T

Three decades ago, in a short piece in the evangelical magazine Christianity Today, I tried to explain why journalists seemed to belittle the moral positions held by people of faith. “Members of the evangelical community have been among the harshest critics of the secular news media,” I wrote in 1993. “What credibility the press had with them was further hurt this February when a Washington Post reporter blamed public opposition to the Clinton administration’s decision to lift a ban on gays in the military on an ‘orchestrated’ campaign by leaders of the Religious Right. In a sentence for which the Post later apologized, the reporter wrote: ‘Their followers are largely poor, uneducated and easy to command.’”

At the time I taught journalism at a nearby university, and the focus of my studies was media and religion. There I found that courses in theology, moral philosophy, or political rhetoric were not part of the curricula for future journalists. As a result, reporters fell into an easy news frame of conflict, cobbling together stories that were mostly sparring sound bites the reporter took from the two opposing sides. “Even when religion gets space,” I wrote then, “it continues to be covered not as faith, or even as sincerely held values, but as conflict between competing interests.” Covering stories via contrary sound bites was also just a lazy way out for reporters, I wrote, quicker and easier than actually taking the time to understand any sincerely held beliefs of people on different sides of an issue.

Since then, not much has changed in journalists’ training. There are those rare examples of journalists going outside J-schools to gain some understanding of people of faith, and the Faith Angle Forum has been heroically bridging these divides for more than twenty years. But few newspaper or broadcast reporters on the political beat can lay out the theology or moral philosophy behind positions of faith and values—and certainly most can’t parse out the rhetoric employed by opposing sides. The result is that the different groups assembled around any given social issue have continued to be largely covered as one group attempting to assert control over others. And the fact that few journalists are equipped to lay out the underpinning ideologies and rhetoric has also meant an easy ride for politicians and candidates who use words to manipulate.

Donald Trump’s bombastic rhetoric became so apparent that eventually news organizations began to check his falsehoods, even as his predecessors had also used rhetoric to vilify their political opponents. Theirs was just more adroit and polished. When, in his 2015 State of the Union address, President Obama alluded to the growing approval for same-sex marriage in appellate courts, he said that he had seen “gay marriage go from a wedge issue used to drive us apart to a story of freedom across the country.” Without overtly insulting his political opponents, Obama positioned them as responsible for the divisions that might tear apart the country, implying that they were opposed to freedom, with which his side was aligned.

The fact that few journalists are equipped to lay out the underpinning ideologies and rhetoric has meant an easy ride for politicians and candidates who use words to manipulate.

The intent here is not to argue for or against same-sex marriage or any other politically charged issue. The concern, rather, is to talk about why we no longer can talk politely and intelligently with each other about those so-called hot-button issues. More and more, moral beliefs are not seen as something that can be, or even should be, publicly debated or discussed. To do so is seen as unfairly infringing on personal rights or personal freedom. The result is that any discussion of faith and values as something principled is now viewed as restrictive and, more and more so, off the table.

The Origins of Our Political Rhetoric

It all started with talk shows. President Obama had joined other politicians of his day in being educated at the Phil Donahue School of Rhetoric. Shows such as The View, The Talk, and The Real all evolved, or devolved (depending on one’s view), from Donahue, which ran from 1967 to 1996 and set the pattern for what values can (and cannot) be praised on talk shows. In 1988, Donal Carbaugh published a book-length analysis of the show’s rhetorical structure. Carbaugh looked at symbols of speech that were either praised or implicitly criticized on the program. References to “individual,” “choice,” and “rights,” he noted, were rewarded, while references to social roles or social structures were either criticized or ignored. (The latter were seen by Donahue and his audience as unfairly value-laden and thus restricting “individual rights.”) In this system of expression, even religion could be stated nearly always as individual choice, not as a system with both benefits and responsibilities.

