I

I entered the New Age bookstore and was welcomed by the sound of warbling gongs, the smell of patchouli oil, and the sight of ample spiritual merchandise. Besides the standard Wiccan book offerings, a Minoan Tarot deck promised to connect one with the goddess in her ancient Cretan manifestations. I thought of striking up a conversation with the smiling proprietors, asking them if they knew that Valentin Tomberg, in his classic book Meditations on the Tarot (1985), had successfully transformed the cards into tools for Christian evangelism. But then I thought better of it. Against all my protestations, I was here to force myself to give the goddess a chance.

By some accounts, the postmodern goddess movement was launched roughly a generation ago, when Carol Christ (1945–2021) gave her “Why Women Need the Goddess” address at the Great Goddess Re-emerging conference at the University of Santa Cruz in 1978. Now nearly fifty years later, I was impressed that the movement still seemed to be going strong. I saw copies of the Yoga Sutras and the Bhagavad Gita for sale. The Bible, understandably enough, was absent, but the music over the speakers had the earnestness of the Christian praise songs I had grown up with as a teenage evangelical convert. “Love, joy, and peace” resounded the confident chorus, with the follow-up, “These are the gifts of the Goddess. Are you ready to receive?”

“Sorry,” I thought, “but I’m not sure that I am.” There were a lot of goddess statues around me, and I wasn’t sure to which of them I should direct my apology. But my hesitations were honest ones. Whether or not the criticisms of the goddess movement have always been fair, they have been furious. Elizabeth Gould Davis’s claim in The First Sex (1971) that men are a criminal genetic mutation from an originally female race, or goddess movement leader Z. Budapest’s claim that her mother (like Jesus himself) was born without fertilization from a male, was not a very solid foundation on which to build. In her 1979 neo-pagan classic The Spiral Dance, the Wiccan celebrity Starhawk gained attention for the goddess movement by claiming “an estimated nine million Witches” had been executed by an intolerant Christian regime. Brian Levack’s scholarly study The Witch-Hunt in Early Modern Europe puts the number of these tragic deaths at approximately forty-five thousand. Called out for inflating figures two hundredfold, Starhawk, in the updated twentieth anniversary edition of The Spiral Dance, admitted (I am glad to report) that her figure of nine million “is probably high.”

But the embarrassments were just beginning. The entire history of Europe’s supposed “age of the Mother Goddess,” where women enjoyed power and prestige before the onset of patriarchy, has been, according to Rosemary Radford Ruether, “totally discredited among professional anthropologists and archaeologists.” Ronald Hutton argued that in its heyday of the seventies and eighties, “British pagan witchcraft was often an uncomfortable place for an intellectual: for one with a state-of-the-art knowledge of history and archaeology it had become virtually uninhabitable.” We might call this condition, with a nod to the American evangelical historian Mark Noll, the scandal of the Wiccan mind.

As if that were not a sufficient debunking, Cynthia Eller, in Gentlemen and Amazons (2011), went on to show how the myth of a lost matriarchal age has long been employed by men to prove that society had advanced beyond matriarchy, making this view fodder for “fascists, male supremacists, and misogynists championing the evolutionary fitness of male dominance.” Even so, it is fair to say that many goddess enthusiasts are untroubled by any of this. Mary Daly (1928–2010), after all, counsels women to fabricate evidence where it doesn’t exist. In Gyn/Ecology (1978) she cites approvingly the women in Monique Wittig’s radical feminist revenge novel Les Guérillères, who demand, “Make an effort to remember. Or, failing that, invent.” Some more recent goddess enthusiasts, however, conceding the false start and the archaeological untenability of the “age of the Mother Goddess,” plead for future caution.

Even so—I assured myself in the bookstore—the goddess movement is no doubt responding to a genuine deficit. There were no satanic ritual kits for sale (as some might unfairly assume). It would not be terribly controversial to assert that masculinity has been overemphasized in recorded human history, and especially in North American Christianity more of late. Considering the disgust this brand of macho faith has provoked among so many, it is reasonable to assume that New Age bookstores like this might be receiving more traffic from disaffected Christians. “Penance for toxic masculinity,” I insisted to myself, stamping my foot unconvincingly, “starts here.”

