I

I’ve been working on an exciting new philosophy of life, cultivating a different way of being in the world, polishing a shiny new weltanschauung. I’m calling it passivism. Here’s how it works.

Activism is about getting angry, refusing to accept the status quo, and agitating for change. Passivism is the opposite of all that. Passivism is about learning to be a connoisseur of letting things happen. It’s about aspiring to be an ordinary dude living your best life now. Its praxis is very mellow. And despite the similar-sounding name and the supposedly similar stance vis-à-vis the world, neither is it pacifism. Most of the pacifists I know, in fact, pitch their tents toward activism. But if you take pacifism and let that terse c stretch out into a couple of languid s’s and soften that f into a v, you’re already getting the vibe. Ah. I for one feel better already.

Actually, passivism and activism are not mutually exclusive. This is not a Corona beer commercial. Passivism is the way to incorporate the inevitability of failure into your attempts to accomplish good in the world. Because let’s face it: change is going to happen to you (It already has! It just did again!), and chances are you’re not going to be able to do a thing about it. Even if you give changing the world the old college try, the likely outcome is that you’re going to get steamrolled by the inexorable force of history and have to accept a world you did not choose or want. Better to do that well than poorly. The more activist you are, it turns out, the more important it is to be a passivist.

Passivism has its share of pitfalls. It’s an easy way to remain ignorant, to shirk responsibility, and to slide into a life of ironically tinged dissipation. It’s possible, in fact, that I have generated this pet theory to justify my enthusiastically sedentary lifestyle. But even if I were to grant you all these things (which I don’t), passivism would still be a necessary aspect of a life well lived. Reality has a way of snapping back into place and smacking you upside the head when you try to bend it. Herewith, then, are ten ways you, too, can become a passivist—or, if you prefer your advice with a dollop of sincerity, here are ten ways to apply Reinhold Neibuhr’s serenity prayer: “Father, give us courage to change what must be altered, serenity to accept what cannot be helped, and the insight to know the one from the other.”

1. Be born

If you have not been born, I highly recommend it. Being born has a wonderful capacity to refresh our sense of the wonder and terror of the world, to enable us to receive its beauty and its splendour and to passively accept it in all its messiness and chaos and ineluctable isness. You cannot control birth; it simply happens to you. You’re so overwhelmed you just cry the whole time. But then, through no grasping or straining on your part, you are given a warm breast to lie on, and a meal, and comfort and nourishment and love—all by the one who gave you your very being. Just because you exist! Being utterly dependent on the goodness and generosity of another is very freeing. As any infant can attest, being born is one of the most amazing and profound ways to experience the sheer givenness of life.

2. Log off

How would your life be different if you didn’t know about the issue you’re incensed about right now? How would anybody else’s? I’d be willing to bet that in most cases the answer would be not at all. It’s not that the issue of the hour is unimportant, just that it might not be within your vocation to be always in the know about it. W.H. Auden: “Instead of asking, ‘What can I know?’ we ask, ‘What, at this moment, am I meant to know?’”

3. Put your own house in order

President Red or President Blue can’t actually do all that much to move the dial of your happiness or the happiness of those you care about. Probably the person with the most capacity to make your life miserable is not on cable news or Capitol Hill but on your city council, or lives in your neighbourhood, or shares your bed at night. And if you’re willing to do a frank inventory of the people who are making your life miserable and who are making the people around you miserable, odds are you’ll discover that you are near the top of that list.

4. Pray the Psalms

If you’re in the business of figuring out how to deal with things beyond your control, boy are the Psalms ever the thing for you. When the psalmist is talking about breaking the teeth of the wicked or hating the enemies of God with a perfect hatred or dashing the heads of Babylonian infants against the rocks, it’s important to recognize that he’s praying those things not doing them, as an Old Testament prof of mine used to say. There’s somebody in charge above all the chaos, and you’re not him (thank God). But he’s there, and he’s listening, and he loves you. Psalms 37 and 73 are especially good on hearing the signal within the static of the world, but also good are Psalms 1–36, 38–72, and 74–150. (Pro tip: they’re all about Christ.)

