T

Sweet Jesus does everything.

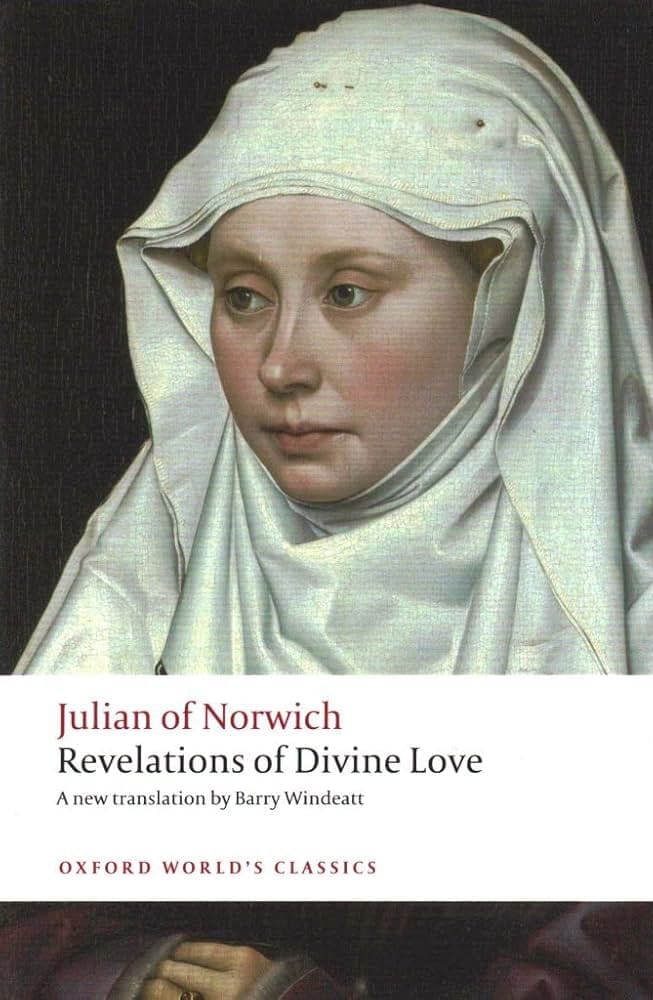

—Julian of Norwich

There are upsides to going to a college where students aren’t allowed to drink. It means that on a Friday night, fun-thirsty youth deprived of their keg parties instead pile into a lecture hall for a true rager: duelling perspectives on the theology of the fourteenth-century mystic Julian of Norwich offered by two Midwestern philosophy professors. On this recent occasion, my colleague Adam Wood made a case that Julian could be squared with Thomas Aquinas. My colleague Ryan Kemp, on the other hand, gave a more existential, Kierkegaardian approach to the anchoress (since published in his elegant book of essays). Both were brilliant, and both were right, because Julian’s writing is capacious enough to allow for both interpretations, and then some. About one hundred students showed up, as well as people from the community. It was hard to find a seat. Keg-party hangovers typically last a day, but all of us who attended this intoxicating evening are still thinking about it months later. I’m thinking especially about Julian’s perspective on unmerited grace.

