N

Not being myself from India, I could not be content with other people’s Marys. This Advent(ure) therefore had to continue. I needed to find my own Mary, from my own land. The Midwest Marys I had already explored have a source, and I wanted to find it. Seeing that this year was the 350th anniversary of Father Jacques Marquette’s famous journey into what he knew as the Upper Country (Pays d’en Haut), I decided to trace his journey. I visited the place in Wisconsin where he first saw the Mississippi River, which he named, in honour of the Virgin, the River of the Immaculate Conception. As I and some fellow Anglicans from my church looked over the Mississippi bluffs near the site, we wrestled with whether we could accept this title, which of course refers to a Marian doctrine—her being conceived without sin from the moment of her conception—that Roman Catholics have deemed mandatory, while the rest of the world’s Christians have not.

The river, it turns out, resolved this theological dilemma for us. One in our number mentioned visiting the headwaters of the Mississippi at the undistinguished town of Bemidji, Minnesota. “How astonishing,” he casually remarked, “that something so massive came from something so small.” It was a perfect encapsulation of how divinity emerged from the humble Virgin’s womb. There was no need to angrily dispute the Catholic doctrine. By shifting toward the doctrine of the virgin birth that all Christians share, my fellow parishioners and I found our answer to Marquette’s fluvial proclamation; and as we began to recite on the bluff that Sunday morning, the eagles flew below us.

