E

Everyone knows about Adolf Hitler. Most know something of Benito Mussolini. But few even remember the name of Gabriele D’Annunzio.

Yet before much of the world was swept into the death spiral of the Second World War, the blueprint for a new world order was being crudely sketched by this eccentric Italian poet. Born in 1863 amid the violence and nationalist rhetoric of Italian unification, D’Annunzio was to become the “greatest writer in Italy since Dante.” Well, at least according to himself. Yes, he was that kind of man. Recovering greatness—literarily, nationalistically, delusionally—marked his life.

We Don’t Talk About D’Annunzio

An enthusiastic reader of Nietzsche, D’Annunzio grew enamoured of reviving the suppressed Dionysian elements of the lost Greco-Roman world: frenzy, excess, libido. The Apollonian restraints that had privileged mind and soul over the body and its appetites were, in D’Annunzio’s rendering, forces of emasculation. So he began to form his life as an Übermensch. He confronted the challenge of his existence boldly: flying some of the first planes, fighting bravely in the Great War, experimenting with drugs, sticking his nose up at outmoded institutions like monogamous marriage and monarchy. His greatest feat, though, came in 1919 when, at fifty-six years old, he led thousands of jaded Italian veterans to annex Fiume, a former Italian port city that had been given to the Slavic Croatians after the Treaty of Versailles. (Just imagine Oscar Wilde leading a successful military campaign that would see the English flag planted in Brittany and you get an inkling of how absurd all this was.)

Under D’Annunzio’s short-lived rule, Fiume became a harbinger of things to come in Western Europe. From the balcony of his villa, the aged writer gave vitriolic speeches about the eroticism of war and Italian superiority. He raised one arm in what was believed to be a lost Roman salute. Crowds of beleaguered Italians mobbed to watch these carefully staged performances, experiencing a deep and frenzied solidarity in the vision D’Annunzio was casting for their future. It was Mussolini, then a strategically detached admirer of his elder compatriot, who would liken the strength of this impassioned mob to the fasces, an old Roman term for a bundle of sticks tied together. The seeds of fascism were germinating in Fiume.

For the ancient Romans, though, fasces were not merely some bucolic symbol of lost rural virtue. Fasces were used to inflict cruel pain. One stick might lance the flesh; a gathered bundle could break bone. Fascism promised solidarity and required brute strength to attain it. In their clearly identifiable “black shirts” and military uniforms, D’Annunzio and his followers began a reign of terror over the non-Italian residents of Fiume. Many Slavic people were forced out of homes, beaten, raped, and tortured with a diabolical ferocity.

Yet Fiume wasn’t only cruelty. D’Annunzio also adopted the Buddhist symbol of harmony—the swastika—as his emblem for this new social order, one in which inherited social values (particularly around sex) could be discarded. In The Pike: Gabriele D’Annunzio—Poet, Seducer, and Preacher of War, Lucy Hughes-Hallett sheds light on a man “whose rampant vanity and sexual desires knew no bounds.” And despite being described by the Parisian courtesan Liane de Pougy as “a frightful gnome with red-rimmed eyes and no eyelashes, no hair, greenish teeth, bad breath, [and] the manners of a mountebank,” D’Annunzio bedded dozens of the most beautiful and celebrated women across Europe. If Italy had been emasculated, it seemed D’Annunzio was hellbent on reasserting a certain form of potent masculinity. Sex was less about status than strength. The poet publicly bragged about the pleasure he found in raping working-class women and, so it was rumoured, even employed “a housekeeper who was expected to have sex with him three times a day.” It was all merely another form of control.

Thousands of young twentysomethings—mostly men—descended on Fiume after its annexation. Self-described “futurists,” these men embraced industrialization and the machine age while glorying in the recovery of Roman power and Roman sexual mores. Homosexuality was decriminalized and openly practiced. Cocaine-fuelled orgies and group sex were normalized by many inside and outside D’Annunzio’s inner ring. Many women—especially Slavic women—fled in fear of rape and forced prostitution. Until the Italian army and navy finally moved in and the “Bloody Christmas” of 1921 brought the “party” to a screeching halt, Fiume was no longer just another port city, but a very odd, discordant poetic symbol. It was the site of gut-wrenching violence and unrestrained sexual license, dictatorial control and decadent carnivale.

Yet male lust and lust for power are often just two fruits of the same branch. And as the twentieth century dawned, it was D’Annunzio who brought into stark relief the ways in which the libido and the libido dominandi would go hand in glove in the brave new world about to emerge in Western Europe and beyond.