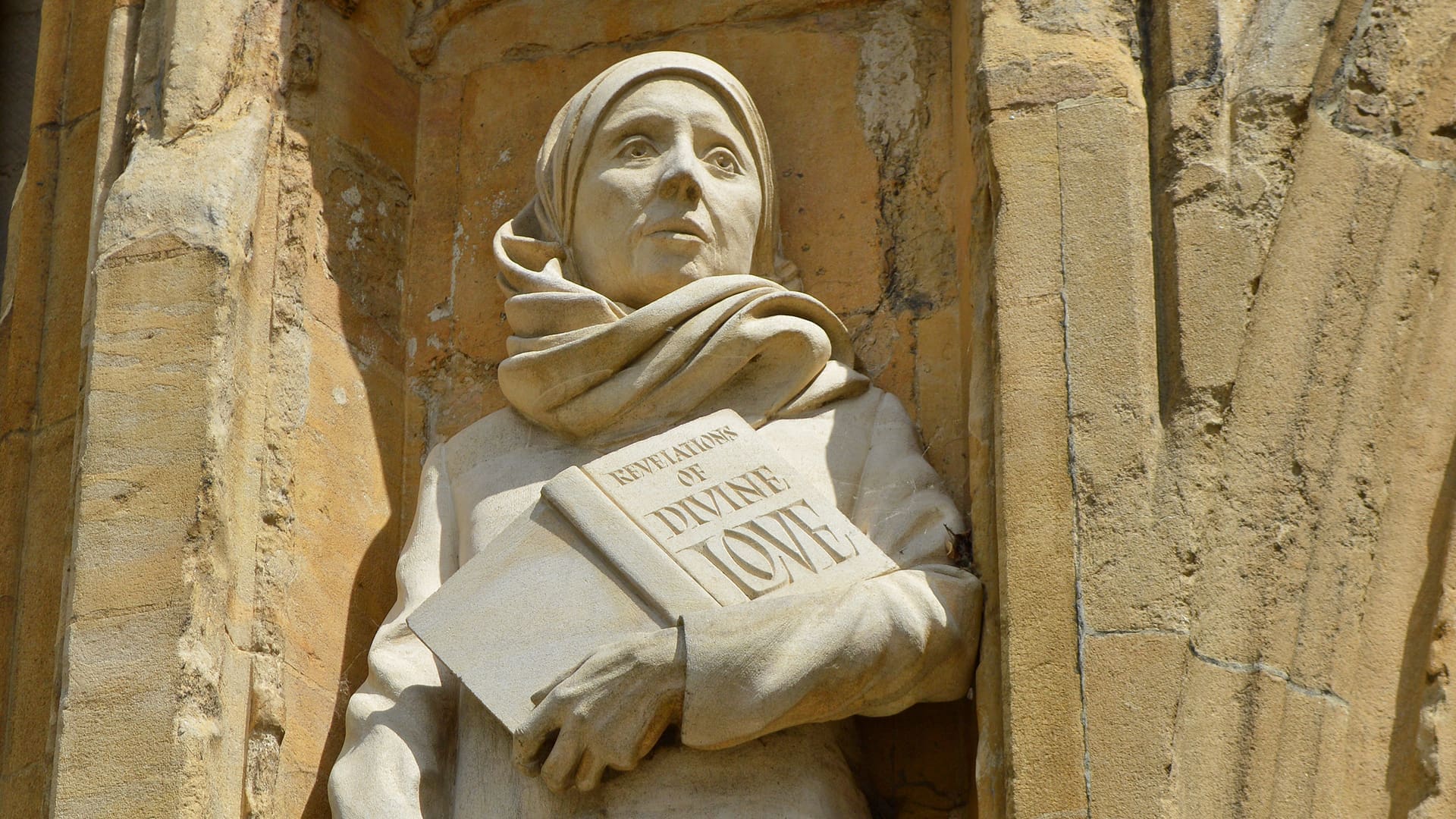

And so, with a conference to attend in London, I decide to honour my colleagues, and Julian, by making a pilgrimage to Norwich. I’ve already made my case for Julian’s evangelical credentials, but it was time to visit what is left of her one-time home. Bombed by Germans in 1942, Julian’s anchorage—a place of seclusion appended to a small church—was reconstructed in the 1950s over the very spot in which she was once sealed. The site now hosts a Julian Centre and a place to stay the night. I’m no tourist, you understand, but a pilgrim.