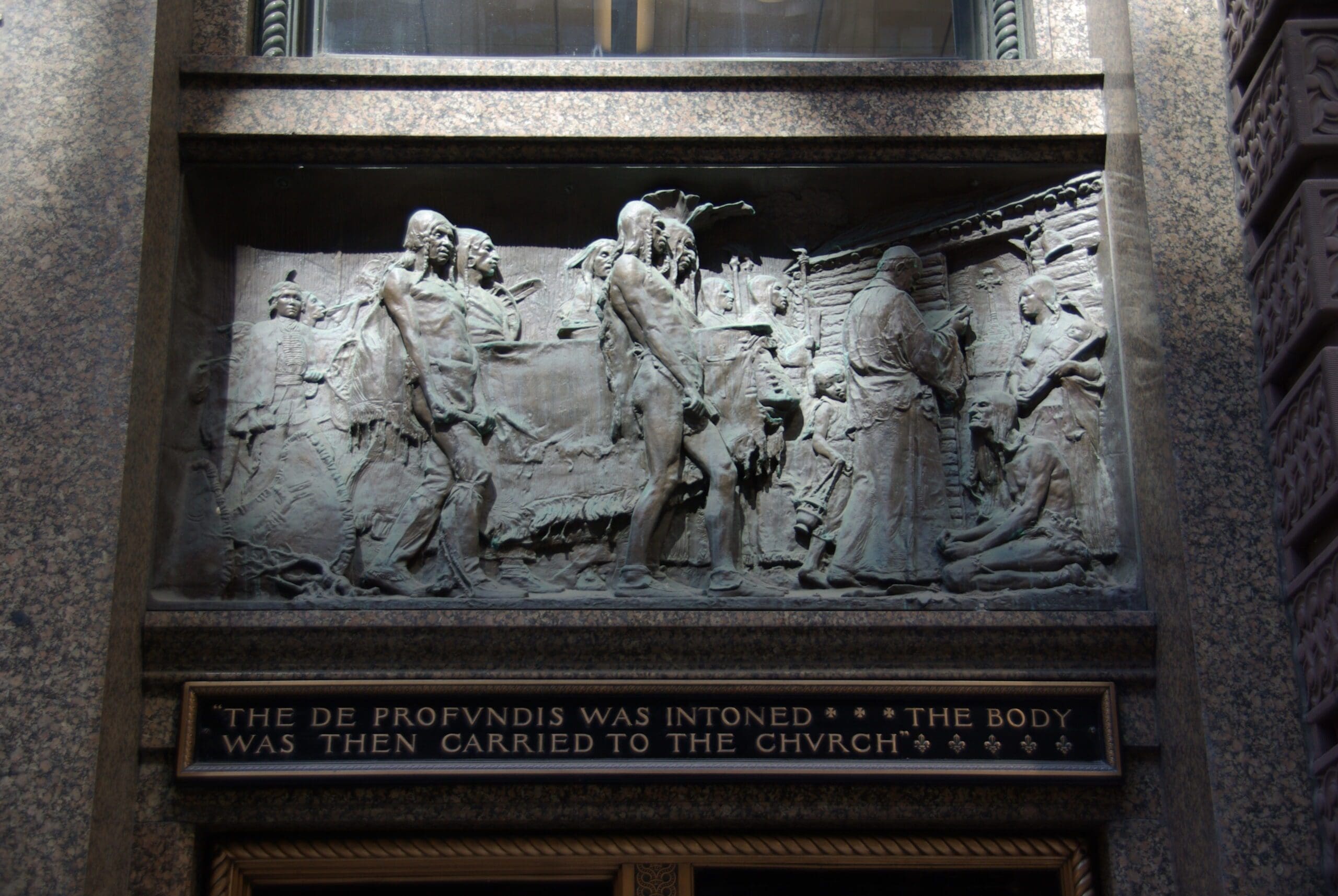

But Marquette’s journey was much longer than this stretch of the Mississippi, and so mine had to be as well. As my long-suffering family piled into the car, our Marian quest began. We first made our way to the magnificently modern St. Francis de Sales Church designed by Marcel Breuer, a surprisingly delicate concrete wave. As my wife and I disputed the church’s aesthetic merits (brutalism is not her style, nor is it entirely mine), we travelled to the place of Marquette’s death in Ludington, Michigan. “The De Profundis was intoned, the body was carried to the church,” reads the inscription on the Marquette building in Chicago, with a Native Virgin Mary in the corner, memorializing this solemn event. There is a large cross at the site of Marquette’s death in Michigan, now surrounded by a few American dream homes. We pressed on to where his body was buried at St. Ignace (named after Ignatius of Loyola) in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. When we finally arrived after crossing the Straits of Mackinac, once the trade fulcrum of North America, we were thrilled to discover that Marquette’s body—which had gone missing for some time—was actually there. It was returned in 2022. Native Americans and settlers presided together at the reburial ceremony. The Museum of Ojibwa Culture at the site, which displayed Marquette’s eucharistic chalice, proudly described the enduring compatibility of Indigenous culture and Christian faith.

Still, we aimed to go deeper, into the lands from which Marquette departed, hunting for the Mary that inspired him. First we visited Montreal’s many Marys, the most conspicuous of which was the Chapel of Notre-Dame-de-Bon-Secours. Here is where sailors would make their offerings of thanks for “good help” (bon secours) on their sea voyages. Our Lady of Good Help once looked out on seafarers, and now she looks on those making their way to the downtown core after shelling out too much for parking, but she still looks on, and welcomes, all.

But seeing that the original church was built the year of his death (1675), Marquette would not have known this Mary, so we continued. We found ourselves at Trois Rivières, at the massive shrine to Our Lady of the Cape (Notre-Dame-du-Cap). Marquette might have seen the original chapel, built in 1659. It was here, one new book reports, that he learned the Indigenous languages that equipped him for his mission. A new church was constructed on the site in 1879 when, despite the mild winter, a mile-and-a-half-long ice bridge miraculously formed, enabling building materials to be transported from the mainland. No such miracle was reported for the present concrete structure built in 1964, but its spacious interior welcomed us. Nevertheless, we sensed that Marquette’s Mary was still ahead of us.

I had long heard Québec City described as the most European of American cities, which—I can say having now at last visited it—gives far too much credit to Europe. On the contrary, it is European cities that sometimes equal Québec City, which combines the dramatic staging of Monemvasia with the intimate streets of Rothenberg. She is situated on the St. Lawrence as Istanbul is on the Bosporus, and unlike most European capitals, she boast a nearly three-hundred-foot waterfall just a short drive from her walls. And like the most beautiful ancient European cities, Québec City honours the Virgin. In the lower city, we visited Our Lady of Victories. Notre-Dame-des-Victoires was constructed in 1687 on the very site of Samuel de Champlain’s original 1608 habitation. It got its present name when the French beat back the British at the Battle of Québec in 1690. When the British were defeated again in 1711, the name was pluralized to Our Lady of Victories. Even though the church was destroyed by the British at the Battle of the Plains of Abraham in 1816, the name “Victories” endures on the reconstructed church, as if to suggest that Christian victory transcends the military kind. Mary, it seems, is not only Our Lady of Victories but Our Lady of Defeats as well.

Indeed, when one looks at the French settlement from the perspective of loss, other Marys take centre stage: not the glitzy image of the Immaculate Conception at the Cathedral Basilica in the upper town, built on the site of a chapel erected by Samuel de Champlain in 1633, and now known as Notre-Dame de la Paix (Our Lady of Peace), but the Marys that don’t make it into the tour books or even the pilgrim guides.