I scanned the titles—Reclaim Your Dark Goddess, Queering Your Craft, Entering Hekate’s Cave, Warrior-Goddess Training: Companion Workbook. I tried to understand why a “Pro-Choice, Pro-Equality, Pro-Democracy” placard was leaned up against a statue of Poseidon, or why a statue of the Virgin Mary was tucked between replicas of the Venus of Willendorf and the Gundestrup cauldron. My skepticism began to reassert itself. Any spell this bookstore could cast on me was dissipating. If the goddess and I were going to get along, I needed more.

Hoping to give the movement as fair a shake as possible, I made a visit to Manhattan’s Metropolitan Museum of Art to encounter the goddesses themselves in their original form. Perhaps examining the actual goddess statues that were once worshipped, not just the replicas on offer in the bookstore, would enable them to withstand the criticism goddess enthusiasts have recently faced. I therefore entered the museum sincerely, as might a devotee, ready to receive.

Morning at the Museum

It was early, so far as American museums go at least. The sun was still low enough in the sky to be obscured by the Beaux-Arts towers at my back. I beat the gaggles of high school students snapping selfies on the Fifth Avenue steps. I crossed the museum threshold and produced the suggested admission fee. The swelling crowd did not unsettle me, for I could be sure that few would follow me to my destination. Just up the Met’s grand staircase and to the left are the Cypriot galleries, which I entered, as expected, alone. While not the museum’s most popular rooms, the artifacts here from the Mediterranean island of Cyprus remain the archaeological core from which the rest of New York’s encyclopedic art collection emerged. Here I could behold figures that might be considered testimonies to a lost era of female empowerment, which is to say, in these galleries the goddess awaited.

I positioned myself before one lonely figurine with uplifted arms. Even if Jean Shinoda Bolen’s claim that such figures represent a “matrifocal, sedentary, peaceful, art-loving, earth- and sea-bound culture that worshipped the Great Goddess” have been undermined, I tried to appreciate the statue anyway. The figure is understood to be the Canaanite goddess Astarte, or—to use her Hebrew name (owing to her biblical cameos)—Ashtoreth, the female consort of the male storm and fertility god known as Baal. The accomplished archaeologist William Dever wrote that when goddesses such as these are acknowledged, “the spirit of the Great Mother will at last be freed”—the spirit, he goes on, that was “driven underground by the men who wrote the Bible.” Maybe there was something to this elusive female divinity after all. One goddess-friendly publication describes such upraised hands as a gesture of “greater soul,” which does not seem entirely unfounded. The name Astarte simply means “womb,” an innocent-enough designation. She is sometimes connected to the Canaanite goddess Anat, or more broadly to Inanna (Ishtar in Akkadian). These goddesses formed a Mesopotamian sorority of sorts, coalescing around the planet Venus. Astarte is the goddess of both love and war, which is to say, she is both appealing and assertive, and even if this particular sculpture does not capture her on her best day, ancient accounts testify to Astarte’s captivating beauty. With the ravages of time, accident, and religious fervour that have marred sculptures like this, we are fortunate that she even comes down to us at all. Standing before her glass case, not without reverence, I attempted to make up for what she lacks with my imagination.

Though these were the Cypriot galleries, reverence for Astarte, it appears, was an import to Cyprus from Crete, that island where, goddess enthusiasts Jules Cashford and Anne Baring claim, “the great goddess was experienced as a flowing, dynamic energy.” Indeed, goddess tourism to the island of Crete continues to be a serious industry, where modern pilgrims go to experience her energy firsthand. Nearby is a figurine believed to be a priestess. She holds a dove, preparing—it is thought—to offer the bird as a sacrifice to Astarte. For many, this portrait of women officiating in the worship of female divinity seems a far cry from monotheistic religions with normative male priesthood. As Merlin Stone puts it in When God Was a Woman, “We may find ourselves wondering to what degree the suppression of women’s rights has actually been the suppression of women’s rites.”

