H

How do you define luxury?

For those whose heads don’t turn at the passing of a Maserati or who don’t have a clue which fashion designers are really breaking the mold this year, answering this question might seem like an irrelevant intellectual exercise. Middle-class North Americans, though wealthy by global standards, don’t typically consider their income level as one that grants access to luxury. And for those of us who consider ourselves followers of an itinerant first-century prophet, this question might make us squirm with holy fear and haul out our chequebooks to add another zero to our tithe.

But hang on: someone cares how each one of us defines luxury deep down inside, whether we profess to care or not. So maybe the question is worth pondering a little more deeply.

Luxury loves you

Even if we don’t think of luxury as desirable or relevant, we each seek enjoyment beyond life’s perceived necessities and make decisions about what kinds of enjoyment we will pursue, and where, and in what quantities, and for what price. In a global economy that functions on a sustained exchange of resources, predicting the behaviours that drive these decisions is a big deal.

According to Dr. G. Clotaire Rapaille in the 2004 ad industry documentary The Persuaders, corporations will pay hundreds of thousands of dollars (and more) to “crack the code” on the human desire for luxury in order to sell ever more products and services. Executives flock to Rapaille’s mansion to learn how the good doctor has used his psychiatric background with mute autistic children to understand consumers’ unarticulated, “reptilian” impulses. These executives have stuff to sell, and not just to the wealthiest 1% of the population—to you.

The notion of someone seeking to manipulate our subconscious impulses makes most of us uncomfortable. We don’t want to acknowledge that we’re not in control of our desires, particularly when it comes to the vast array of luxury items being marketed to us—including everyday “luxuries,” like the latest mountain-scented, ultra-concentrated, super-brightening, extra-fluffing laundry detergent. Seeing through consumer-targeted messages is a starting point for approaching luxury with Christian discernment, but it’s only a beginning, particularly when the subsequent response is an overly simplistic rejection of luxury in its entirety. From the latest interior decorating magazines to the biblical narrative, luxury is a much more complicated subject than it might first appear.

The “new” luxury

In her November 2008 editorial for the now-defunct Domino magazine, Deborah Needleman laid claim to the publication’s definition of “the new luxury.” Needleman writes, “If the old definition of luxury relied on status symbols like of-the-moment handbags and private planes, ours celebrates experiences—being more instead of having more, or caring less about what others think and more about just what makes us happy.”

Over the next two pages, some of the staff picks for personal luxuries attempt to bear out Needleman’s distinction: “swimming in the ocean. . .fresh flowers. . .an entire day where I have nothing to do. . .humor. . .not being in a rush.” An accompanying photograph features the editor with her children in their garden. For those who want to see magazines like Domino as guardians of a happiness that defies the capacity of one’s chequebook, the evidence is there—but so is just enough proof to maintain a hold on diehard, brand-loyal materialists.

Embedded among ads for metallic ottomans and Vera Wang china are other personal luxury staff picks like Globe-Trotter luggage, a Cartier Love bracelet, D. Porthault linens (“so decadent”), and a George Smith sofa. “Not to worry, we still adore objects!” Needleman writes. “But today’s luxury goods aren’t just products—they’re cultural artifacts.” In part, she’s making space for the Domino-reading demographic that still ascribes to an older, brand-driven definition of luxury, but she also makes a profoundly true statement about things: an object always represents more than its tangible self. It represents ideas. It’s a symbol of its designer’s and consumer’s deepest beliefs about who we are as human beings, what our purpose is, where we’re going. For example, a Cartier love bracelet is a piece of jewelry that belies a certain belief about the tenacity of romantic relationships. Like to the chastity belts that husbands once fastened to their wives’ waists to ensure fidelity, a love bracelet is affixed to the wrist using a tiny screwdriver kept safe by one’s lover, implying all sorts of assumptions about gender relationships and human nature.

Feminist criticism aside, an expensive bracelet can bespeak an appropriate longing for loving commitment. Marriage itself is a costly relational luxury and there’s a reason we symbolize it through the exchange of precious gems and metals, rather than plastic baubles from a vending machine. A critique of Domino‘s definition of luxury that delineates bad tangibles from good intangibles is insufficient; there’s something good about objects and the commitments they symbolize. But does a commitment to an intangible good inherently validate the tangible object, even when it’s a $7,000 bracelet? What does appropriate luxury look like, if it even exists? And is there such a thing as appropriate luxury that encompasses concrete objects as well as intangible experiences like “not being in a rush?” If a magazine like Domino picks at the seams of these issues, the biblical narrative mercifully unravels and reassembles them.