Origins and Abundance in the Two Cities

Given D’Annunzio’s desire to reanimate the ghosts of Roman might, it might also be necessary to resurrect Augustine’s framing of Rome in the City of God. The City of Man epitomized in pagan Rome, Augustine argued, is directed by its libido dominandi, while the City of God is directed by love and gives glimpses of the coming Kingdom. But for our purposes, I want to consider what this near-ancient framework might have to say about the way men and women relate to one another in the two cities.

For starters, we need to recognize that both the City of God and the City of Man—by very different means and to very different ends—promise to usher in an abundant life for their respective citizens. This abundance is contingent on a distinct framing of the relationship between men and women. In the City of God, men and women are understood as complementary pairs, gifted to one another in their different bodies, which, in their union, become potentially generative of new life. The world’s abundance, then, images God’s abundance. It is predicated on a unity in diversity that opens up the possibility for the unfolding of more life.

In contrast, the City of Man is predicated on control and requires oppressive hierarchies of the powerful over and against the weak. In this vision, men dominate or rule over women (and others deemed weaker). Of course, in such relationships new life is still generated, but over time the life is only parody—diversity gives way to a controlled sameness. The refrain of the City of Man is not only discordant but also monotonous.

There are many Christian communities with very unhealthy (and unbiblical) visions of men and women that, perhaps unwittingly, follow the logic of the City of Man. Conversely, there are some beautiful glimpses—if we have the eyes to see them—of the City of God in pagan writing and non-Christian communities.

The lines demarcating these figurative “cities” are never easy to determine, particularly for fallen creatures who see dimly. The two cities are never simply the “church” versus the “world.” In this time the church is what Augustine calls a corpus permixtum, a mixed body: these two cities grow alongside each other like wheat and tares, sometimes looking identical. There are many Christian communities with very unhealthy (and unbiblical) visions of men and women that, perhaps unwittingly, follow the logic of the City of Man. This is to be expected in a fallen world. Conversely, there are some beautiful glimpses—if we have the eyes to see them—of the City of God in pagan writing and non-Christian communities.

Cards on the table: I believe the refrain from the City of Man seduces but never satisfies. Its vision of abundant life is illusory. The reason it cannot satisfy is that it is a lie, an idol rather than an icon. It’s not that its vision has no power; the twentieth and twenty-first centuries bear grim witness to its very real potency. No, what I mean is that, ultimately, the vision of life on offer in the City of Man is a deep perversion of what was originally good. And to get to this original goodness, we would do well to attend carefully to origins.

The earliest cosmogonies—stories of cosmic origins crafted in poetic meter, sung or chanted well before they were ever written down—were not just idle entertainment. They were orienting narratives telling men and women where they came from and where they were going, what they were, and, most importantly, why they existed. While these creation myths are all unique, they contain significant overlapping elements and are always gendered in significant ways.

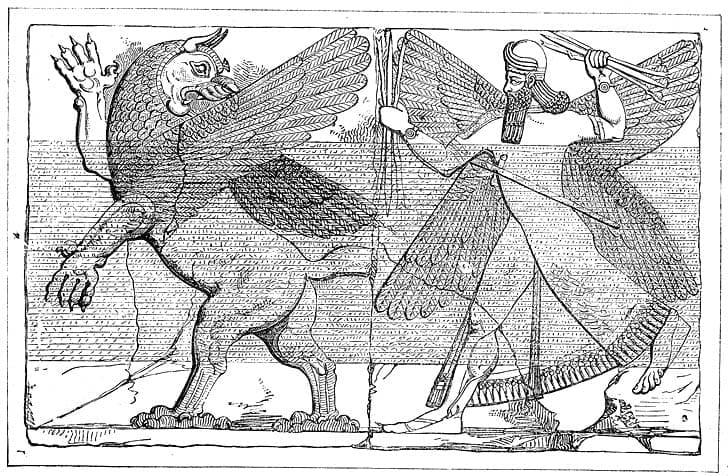

The oldest cosmogony is the Babylonian Enuma Elish. In it we find primordial waters that mix. The River, gendered male, flows into the chaotic Ocean, gendered female and named Tiamat. This mixing creates a frothy soup, a womb from which the gods emerge. Tiamat, worried that space is scarce, starts swallowing up these gods, but the ferocious male god Marduk is undeterred. He fills the gaping mouth of Tiamat with hurricane winds. While she is thus “impregnated” with air and swells, he pierces her body with his lance, killing her. Rending the corpse of the Divine Mother in half, he forms the earth and the heavens. From his own blood mixed with earth, Marduk crafts humans—men and women—to be a race of slaves who will do his bidding.