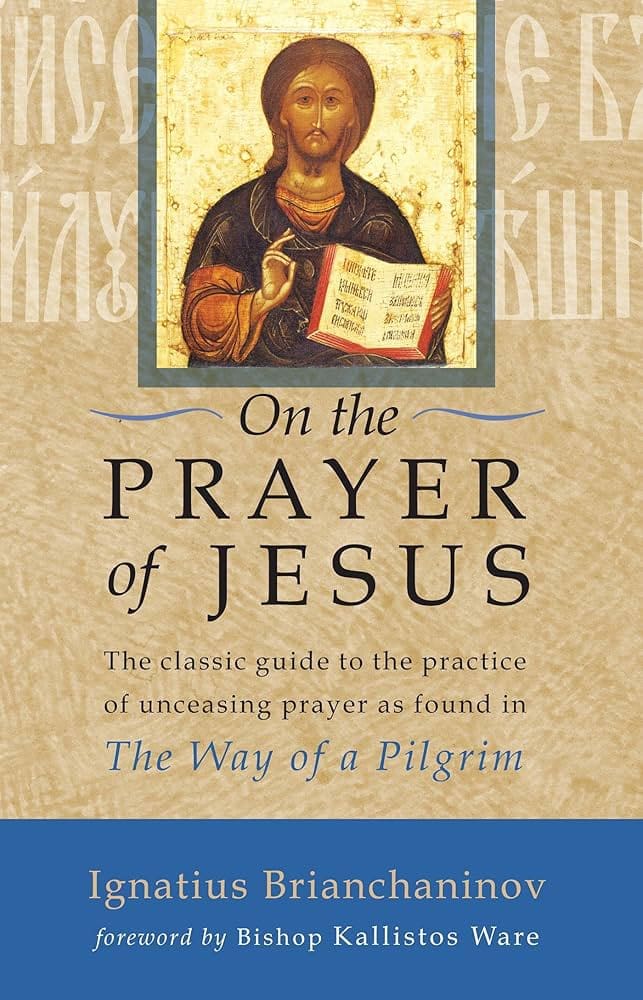

My plane reading is not plain reading but a book by Russian bishop Ignatius Brianchaninov (1807–1867), his famous On the Prayer of Jesus. I am wondering whether this practice is a good way of living Julian’s luminously hopeful theology. And I am wondering whether it is possible to undertake Jesus Prayer devotion while still an Anglican or whether a move to the Orthodox tradition is required. I am surprised to learn in the book’s endnotes that William Palmer, then an Anglican deacon, visited the famous Bishop Brianchaninov in Russia. Kallistos Ware even reports in his introduction that Palmer was allowed to serve during the Orthodox liturgy behind the iconostasis. Even so, the Russians were singularly unimpressed with Palmer’s “branch theory” of the church, in which he argued for the legitimacy of the Church of England. Alas. It seems Palmer himself was ultimately unimpressed by it too, as he eventually followed his friend John Henry Newman into the Roman Catholic Church.

I arrive in Heathrow and make my way to London, noticing that the train downtown passes the “Poor Man’s Walsingham,” the Marian shrine of Willesden, where Catholics and Anglicans have both attempted to restore England to appropriate levels of Marian devotion. We’ve covered this topic in these pages before, but I left one question out: Isn’t the easiest answer to this Catholic-Protestant confessional stalemate simply the purity and provenance of the Orthodox Church? Having spent my professional life studying Byzantine icons, it’s a question I’ve often asked myself.

Waiting for my next train in central London, I switch Jesus Prayer books. This one was penned by “a Monk of the Eastern Church,” whom we now know was Archimandrite Lev Gillet (1893–1980). If there was (or is?) any hope for Anglican–Orthodox rapprochement, Gillet represented it. As chaplain of St. Basil’s house in Notting Hill, he wrote for Sobornost, the journal of the Society of St. Sergius and St. Alban, an Anglican-Orthodox experiment in unity. Ware (who also wrote the introduction to this book) reports that Lev was a true “urban hermit of London, with the great metropolis as his desert.” He showed a “fixed aversion for all forms of ecclesiastical aggression and polemics.” The Jesus Prayer enabled him to walk the city while “recognizing and silently adoring Jesus imprisoned in the sinner, in the criminal, in the prostitute.”

Archimandrite Gillet was even able to “convert” from Roman Catholicism to Orthodoxy without a formal rite of reception, so as not to cast aspersion on the Roman Catholic tradition he came from. But he was also evangelical, literally speaking, for Ware reports that “in the Scriptural meditation of his later years, it was not about Christian Russia that he spoke, nor yet about the Fathers, but simply about Jesus Christ in the Gospels.” Generously honouring the movement of the Spirit among Pentecostals and Protestants, he offered a “universality without relativism” that is difficult to achieve in practice. I am surprised to see in the book that Gillet commends the Anglican mystic Evelyn Underhill, whom he must have known personally, for advancing Jesus Prayer devotion. But Gillet does offer a caveat that Underhill learned the Jesus Prayer from the Orthodox.