I found her only because all we could afford was a hotel near the airport. As we exited downtown, we got some sense of the countryside that once surrounded the city, despite the sprawl. One of the steeples was calling me, the Parish of Our Lady of the Annunciation, and so I answered. My wife agreed to watch the kids, hoping they would not notice the pool at the adjacent hotel we didn’t spring for, and I made the short drive to the prominent steeple. The church was closed, but what I found was better. It was a lovingly reconstructed wooden shrine, replicating one on this very site from 350 years ago, precisely the year of Marquette’s journey. While Marquette may not have been here, one of his associates was, and so I assumed this was as close to Marquette’s Mary as I was going to get. Marquette gave himself completely to the First Nations of this continent. One scholar describes how he “spent the majority of his [written missionary] narrative describing not how he took possession of the Illinois, but rather how the Illinois ceremoniously took possession of him.” Marquette’s colleague Pierre-Joseph-Marie-Chaumonot (1611–1693) continued this mission to the Huron-Wendat in the same spirit at this very spot, well outside the comparative splendour and security of Québec City itself.

Our Lady of Loreto is as famous as they come for Marian shrines. Legend has it that the Holy House—the very one in which the Annunciation took place—flew from Nazareth to the Balkans, and then, after one last leap across the Adriatic Sea, finally rested at Loreto in Italy. (Whatever we make of this story, a better metaphor for Christianity’s confident westward course is hard to conceive.) The future missionary Chaumonot went on pilgrimage to the Holy House in Loreto, Italy, as a young and wayward man. He was not his “best self” when he arrived. He was dishevelled, barefoot, wild-haired, smelly, and derelict, as dirty as the pilgrims in Caravaggio’s Madonna dei pellegrini. But the pilgrimage transformed him. And so, when Chaumonot found himself assigned as a Jesuit missionary to the Huron-Wendat in New France, he reconstructed the Holy House in gratitude. So it was that the Holy House flew to North America as well. And now, 350 years later, the bare outline of the Holy House built by Chaumonot has been reconstructed with humble timber in the shadow of a proud stone church. The Our Lady of Loreto statue that once stood there is replicated with a simple photograph pasted on wood, and the extent of the original structure’s walls is marked by a yellow line that encroaches on precious suburban parking spots. A structure that was once surrounded by Huron-Wendat longhouses is therefore now kept company by Subarus, Volvos, and Saabs.

This makeshift chapel meant to commemorate Chaumonot’s mission is no overconfident Our Lady of Victories. Owing to the rivalries triggered by European settlement, the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) pursued the Huron-Wendat mercilessly, forcing their flight. After the settlement of Sainte-Marie on Georgian Bay was attacked, some of the Huron-Wendat fled eight hundred miles to the safety of Québec City. As Indians, they were often not welcome. The Jesuits worked to bring the Huron-Wendat in as refugees, but the casualties of the Iroquois Wars were many. On one occasion, the Haudenosaunee piled seventy-one captive Huron-Wendat, mostly women and children, into canoes and processed them before the city walls to mock the residents, adding to the taunt by forcing the victims to sing. The Huron-Wendat of Sainte-Marie lost half of their population in only four years (1656–1660).

The Holy House I had discovered, therefore, emerged after a time of calamity, and it was constructed only because this rivalry had finally ceased. Moreover, in a startling act of reconciliation, the Haudenosaunee were welcomed into this new mission settlement. As Karin Vélez reports in her outstanding book on Loreto, a 1673 report from the Jesuits boasts not about Jesuit exploits but about the Huron-Wendat: “Our Hurons, themselves poor, have shown [such charity] to clothe, house, feed and even adopt” these Haudenosaunee, an act “all the more pure and heroic, as they have received so much bad treatment from the nation.”

That wampum confirmed in me a deep suspicion: racial reconciliation, the coveted prize of both colonial empires and modern global democracies, might actually be impossible without the cross.

Almost as if to prove this miracle, the next day as we toured the nearby Huron-Wendat Museum, my wife pointed to a wampum belt that showed the Huron-Wendat and Haudenosaunee reconciled. It was a gift offered by the Huron-Wendat to the Mohawk (a subtribe of the Haudenosaunee) who had decimated them. The white and purple mollusk shells were lovingly woven together, as were the Huron-Wendat and the Mohawk at the Lorette site itself. That wampum confirmed in me a deep suspicion: racial reconciliation, the coveted prize of both colonial empires and modern global democracies, might actually be impossible without the cross.