For the Egyptians, one of several creation stories tells of Nuit, the goddess of the night, being in an erotic embrace with her husband Sibu, the earth god. The god Shu violently separates them, casting Nuit to the heavens, where her contorted body gyrates. Sibu, the male, becomes the fertile land on which animals and humans dwell. The Egyptians had many variations on cosmic origins, but a unifying theme was that the primordial chaos of the waters and the wasteland—manifest in the harsh desert and open sea surrounding the Nile delta’s fertility—had to give way to maat, the principle of order and the origin of life. It is the male sun god Ra who dries up the water with his light and heat. Mounds of earth emerge that are rich in fertile potential. The king, or pharaoh, becomes the human embodiment of Ra on earth and is responsible for its fecundity and abundance.

From Hesiod and Homer we learn that the Greeks, too, start with chaos and night in their cosmogony, but also Erebus, the place of death. Light, Day, and Love drive these away and allow Gaea, mother earth, to appear. Gaea gives birth to the male god Uranus, or the Heavens, who then envelops her in an erotic embrace, creating the cyclops and Titans among other monstrous creatures. Uranus despises and fears his progeny and tries to have them banished. But Gaea and her youngest son, Cronos, successfully ambush Uranus, castrating him and throwing his severed genitals into the sea. From his wounded body new monsters and demigods emerge, but Uranus is exiled. Repeating the pattern of his father, Cronos starts to destroy his children in fear of usurpation, swallowing them whole. Yet he, too, is deceived—the Greeks love their tricksters!—and his youngest son, Zeus, finally overthrows him, ruling Olympus with his lightning bolt, begetting children and fornicating with divine and mortal women through deception, seduction, and sheer power.

Thousands of other stories could be told, but in these some patterns already start to emerge. In each we see a world begotten through separation and division. Order must emerge from the chaos of mixed elements: light from darkness, heaven from earth, sea from soil. This separation is violent and shrouded in conflict. Tiamat’s corpse is torn in two. The gods are human. There is lust, avarice, wrath from the very beginning. We see the obvious connections between the feminine and fertility, the masculine and power. Oppressive forms of hierarchy are evident. Woman as the begetter of life and the receiver of seed is analogous to the womb of the world from which crops and life mysteriously emerge. Man, however, is usually the physically more dominant and the sower of seed. Man is tied to war and domination, the one who procures land for crops and women for progeny. Man, in the image of the gods, asserts himself and takes action before action is taken against him.

Death was always a haunting neighbour. An uncontrolled drought or flood or infertility quickly reminded ancient men and women that they were at the mercy of the gods, manifested in the invisible forces of the physical world. For this reason fertility rites were an intrinsic part of ancient pagan societies. The immortals were capricious, to be sure, but perhaps there was a way for mere mortals to control them.

This control of immortals was tied to the sexual practice of mortals. In the Mesopotamian region, cults for Ba’al and Asherah required elaborate sacrificial systems where the blood of bulls and sheep were tied to divine blessing. In crises such as prolonged droughts, Ba’al even required child sacrifice and the slaying of firstborn children. Asherah, the goddess of fertility, could be manipulated through ritual group sex. In a form of sympathetic magic, the goddess could be controlled by the transgressive—that is, non-marital—coupling of humans. Temple prostitution abounded.

When the Greeks displaced the Mesopotamian religions, the fertility cults merely took on different gods. Asherah was replaced by Artemis. And in Corinth, for example, there were over one thousand prostitutes in the temple of Aphrodite—goddess of love—to manipulate the growing conditions necessary for life. On the male side, worshippers of Pan undertook Dionysian festivities—the very ones D’Annunzio and Nietzsche believed should be resurrected—that involved drunkenness and orgies to maintain the favourable disposition of the gods.

There was undoubtedly an “abundant” world in ancient empires like Babylon, Egypt, and Greece, but this abundance (as is the case with every misdirected vision) is only abundance for some. For many women, many vulnerable, and many outsiders, a world where abundance is tied to the exertion of a largely masculine lust for power is both terrifying and dangerous.

We know in hindsight that the germination of that tare called fascism came to full growth under the Nazi regime. And we know that under Hitler’s control, vast swaths of land were gobbled up to “make room” for the Aryan race. Jews, ethnic minorities, the weak and infirm, the disabled, and others were murdered to allow this perverse vision of abundance to unfold. In the world fashioned by the Nazis, the circle of acceptable difference was vanishingly narrow. Only Aryans should procreate. All ethnic and ideological others had to be sterilized or eliminated. Hierarchy. Control. Sameness.