By this point I am on the train to Norwich and notice I am passing near the Monastery of John the Baptist, a major outpost of Orthodox devotion in England, founded in the 1950s by a disciple of the legendary St. Sophrony the Athonite (1896–1993). If there is any beachhead for the benign Orthodox invasion of England, this is it. The question emerges anew: Do I really want to satisfy myself with Evelyn Underhill’s late admiration for Orthodoxy when I could have the real thing?

Do I really want to satisfy myself with Evelyn Underhill’s late admiration for Orthodoxy when I could have the real thing?

I arrive in Norwich and head straight to Julian’s shrine. There I see competing icons for sale. One offers a modern interpretation of Julian’s vision of the hazelnut that represents “all that is made” being ever sustained “because God loves it.” The image’s dark and edgy design seems to encapsulate my colleague’s bracing Kierkegaardian interpretation. A more traditional icon of Julian bearing a scroll fits my other colleague’s Thomist take. Next are the conspicuously feline Norwich icons, which might represent those who project onto Julian any manner of modern concerns. Medieval texts do indeed say that cats were permitted by anchoresses—but still, grumbling about how sentimental cat iconography has infiltrated Julian imagery is a mainstay complaint from more traditional voices.

But among these visual options for St. Julian, one of them stands out for its demanding serenity. I read the claim that this image, even if made by an Anglican, “follows the Byzantine Canons” and boasts “no cosy cat.” I purchase the book that accompanies the image, which was penned by British Orthodox converts. I head to a nearby pub and find the book goes well with a pint of beer both less fizzy and cold than I’m used to.

In the preface, Sheila Upjohn says she thought Christianity was just a “two horse race: Catholics and Protestants.” But Orthodoxy, a late discovery in her experience, has now won the derby. Another of the book’s authors, John-Michael Mountney, was an Anglican for most of his life—even serving as rector at St. Julian’s shrine and founding the Julian Centre—until he converted to Orthodoxy. It is a wonderful book, beautifully syncing Julian’s wisdom to Orthodox iconography, almost as if the first identifiable woman to write in English were a Russian, a Serb, or a Greek. Another contributor boasts that English saints like Fursey and Withburga are included in his Orthodox parish’s iconostasis, a move reminiscent of star players of a losing football club being recruited to a team that can actually win. Even so, I am delighted in this book to read how Julian offsets the severity of some Orthodox desert asceticism. As we deepen in prayer, “the only effort we have to make,” these Julian-inspired Orthodox writers insist, “is not to make an effort!”

