessly compromised. But decades later, the unflashy faithfulness hasn’t quit. I recently had a chance to visit my old youth pastor and his wife when I spoke at a conference he put together for the Presbyterian church he now leads. His house was, as it was when I was in high school, something of a hostel. I was there with a young couple who were visiting from South Africa, a respite from their work on the front lines of prison ministry. Before I left, another couple, processing a painful church split, came to stay. We sipped some South African wine and shared stories about God’s dramatic faithfulness in our work over the years, from the days of youth group to the present. As we conversed, I realized each of us had supplemented the evangelical faith that drew us into the church with resources drawn from the wider Christian tradition, but without giving up on the hallmarks of evangelicalism.

In our conversations after the conference, my old youth pastor told me—commenting on the way I answered questions—that I still think like an evangelical. He’s probably right. Admittedly, I worship in an Anglican church, which includes the sacraments of course, not to mention the episcopacy—features Anglicanism shares with Orthodoxy, Catholicism, and some branches of Lutheranism. Part of the reason I don’t worry about evangelicalism, therefore, is that for me it is ensconced in this wider ecclesial framework. Thomas Kelly alone would not have sufficed for the long haul any more than Catholic or Orthodox mysticism would apart from liturgy and the sacraments. As Evelyn Underhill said of Quakerism, the Inner Light “burns with a better and truer flame” when it submits “to the limitations of the lamp.”

This structural stability means that many spiritual trends and hot topics of “Big Evangelicalism” are lost on me. I don’t need to “deconstruct” my faith because I have read Dionysius the Areopagite, who does such a better job of that than modern Christians, all the while pointing me to the un-deconstructible mystery of Christ. I don’t wring my hands about the latest trinitarian controversies that enervate the “evangelical conversation,” because I have read about when they arose (and were in some respects resolved) many centuries ago. My subjective emotions are assuaged with the sacraments, which point to the objective work of Christ, and my anxieties about God’s will for my life are replaced with the responsible freedom that grace engenders.

I don’t need to “deconstruct” my faith because I have read Dionysius the Areopagite, who does such a better job of that than modern Christians, all the while pointing me to the un-deconstructible mystery of Christ.