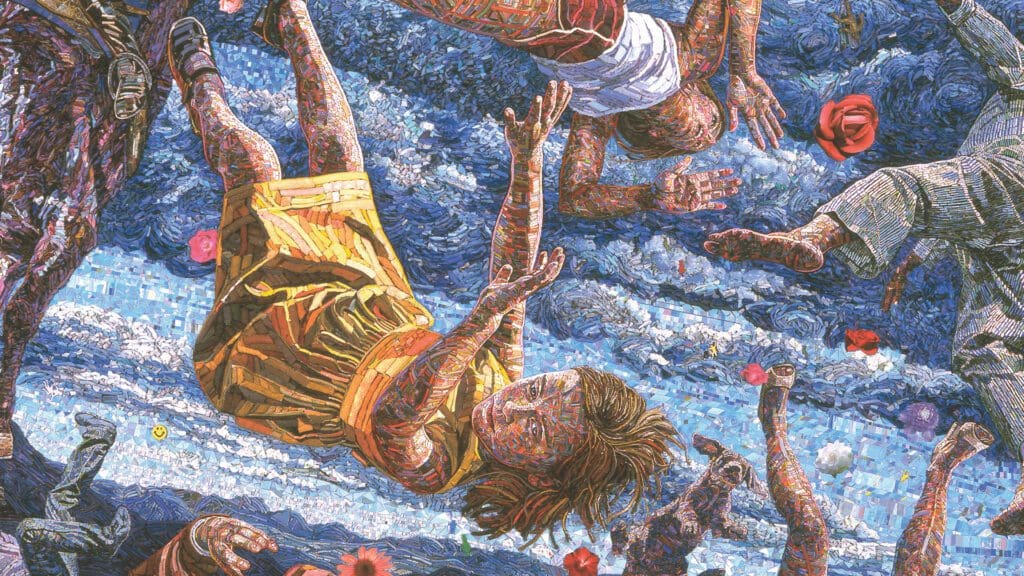

D’Annunzio’s playbook was studied by Hitler, who then perfected it in ways that still haunt us. But Neil Postman argues that liberal societies naively imagine an unbridgeable abyss between themselves and such despotic nations only because they have forgotten that they, too, easily become oppressors in a culture that worships different false gods: those of an unrestrained and tainted “pursuit of happiness.” The rise of sex slavery and exploitation of young women in our Pornhub culture and the increasing cases of young teen women irreversibly “undoing” their female bodies are well documented. These are enacted not despite liberalism but in its very name. In the name of unrestrained freedom, hierarchy, control, and sameness simply take on new form.

Perhaps the nymphs have departed from our disenchanted, techno-industrialized imaginations. Sacrificing rams, let alone our children, seems impossibly barbaric to our “advanced” sensibilities. But the fertility of both the earth and the female body is still something we seek to control. In a world of GMOs and birth control, we achieve by different means the abundance of life every ancient civilization sought. Like our superstitious ancestors, we are still very much in the business of exerting control over the uncontrollable. And this perverse abundance, just like the ancients’, comes at a terrible—even sacrificial—cost to many.

In the twenty-first century, the City of Man still sings its discordant song.

Relinquishing Control in God’s Theatre

The biblical cosmogony of Genesis is not created from scratch but deeply connected, indebted, and responsive to the cosmogonies of the ancient civilizations of the Near East. Some of the similarities are quite obvious: order from chaos; a masculine God calling forth life out of a fertile earth; even the repeated focus on separation and division of heaven and earth, day and night, land and sea.

Yet, as Abigail Favale notes in The Genesis of Gender, Genesis “could not be more different” from the ancient creation accounts, Babylon’s in particular. The key difference is that “creation is intentional and orderly—a light flickering in the dark. God doesn’t create through violence and death, but through language; he speaks the world into being.” Favale unpacks the Genesis account in more detail—and really, you should read her excellent book—but one aspect that continues to intrigue me in the book of Genesis and throughout the Christian Scripture is not merely the telos of humanity’s complementary, gendered division but also the means by which God brings this division about.