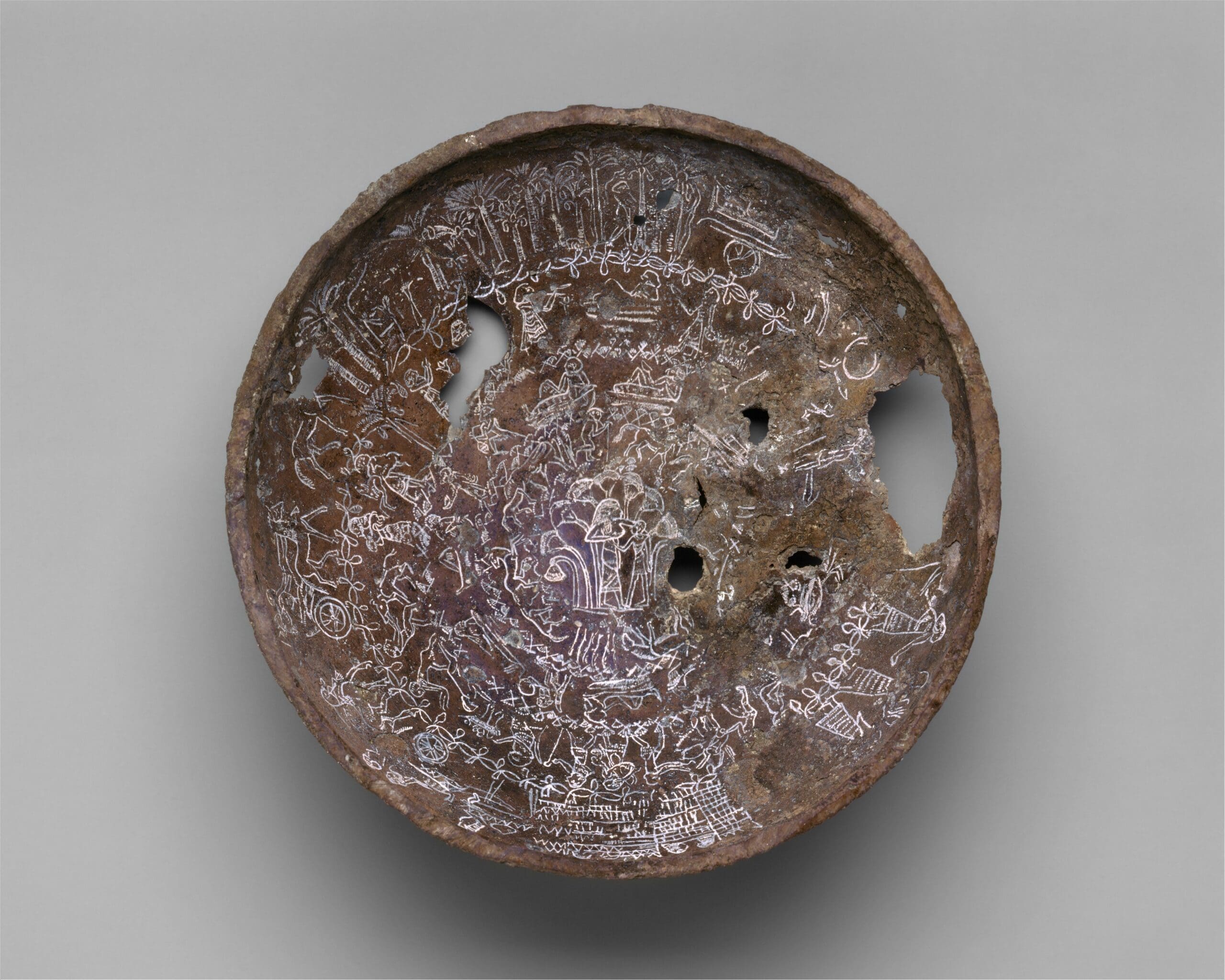

Some have suggested that Astarte and her cult lacked the tenderness that many today associate, rightly or wrongly, with the feminine. Erich Neumann’s frequently cited study of such goddesses insists that “all three of them [Astarte, Anat, and Ashtoreth] are sinister goddesses of sex and war, whose bloodthirstiness rivals even that of Hathor and the Hindu Kali.” But the Cypriot galleries appear to contain an answer to that accusation. In a bowl from 675–625 BC, the Egyptian goddess Isis compensates for Astarte’s aggression with an undeniable tenderness. Surrounding the bowl’s central figure are horses, bulls and herdsmen, kings reclining on couches, musicians, and men (with a few women) bearing sacrificial gifts. Chariots and battlements flank the bowl’s outermost perimeter—the instruments of war. Which is to say, the bowl presents the bustling activities of a male-dominated world; but it is the centre that matters. There Isis shows her breast to her son Horus, urging him to receive her nourishing milk. The bowl seems a fitting illustration of the forgotten place of women who, in one time period at least, could push the cacophonous noise of men to the perimeter.

Next I made my way to the star of the collection. She is a local Cypriot deity, better known to us as Aphrodite, a name probably derived from Astarte. Indeed, Aphrodite’s temples were sometimes built over Astarte’s to emphasize continuity. This life-size limestone goddess dates to the fourth century BC, the era of Alexander the Great. Not yet the completely nude goddess of love she would become in later Greek art, here Aphrodite is clothed and fearsome. She is the heiress of the Sumerian Inanna and Ishtar, the Canaanite and Phoenician Astarte and Anat, and maybe even Isis as well. She holds not Horus but Eros, in the form of a child, in her left hand. Her headdress, fittingly enough, displays nude women, fearlessly exhibiting their sex.

Astarte had her sisters, and Aphrodite did as well. Artemis looms nearby in the Cypriot galleries too, dating to the same era. Her quiver gives her away. The temples of Artemis and Aphrodite were sometimes placed together, emphasizing their complementarity. Admittedly this statue of Artemis is rated G; she is not covered by breasts and testicles as she