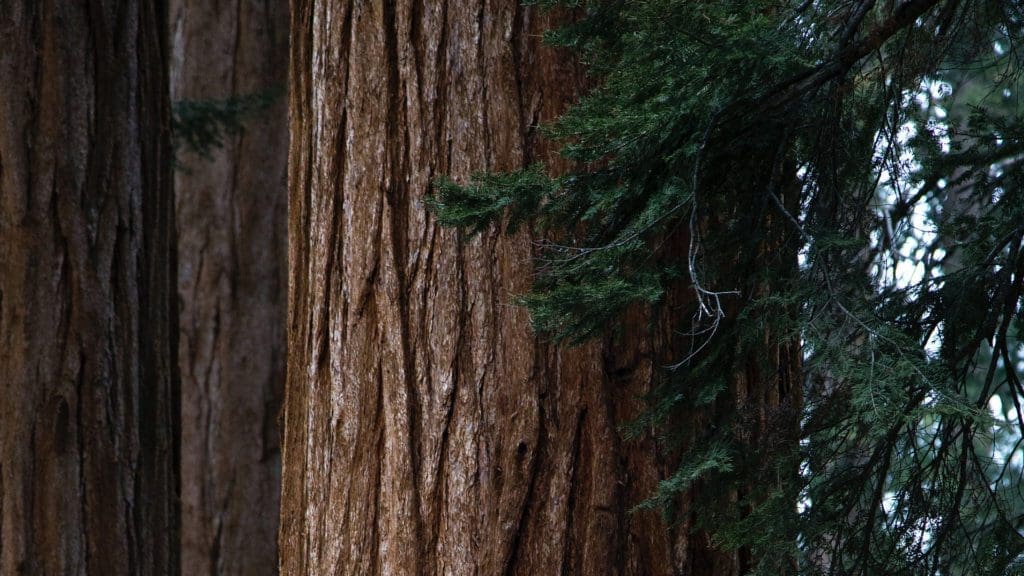

5. Plant a garden

I hate gardening. I know I’m torching all my locavore street cred by saying so, but if you’re an aspiring passivist it’s actually better if you’re no good at growing things. Failure is instructive, and gardening is ripe with metaphors for admitting your lack of control. What do you need to grow something? Sunlight, water, earth. How many of those things did you invent? All you can do is create conditions favourable for the little miracle of growth to occur. And even if you get those things in the right proportion and your plants grow, many other perils lie along the way, most with four or six legs. Frustration is inevitable, and outcomes seem disproportionate to the work involved. Let your garden be your teacher. (If you’re one of those insufferable people who have already mastered gardening and are looking elsewhere for exercises in futility, might I recommend having children?)

6. Suffer

At its root the word “suffer” does not refer to pain but is rather about allowing something to happen. We suffer hardship or pain or grief or want because they are things we undergo, things that happen to us. Passivism shares a root with another word that originally referred to suffering: passion. Suffering can be a great teacher, if we allow it to be, even if that suffering is itself a great evil, or the result of great evil. It cannot but change us, for good or ill. We can suffer poorly, allowing it to embitter us and lead us to despair. Or we can suffer our suffering to illuminate in us the posture of our redemption.

7. Serve somebody

Jesus said it, Bob Dylan believes it, that settles it: You’re going to serve somebody. It’s a phenomenological truth, but it’s also a dominical command. Passivism is not about retreating into a life of privilege. It’s about acquiescing to the shape of reality. And if our Lord taught us anything, it’s that in this world, reality conformed to the love of God is characterized by tending to the needs of others and allowing ourselves to be led where we do not wish to go.