In ancient cosmologies, gendered differentiation is framed among the gods and subsequently among humans as a site of conflict and power play. The gods are made in the image of man, something early Christians and even philosophers like Plato really did not like. It is no wonder, as Tom Holland shows in Dominion, that the contours of Greco-Roman sexual ethics were primarily about power rather than love, to say nothing of service. For a healthy male to be in a submissive sexual role was far more of a taboo than was adultery or homosexuality or polygamy. Honour depended on who played which role. And “role play” is significant in a pagan world rendered as the theatre of man’s glory. In such a world—in such a City—power and bloodline rule.

The amplification of the world’s abundance is not just an idea but a material reality that unfolds in time.

In Genesis, however, a different vision subtly emerges. The world God declares “good” on each day is good both in itself and in potentia. God delights in a world teeming with diverse species and kinds, but it’s only just getting started. The amplification of the world’s abundance is not just an idea but a material reality that unfolds in time. In Scripture, Culture, and Agriculture, Ellen Davis remarks that even the Hebrew attention to “seed-bearing plants” reveals a “self-perpetuating fruitfulness that must have served to counter the religious ideologies of Israel’s pagan neighbors.” According to Davis, this debunked the myth not only that the earth’s fertility was due to the insemination of the earth by Ba’al but also that men and women were slaves created to produce food and offspring for the gods’ consumption. In Genesis there is already good news that the reverse is true: “the Creator of heaven and earth is the generous One who provides.” This is a recurring theme in the City of God’s ongoing symphony.

The world’s abundance is self-perpetuating, but that means it still unfolds in and through and by the flesh of people and animals and plants. New species will emerge; new peoples will cover the face of the earth over millennia. The differentiation of male and female sexes in plant, animal, and human life becomes the means by which the possibility for a teeming and diversified world is realized. Just look around: the profusion of life seems a miraculous impossibility. Yet this is the world we inhabit, one in which, to use Rowan Williams’s language, there is an almost impossible “moreness” around every corner. And this abundance is the abundance wrought through procreation. In all the separation and division taking place in the Genesis account, male and female kinds are given one to another in order that something new might be given to the world.

When God “mandates” ’adam—the earth creature—to “be fruitful, and multiply, and fill the earth,” it is a command with futurity built into it. Yet this creature has no suitable mate. In fact, Robert Alter notes in his wonderfully annotated translation of the Hebrew Bible that some readings of Genesis 2 even suggest the ’adam is possibly an unsexed creature until the ’adamah—or woman—is created. We know, at least, that no language is spoken until this female partner is made for communion and communication. This is not hierarchy but deep interdependence.

But where does this ’adamah—different from ’adam yet equally an image bearer of the Creator—come from?

We learn that God forms the woman from the “rib,” which is importantly also an architectural word, tselah, since God is going to “build” the woman. Something more, though, is still lost in translation. The connotations in Hebrew suggest that God did not just pluck a rib as one might the wishbone during Thanksgiving dinner. Rather, God quite literally rends the ’adam in two, splitting him in halves from which two new creatures are generated. It is mitosis on a human scale. While he performs this, the Genesis poet tells us, God puts the ’adam into tardemah, a deep sleep. Pope John Paul II provocatively calls this a “sleep of nonbeing,” from which the first creature is taken out of existence in order that two new creatures can awaken into new life.

If the self-perpetuation of the world were not enough, man’s complete lack of power in the face of procreation should put to rest any illusion that abundance in this world is attributable to human control or a Nietzschean or Roman will to power. The ’adam cannot generate the ’adamah needed for their mutual companionship and the society that would emerge from their descendants. He must receive the gift in gratitude, remembering that the world’s abundance, like the world’s existence, does not depend on him at all.

It might seem that in the fallen world some effort is now required. The punishments for our rebellion mean that both birth and agrarian work—the respective labours of women and men—are now strenuous and painful. But in Genesis 15, when God establishes his covenant with Abram, the word tardemah, that sleep of nonbeing, intriguingly reappears. And we get another glimpse of the countercultural thread around gender and abundance that God is weaving into the story of his relationship with his rebellious, forgetful creatures.

In the passage, Abram is required to cut a series of five creatures, from a bull down to a pigeon, right in half. Alter notes that “cutting a covenant” this way was common in the Near East and meant that the party who failed to hold up their bargain would end up severed like the animals they walked through. Yet when the time comes to walk through, God puts Abram in a deep sleep. God walks through alone. This covenant was God’s promise to the elderly Abram that he would give him land and progeny, a promise that seemed increasingly illusory to the aged, infertile, homeless nomad. Yet God shows that even in his fallen Kingdom, this is the way of abundance. If Abram trusted that God would make his progeny like the stars of the night sky and the sand on the seashore, then he had to relinquish control. He, too, must enter that sleep of nonbeing and awake to a new life. In a few years from this moment, Sarai’s “dried-up womb” becomes fertile. The gift of Isaac is on its way.