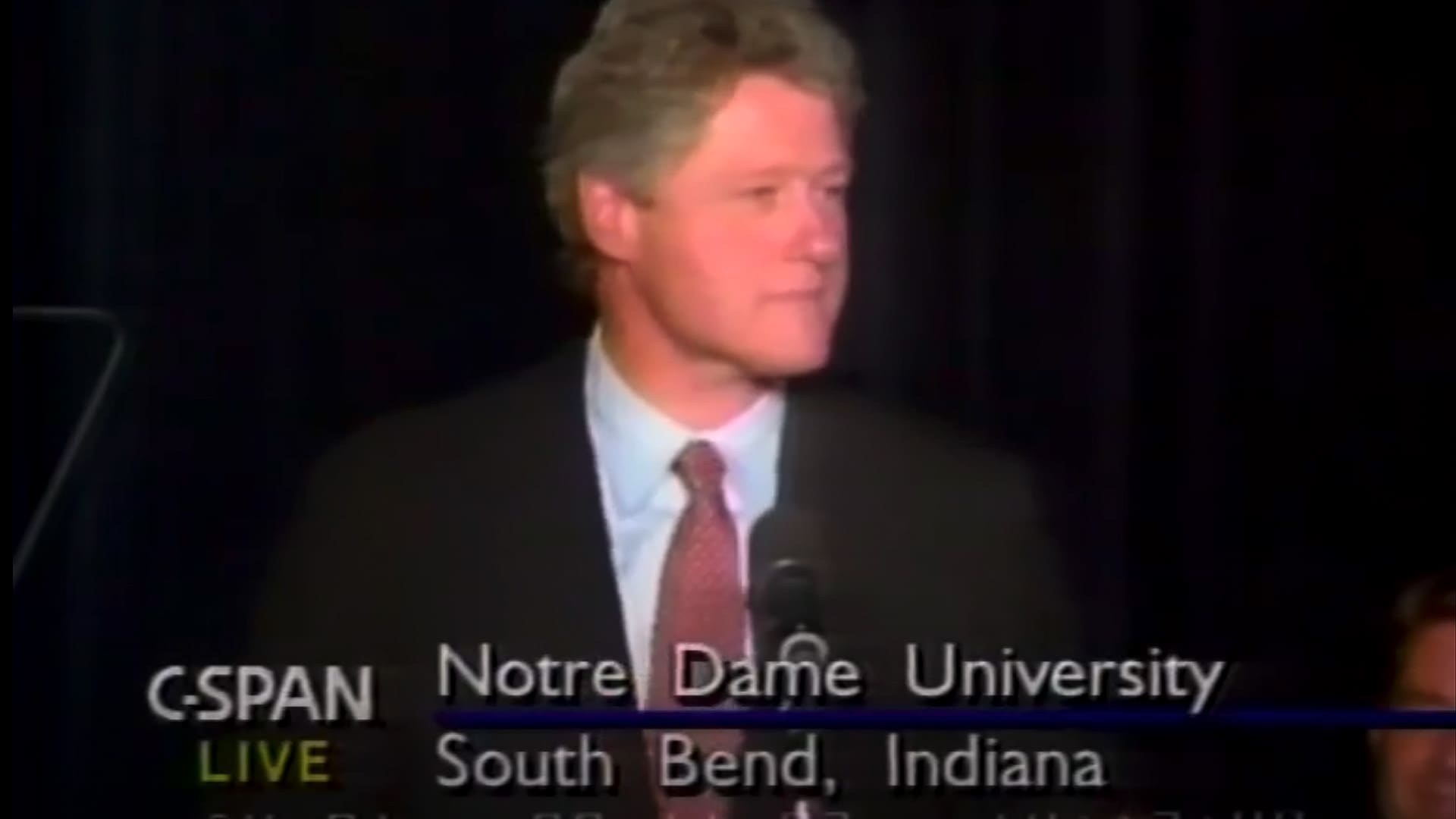

When President Clinton talked about the so-called “family values” issues, he avoided addressing whose values were best. Instead, he routinely framed the issue as a conflict between, on the one hand, those supporting tolerance and acceptance—and, on the other hand, those who would threaten personal freedom and the opportunity to participate in society.