is in more famous depictions. She stands regally and holds not Eros but what appears to be a floppy-eared fawn or lamb. Though fertile, she chooses not to have children, opting—as do many in our own era—for a pet instead, which is fitting for a goddess who protected all species. If Aphrodite was for love, Artemis was single by choice. Even the suggestion of her availability was enough to get one unfortunate hunter, Acteon, turned into a stag (and then killed by his own hounds). A massive capital from one of Artemis’s ancient temples has been installed in the Met’s Greek and Roman galleries below the Cypriot galleries, offering a sense of the powerful scale of such lost feminine sanctuaries, which—according to some sources—fused the worship of Isis and Artemis into one. The Met’s Artemis capital, along with this statue, might be considered sad testimony to the once regnant power that chauvinist society has crushed.

In sum, the gifts of the goddess that the Manhattan refuge of the Cypriot galleries offer are these: Astarte, fecund and fierce; a confident, wide-eyed priestess; Isis, the eye of a feckless masculine hurricane; Aphrodite, the goddess of love herself; and Artemis, mistress of nature and slayer of men. (Not penitent men like me, of course—other men.)

A Woman at the Tomb

But before I made my exit, one last image in the Cypriot galleries arrested my attention. This woman was no goddess. She was carved for a fourth-century-BC limestone grave marker: a simple woman in grief. Youthful, she may be a testimony to an actual woman whose life was cut short. Her sorrow reached through the ages, and she interrupted my planned departure.

This statue brought to mind the actual women in the societies that worshipped goddesses, not the goddesses themselves. Perhaps a woman similar to the one standing before me sacrificed her children to the goddess Astarte. Puzzlingly enough, in Did God Have a Wife?, the very same book that hails goddess images as liberating for us today, William Dever also indicates in passing that “[at Tophet] thousands and thousands of burial urns have been unearthed containing the burned bones of infants, a vow fulfilled to Tanit [the Phoenician form of Astarte] or Ba’al Hamon.” Evidence like this might intimate why the Bible is not terribly enthusiastic about Astarte.