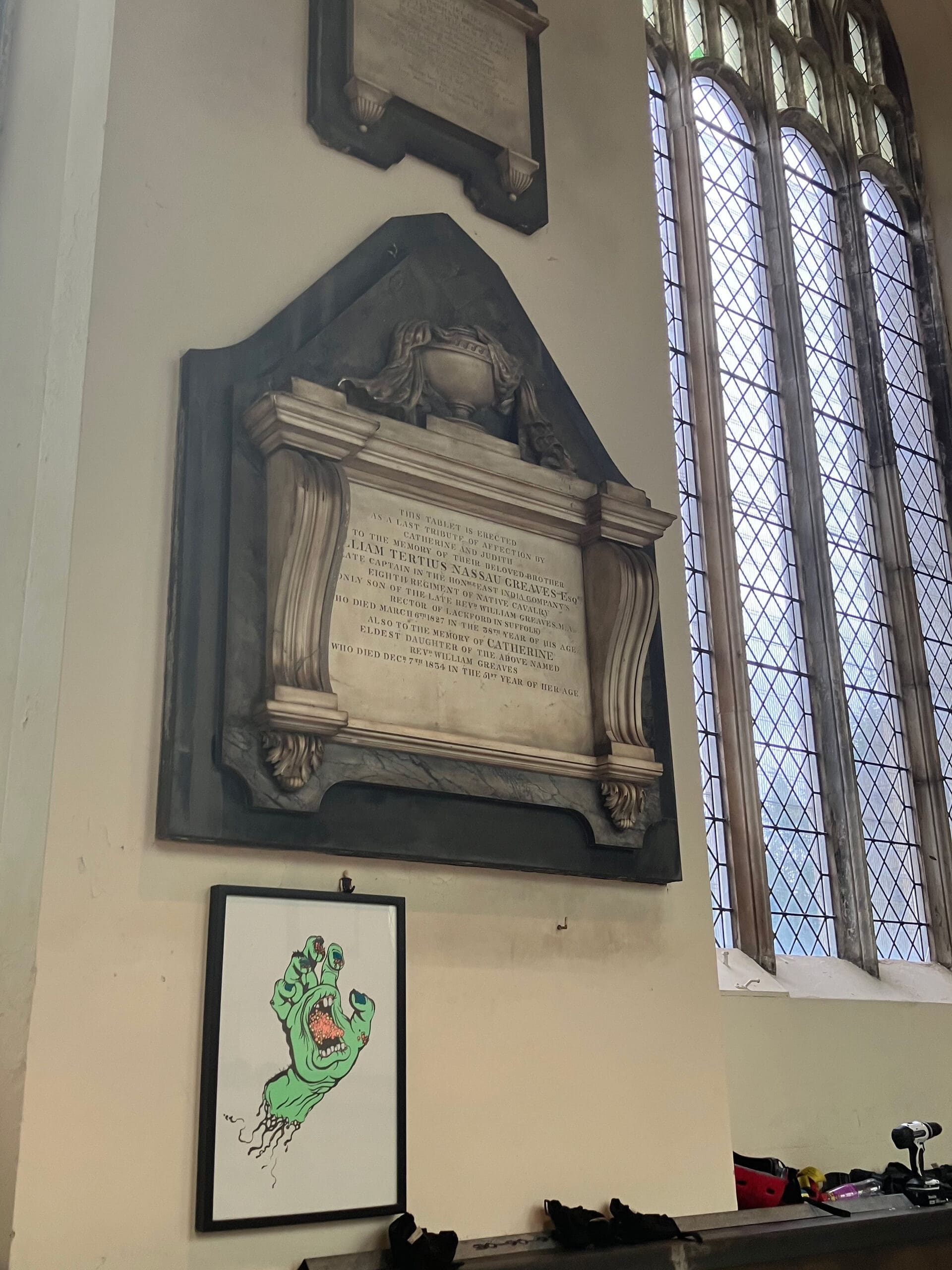

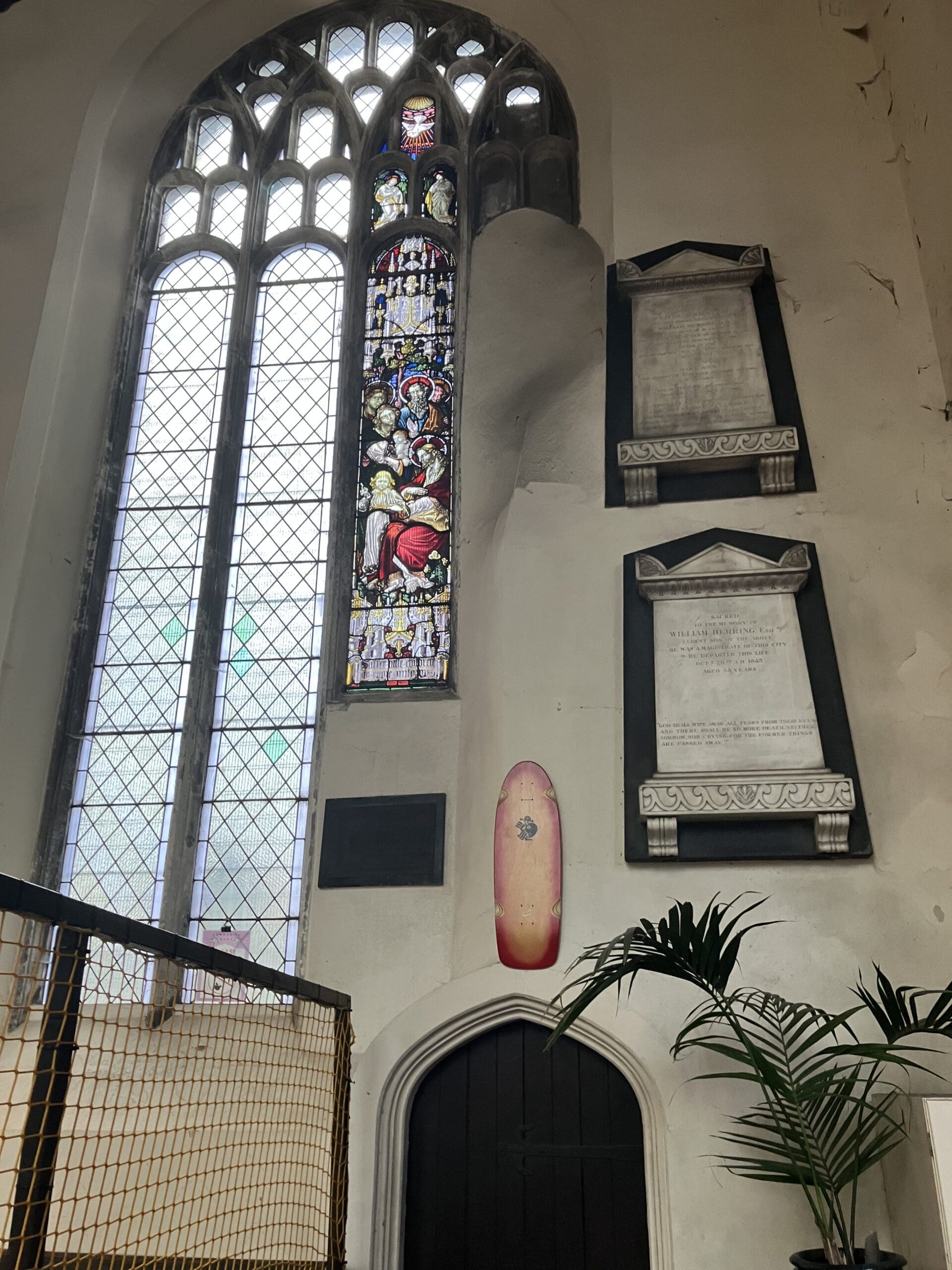

I take to the streets to see more of this town and make my way to a beautiful fifteenth-century church that beckons from the skyline. A sign at the door advertises a skate park. I figure it must be referring to a skate park around the corner, but I don’t see anything around the corner. So I push open the door of the church and hear the sound of skateboards coming from within. The proprietor, about my age but with O-ring piercings and neck tattoos licking his whiskery chin, welcomes me in. He sees the poorly concealed shock on my face and walks me through what I’m about to experience.

“It was once said,” he tells me in a thick Norfolk accent, leaning back while strumming his acoustic guitar, “that in Norwich there was a church for every Sunday and a pub for every day of the week.” But now evidently one of those churches is a skate park, which he presides over with relaxed confidence. Two boys, about the age of my ten-year-old son, ears also pierced with O-rings, but not yet equally tattooed, interrupt us. “You from America?” one of them asks me. When my eyes betray recognition, they erupt into fist pumps of triumph and then skate back to the half-pipe, gliding with youthful nonchalance by the stained-glass windows.

While the former nave is for skateboarding, the choir is a lounging area where tattered leather couches and skateboard magazines line the walls next to what is left of a colourful window depicting the ministry of Christ. The proprietor apologizes to me that the main window is Victorian, but he does brag that a few of the carvings, on which skateboards are now affixed for decoration, are indeed medieval. One of the skateboards even has Orthodox iconography of the Nativity grafted into its design. Skateboard logos and magazines are juxtaposed with effigy burials and plaques to remember the dead in prayer. The roll of wheels has replaced the rhythms of worship, and I am starting to understand why so many people ride the pipeline into Orthodoxy.

The proprietor, perhaps to ease my shock, tells me that another nearby church has been converted to artist studios. I make my way there, and though the studios are closed, through the window I can see the well-used art spaces crowding the choir. I spot a carved gargoyle on the exterior and then see a massive papier-mâché head of a devil placed in an exterior doorway, as if to amplify the gargoyle. Like the Satan imagery at the former church of the Holy Communion in New York, which is now an exercise parlour, the move feels like a deliberate affront.