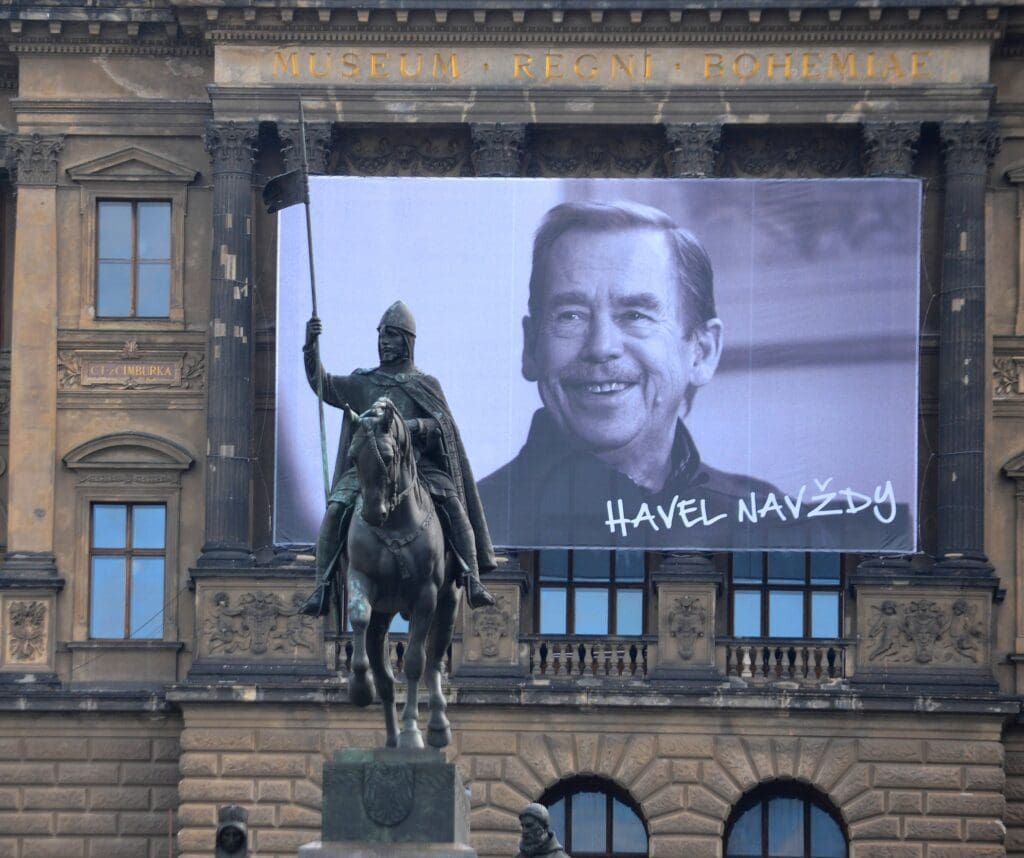

8. Lose a political battle

Sometimes what we’re called to is faithfulness not success. Maybe you’re part of a North American think tank that does excellent research on many topics of social and moral urgency that as often as not falls on deaf ears. Would the world be a better place if your policy proposal succeeded or your request to the city council were approved? Sure. But have you done all that is in your power to do and fulfilled your role in good conscience? Then be content and rest. It is enough. You have done all that has been asked of you. T.S. Eliot: “For us, there is only the trying. The rest is not our business.”

9. Start a project you will never finish

The best kind of change is the kind of change that takes centuries to come to fruition and that is therefore outside our powers to accomplish. A plant that grows up quickly is easily uprooted. A society (let alone an institution, or a family, or an individual) that cannot bear to build something only its future inhabitants will enjoy has lost hope. If you find the prospect of not enjoying the fruits of all your efforts distasteful, consider the example of the architect Antoni Gaudí, whose great masterwork, the Basílica de la Sagrada Família, was not yet one-quarter finished when he died in 1926. Nearly one hundred years later, it is still not finished. When asked about how long the project would take, Gaudí is reported to have said, “My client is not in a hurry.”

10. Die

Next to being born, dying is the best way to embrace passivism. The catch is that you cannot do it to yourself. If you kill yourself you will still die, but you will have squandered one of the great opportunities to receive change well. Dying must happen to you. So you must be ready. And if you are always ready to die well, you will find that when death happens to you, you will have gotten a life well lived thrown in.