I allowed the statue in front of me to represent an actual woman who had lost her husband in warfare. Most would not laugh at such misfortune. But there is good reason to believe that Anat the Destroyer (a goddess often connected to Astarte) would have. As one famous ancient source puts it:

Anath gluts her liver with laughter.

Her heart is filled with joy

For in Anath’s hand is victory.

For knee-deep [she] plunges in the blood of soldiery

Up to the neck in the gore of troops.

Some read this hymn as a cry of fierce female independence. But warmongering poetry like this might also cause us to wonder if the Astarte statue in the Cypriot galleries was made not for women but for men. Scholars of Sumer have not hesitated to connect the cult of Inanna to modern pornographic violence. Warfare, the “festival of manhood,” explains Tikva Frymer-Kensky, was “Inanna’s dance. . . . Inanna/Ishtar unites erotic attraction with aggression, love with rage, desire with combat. . . . Inanna devastated the land that would not worship her.” Perhaps Inanna devastated the families of women like the mourning Cypriot woman I was standing in front of as well.

So it was that my enthusiasm for the goddesses in the Cypriot galleries began also to be devastated. Even Isis faltered. I wondered if the silver bowl with Isis at the centre was not empowering at all. Instead, it showed her to be imprisoned by the concentric rings of male business. After all, a large part of Isis’s formal mythology shows her chasing around and rehabilitating her brother/husband Osiris’s faltering penis, which is what many men consider a woman’s job to be. None of this is surprising considering the fact that Isis is a lower-ranking goddess set in a pantheon whose highest deity, Atum-Ra, masturbates the world into existence. The Egyptian pantheon in which Isis finds her place (according to Tom Hare’s ReMembering Osiris) illustrates the “sovereignty, paternity, dominion” of men.

Circumambulating the statue of the mourning Cypriot lady, one might wonder perhaps if she, or more likely a woman of lesser status, once served as a sacred prostitute. While some accounts of temple prostitution have been exaggerated, there is no question that it was one of the marks of Astarte’s worship, and Isis’s as well. When the cult of Astarte was absorbed by the cult of Aphrodite, the prostitution continued. That may be the reason, it turns out, why nude figures are emblazoned on Aphrodite’s headdress. We might call her the goddess of sex-trafficking. Perhaps this marks yet another reason that the statue of the Cypriot woman in front of me is so sad.

Still, if Aphrodite is compromised by prostitution, perhaps Artemis, regal and chaste, would offer comfort to this weeping woman. Unless her name was Iphigenia, who was sacrificed by Artemis to punish Agamemnon. Indeed, human sacrifice is a steady reference in Greek literature regarding Artemis, a tradition substituted later with animals and nicks on the throat. Records survive of human blood and gore associated with the cult turning some initiates (like the Christian convert Tatian) away. This was a fact that Aphrodite would have known well; her lover Adonis, in one telling of Greek mythology, was killed by none other than Artemis.

In sum, Astarte, Isis, Aphrodite, and Artemis served the privileged while utilizing the poor. They might stoke a victorious warrior, but could also mock the defeated. They might promise the gift of a child, only to require that child back in sacrifice. They might promise a man’s sexual fulfillment, but at the expense of the actual woman who would provide it. It is a division conveniently expressed by the wall between the goddess Aphrodite and the mourning woman that can be viewed in the Cypriot galleries at the Met today.

Mary’s Reply

Reeling from this disillusionment, I decided I couldn’t leave the museum altogether as planned. I burst the constraints of my agreed-on confinement to the realm of the goddesses. I escaped into the Renaissance galleries just a few rooms away. At random, I trained my eyes on a painting. It was from the late 1480s by the Venetian artist Giovanni Bellini. Here the partition between suffering mortals and the ineffable divine—fully intact in the Cypriot galleries—was pulled back. The blue of Mary’s garment straddled both realms at once, the heaven in which divinity dwells, represented by her son, and the transient reality familiar to us all, represented by the creamy Italian path-pierced townscape and the blue mountains beyond.