An extravagant narrative

“Extravagant” is a word that often gets linked with “luxury,” denoting something that is “extra” or beyond what is necessary. However, a contemporary praise song by Casting Crowns makes me wonder about reclaiming this word in light of the biblical narrative. “Your love is extravagant,” the song goes. “Spread wide in the arms of Christ, there’s a love that covers sin. No greater love have I ever known.” This song is not great poetry, but it does deserve credit for using a loaded term in a fresh way. In connecting extravagance with God’s good and overflowing abundance, it raises the stakes for an exploration of luxury within the biblical narrative.

Whether or not it is embodied in his or her lifestyle, the first ideological tendency of many Christians is to associate luxury exclusively with material goods and dismiss it as too “worldly.” Within a dualist theological framework, spirit is good and matter is evil, so we’re better off locking luxury in a closet clearly labeled SIN. In other words, extravagant love is fine, but expensive perfume is not.

Few of us actually live out this dualism to its fullest extent. Instead, we tend to consider the status quo neutral, accommodating our standards of material “necessity” to a dominant culture, even while our worship and confessional language denigrate the material world.

However, it’s simply not possible—or desirable—to reject all that we can experience with our five senses in favour of some sort of pure, spiritual reality. After all, what could such a reality possibly consist of for creatures who were made from and for this earth, and this earth for us? In Mere Christianity, C.S. Lewis writes, “God never meant man to be a purely spiritual creature. That is why He uses material things like bread and wine to put the new life into us. We may think this rather crude and unspiritual. God does not: He invented eating. He likes matter. He invented it.” Christians who affirm the created goodness of bodies and matter, as well as God’s use of the physical as a form of communication, will need to wrestle a bit more with the concept of luxury. We simply don’t have the option of being anti-matter, because we are matter, created out of earth and charged with being loving stewards of all that is seen. And “what is seen” in the God-breathed world sets the standard for extravagant beauty, as anyone who’s ever photographed a sunset or marveled at the striking beauty of a flower knows.

As human beings made in the image of God, we seek to approximate divine creativity in our architecture, in our food, in our music. Our offerings may be imperfect, but our inclinations to create exist by design. In addition to the divinely spoken creation of a good and beautiful world, there are instances of luxury throughout the biblical narrative that affirm not just the handiwork of God in the creation of the earth, but the appropriate extravagance of certain expressions of human culture. Throughout the story of the Israelites, we witness the skilled craftsmanship and rare treasures that go into the creation of the tabernacle, and then the temple. Only the best work and materials were suitable for the most holy of places as symbols of reverence and worship.