Most Americans first saw this midway through the 1992 campaign, when candidate Clinton delivered what was one of his two major stump speeches that year on family values. It is significant that Clinton chose to make this speech at the University of Notre Dame. There he could expect vocal protests from conservative critics, whom he could use to represent the larger group of anyone who would criticize him on moral or religious grounds. Sure enough, Clinton acknowledged those critics in his opening comments: “Ladies and gentlemen, we know that in this room at least our supporters can win the cheering contest. I would hope that in this great university we could also prevail in the civility contest.” Thus, from the beginning the debate was framed not as a debate over whose values were, in the long run, best for society in a communitarian sense—but as a necessarily disjunctive discourse between those who believe in the correctness of certain values and those who hold to “civility.”

Throughout his campaign and then presidency, Clinton pitted his own desire for a “common ground” against his opponents’ “extremism.” Whatever the occasion, Clinton framed his rhetorical opponents the same. Rather than mentioning them by name, he presented them as placing limitations on the presidency and country—and as being responsible for intolerance and conflict in political discourse.

More and more, moral beliefs are not seen as something that can be, or even should be, publicly debated or discussed. To do so is seen as unfairly infringing on personal rights or personal freedom.

The Loss of Argument

One might ask: well, haven’t politicians always sought to use oratory against the other side? Certainly, but now it is so much easier to do. In Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business, the late American scholar Neil Postman described the first of the seven Lincoln-Douglas debates: “Their arrangement provided that Douglas would speak first, for one hour. Lincoln would take an hour and half to reply; Douglas, a half hour to reply to Lincoln’s reply.” The printed word made accessible by Gutenberg had helped engender in people a discipline for a prolonged engagement with ideas and helped develop in them a habit of contemplation of a text, a dexterity carried over to following the intricacies of long sermons or oral arguments. Postman reminds us, “That the audience was able to process it through the ear is remarkable only to people who no longer resonate powerfully with the written word.”

Today, connections are made with audiences not with carefully laid out arguments but with quick quips and fleeting, largely visual media images. During the 1992 presidential campaign, Bill Clinton sought to create emotional connections with voters by picking up his saxophone on The Arsenio Hall Show and, during the second presidential debate, picking up the microphone to walk into the audience à la Donahue. At year end, Clinton had participated in forty-seven talk shows to independent candidate Ross Perot’s thirty-three and incumbent George H.W. Bush’s meager sixteen, setting a pattern for today’s presidential candidates, who to humanize themselves continue to hit the talk shows and Saturday Night Live.

A reliance on easy visual symbols of intimacy makes it easier for politicians to abuse the spoken word, in the case of Bill Clinton, and more than a few subsequent politicians, taking up the libertarianism found in the speech codes of TV talk shows—and using such rhetoric to their own advantage. In January 2005 Senator Hillary Clinton, nearing the end of her first term as senator from New York, spoke on the thirty-second anniversary of Roe v. Wade. The senator began her remarks by calling attention to policies in Romania under Nicolae Ceauşsescu, who had made it illegal for women to seek abortions, and in China, which had forced women who became pregnant again after having one child to have abortions or be sterilized. Thus, from the beginning the most important issue in the argument over abortion was not a question of whether abortion was the taking of a life or whether such questions might be outweighed by concern for the woman’s physical or emotional well-being. Rather, those who opposed abortion were grouped with the brutal, hardline, dictatorial regimes that sought intrusive control over their people’s private lives.

2015 Republican presidential primary debate, FOX News.

1992 campaign at the University of Notre Dame.

2015 State of the Union address.

All this is helpful to understanding the rhetorical appeal of Donald Trump. Candidate Trump struck a chord with a sizeable portion of the electorate who felt themselves squeezed out of the national conversation. Yes, Trump’s rhetoric was more overtly vitriolic than that of his predecessors. But he met with success because he could co-opt a feeling of alienation and pent-up frustration on the part of those who might be called the moral conservatives, people Trump’s political opponent in 2016, Senator Clinton, in an off-the-cuff remark even dismissed as “deplorables.”