The fruit held by her son looked familiar. It echoed the perishable fruit held by the grieving woman on the Cypriot tomb. Christ looks past the curtain; his eyes fix on a cloud that portends his own forthcoming catastrophe. The three barren trees below morph into intimations of Calvary.

There was nothing like this in the Cypriot galleries. In this painting, I witnessed a transformation. I mean that in the technical sense. Like a modern electrical transformer, Mary’s yes turned the live currents of uncontainable divinity into sustaining energy and warmth. As the early Christian poet Ephrem the Syrian puts it:

And became a servant; he entered able to speak

And he became silent in her; he entered her thundering

And his voice grew silent; he entered Shepherd of all;

A lamb he became in her; he emerged bleating.

The Artemis holding the lamb in the Cypriot galleries, thanks to Bellini’s nearby painting, had been redeemed.

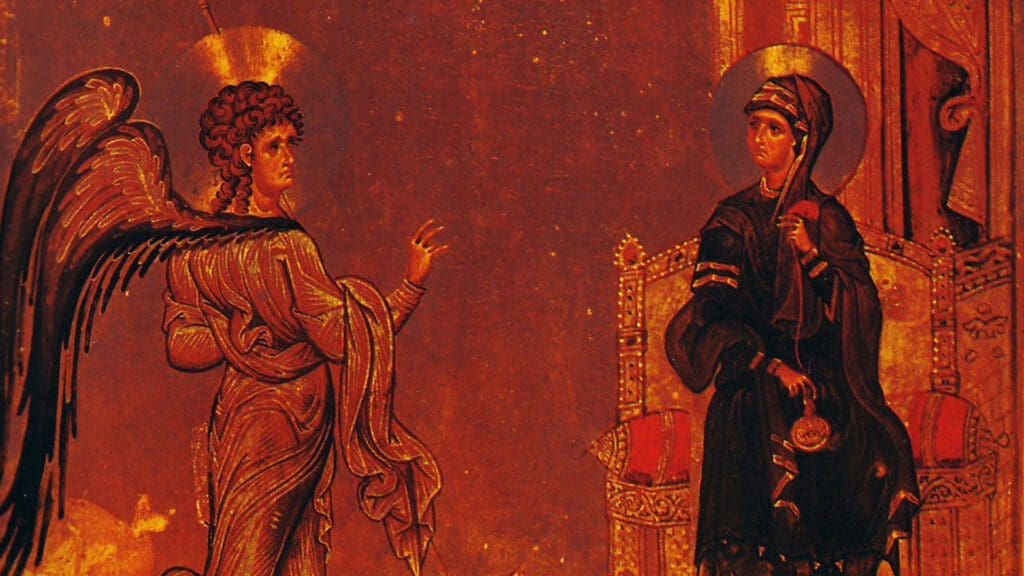

And so I kept wandering. The museum seemed to be beckoning me beyond the Renaissance galleries to take in everything it had to offer. In the lower Byzantine and medieval galleries, I saw how the prayerful posture of Astarte was not annihilated but answered in Mary, whose arms—in a sixth-century Byzantine censer also at the Met—are similarly upraised. In the nineteenth-century galleries, I saw how, in place of the child sacrifice sponsored by Astarte, Mary offered up the sacrifice that rendered future ones, whether human or animal, unnecessary: Ingres’s The Virgin Adoring the Host deliberately paints the last sacrifice of the Mass taking place in Mary’s womb, troubling the assumption that Mary did not participate in priesthood herself.

I burst into the medieval galleries, there to see how the tenderness of Isis was not erased but escalated by images of the breastfeeding Mary such as Paolo di Giovanni Fei’s Madonna and Child. But unlike pagan images, icons like this seemed equipped with some kind of advanced forcefield that could purify the lustful gaze of men.