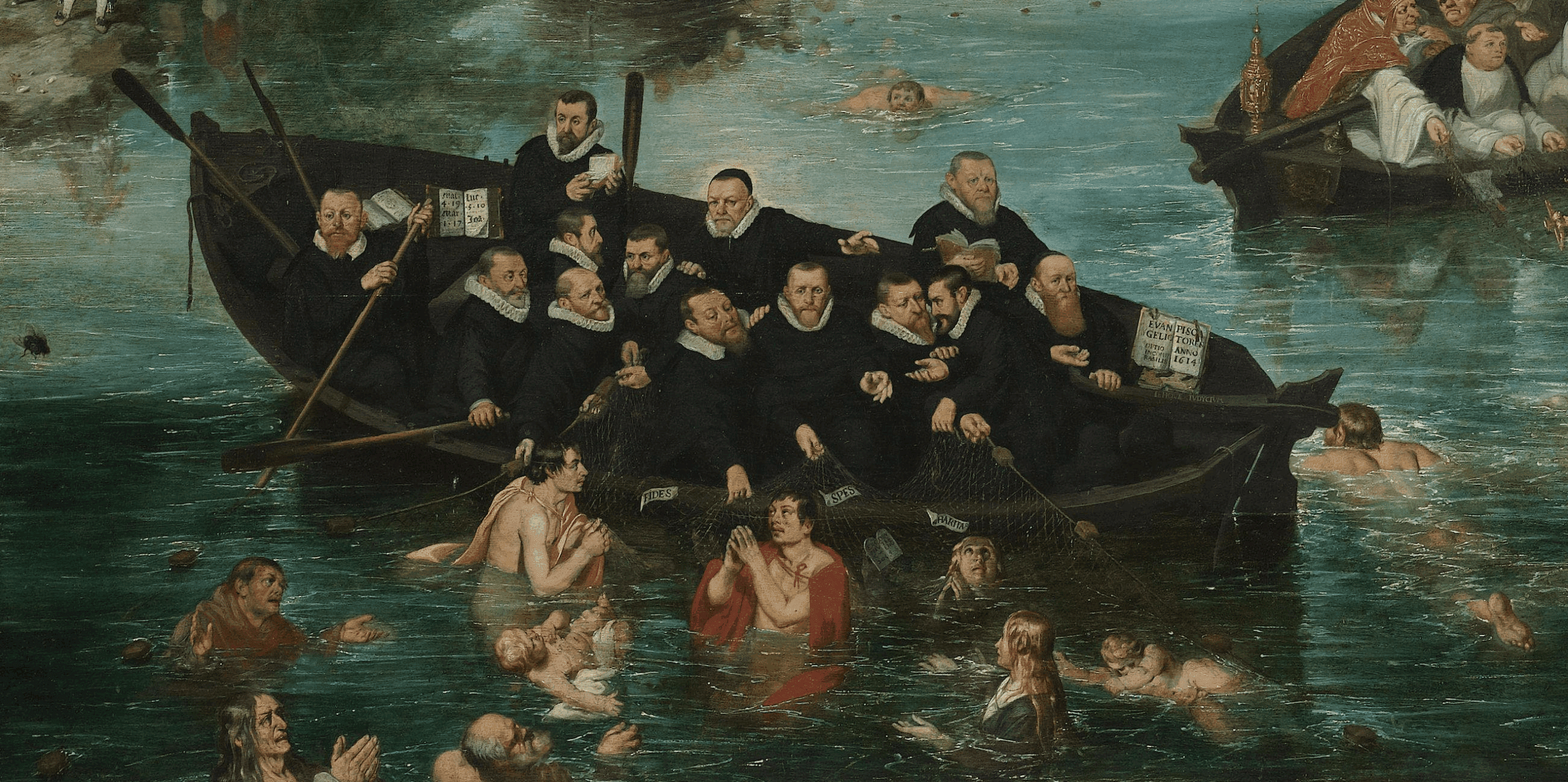

Adriaen van de Venne, Fishing for Souls (detail).

Visiting my hometown recently for the first time in decades, I stopped by that Methodist church where I came to Christ. It was not a warehouse with a neon sign labelled “EVANGELICALISM,” but a beautiful neo-classical building whose bare elegance influenced my teenaged mind unconsciously but powerfully. A staff meeting was going on, so I let myself in and toured the structure, probably violating some kind of state or church safety laws. There was the hallway where I first saw what a lively faith looked like in an adult. There was the sanctuary where I first heard the strange words of the Psalms. (What, I then wondered, is a “psalm”?) There was the old youth room, still on the top floor of the church and still equipped with tattered couches (I hope not the same ones), where I first heard strange words like “Exodus” and “Deuteronomy” and where the gospel first became real. When the staff finally caught on to the fact that a strange man was wandering their building, one of them asked if they could offer assistance. I told them, a bit choked up, that I came to Christ in this building thirty or so years ago and to please keep up the good work.

If I have disappointed the reader by not relating how evangelicalism is in fact rotten to the core, I must now compound the disappointment by explaining that I am not now going to upgrade my religious experience by “converting” to Catholicism or Orthodoxy. I visited the Catholic Church as well in my old hometown, where my parents had dropped me off for Sunday school. Its name is Christ the King, and I will be offering no cartoonish critique about how Catholics offered royal triumphalism and only evangelicalism offered the suffering servanthood of Christ. Not in the least. This church’s beautiful stained-glass interior clearly displayed, both then and now, how the kingship of Jesus flows only from wounded hands. I do wish, though, that someone in that church, where I was processed through the Confirmation rite with exceedingly minimal preparation, had explained that to me.

I have already explained the forgivable failures of this parish, and I do wish it had been more effective in its ministry. Thankfully, the Holy Spirit made up Catholicism’s pastoral deficit by employing another wing of the same Nicene faith—one animated by evangelicalism—to more securely graft my teenaged self into the one mystical body of Christ. “There is one body and one Spirit, just as you were called to one hope when you were called, one Lord, one faith, one baptism” (Ephesians 4:4). Such singularity meant that when I asked my youth pastor if he would baptize me at the Jersey shore, he—knowing I had already been baptized in Roman Catholicism as an infant—wisely refused.

Entering the darkened interior of Christ the King Catholic Church, I knelt to pray before statues of the Virgin Mary and Joseph; I rejoiced before Christ’s real presence in the sacrament. Neither of those elements are present in the Methodist church I came to Christ in, and indeed, if you were to force me to choose, I would say that the saints and the Eucharist are such an indispensable element of my faith now that I would choose Catholicism over Methodism. But thankfully this is only a paper dilemma, because I belong to an Anglican congregation where I now live, one where both the evangelical element and the Eucharist, the saints, and the Virgin are all properly celebrated.