No attempts at niceties governed his rhetoric. Of the insults and taunts handed out by candidate Trump, a few early on stand out for their special viciousness. In August 2015, in the first presidential debate, Megyn Kelly questioned candidate Trump about his contentious Twitter comments demeaning women: “You’ve called women you don’t like ‘fat pigs, slobs, and disgusting animals.’” The audience at home saw something now familiar: Trump did not display any sign of censure or reproof. He first tried to make light of his crass remarks, joking that he meant to offend “only Rosie O’Donnell.” In a clever rhetorical move, he then sought to bond with his supporters in a disdain of civility. “The big problem this country has is being politically correct,” claimed Trump. “I’ve been challenged by so many people, and I don’t frankly have time for political correctness. And to be honest with you, this country doesn’t have time either. This country is in big trouble.” Trump thus excused his personal rudeness by shifting attention to the needs of the country, which, he said, required a gruff leader who didn’t have time for niceties. Even when caught being crass or vulgar, Trump depicted his behaviour as a necessary corrective to an elite status quo who, having given in to political correctness, were too weak to stand up for Americans. “We need strength, we need energy, we need quickness, and we need brain in this country to turn it around,” Trump told Kelly.

By early 2016, Trump had set himself off from the other candidates by his scurrilous ad hominem and name-calling: “Low Energy Jeb,” “Sleepy Ben Carson,” “Crooked Hillary,” “Little Marco,” “Lyin’ Ted,” “Crying Chuck,” and so forth. Sometimes, though, the rhetoric was less overt. A rhetorical sleight of hand Trump favoured was what is called praeteritio, insulting someone while denying that one is actually saying that thing. Perhaps he thought of himself as particularly clever in his use of praeteritio, because he used it over and over. For example, he said to Marco Rubio, “I’m not going to call him a lightweight, because I think that’s a derogatory term.” And one example among thousands of derogatory tweets was his January 2016 retort that “I refuse to call Megan Kelly a bimbo, because doing so would not be politically correct. Instead I will only call her a lightweight reporter!”

For Trump, being criticized himself did not bring self-examination, of which there seemed nary a trace in the candidate. His was a heart seemingly impervious to moral reproof. This was a man, after all, who during the 2016 debates declared that he didn’t think he had ever done anything that might require confession in a church. There was no elegiac quality to his comments, no understanding of any human limits, no self-reflection.

His willingness to be rude also assured him more media exposure than other candidates were given. Trump’s 2016 and 2020 campaigns both appealed to his constituency’s coarser interests. In an age of increasing spectacle, the way to gain attention is situationist pranks, rebellious acts as fodder for the media. Trump’s rhetoric seemed fitted to a time of heightened resentment and anger: he exploited a nagging feeling on the part of his supporters that they had been talked down to by previous candidates and gave them permission to reply to other people’s more-polished rhetoric with simple insults, crass vulgarities, and even violence.

A feeling of being humiliated and ostracized can be a distressing event in someone’s life, and can lead to what British philosopher Miranda Fricker calls “epistemic injustice.” Not trained to parse rhetoric, and with few in the news media doing it for them, many moral conservatives felt mocked. They felt pushed out of political conversations by an arrogant elite and did not know how to fight back. Confounding to the people of Sarah Kendzior’s “flyover country” was that individualism was now seen as the hierarchical value to override all others. There seemed no allowance any longer in public discussion for their beliefs or even talking about the possible pros and cons of different cultural values.