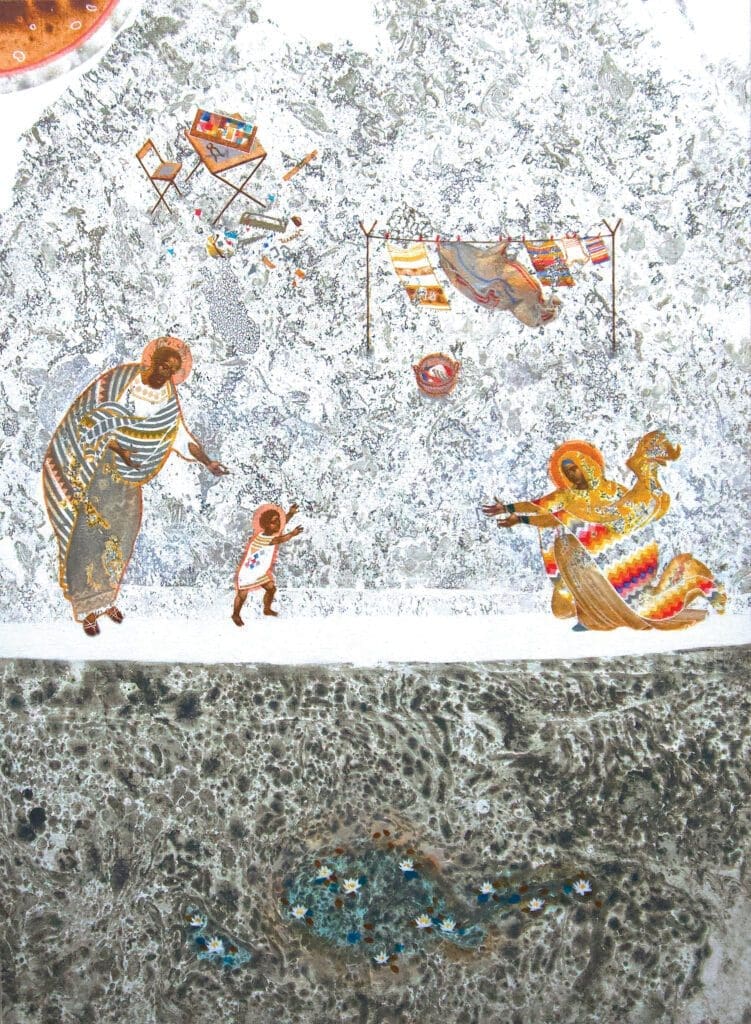

Emboldened, I made my way to the Northern Renaissance rooms. In the Marian tradition, the unexpected moments when Aphrodite mourned Adonis or when Isis mourned Osiris were seized on and expanded; Mary’s human grief could be full-throated and unrestrained precisely because of its forthcoming consolation in her son’s resurrection, a moment tenderly visualized by Juan de Flandes. Jesus and his mother seem to return to a moment of unexpected childlike joy, as if they are playing patty cake again. But now with a mature and unconquerable joy, with full knowledge this time that no empire would ever rip them apart. How many mothers who have lost their own children, I thought to myself, had this painting quietly consoled?

Still hoping to be fair, I decided to give Artemis one more chance. I made a last stop to the American wing of the Met, where the golden flesh of a nude Artemis, popularly known as Diana, dominates the courtyard. The signal masterpiece of the American sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, she was the indicator that America had at last equalled the aesthetic sophistication of Europe. I had grown up seeing a version of the same sculpture atop the grand staircase in the Philadelphia Museum of Art—if any goddess could win me over, this was the one. In Artemis: The Indomitable Spirit in Everywoman, Jean Shinoda Bolen credits the modern women’s suffrage movement to an uprising of the Artemis archetype. And here she was in front of me, her arrow poised to puncture the patriarchy (myself excepted) all over again.

But anyone who makes a pilgrimage to Seneca Falls, birthplace of the modern women’s rights movement, will find not a temple to Artemis but a Wesleyan chapel. And to this undeniable fact I can add something more. When Saint-Gaudens suggested his nude statue of Diana top the Women’s Pavilion at Chicago’s Columbian Exposition in 1893, the women refused. The largest suffrage organization by far, the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, was singularly devoted to Jesus and therefore protested any association with Diana imposed on them by men.

