W

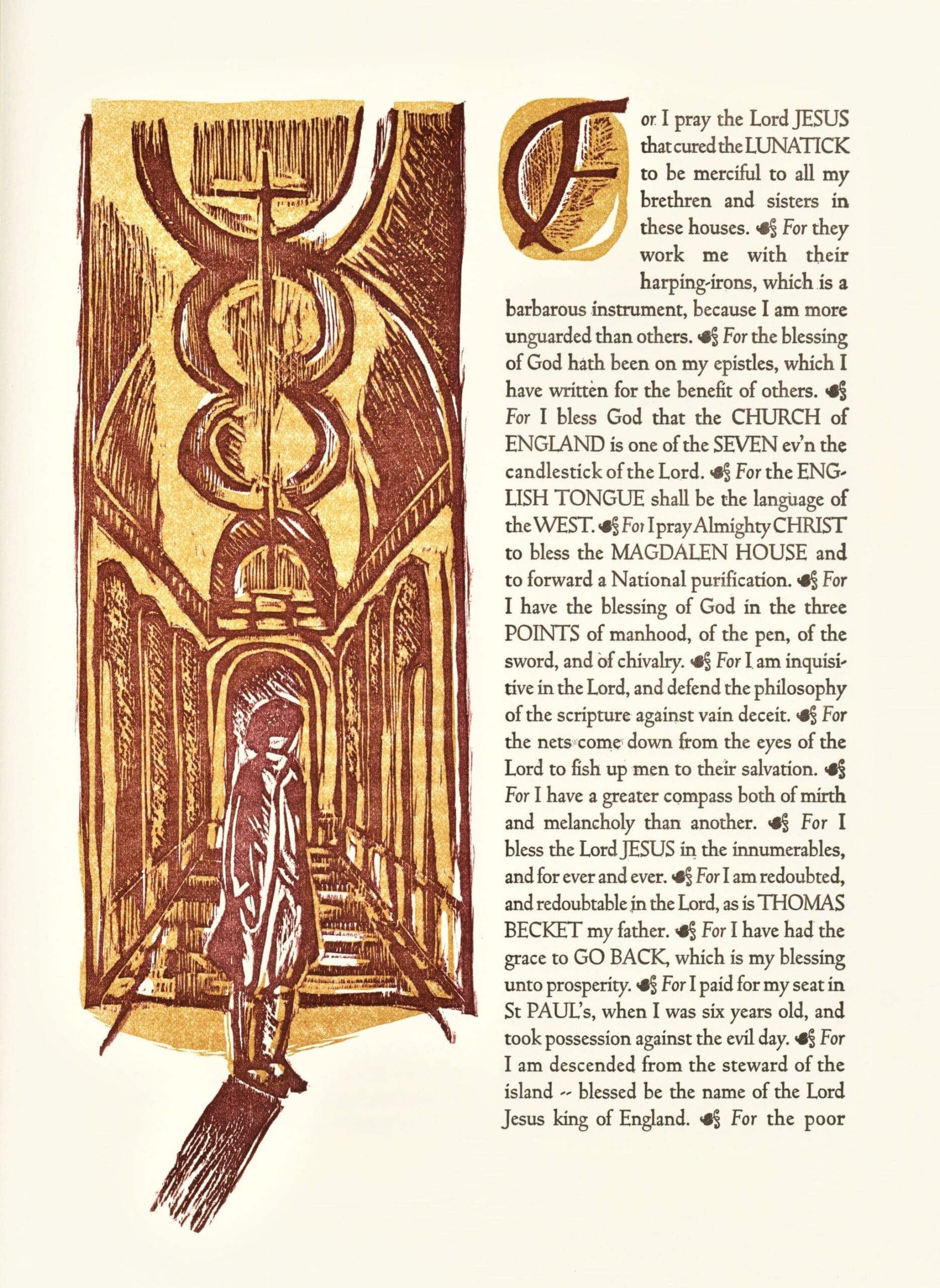

What a gorgeous edition of Christopher Smart’s weirdly wonderful poem Jubilate Agno. One of my first published essays — an excerpt from my dissertation — was on Smart, one of the eighteenth century’s most prominent “mad poets.” Samuel Johnson loved Smart, as this passage from Boswell’s life shows:

Madness frequently discovers itself merely by unnecessary deviation from the usual modes of the world. My poor friend Smart showed the disturbance of his mind, by falling upon his knees, and saying his prayers in the street, or in any other unusual place. Now although, rationally speaking, it is greater madness not to pray at all, than to pray as Smart did, I am afraid there are so many who do not pray, that their understanding is not called in question.”