This theme again emerges subtly but beautifully in the New Testament as Christ prepares his bride, his beloved, who will mysteriously become his agent of abundance and life to the entire fallen world. Before the second ’adam went to the cross to have his body broken, he went into the garden to pray. It was in Gethsemane that Jesus prepared to take the final steps that would reunite man to the Creator. A path to new life and abundance was being sketched out, but right up to the last minute Jesus’s closest disciples still hoped the new world order Jesus promised might come through that age-old exertion of power—against the Romans, against the religious establishment. They wanted hierarchy and control. But Jesus had another play—Christians too, I think, should love their tricksters. Jesus would relinquish power. He would not control but serve. He would not take life—as every false god wants—but give his up, freely. With bloody sweat, he would pray, “Not my will,” and completely deny himself.

And where were the disciples, those bold advocates of power and domination, as Jesus struggled in the garden the night before his crucifixion? They were in a deep sleep, just like ’adam, just like Abram. They were passive, able only to receive the gift they were about to be given. And like the ’adamah, it is the church as bride who will emerge from the side of the second ’adam, rent on the cross.

This is the mysterious path to abundance in a world that is always, despite how easily we forget, the theatre of God’s glory. And in this theatre, oppressive hierarchies of control give way to self-sacrificial agape love. To be a man and to be a woman in imitation of Christ is to lay down one’s life in the service of others and relinquish the heart’s natural bent for libido dominandi. Just as the ’adam needed the ’adamah, we as God’s riven creatures need relationships with one another on the horizontal plane alongside relationships to our Creator and Bridegroom on the vertical plane. And because of this vertical dimension, marriage and friendship are only ever penultimate goods. Single, widowed, or childless men and women are all capable of finding their fullest human identity by being in relationship to the Creator who calls them his beloved. Children to a Father, bride to a Groom.

On that night before he died, when Christ took the Passover bread and broke it and pronounced that this was now his body, he ushered in an entirely new form of the old covenant. He turned Passover into the Lord’s Supper, a meal of runaway slaves into a wedding banquet. Some of his disciples, watching their rabbi break the bread and pour the wine, might have thought back to the bloody rending of the animals in Genesis 15. Many of them were likely reminded of the breaking of loaves that, in Christ’s earthly ministry, fed so many thousands with leftovers to spare.

But I also wonder if any of them watching the Logos made flesh saw traces of their ancient origins, in which this their Creator, now with hands of flesh and in their presence, divided the bread into two just as he had, so long ago, divided the heavens from the earth, the sea from the dry land, the day from the night, the ’adam from the ’adamah—and in that division, miraculously, did not diminish creation but unleashed its “moreness.” Did the disciples glimpse this? I don’t know.

Christ revealed the path to abundance that requires renunciation of our natural inclination to dominate. He invited us to see how we can die to self in order to live.

But it is clear that Christ showed us—or recovered for us—a form of greatness, a form of being men and women that amplifies God’s glory in unique, diverse, life-giving ways. He revealed the path to abundance that requires renunciation of our natural inclination to dominate. He invited us to see how we can die to self in order to live. How we can give up control and even let go of the desire for the illusion we have control and thus receive the gift of our bodies for one another and for him. Each night we fall to sleep should be a creaturely reminder of the gifted grace we need to receive for each day. Each morning a reawakening into the abundance of existence we did not—could not—generate.

It is told that Hitler, near the end of his life, rarely slept. He was so paranoid someone would take his life that he required cocktails of drugs just to control the elusive gift of sleep. He stayed awake usually past four in the morning, surrounded by an increasingly narrow inner ring of people who looked, acted, thought just like him. In his final act, the man who had orchestrated the elimination of millions of men, women, and children was unable to receive his death but took it with a cyanide pill.

Many of Christ’s first disciples would go on to die violent deaths as martyrs under Rome’s cruel strength. Men and women, husbands and wives and children, would be burned, thrown to animals, persecuted, killed. Yet in their martyrdom the early church would learn the cruciform path to new life and the costly road of abundance. In their final moments, when death stole upon them—as it will for all of us—I wonder if they, too, felt that they were just partaking in one last “sleep of nonbeing” in the sure hope of awaking, like ’adam, like Abram, to the new life gifted by the generous One who miraculously multiplies by division. And more than this, waking to a final reunion with the Groom they—we—have been separated from since the garden.