Into the City

So I tried, really I did. But when it comes to the goddess, I remain a wistful unbeliever, and I am at a loss as to how to convey this to those who still worship this ahistorical amalgamation today. I exited the museum, exhausted. The sun was now high in the sky, and the crowds on the steps, men and women together, were thick. I thought of how the biblical God, in contrast to paganisms then and now, did not masturbate or copulate the world into existence but spoke it into being. This God is beyond gender, and all of the men and women together who I saw before me were made in this God’s mysterious, irreducible image. I passed Park Avenue Synagogue. I thought of the monotheistic revolution, which required that the responsibilities of both male gods and female goddesses be absorbed by the God of Israel: “The Lord will march out like a champion, like a warrior he will stir up his zeal. . . . ‘But now like a woman in childbirth, I cry out, I gasp and pant’” (Isaiah 42:13–14). I thought of Wisdom, deliberately cast as female in the Bible, not a distant progeny of the supreme male deity as was Isis, but “the first of [God’s] works, before his deeds of old” (Proverbs 8:22).

The streets kept calling me onward. I passed the stately Brick Presbyterian Church, whose confessions still proclaim, “There is but one only living and true God, who is infinite in being and perfection, a most pure spirit, invisible, without body, parts or passions, immutable, immense, eternal, incomprehensible.” I stepped inside the Georgian Revival edifice to see how its imageless interior conveyed this unfathomable truth. And yet, despite the emphasis on God as pure spirit, worshippers there still proclaim that the unfathomable was “born of a Virgin.” I passed the Church of St. Ignatius Loyola, recalling the Catholic Catechism that declares God “is neither man nor woman.” Stepping within, I saw Mary in the apse springing forth from vibrant mosaic tendrils of coiling vine. For all its pretense of transcendence, magic—argues Valentin Tomberg in Meditations on the Tarot—really offers only a closed circle. Christianity is the actual spiral dance, for only the incarnation, thanks to the Virgin’s consent, “opens the closed circle and transforms it into a spiral.” Tomberg continues:

Nearby in the same church stands a replica of the famous Black Madonna of Montserrat. She presents not only the groaning earth, represented by the globe in her hand, but also the one through whom it was made, Jesus. He holds a pine cone, a symbol of inexhaustible fecundity and life.

La Moreneta, the little black-skinned one, is still honoured in the Catalan hills that once honoured Venus, and now—following my goddess tour of the Met—the same fulfillment took place in Manhattan. One might even say that before that black statue I felt the “flowing, dynamic energy” promised by proponents of the goddess. I thought of how sad it is that Christians fight so passionately among themselves over the status of Mary while the wider world, devoid of the witness it requires, replicates ancient mistakes. I thought of the onetime goddess enthusiasts I know who have come to love the Virgin Mary and Jesus, criticizing Christianity (Protestant and Catholic both) for making too little of her. I could recuse myself before the goddesses, but not before her. Five centuries ago, Ignatius of Loyola laid down his sword before the Virgin of Montserrat. I imagined myself doing the same, laying down the sword of inter-Christian polemics, along with any sword that unjustly persecuted witches in the past, or any women, within the church or without, today. I thought of my own sins against women, and I asked forgiveness from Mary’s son, who loves them, and me, so well.

I stepped outside again. The cramped quarters of the New Age bookstore, the enclosed Cypriot galleries, and the confined contours of the museum gave way to a crenellated canopy of high-rises. As the sun dropped over Central Park, I summoned from my memory a powerful spell. I began a most captivating incantation:

and my spirit hath rejoiced in God my Savior.

For he hath regarded

the lowliness of his handmaiden.

For behold from henceforth

all generations shall call me blessed.

For he that is mighty hath magnified me,

and holy is his Name.

As my whispered invocation continued, for a moment at least, the city’s mighty were “scattered in the imagination of their hearts.” The anonymous women of history, like the mourning women in the Cypriot galleries, were exalted, and the rich were “sent empty away.” As I ended with the Gloria Patri, even the skyscrapers wished they could bend down to hear.