As to why I don’t leave all this for the splendour of Eastern Orthodoxy, I can reply that I did pursue a PhD in the subject, enabling my understanding of Orthodoxy to be shaped by the mother countries of Greece and Cyprus, not only by American refractions. When I learned from Orthodoxy, contrary to twisted punitive atonement theologies, that there is no conflict in the life of the Trinity, it all sounded vaguely familiar. This was because I had read the same thing long ago thanks to evangelicalism—namely, in John Stott’s classic book The Cross of Christ: “God does not love us because Christ died for us; Christ died for us because God loved us.” Once at a clifftop monastery in Meteora, I read a placard emblazoned with the words from John Chrysostom’s famous Easter sermon: “Sober and slothful, celebrate the day! You that have kept the fast, and you that have not, rejoice today for the Table is richly laden!” Thanks to evangelicalism, this message of unmerited grace was no discovery for me, but a joyous remembrance.

Again, if I had to choose between a Christianity with the Virgin Mary and a Christianity without her, I would quickly choose the former; but this is a false dichotomy, for there is no true Christianity without the Virgin. I love that John Geometres in the Orthodox tradition boldly asks, “How could it be possible for such a song to praise her worthily . . . one who alone is daughter, mother, and bride of the One who exists?” But the exact same question was posed by my own Anglican tradition independently by John Donne: “What honour can unto that Queen be done / Who had your God for father, spouse, and son?”

Adriaen van de Venne, Fishing for Souls (detail).

There was, I confess, a time when I nearly did return to Catholicism, in which I was baptized and confirmed, and I have lovingly marked copies of John Henry Newman’s books to show for it. I once found Newman’s arguments nearly irresistible. Now when I read his claim that, because they did not submit to the papacy, “the first breath of persecution” made Coptic and Assyrian Christianity “crumble and disappear,” I think of the heroic martyrdom of Coptic Christians on the beaches of Libya, or the astonishing global witness of the Church of the East that has only lately come to wider attention. I still love reading Newman, but David Bentley Hart is right to suggest that so much of Newman’s argument “depends upon a stringently selective and ideologically determined reconstruction of the past, and upon the historian’s willingness to conceal countless other traditions as well.”

The Protestant tradition once felt uniquely unstable to me because of attempts by modern theologians to revise classical doctrines and ethics, thereby further distancing Protestantism from the mainstream theological tradition. I am glad these metaphysical makeovers to conform to whatever counts as “modernity” (or postmodernity, or metamodernity) are dissipating. Thankfully, leading lights are now reviving classical theology in a Protestant framework, showing me how the magisterial Reformation is very much part of the wider ecclesial flotilla, not an isolated and quickly sinking revisionist rowboat.

In retrospect, it is no wonder that I was so drawn to Catholicism and Orthodoxy as the only ways forward. I would read Thomas Aquinas or Gregory Palamas, and then read that Protestant revisionist theology, which was busy revising human sexuality as well. Such comparisons perfectly confirmed the suspicions that Catholics had about Protestantism in the debates of the Reformation, and the modern TikTok rhetoric of the Ortho-bros. But just as good Catholic and Orthodox Christians should rightly reject the revisionist theology in their own ranks, I reject Protestant revisionism. Now that I read Aquinas alongside Richard Hooker, Lancelot Andrewes, William Law, or John Keble, the contest has evened out. Now that I read Gregory Palamas alongside the countless books, chapters, and articles detailing the place of deification in classical Protestant authors, I see the grass is greening on my side of the fence as well.

None of this is to occlude the unavoidable matter of justification, so central to Reformation debates. It does not seem to me that trust in the full efficacy of Christ’s saving work on the cross is best described as “vain confidence of Heretics,” as the Council of Trent decreed. Justification is instead a bedrock of assurance against the punishing waves of a tumultuous psychic sea. The element of sanctification—progress in holiness—is also present in Protestantism, but this element is rightfully secondary and should not be confused with the full and complete work of Christ in justification. This is the classic Protestant distinction between righteousness coram deo (before God), a passive righteousness that is justification, and righteousness coram mundo (before the world), an active righteousness that is sanctification. The New Testament contains both elements; the first is complete, and the second is ongoing.

