T

The year I came across Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger’s Eschatology was 1987 or 1988. I found it on the bottom shelf of a bookstore that is no longer there on Columbus Avenue in New York. Before that I had seen and feared Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, his face looking out solemnly from the cover of The New York Times Magazine in 1985. The Times piece explained that John Paul II and his prefect were articulating and clarifying doctrinal parameters that many of “the faithful” found problematic. Though I was not practicing at the time, I considered myself one of those “faithful.” The article made me uneasy.

I had long ago decided, in spite of a tenacity of belief in Jesus, to forsake Catholicism altogether. Better to leave than to sit there every Sunday and receive Communion knowing I was not living according to any standards implied in the gesture, even with my conviction that I was in front of the Real Presence.

A few years later I had finished a master’s degree and was working at Bellevue Hospital. I spent my free time wandering any part of the city I could think of where books were sold, hoping to find another collection of short stories that would inspire me to go home and write—something I was not managing to do.

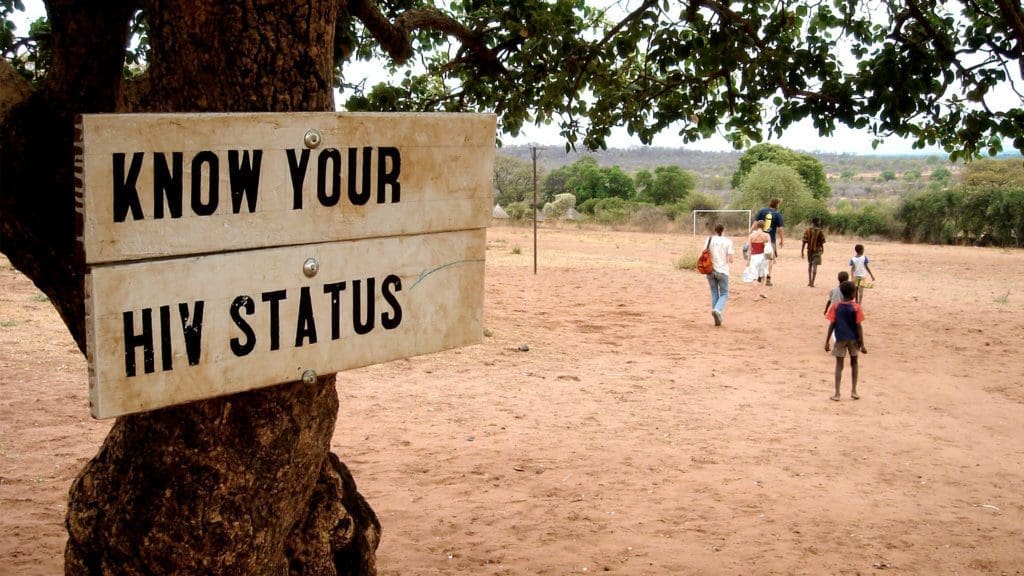

The afternoon I picked up Eschatology was different. I wasn’t looking for short stories. I was looking for an answer. An existential vertigo had crept up on me similar to that of Salinger’s Holden Caulfield when he fears falling as he steps off the curb on Madison Avenue. I was a clinic administrator at Bellevue in the midst of the AIDS crisis and had watched numerous gay men and intravenous drug users deteriorate either slowly or quickly depending on their individual pathologies and T cell counts. I had weathered the death around me quite well until one day when a patient came in who was not part of the statistics. She was a thirty-five-year-old woman in business clothes and a trench coat, and she had contracted HIV from one relationship. Her T cells were at an all-time low, although she showed no evidence of opportunistic infections at that point. I set her up for a blood draw for the doctor she was seeing, a friend and colleague. The following week I asked him how she was doing. Shortly after her visit, I learned, she’d been admitted to the hospital and was already dead.

I swallowed hard at the news. She hadn’t fit the bill: no worn 501s, no look of a hangover from late-night bars on West Street, no sense that she’d slept around or was part of the oversexed, drugged culture of gay men in the seventies and eighties. Only a sideliner who had fallen in love with a gay man who’d fallen in love with her back and had not realized he had the capability of ending her life. You braced for death with the addicts who were noncompliant with treatment and with the men who insisted on sleeping around “protected” even though continued promiscuity has a way—protected or not—of wearing down the body’s immunity even in healthy people. But I could not reconcile myself with the fact of this woman’s death. I left the job soon after. My boss, a woman dedicated to caring for the population we served, understood when I told her I couldn’t do it anymore.

It was around that time one afternoon on Columbus Avenue when I picked up Ratzinger’s book. I didn’t even know what “eschatology” meant; something just drew me to the word. It took me little time, however, to find what I needed to know from this Catholic cardinal whose name would never again make me cringe. He put into systematic theological perspective my anxieties about what exactly happens to us when our heart stops and our brainwaves cease:

Behind the apparent diversity of ideas, patient investigation can discern a unified fundamental perspective. In death, a human being emerges into the light of full reality and truth. He takes up that place which is truly his by right. The masquerade of living with its constant retreat behind posturings and fictions, is now over. Man is what he is in truth. Judgment consists in this removal of the mask and death. The judgment is simply the manifestation of the truth. Not that this truth is something impersonal. God is truth; the truth is God; it is personal. There can be a truth which is judging, definitive, only if there is a truth with the divine character. God is judge inasmuch as he is truth itself. Yet God is the truth for us as the one who became man, becoming in that moment the measure for man. And so God is the criterion of truth for us in and through Christ. Herein lies that redemptive transformation of the idea of judgment which Christian faith brought about. The truth which judges man has itself set out to save him. It has created a new truth for man. In love, it has taken man’s place and, in this vicarious action, has given man a truth of a special kind, the truth of being loved by truth.