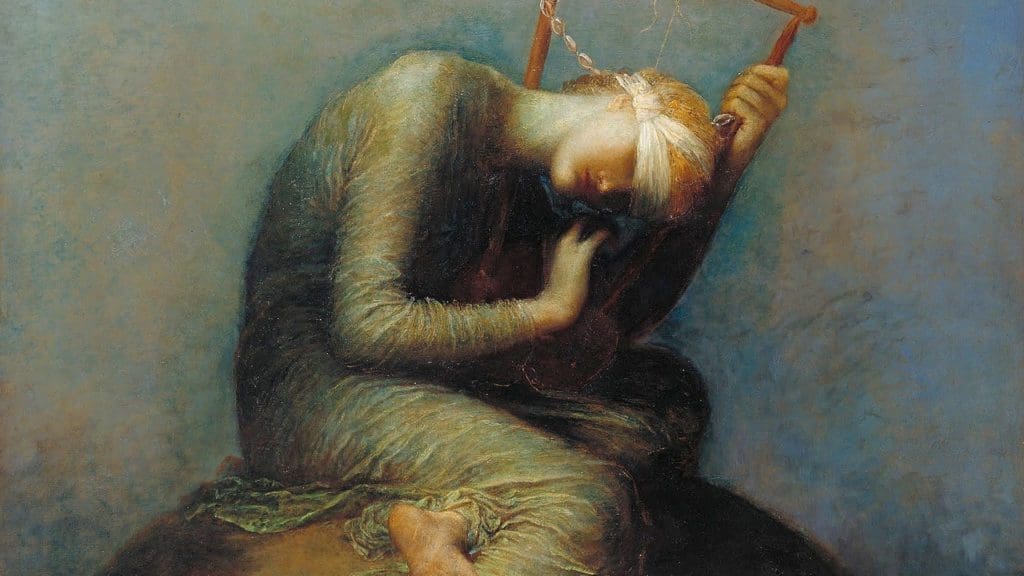

Centuries later, we get to overhear Judas rebuking Mary for pouring expensive perfume on the feet of God-in-the-flesh. Subsequently, Jesus rebukes Judas: “Leave her alone. She bought it so that she might keep it for the day of my burial. You always have the poor with you, but you do not always have me.” Lest we underestimate the extravagance of Mary’s act, Debbie Blue reminds us in her book Sensual Orthodoxy,

Imagine a pound of perfume. It’s hard to imagine because all you ever see is an ounce or two or maybe five, but never a pound . . . It’s really an impossibly enormous amount of perfume. It’s not even luxurious, it’s comic. It’s so exaggerated, it’s nearly obscene.

Apparently it was worth what would be a decent year’s wages. Imagine thirty thousand dollars of perfume poured out at once in an enclosed space (actually while people were trying to eat dinner). This is beyond lavish. This is unreasonable. This is not a rational act.

In the face of apparent irrationality, Judas spoke what every reasonable person in the room must have been thinking. However, as Blue points out, “it’s interesting that it’s put into the mouth of Judas, the betrayer, made into a lie.” So if Judas is a parsimonious liar and Mary gets it, does this story simply baptize our indulgence in everything from a game of golf to $2,000 platform heels if we can finagle a justification in Jesus’ name?

A luxurious present

We learn a lot about our purposes in the world and the character of God when we place ourselves in the historical context of the biblical narrative. Cultivating a Christian approach to luxury also requires placing ourselves honestly in a contemporary global context. Implied in the Domino staff’s elevation of simple pleasures as luxuries is a normalizing of the cultural access enjoyed by those who have enough. The luxury of “a cleaned-out closet” implies having a home and enough stuff to fill—indeed clutter—a closet. The chosen luxury of “good coffee” implies an economic status that allows for coffee makers and $4 lattes—things most coffee growers can’t afford. If there’s a biblical precedent for loving matter and embracing extravagance while we live in a world with so much need, what are we left with, beyond a neurotic awareness that flings us constantly between pleasure and guilt?

Fortunately, we’re not condemned to the whiplash of a pendulum when we accept an alternate paradigm of paradoxical centredness modeled for us by God and by the people of God. In a 2007 lecture, author and theologian Lauren Winner refers to contemporary echoes of Judas’ question related to the perceived extravagance of investing in the arts:

It seems to me to not be a very faithful question to ask, “Oh, how come you as a Christian aren’t devoting all of your energy to ameliorating poverty?” At least it is not a question that is forged in the idiom of a God of abundance. We live in a secular world governed by a capitalist model of scarcity. There’s never enough money in our world. There’s never enough time. All of our resources are scarce. But by contrast, our God gives us a very different economy. Our God is a God of overflowing creative fecundity; a God of inexhaustible Eucharistic offering; a God, after all, who multiplies loaves and fishes. So, to borrow Marva Dawn’s phrase, one of the things that marks us as followers of that God is the consistent practice of being royally wasteful, of wasting time by praying and worshipping, an activity that by the world’s standards is at least unproductive, and maybe psychotic. We might all be standing in a room talking to ourselves. Christians need not, because of our God of abundance, always be concerned about the evident utility of everything that we do. We are instead called to worship and reverence a God who is a God interested in whimsy and not just utility.

The possibility of a “royally wasteful” economy suggests that there may be a difference between holy and unholy luxury. Holy luxury is not just a convenient means of Christianizing material success defined by whatever dominant culture is currently passing through; such a lifestyle is characterized by competition and isolation. By contrast, holy luxury bears fruit in gestures of extravagant generosity that are borne on branches shaped by God’s abundance and rooted in love. The story of Mary’s offering is particularly striking in its absurd subversion of cultural norms. Her act was a complete mystery and even a lewd offense to those who couldn’t read the foreshadowing of death or the depth of grateful love in her sacrifice. In any social context, whether the poverty of nomadic first-century evangelists or the mansion of a corporate executive, royal wastefulness will often seem ridiculous and irresponsible.