Concerning this unfortunate poet, Christopher Smart, who was confined in a mad-house, he had, at another time, the following conversation with Dr. Burney. — BURNEY. “How does poor Smart do, Sir; is he likely to recover?” JOHNSON. “It seems as if his mind had ceased to struggle with the disease; for he grows fat upon it…. I did not think he ought to be shut up. His infirmities were not noxious to society. He insisted on people praying with him; and I’d as lief pray with Kit Smart as any one else. Another charge was, that he did not love clean linen; and I have no passion for it.”

Recently on my blog: A ride in a time machine, my new book project revealed, and a reference work in progress: the ENCYCLOPEDIA BABYLONICA.

AND I have an essay in the new issue of The New Atlantis called “Resistance in the Arts.” Here I’m trying to understand how the flourishing of arts in certain times and places is related to the pressure of resistance — economic, social, and technological resistance. This is something I’ve been thinking about for a long, long time, because it seems to be that creators are at their most creative when they encounter certain kinds of obstacles in certain degrees. Too much resistance prevents works of art from being made at all, but too little resistance makes art flabby and characterless. In this essay I try to account for these phenomena more specifically.

If I were in London, I’d like to learn the basics of wood engraving at the St. Bride Library.

Austin Kleon on the value of keeping a diary.

The photographer Lee Miller, 1945, cleaning up in Hitler’s bathtub.

In 2020, I heard about a residential training school called the Colorado Center for the Blind, in Littleton. The C.C.B. is part of the National Federation of the Blind, and is staffed almost entirely by blind people. Students live there for several months, wearing eye-covering shades and learning to navigate the world without sight. The N.F.B. takes a radical approach to cultivating blind independence. Students use power saws in a woodshop, take white-water-rafting trips, and go skiing. To graduate, they have to produce professional documents and cook a meal for sixty people. The most notorious test is the “independent drop”: a student is driven in circles, and then dropped off at a mystery location in Denver, without a smartphone. (Sometimes, advanced students are left in the middle of a park, or the upper level of a parking garage.) Then the student has to find her way back to the Colorado Center, and she is allowed to ask one person one question along the way. A member of an R.P. [retinitis pigmentosa] support group told me, “People come back from those programs loaded for bear” — ready to hunt the big game of blindness. Katie Carmack, a social worker with R.P., told me, of her time there, “It was an epiphany.” That fall, I signed up.

To handle the “independent drop,” students must learn a set of skills, or really an orientation to the world, called “structured discovery.” What a fascinating concept, and applicable in every area of life. I’m already thinking about how I can get my students to practice structured discovery.

aows, Castle of the Templars

I said grace cannot prevail until law is dead, until moralizing is out of the game. The precise phrase should be, until our fatal love affair with the law is over — until, finally and for good, our lifelong certainty that someone is keeping score has run out of steam and collapsed. As long as we leave, in our dramatizations of grace, one single hope of a moral reckoning, one possible recourse to salvation by bookkeeping, our freedom-dreading hearts will clutch it to themselves. And even if we leave none at all, we will grub for ethics that are not there rather than face the liberty to which grace calls us. Give us the parable of the Prodigal Son, for example, and we will promptly lose its point by preaching ourselves sermons on Worthy and Unworthy Confession, or on The Sin of the Elder Brother. Give us the Workers in the Vineyard, and we will concoct spurious lessons on The Duty of Contentment or The Moral Aspects of Labor Relations.

Restore to us, Preacher, the comfort of merit and demerit. Prove for us that there is at least something we can do, that we are still, at whatever dim recess of our nature, the masters of our relationships. Tell us, Prophet, that in spite of all our nights of losing, there will yet be one redeeming card of our very own to fill the inside straight we have so long and so earnestly tried to draw to. But do not preach us grace. It will not do to split the pot evenly at four a.m. and break out the Chivas Regal. We insist on being reckoned with. Give us something, anything; but spare us the indignity of this indiscriminate acceptance.