H

Humans touch animal bodies every day. We digest their flesh. We clothe ourselves with their skins. We sleep on their feathers. We listen to music made by sliding animal hair across animal intestines. We swallow extracts from their organs and tissues as medicines and smear them on our faces and hair as cosmetics. Few of us ever see these animals alive, much less see them as they die. Few of us want to. Just the thought evokes a gut-rumble of disgust.

What does that disgust signal? Is disgust the voice of some primordial conscience telling us to all become vegan? Or is something more complicated happening at the cultural and even spiritual level? Are there ways we could interact with animal bodies that foster greater love and honour for animals, humans, and God?

I began facing these questions with urgency when our family purchased our first four wriggling, curly tailed, newly weaned pigs. As stewards of a two-and-a-half-acre property in southern Wisconsin, we had come to terms with the fact that our clay soil, lack of tractor, and abundance of walnut trees all pointed to one farming option: pigs. Besides, we liked the idea of turning weeds into bacon.

We live on the fringe a large city, so most people who visit us have never met a pig face-to-snout. When they realize that these creatures we call by name will become food in a matter of months, their reactions range from curiosity to horror. How can you scratch those cuties behind the ears, oversee their deaths, and then pull pieces of their bodies from the freezer to eat on an ordinary weeknight? How can you make sense of that?

On our first butchering day, I watched pig blood seep into the soil, and I had no good answer to these questions. One thought overwhelmed me: There should be a ritual for this. Here were creatures passing from life to death and onward to become sustenance for other creatures. It felt sacred. But my people—white, semi-urban, Midwestern Protestants—had lost whatever memories we once carried of how to mark that sacredness.

Most days my work is not farming. I am an anthropologist by training, which means I use interviews and participant observation to study the ways people make meaning in life. And so I decided to put my two vocations together. My farming experience became a springboard to research the ways other farmers, hunters, chefs, and butchers handle that strange liminal passage between caring for animals and eating their flesh. I focused on people in my surrounding Wisconsin farmlands who identified with the ethical meat movement—a system of people aiming to raise and process animals in ways that minimize animal suffering, enable natural behaviour like rooting and breeding, preserve heritage breeds, treat labourers justly, and maintain ecological sustainability. I visited farms, attended conferences, analyzed influencers’ media, took a butchering class, and butchered my own animals.

I quickly discovered that I was not alone in desiring a sacred ritual when my animals died. What struck me most about the ways these farmers and meat processors ushered animals from life to death was how reverent they were. One farmer said eating was “the most religious thing I do every day.” Another said beginning to raise and harvest his own meat “opened the floodgates to a complete existential crisis.” In her memoir, Killing It, Camas Davis describes what she learned from French artisan butchers and along her journey to found a culinary school in Portland, Oregon. She says butchering made her “feel a part of something bigger, something full of respect and, yes, maybe even sacred.” Even people who denied having any religious faith told me they whispered “a little non-religious thank-you prayer” as their animals died, or that farming taught them a “religion” of “gratitude, thankfulness, and awareness.” I began noticing spontaneous prayers around animal deaths everywhere. As contestants on the television show Alone compete to be the longest survivor in the Arctic, they nearly always utter a prayer of thanks to God, universe, or animals as they capture fish, squirrel, grouse, and moose. Something about partaking in the momentous crossover between animal death and human life seems to ineluctably arouse worship.

Something about partaking in the momentous crossover between animal death and human life seems to ineluctably arouse worship.

Living in rural communities in South Africa and Nicaragua in my twenties and thirties, I met entire communities of people who, unlike the community that raised me, shared communal rituals for killing meat animals. In South Africa I attended funerals and weddings where killing a cow or a goat commemorated the unity across families living and dead. On a recent visit to the Nicaraguan village where I once lived, I experienced again how animals were central to communal life there as well. Slaughtering days were rare and cause for celebration. Neighbours arrived before dawn to help with the exhausting work of capturing, killing, hanging, eviscerating, shaving, skinning, and butchering. The animal would be familiar to everyone in the village—piglets are tied outside homes where they can be fed from kitchen scraps, and larger hogs forage in the surrounding forest. By early light, a crowd of gleeful children gathered, each carrying a fistful of cash and a bowl to take home portions for their families. Boys sharpened knives and grasped hooves while men hacked apart larger bones with machetes. Even young girls washed blood from tables and weighed meat portions for sale. Without refrigeration in the village, everything would be sold and cooked in the next twenty-four hours. And nobody—not even children—expressed anything like disgust. As for most humans across history and the planet, the rarity of meat and the necessity of community to procure it compels these families to receive it with gratitude, wonder, and joy.