As you might expect, I’m unsettled. I head back to my room in the shrine guest quarters. There I keep reading the Julian-was-really-Orthodox book, but I notice an unexpected shift toward the end. The book may have begun by boasting about the three-hundred-million-strong Orthodox communion, but by the end comes a concession that more than a third of that communion is out of communion with itself. Fortunately, the authors saw a need to distance themselves from the corruptions of Russian Orthodoxy and the war it has recently sponsored.

This reminds me of other recent writing from converts to Orthodoxy, such as this painstakingly documented claim: “It cannot be doubted that the institution of the Russian Church and many of its clergy, indeed the totality of its native episcopate, are participants in the war and enflame it with apocalyptic rhetoric.” Or an equally harrowing account titled “Waving Farewell to Byzantium”: “I was a barely-Orthodox fawn in the headlights of my own stupid protest against Protestantism at the time,” laments one convert after delineating the staggering crimes of Moscow. All such accounts remind me of Gillet’s “fixed aversion for all forms of ecclesiastical aggression and polemics.”

But this mental adjustment on its own is inadequate. I need saintly counsel. Outside the window of the shrine guest house, a hazelnut bush recalls the anchoress’s most famous words. Realizing my room is named after one of the visitors who came to Julian of Norwich for guidance, Margery Kempe, I follow suit. That is to say, I too go to Julian for guidance, but alas I must go to her via the translation of the Showings I picked up in the gift shop.

Why does God allow such awful corruption? Julian answers:

Really, Julian? Skate-park Anglicanism and Russian priests blessing nuclear warheads are okay with you?

So all you’re leaving me with really is your tired maxim “All manner of things shall be well”? It’s been so degraded by overuse that the last word could instead be “swell.”

Julian interrupts me, insisting that I not quote her out of context, limiting her wisdom to a saying that fits on a souvenir mug:

Okay, Lady Julian, but why can’t I know more of that now?

I reply to Julian that this all seems dangerously close to condoning sin. I don’t want to offer a pass to the erosion of the Church of England or Russian neo-imperialism. Her tone then grows severe:

But, Lady Julian, I can at least be angry about it, can’t I? I am angry about moribund Anglicanism captive to fading ideologies, and I am angry about militarized Orthodoxy (not to mention militarized Protestantism).

But is it not okay to expect more from the Holy Church to which you so constantly appeal?

As I keep reading, Julian shifts my focus from the crimes of Christendom—things done (“holy” war) and left undone (the surrender of sacred space)—to prayer.

With this comes my next revelation, which is not so much an intellectual eureka as it is a sad discovery. Why in my litany of complaints, fogged by the thick mist Julian accurately describes, did I not just stop and pray for Russian Orthodoxy, that the voices for peace within it would prevail? Why did I almost enjoy the shock of the skate park instead of praying for the kids within it, whom Christ looks on so tenderly just as he does in the images of him gathering the children in the remaining stained glass?

Over breakfast the next morning, I get something of an answer for the skate park. Josiah—the young Anglican medievalist who tends the guest quarter at Julian’s shrine—explains to me about the situation in Norwich. He concedes with a grimace that the devil sculpture might have been intentional, and that the skate park was quite a scandal in Norwich when that unfortunate decision was made. But he also tells me that Norwich was once the wealthiest city in England next to London. Its wealth came from sheep in the surrounding countryside that had been won back from the sea. Norwich in its heyday of wealth kept building churches. When attractive new ones were constructed, citizens abandoned the old ones and left them empty. At the city’s height there were sixty-four churches, more than one for every Sunday of the year.

That the Church of England can’t keep up with this scale is understandable, but that is not the whole story. Fortunately, the cathedral in Norwich did not make the short-sighted move of selling its surrounding properties as did so many other cathedrals, a move that so reduced their revenues that some are forced to charge admission or rely on increasingly elaborate public-relations stunts. The Norwich Cathedral, Josiah explains to me, is relatively strong. There are two places where the Church of England is growing, he explains: Anglo-Catholicism and evangelicalism. But wherever the church succumbs to political activism, he tells me, it stops growing. “They might be right,” he offers with a skeptical smile, “but they sure don’t grow.”