Jim Forest, a Catholic worker colleague of Dorothy Day beginning in 1961, was one of many who was instructed and sometimes confused by Day’s example of whimsical abundance. In “What I learned about justice from Dorothy Day,” he writes:

Tom Cornell tells the story of a donor coming into the Catholic Worker and giving Dorothy a diamond ring. Dorothy thanked her for it and put it in her pocket. Later a rather demented lady came in, one of the more irritating regulars at the house. Dorothy took the diamond ring out of her pocket and gave it to the woman. Someone on the staff said to Dorothy, “Wouldn’t it have been better if we took the ring to the diamond exchange, sold it, and paid that woman’s rent for a year?” Dorothy replied that the woman had her dignity and could do what she liked with the ring. She could sell it for rent money or take a trip to the Bahamas. Or she could enjoy wearing a diamond ring on her hand like the woman who gave it away. “Do you suppose,” Dorothy asked, “that God created diamonds only for the rich?”

The paradigm Day attempted to live into was characterized by discerning what to hold tightly and what to hold loosely. As Cornell’s story illustrates, she held loosely to the ownership of objects and to prevailing ideas about wise allocation of resources. At the same time, she held tightly to the image of God in all people and to the goodness of a Creator who buried gorgeous stones deep in the earth not just for the delight of the kind and rich, but also the annoying and poor. At their best, actions like giving someone a diamond ring can be rooted in a deep love for God and others.

Renewed desires

Though he comes off as eerily serpentine in The Persuaders, Dr. Rapaille demonstrates keen understanding when he analyzes the “reptilian” self as a means of understanding our deepest desires. The choices we make are motivated by a complex matrix of factors, at the center of which are core desires that we can’t always fully articulate. Where Dr. Rapaille’s vision breaks down, however, is in his low view of humans’ ability to shape their desires beyond animal instinct through formational disciplines. Trapped in a castle paid for by marketing firms, Dr. Rapaille doesn’t seem to fathom the existence of a mystical way of life that could significantly alter the reptilian impulse.

Disciples of Christ experience the Holy Spirit’s transformation via the rituals of love-oriented communities seeking to embody the Kingdom on earth as it is in heaven. While the humans in the doctor’s world are as predictable as lab animals, the humans in God’s world are beloved friends worthy of self-sacrifice, invited into the renewal of all things tangible and intangible, seen and unseen.

In the process of rejecting the identity to which Rapaille would confine us and accepting our identity as the beloved of Christ, Christians must learn to surrender to the more expansive reality of divine love. Debbie Blue writes,

What if being a disciple is an authentic response to being loved[?] And what if being loved. . .actually feels like being loved[?] Not like some abstract belief we adhere to, not like something so-called-purely-spiritual, as if there could be such a thing, but something that has to do with the part of us that thirsts and hungers and feels and suffers and loves and cries, our passions, our needs, what is thoroughly and essentially human in us . . . God’s love is that connected to what we need, to our guts, to our passion, to our essential humanness.

In this context, cracking the code on luxury might ultimately be an effort toward understanding God’s extravagant love for the world and how we might respond to such love. Solid matter that we are, we are still see-through creatures to the Creator, a reality that is alternately comforting and terrifying. On the one hand, it means that greed with a thin veil of generosity can only fool our fellow finite friends. On the other hand, gestures such as Mary’s, so embarrassing in their excess and ostensibly flawed in their reasoning, are not met with rebuke. Rather, we are met in our vulnerability with even greater passion by a God so extravagant that even time, universally restrictive to humans of all economic means, does not present a limitation.

“Luxury” is a term that will continue to be used to sell tangible things and intangible ideas, while “extravagant” will continue to be a derisive assessment of perceived excess. However, in a deeper understanding of the goodness of matter and the Holy-Spirited formation of desires, there’s liberation from market-driven manipulation and short-sighted reasoning that concedes too much to the status quo of the moment. Modeling the whimsy of Dorothy Day or the royal wastefulness of Mary may not unlock a path that leads to a bed bedecked in D. Porthault linens, but it can open up a way of life that deepens a shared experience of our present humanity while prophetically proclaiming the coming Kingdom.