There was a time when my own European ancestors wove rituals and prayers for meat animals into everyday life as well. A 1952 European Catholic prayer book is packed with prayers for agricultural life. The book includes blessings for herds, bees, pastures, and stables, and a memorable prayer for lard or bacon with instructions to sprinkle the meat with holy water: “Lord, bless this creature, lard, and let it be a healthful food for mankind.” By the end of the twentieth century, prayers for meat animals had all but disappeared from liturgical life in European and American Christianity. A Presbyterian prayer book published in 2012 includes prayers for the death of a pet and the sudden loss of a farm animal but makes no mention of animals killed intentionally for human consumption. As one Midwesterner told me, “I have never seen anything Christian focused on slaughter anywhere in any context. Wow. Wow. That alone is a little disturbing.”

“Lord, bless this creature, lard, and let it be a healthful food for mankind.”

The disappearance of meat animals from liturgical life occurred concurrently with the processes of industrialization and urbanization that swept meat animals out of sight and mind. Through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, enclosures, refrigeration, railways, genetic seed innovations, confined animal feeding operations (CAFOs), massive meat-packing plants, and corporate conglomerations dramatically reshaped the way humans interact with food. Cheaper meat prices made possible by fertilizers and farm subsidies, along with national advertising campaigns, spurred not just a new way of producing meat but new ways of consuming meat as well. The number of animals killed for meat in the world increased nearly ninefold in the second half of the twentieth century.

Decisions about meat became untethered from local communities and their ethics. Whereas the amount of meat a family consumed long depended on the capacity of the surrounding ecology to sustain and mutually be sustained by animals, meat became a commodity exchanged for money passed from stranger to stranger. People learned to treat meat as just another de-moralized object, useful for generating profits in a world where “business is business.”

And yet meat is not just another object. Meat comes of life. That life is endowed with dignity by a Creator. Deep down, we know this, and it stings. Food psychologist Hal Herzog points out, “As our consumption of animal flesh has increased, so has the guilt, shame, and disgust we feel about the way we treat the animals we eat.” Eating meat catches humans in what psychologist Steve Loughnan dubbed the “meat paradox”: people simultaneously dislike hurting animals and like eating meat.

The most common way the industrialized world deals with the meat paradox is willful ignorance. In 1978, anthropologist Marshall Sahlins noticed that the more closely North Americans associated an animal or meat cut with human life, the less they valued it. Cuts with non-human names like “steak” or “porkchop” were preferred over cuts with names evoking human bodies, like “heart” or “liver.” This dualistic logic determined prices and reinforced class hierarchies. Lower-class people, who ate cheaper cuts because of their affordability, became associated with “disgusting” meats, as well as with the underpaid and dangerous “disgusting” jobs in the meat industry. Most Americans would rather not think about the damage this system does to soil, animals, labourers, and climate.

But ignorance is not the only option. One option is to slow the system by reducing or eliminating meat from one individual’s diet after another. While that option can, when multiplied across a lifetime or society, markedly decrease some of the harm done by the industrial meat complex, it does not answer the troubling question of what would become of entire species of animals that can survive only in domestication. Pigs left to long lifespans can develop intimidating tusks and grow as heavy as cows. Chickens bred for meat consumption die of heart failure brought on by weight gain within weeks after their scheduled lifespans. Whether we eat them or not, these animals exist, and deciding how to ethically care for them is not as simple as washing our hands of eating them.

Another option is what I call re-enchanting meat—a way of interacting with meat that recovers dignity and sacredness within the relationships between animals, humans, and also their Creator. Max Weber noted at the turn of the twentieth century that Western industrialization accompanied what he called disenchantment. Modern humans came to believe that they had limitless powers to know, control, and market their universe, and with that belief came a view of the universe as devoid of mystery, wonder, spirituality, and creaturely interdependencies. And yet, as sociologist Richard Jenkins writes, disenchantment has always been “subverted and undermined by a diverse array of oppositional (re)enchantments.” In other words, people keep figuring out how to find the sacred. Even, in this case, in the meat on their plates.