I then head to the Sunday service at the Julian church next to the anchorage, which is comfortably full. I guess this is what one of the growing churches looks like. A young Anglo-Catholic priest preaches with a combination of fervour and precision. He exudes the same joy and peace written about by Julian seven centuries ago just a few feet away. He celebrates the Eucharist with efficient reverence. He announces that an Anglican representative to the Orthodox Church in Romania is set to give a series of talks and retreats on the beauty and spirituality of Orthodox icons. He will, however, do so as an Anglican.

Putting all this together, I conclude that perhaps Julian of Norwich does not “belong” to any of the churches. Instead, she was ahead of and above us all, pulling each of us together into a theology that is bigger than our divided communions.

Perhaps Julian of Norwich does not “belong” to any of the churches. Instead, she was ahead of and above us all, pulling each of us together into a theology that is bigger than our divided communions.

What could be more Catholic than her loving focus on the crucifix and blood-caked wounds of Christ, or her insistence on obedience to Holy Church? What could be more Orthodox than her tender and visual devotion radiant with coruscating hope of resurrection? She even has her deluxe, expanded version of the Jesus Prayer.

But Julian’s capaciousness does not stop there. Often Protestants are politely ignored in ecumenical convergences. It is assumed the only contribution we can make is to generate more skate parks. But what could be more reminiscent of the Lutheran doctrine of imputation—in which Christ’s righteousness is imputed to us—than Julian’s claim that “our Father neither can nor will attribute any more blame to us than to his own son, beloved Christ”; or, “He makes no distinction in love between the blessed soul of Christ and the least soul that will be saved”; or, “Christ alone performed all the works concerning our salvation, and none but he, and just so he alone is at work now on his final purpose”?

Is there a better encapsulation of Luther’s doctrine of simul iustus et peccator (at once justified and a sinner) than the statement “In the sight of God we do not fall, and in our own view we do not remain standing, and both of these are true”? Wildly enough, Julian even articulates the Protestant insistence that sanctification (“We ought to rejoice greatly that God dwells in our soul”) be secondary to justification (“and we ought to rejoice much more greatly that our soul dwells in God”). Like it or not, Julian offers a classic encapsulation of the very theology of liberating grace that was infused by Thomas Cranmer into the Anglican Book of Common Prayer.

Here Catholic or Orthodox Christians might protest that I’m picking and choosing only her more Protestant-sounding sayings, for Julian also says, “Beware that you do not select one thing according to your inclination and preference and overlook another, for that is what heretics are like.” But is the gospel of unmerited grace what Julian had in mind as “heresy”? Were the Orthodox “heretical” when they fulminated, a full millennium before Luther, not with 95, but with 226 theses against “those who think they are made righteous by works”? Is the curious confluence of Orthodoxy and Protestantism, lately expounded on quite eloquently by both Eastern and Lutheran writers, just a dismissible quirk?

Why God allows our continued divisions I do not know. Julian may well have wondered which of the three contemporary popes she should have chosen, for much of her life was during the Great Western Schism. Faced as we are with the scandalizing absurdity of our church divisions, Julian tells us, “It is fitting for the royal lordship of God to keep his counsels undisturbed, and it is fitting for his servant, out of obedience and respect, not to wish to know his counsels.”

Still, we can wonder something. Perhaps if the churches were unified, then Putin would have a more difficult time drafting Russian Orthodoxy to bolster his war. Perhaps the churches in Norwich would be flourishing enough to reconsecrate the skate park, maybe building a proper one so kids could practice their ollies after church in a universe seamed together by more than brands like Vans, Antihero, and Thrasher.

My hope, though, is not in distant prospects of future unity, exciting as those may be, but in the gospel of grace without which any such unity would be in vain. “The blessed comfort which I saw,” writes Julian, “is bountiful enough for us all.” Julian’s anticipation of the Anglican emphasis on grace, for me at least, is a peculiar summons to abide within Anglicanism. The best move, therefore, may be not to. Julian, sealed into her anchor-hold for the remainder of her lifetime, certainly modelled that. “In him we are enclosed,” from those confines she thundered, “and he in us.”