That day, the white-haired German I had prejudged as a doctrinal inquisitor became a father to me. His wisdom gave me an unsentimentalized theological understanding of my own mortality while disabusing me of the notion that God wanted to condemn me. At twenty-seven, my takeaway was maybe inchoate but nevertheless sincere: Ratzinger’s description of death reassured me that if you live your life in a relationship with this mysterious God who talks to us in strange ways, you have nothing to fear. The words of a Flannery O’Connor character, that “every day is Judgment Day,” suddenly made sense: the moment of our death is only the direct continuation of this reality. Ratzinger’s lucid, methodical language made, for the first time, eternity comprehensible. The flawed theology of my late seventies Catholic high school education had presented us with varying theologians’ beliefs about whether the resurrection was real, making it seem like a wistful but childish myth. Our moral questions were unconsciously dismissed before we asked them; the God who determined them had become pre-emptively inconsequential. In Ratzinger I found an authoritative mind who presented me with something I could not dismiss as trite or sentimental. It was too well formulated, too appealing to somebody with a literary intellect, too resistant to dismissal because it was too intelligent.

That day, the white-haired German I had prejudged as a doctrinal inquisitor became a father to me.

The consequence of that afternoon came later, when I lost another friend to AIDS, Michael, a man in his early thirties who had fit the bill: vociferously gay, anti-Catholic, Jewish, promiscuous. The disease caught up with him, and I became his friend, I suppose, because I found the recklessness he’d lived with a curious thing, antithetical to my own character. I watched him whittle away to a skeleton, thrush coating his esophagus and digestive tract, and I watched him yell through one opportunistic infection after another at how unjust it was, and I watched him lose patience with my friendship because even as a lapsed Catholic I had some vague sense of charity and mercy toward the sick that smelled irrevocably Christian in a way that repulsed him.

Then a curious thing happened. He met a Jesuit—a mutual acquaintance—and they started getting together for coffee. I was disappointed with myself that somebody else had stepped in to draw him in. To my own chagrin, there was a conviction still lurking in the back of my mind. Fearful of his resentment, I didn’t have the guts to tell him I did believe death wasn’t the end for him. That would have meant I needed to say the word “Jesus” to his face.

The day I attended shiva and his funeral, I stood next to his mother, gazed at his body, and said, “Zeldy, why does he have a black rosary in his hands?” She looked at me wistfully, grateful for my persistence in friendship with him, and told me she approved of anything that made him able to face what he had to face. I turned from her in shame at the fact that, fearful of Michael’s disdain, I’d suppressed the impulse to offer him any hope. All along I’d felt that in his suffering there had to be a God who would redeem it. The sense of being apologetic for my own latent Catholicism started to dissipate.

It took one more death—Julian, a neighbour and friend in the apartment building I lived in. He was also a lapsed Catholic, a flower arranger from Georgia whose partner, later dead, had been a scenic designer on the crest of his first Broadway success. The morning he died his partner recounted to me, “He just lay down on the couch and said everything was getting dark.” I remember what I was wearing that day when I couldn’t take it anymore, as well as the question I had been unconsciously plagued by: Are You real or not? I was wearing a red plaid button-down shirt my mother had bought me one Christmas, a grey cardigan, and some light-green khakis, a favourite pair of pants I’d gotten at the winter sale at Barney’s sometime in the eighties. It was an overcast, humid, late fall day in Harlem. I remember all this because I left my apartment at 156th and St. Nicholas, walked to the A train, took it to 14th Street, and walked to St. Francis Xavier Church, where I found a young Jesuit and told him, “I don’t know what’s happening to me, but I think I should come back to the church.”

I knelt in front of a very large and lifelike crucifix and looked up at the face of Christ, and it hit me for the first time that he was an actual person, and that the year of his life when he died on the cross was not far from my own.

Youthful and astute, affectionate and full of good humour as I listed the things I needed to confess, the Jesuit told me, “I don’t know what’s happened to you either, but it looks like you’ve had some kind of conversion experience.” He told me to stay with it, not to be afraid, and to see what was happening. I was sweating, my upper body wincing the way it does when a tart flavour you weren’t expecting hits your mouth. I had a sense of terror, but it was coupled with another sense—that there was some presence in this who was guiding me through whatever it was so I wouldn’t get overwhelmed. And I thought, Oh God, you are real.

I hung around the church after that and waited for a Mass because I wanted Communion. I knelt in front of a very large and lifelike crucifix and looked up at the face of Christ, and it hit me for the first time that he was an actual person, and that the year of his life when he died on the cross was not far from my own.

That year is one I do not confuse with any other: 1989.

It was not until 2011 that I bought an actual copy of Ratzinger’s Eschatology. I didn’t need to in 1989. The words I read on the floor of Endicott Booksellers had done the job they were intended to do. I have gone to Mass every day since that day in November of 1989, unless my schedule makes it impossible. The Jesus I’d been ashamed of talking about wasn’t holding it against me. I sometimes ask myself if, when those two friends—Michael and Julian—had exited their bodies, the same power that had been working in me had worked in them through their illnesses, and if they were watching me there in my apartment in my favourite khakis, on my side of the white tunnel everybody talks about, pulling at the stray threads hanging from my spirit to yank me in another direction.