Accordingly, the very same biblical book can speak indicatively, announcing salvation is “not the result of works” (Ephesians 2:9), and imperatively, insisting we indeed “must work” (Ephesians 4:28). The Bible is not confused. Instead, the first instance regards the finished work of justification, and the second the continuing work of sanctification. We need not choose between them, even if we prioritize the former. No wonder Luther himself, against his modern caricatures, could insist that “faith without works . . . is false faith and does not justify.” It is not that Thomas Aquinas’s famous point of faith being formed by love (fides caritate formata) is wrong; it is instead that “the Protestants among us simply wish to point out that it is the fides (more precisely, God’s presence in the fides) rather that the formata that justifies.”

These two forms of righteousness—one finished (Philippians 3:9) and one unfinished (Philippians 3:12)—lead to a realistic view of ourselves and everybody else. Luther’s famous doctrine that we are at the same time just and sinful (simul iustus et peccator) is not a relic of obscure Reformation debates but a psychological fact. Honest consultation of one’s own life or study of Christianity’s many storied saints—who are ever conscious of their sinfulness—bears this out. As Jordan Cooper puts it, “While before God, we are declared to be fully sinners under the law and fully righteous in the gospel, before the world we are also partially saint and partially sinner.” Triumphalist strains of Protestantism that claim we can attain sinlessness in this life are a boulevard to burnout. But this does not mean we should cease from striving. We undergo spiritual discipline not to make God love us but because he already so very much does.

Luther’s famous doctrine that we are at the same time just and sinful (simul iustus et peccator) is not a relic of obscure Reformation debates but a psychological fact.

Similarly, as Protestants have indefatigably insisted, we perform good works less for God than for our neighbour. When Luther calls us to “sin boldly,” he is not saying we should deliberately sin but keeping us from scrupulous paralysis. As Ted Peters explains, Luther is simply acknowledging the “impossibility of pure moral action devoid of self-interest and . . . that moral action frequently takes place within a contextual situation where non-action is morally problematic.” As to the end of life, the Bible also speaks of our reward, but none of this can be understood apart from the gift of mystical union. The Anglican theologian Andrew Davison felicitously reports on Augustine’s insight, enshrined in the All Saints Day liturgy, that God, in crowning our merits, crowns his own gifts (eorum coronando merita tua dona coronas).