For Christians, re-enchanting meat begins with remembering that all food comes from a gracious and generous God. The first time an animal dies to support human life in the Bible, the animal is killed not by humans but by God. Adam and Eve had sinned and discovered their nakedness, so God replaced their feeble fig-leaf coverings with garments of animal skin. This minute act foreshadows the ram killed in Isaac’s place, the lambs killed at Passover, and all the doves, goats, and cattle killed in the ceremonial life of Hebrew people. For ancient Israelites, the fragrance of fire-seared meat was a daily reminder of mortality, sacrifice, and gratitude. Ultimately, God’s first animal sacrifice to cover Adam and Eve’s sin points to Jesus, the lamb of God, sacrificed to cover the sin of all humanity.

Theologian Norman Wirzba notes that food is, by definition, that which human bodies need but cannot produce in their own bodies. Food is the quintessential daily opportunity to practice gratitude for God and all creation. In a 2008 essay Wirzba writes, “However much we might think of ourselves as postagricultural beings or disembodied minds, the fact of the matter is that we are inextricably tied to the land through our bodies.” These ties are “of immense theological significance because what is at issue is our separation from the ways of God at work.”

What rituals and practices might we revitalize or invent to re-enchant our relationships with God, each other, and the creatures that sustain our lives? How might we turn eating into a reminder of God’s grace and our inter-creaturely dependency? Here the farmers, butchers, and chefs I studied offered a plethora of starting points.

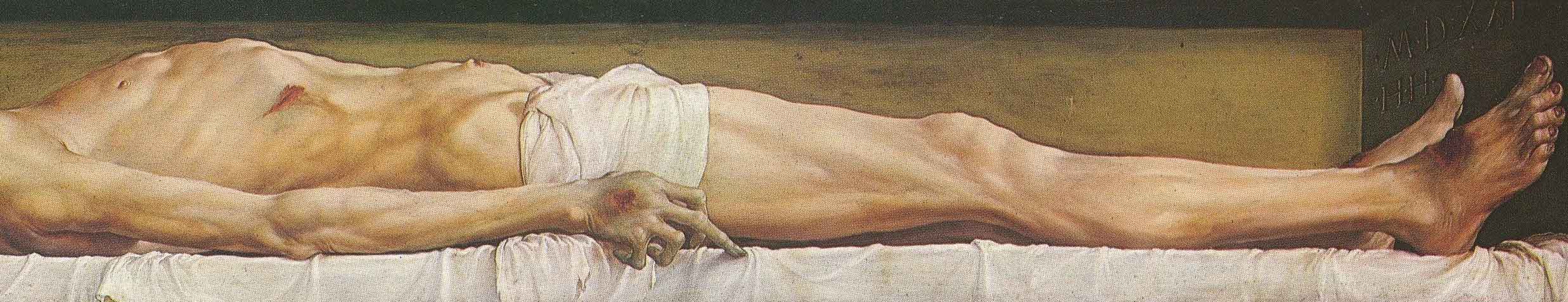

First, we can allow meat to become an entry into the spiritual practice called memento mori—remembering our mortality. People who work closely with meat animals often point out that knowing where meat comes from is not just about facing an animal’s death; it’s about facing one’s shared creaturely mortality. Seeing meat animals up close can be a step toward facing and overcoming latent fears of death. Davis writes about an epiphany she had as she held animal organs. “Pig brain. My brain. Pig tongue. My tongue. Pig skull. My skull. For some people, pressing like against like, as I was doing, standing there with a dead pig’s brain in my hand, inspires revulsion. But instead I felt kinship. Reverence. Wonderment. Trepidation. And melancholy. At once.” Bartlett Durand, one of the butchers I interviewed, similarly explained that the shared mortality of humans, animals, and all living creatures is central to his work. He said he founded his company, Conscious Carnivore, on the belief that “we’re part of an ecology. For life, you kill. There’s really not a way around it.” A sign at the entrance of his meat shop reads, “Eat like we’re all connected.”