Witnessing this exquisite covenant of mercy, my family and I realized we had finally found the Virgin Mary to associate not only with Marquette but also with the First Nations who hosted him. In the Notre-Dame-de-Lorette church just outside the museum, a statue of Our Lady of Loreto continues to be honoured by the Huron-Wendat today. They consider her not a missionary’s imposition but their own mother. Vélez deftly dismantles the assumption that such an embrace is due only to the mechanics of colonization. Devotion to Our Lady of Loreto “was never simply a battle between high-ranking orthodox authority versus less elite, popular masses,” Vélez insists. “The expansion of Catholicism cannot be adequately explained as either top-down or bottom-up. There were multiple, simultaneous modes of regeneration stemming from, and entangling, all corners of society.” So it was that Our Lady of Loreto adopted the Huron-Wendat and their former enemies the Haudenosaunee, as well as the French, as her own. The Holy House, it turns out, was big enough for them all.

This Indigenous embrace of the Virgin was in turn reflected back to Europe. When the Catholic bishop of Montreal decided to return to Europe and visit Chartres in 1841, he was stunned to discover in the crypt a wampum belt from the First Nation he knew so well. It was a gift from Huron-Wendat devotees to the Virgin of Loreto from the mission just outside Québec City. The wampum, which survives at Chartres to this day, reads Virgini Pariturae Votum Huronum (Gift from the Hurons to the Virgin who shall give birth).

It turns out that on this journey we did not find Marquette’s Mary—we found a Huron-Wendat Mary, and a Mohawk Mary, and a Mary that can belong to the descendants of settlers as well. Marquette had to share the spotlight with the First Nations he loved. Back at Ignace, where Marquette’s body is buried, a remarkable record of one Christmas celebration even elevated the Huron-Wendat to royal status. The 1679 Jesuit Relations tells of a ceremony honouring Our Lady of Loreto at St. Ignace:

The Hurons, including those who were not converts, split into three large groups, each with a tribal leader wearing a crown and carrying a scepter to represent the three kings and accompanied by the sounds of trumpets. Proceeded by a banner carried on [a] standard depicting a star on a sky-blue field, the three groups marched to the church, where they presented gifts at the grotto and prayed. [The priest] then wrapped the [Loreto] statue in a fine linen cloth, and followed the procession, this time led by two Frenchmen carrying a banner depicting Mary and Jesus, to the Huron village. Once there, all of the Hurons, including those who had not converted to Christianity, participated in a dance and feast.

Not long after we returned to our home in Wheaton, Illinois, we remembered that Our Lady of Loreto has long been honoured in our town as well. But the sisters once associated with this devotion have sold their property, and we have slowly watched their once-flourishing Catholic convent, including its beautiful chapel and statue of Mary, get dismantled. But no matter. Maybe we Protestants—or at least we Anglicans—can help keep devotion to Our Lady of Loreto in this region alive. After all, it was in my home of Illinois where Marquette originally preached the message of the gospel to thousands of Illinois Natives in 1675, accompanied by banners of the Virgin Mary; and it was the Illinois who gave some of the Huron-Wendat refuge when they were fleeing from the Haudenosaunee, making devotion to Our Lady of Loreto here especially fitting.

It turns out that on this journey we did not find Marquette’s Mary—we found a Huron-Wendat Mary, and a Mohawk Mary, and a Mary that can belong to the descendants of settlers as well.

Yet there are deeper reasons still for such devotion. Perhaps Our Lady of Loreto was embraced by the Huron-Wendat because she reflects the elusive maternal figure of Aataentsic in their cosmology, just as Guadalupe reflected maternal aspects (“Tonatzin”) of Aztec goddesses before Christianity. Such parallels need not be considered evidence of the paganizing of Christianity (though they can be that). Instead such parallels, G.K. Chesterton believed, are evidence of the Christianizing of paganism. Aataentsic, historians tell us, had an “evil nature,” but Mary presented a God who vanquished evil itself. The Huron-Wendat, like so many of the First Nations, recognized a deeper revelation of an ineradicable lovingkindness at the heart of Being itself, betraying that the violence of their enemies, or their deities, would not get the last word. Christianity offered not an elusive flash of grace in a frequently cruel pantheon, but a rugged and permanent mercy whose source was the Creator, whom the Huron-Wendat, owing to their belief in a supreme sky spirit, already knew.

Even while those who brought the message were themselves frequently cruel, they brought tidings of the God who vanquished cruelty, extinguishing it on the cross within himself. It may have been a new faith for the Huron-Wendat, but it confirmed the best moments in their old one. “I have not come to abolish . . . but to fulfill” (Matthew 5:17). So it was that shifting glimpses of maternal aspects of the deity culminated in the bewildering fact that God, like all of us in our infancy, was dependent on the kindness of a mother too.