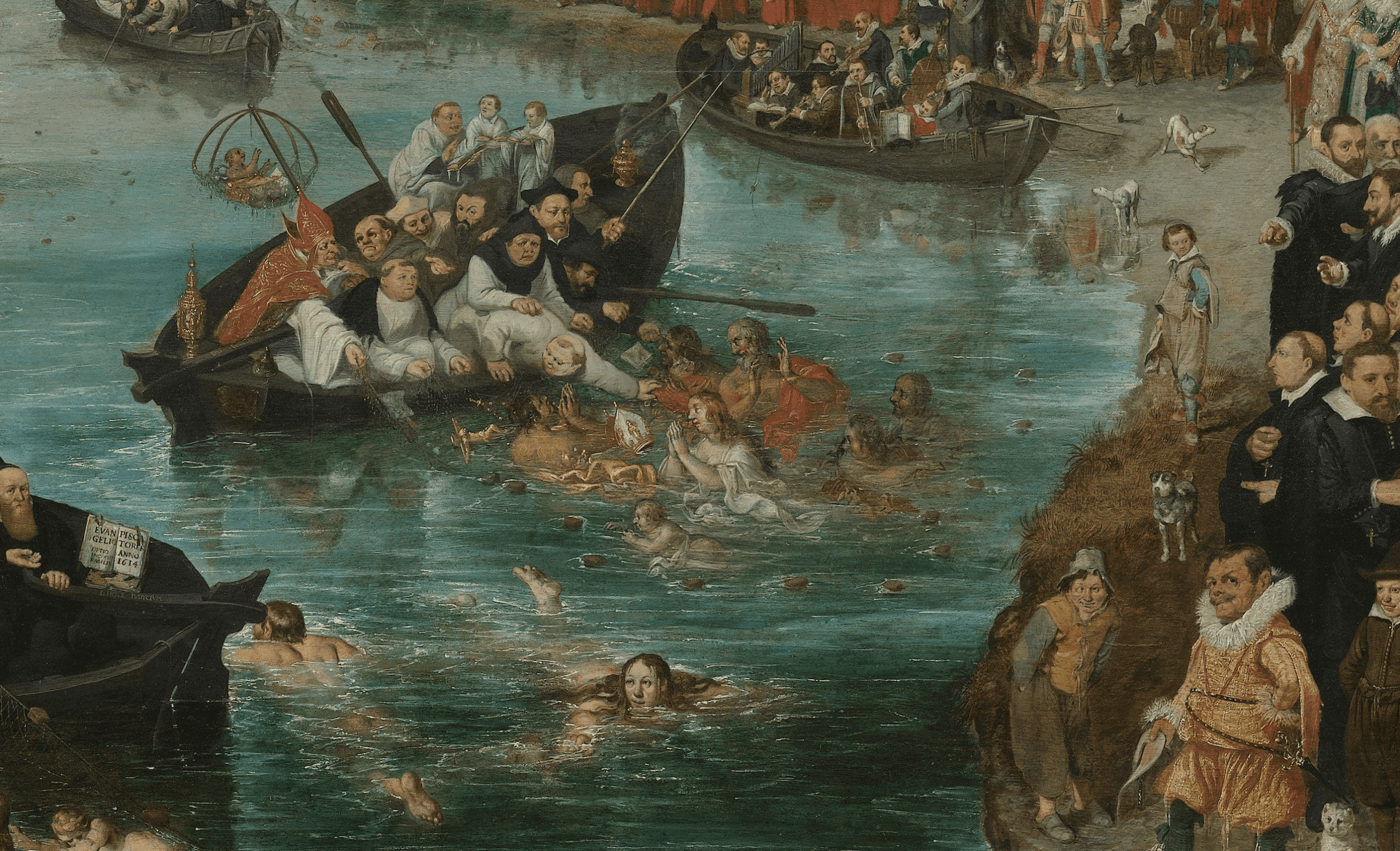

Adriaen van de Venne, Fishing for Souls (detail).

In sum, the priority of grace on offer in the classic Protestant position is not a point of historical curiosity no longer applicable to twenty-first-century people. On the contrary, this impulse is the very thing that brought me to Christ in the first place, and that keeps me coming back. As David Zahl puts it, upending Christian Smith’s recent thesis about religion’s decline, “Wherever the church embraces its role as a dispensary of grace, delivering the goods week after week after week, life abounds. Communities that keep their focus vertical—that is, on the God who dispenses relief—invariably flourish.”

Nor is the priority of grace a jealous possession of Protestantism. Wherever I see renewal in the Catholic or Orthodox traditions, it is often because of the recovery of those elements of unmerited grace, and for this I rejoice. “God’s love is absolutely free: we don’t have to merit it or win it, we only have to receive and welcome it,” writes the Roman Catholic priest Jacques Philippe, adding, “This is the only path to salvation, according to St. Paul.” It is no different in Orthodox circles. I will never tire of pointing students to the fifth-century treatise by Mark the Monk offering not 95 but 226 theses to those who think they are made righteous by works. “‘Evangelical’ is a perfectly good word for the quality of life, beliefs, and conduct of the early Christians,” insists the Orthodox writer Theodore Stylianopoulos. “Any aspect of Christian life and theology with essential connection to the Gospel may be called evangelical.” Still, with both Phillip Cary and Beth Felker Jones, I wonder whether these evangelical dimensions would be so perennial in the modern world and in other traditions were it not for their recovery and enshrinement by Protestants.

For those who find that last claim unconvincing, here is a story to consider. I have several times been among groups of Protestants invited to attend symposia at Mundelein Seminary, the flagship Catholic Seminary in the Chicago area. On one such occasion, we investigated medieval Catholic understandings of the doctrine of grace that were more in line with the Reformation (understandings that, arguably, were proscribed by the Council of Trent). On this occasion, I witnessed a remarkable moment. Just before the case could be made that the Catholic Church had always promulgated a robust Pauline sense of grace, the great scholar of mysticism Bernard McGinn interrupted the discussion and announced (and I quote from memory), “But by the sixteenth century, this understanding of grace had been buried!” Forgive me if I imagine the author of the biography of the Summa theologiae might know what he is talking about. And the Catholic defenders of John Henry Newman who concede “he most probably never read Luther firsthand” might know what they’re talking about as well.