Rather than evade the reality of impending death, Christians face death with a fearlessness rooted in Christ’s power. We are, as the psalmist reminds us, mortal like the grass that withers. We are children of Adam, whose name echoes the Hebrew word for the soil to which our bodies will return, adamah. But as the apostle Paul writes, the promise of eternal life to Christ followers means death has lost its sting. To live out that belief, Christians might do well to learn from farmers who face death in their own animals.

One farmer, a Christian, said she put a lot of thought into deciding to raise and eventually harvest her own animals. “I prayed when I did it. I spent a little time with them, you know, sort of with my hands on them, thanking them—not even out loud or having a big ritual, but just pausing to think about it. And I realized, who wouldn’t want to die such a noble death that they’re feeding other people? So I don’t feel bad about slaughtering animals to eat. I feel bad about anything that is thoughtless in farming.”

Another hog farmer said the first time she raised animals, she couldn’t watch them die. Soon after, she changed her mind. Now she considers it essential to be aware of and responsible for her animals from life through death. “I am making this choice for this animal, so I should see it killed. I should see it hanging, dripping; I should be part of it. We all should be part of it if we’re going to eat meat.” She believes humans “need to be in touch with the death part.” She tells customers not to be disgusted by or afraid of meat from the animals they have met. “You are what you eat, and you loved that animal. You need to eat the love you put into that animal.”

For this farmer and others I met, reverence around animals was not just about an ethereal spirituality. It was tied directly to behavioural choices that restore material wellness to people, animals, and the planet. One such practical choice is to let nothing go to waste. I visited one butcher shop where employees actively educate consumers to try lesser-known recipes with heart, tongue, and liver, as well as broths, sausages, and dog treats that make use of every last bit of meat. Not only does this wasteless approach help small farmers earn a living wage; it is, as one butcher said, “a way of honouring the animal and its sacrifices.”

Re-enchanting meat eating also entails paying attention to the people involved across the supply chain. Butchers explained to me that modern meat-processing facilities prioritize efficiency to the detriment of animals as well as the people working with them in dangerous, monotonous, and dishonoured jobs. “Is that the world we want?” one butcher mused. “What about us? What really is us? What is our soul? . . . We’ve created a world where we don’t mean anything.” In contrast, a farmer who raises several dozen sheep each year described the joy she feels in her work. “I spend time getting my sheep all comfortable and friendly with me because they are part of my farm family. I am their human, they are my sheep. It’s a mutual relationship.”

We don’t need to be farmers or butchers to develop habits that combine reverence with care for all the creatures and animals involved in our food. Rituals that re-enchant our food practices might be as simple as heartfelt prayers before meals, or as intentional as a church-wide farm visit. We can reduce our meat consumption and learn to cook lesser-valued meat cuts. We can purchase from suppliers who prioritize ecologically sustainable practices, and look for opportunities to buy directly from farmers and local butchers. We can support legislation that protects the safety, pay, and rights of industrial meat labourers, and legislation that enables artisan butchers and abattoirs to operate. We can pray the words Jesus taught his disciples, “Give us this day our daily bread,” as both a memento mori and a reminder of God’s abundant generosity.

Rituals that re-enchant our food practices might be as simple as heartfelt prayers before meals, or as intentional as a church-wide farm visit.

In 2020 as Covid-19 forced meat packers to slow production, the entire meat system crashed into a backlog. Profits across the industrial meat system depend on precisely timed movements, down to the exact day when marginal weight-gain peaks, so the rippling effects of the slowdown caused many farmers to kill piglets by the hundreds and thousands. A farmer I had met through research rescued several piglets from a factory farm and offered me a few. At the same time, the small-scale butcher we depended on was swamped with bookings. The earliest butcher date they could schedule was long after our first pig would need butchering. And so, when the first of these piglets reached maturity, we called a friend with hunting experience to help with the arduous task of butchering. In that year of social distancing, when memento mori was everywhere in our masks and our six-foot spacings, this act of shared labour felt especially significant. I scratched the pig’s ears, brought her tasty scraps, and spoke words of gratitude, just as I’d learned from farmers I’d visited. When the time came and I found myself again watching pig blood seep into the soil, this time I prayed. My children came to watch and help as we worked. We shared stories that reminded us of the connections between these animals, our family, and our faith. We divvied up the meat, then hosted a party where we sat with friends by a fire savouring the first roasted bites, remembering the ways God holds us within a mysterious mishmash of death, life, and love.