Even so, people tell me that evangelicalism is politically compromised today. But I am not going to discredit the movement for this any more than I would condemn all of Orthodoxy because of the monstrous war being waged under its name by its majority Russian leadership. A monk from Moscow once told me in person that anything Putin did he would bless. I refuse to condemn that monk’s entire tradition because of this ill-considered remark. Nor would I dismiss all of Catholicism because of the sex-abuse scandals that have caused such incalculable pain. Because I believe Christians are justified while remaining sinful, I cannot pretend that those unsavoury factors of both those communions don’t exist; and the same of course goes for evangelicalism, and for my own Anglican tradition, which is fraught with lamentable scandal as well. As one of William Laud’s collects puts it, “We pray for your holy Catholic Church”—that is, for all of it. “Where it is corrupt, purify it; where it is in error, direct it; where in anything it is amiss, reform it.” The appropriately penitential Great Litany phrases it succinctly enough, no fewer than ten times lest we miss the urgency: “Good Lord, deliver us.”

The word “evangel” simply means the gospel, the good news, and the Christian use of the word undermines a political word originally meant to announce the supposedly good news of the arrival of Caesar. But I worship the true emperor, whose name is Christ. Evangelicalism brought me into the church, and thanks be to God it will continue to do that for many more. But no fish should be satisfied with the net and should instead wriggle up its fragile filaments to the ecclesial boat as fast as its scales will take it. On that boat, there are great benefits: the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, apostolic succession, a rich relationship with the saints, a lively love of the Virgin Mary. Because I enjoy all these dimensions within Anglicanism, a critique of evangelicalism that announces such deficits is, to me at least, so much banging on an open door.

No fish should be satisfied with the net and should instead wriggle up its fragile filaments to the ecclesial boat as fast as its scales will take it.

There is, I am all too aware, an evangelicalism that is untethered to the church. This kind of evangelicalism is more of a market. It thrived on the radio and television, and now it thrives on social media. There are good things in parts of this untethered movement, but my counsel to my evangelical students is to get themselves into the ship of the church right quick. It doesn’t matter how “powerful” a travelling worship concert “experience” was, how “impactful” (can we abolish that word?) their summer service project was, how “radical” the latest evangelical celebrity pastor’s book may seem. It’s a standard rule in fishing that if you don’t “boat” a fish, if you just hook it, you haven’t really caught it, and so it is with all of us influenced by evangelicalism. If all we have is a net, we will just fall back into the sea.

Adriaen van de Venne, Fishing for Souls (detail).

Still, the debt I owe to the net of evangelicalism is considerable. I cannot rewrite my own story, nor do I wish to. Kelly describes the mystery of Christian fellowship in this way:

Every period of profound re-discovery of God’s joyous immediacy is a period of emergence of this amazing group inter-knittedness of God-enthralled men and women who know one another in Him. It appeared in vivid form among the early Friends. The early days of the Evangelical movement showed the same bondedness in love.

So it was in New Jersey at the end of the last century as well. But in time evangelicalism expanded into a fellowship across the ages: “Time telescopes and vanishes, centuries and creeds are overleaped.” Kelly cites Augustine, Thomas à Kempis, Eckhart, and Brother Lawrence. He writes of “the Fellowship of the Transfigured Face” as if he were rapt before an Orthodox iconostasis. “It is as if every soul had a final base, and that final base of every soul is one single Holy Ground, shared by all. . . . Holy Fellowship, freely tolerant of . . . important yet more superficial clarifications, lives in the Center and rejoices in the unity of His love.”

In the transforming light of union, the dizzying differences between Christian confessions both matter and are transcended. It is in this mystery of deification where all my hopes for future confessional alignments across divided traditions lie. The answer was there all along in the faux-leather teenage-edition Life Application Study Bible that I read only because of evangelicalism: “The glory that you have given me I have given to them, that they may be one even as we are one, I in them and you in me, that they may become perfectly one, so that the world may know” (John 17:22–23). Curiously enough, the journey therefore began at the summit.

“It is not too late to love Him utterly,” urges the Quaker. I have not loved Christ utterly, but I know I have been utterly loved, which makes me want to love Christ utterly, but only Christ can offer such utter love. Pushed beyond myself, only the pearl remains—the pearl of union. The way of evangelicalism, for which I remain grateful and which must remain open, is eclipsed by the destination. Augustine surmised that because the members of Christ are in fact Christ’s own body, their love for one another means that in the end “there shall be one Christ, loving Himself.” And every moment is already somehow the end.