In a society where people of different ideas cannot, or will not, sit down together to take up and mull over their different positions on an issue, there can be said to be an epistemic injustice. Politics is no longer the civil town-hall community gatherings held up as a model by de Tocqueville. Rather, politics becomes a contest to eliminate, outshout, or otherwise marginalize the other person. This contest of catchphrases and memes has led to a regrettable repercussion. When we do not permit the other side a seat at the table, when we delegitimize the other side, society lacks an interpretive framework and a shared vocabulary to communicate our experiences to each other. Indeed, there is no longer a shared community. Lost to society is the opportunity to honestly debate or to intelligently discuss moral or social positions.

When we do not permit the other side a seat at the table, when we delegitimize the other side, society lacks an interpretive framework and a shared vocabulary to communicate our experiences to each other.

The Recovery of Sympathetic Understanding

What then to do? Can any common ground be found? Psychologists William Damon and Anne Colby, in their 2015 study The Power of Ideals: The Real Story of Moral Choices, call for a shift away from mere cognitive-developmental models of moral decision-making. It is not enough to be told to act morally and to be told what constitutes proper moral behaviour. A disposition to care about others must be developed. We need not only an intellectual understanding of another person’s position but also a sympathetic understanding of persons who are different from us. We must overcome our familiarity bias, a bias to care only, or nearly exclusively, about those in our family, our closest friends, or those in political agreement with us. Do we have the ability to redirect our emotions beyond those circles?

One of Damon and Colby’s examples of someone who showed sympathetic understanding toward others was Nelson Mandela. In twenty-seven years of imprisonment, he lost decades of time with his family, as well as his personal freedom and comfort. But after he was freed and became president of South Africa, he gave up any desire for revenge in order to work to bring together his people. Mandela had achieved a complex moral understanding in part from seeing his own humanity recognized by people on the opposing political side, even while he was in prison. He described being able to distinguish between those guards who treated him cruelly and those who treated him with dignity.

Sincere humility includes a desire to understand one’s own weaknesses and imperfections and to be open and receptive to learning from others. It is in that undertaking that we gain wisdom and discernment. There cannot be a desire to punish or diminish one’s political or moral opponents. The moral exemplars Damon and Colby highlight each had a firm conviction in their own principles but showed humility when tempted to assert power over others. For many of the exemplars, faith helped them identify what was important, what was ultimately lasting, what was worth devotion. The person who has faith ideally has an examined life that brings reflection and humility.

We lack a complex life if we only associate with like-minded people, if we persist in the assumption that if someone is not our ally then they are an enemy. Nor will we develop a complex life if our faith is reduced to platitudes with no real investment in others’ lives. The unexamined life can lazily fall back on pat answers. People who resort to sloganeering and blanket insults need never examine the validity or the effect of their own beliefs. In her prescient 1937 essay “The Power of Words,” Simone Weil connects speaking in bald absolutes with a hypocritical blindness to the ways in which we compromise our own ideals. Weil writes, “This is illustrated by all the words of our political and social vocabulary: nation, security, capitalism, communism, fascism, order, authority, property, democracy. We never use them in phrases such as: There is democracy to the extent that . . . or: There is capitalism in so far as . . . The use of expressions like ‘to the extent that’ is beyond our intellectual capacity.” Weil reminds us that only with difficulty can we admit any compromises and contradictions in our own lives—or any good in the opposing side.

We lack a complex life if we only associate with like-minded people, if we persist in the assumption that if someone is not our ally then they are an enemy.

Trump, in his transactional politics, simply lacked a concept of moral consideration. The give-and-take that allows animated disagreement among people of differing opinions just wasn’t there. He didn’t provide any résumé of intellectual influences but rather postured himself as a self-made man, embodying an ideal of a priori self-origin. To a journalist’s question about the president’s moral thinking, former Bush advisor and Trump critic Peter Wehner exclaimed, “We’ve had presidents who were more moral or less moral. We’ve never had a president who takes psychic delight in shattering moral norms.”

To move from discord to discourse, we would do well to listen for those moments out of time, for some lasting truth, something that was there yesterday and will still be there tomorrow. And we need to disavow our own abuses of rhetoric, from whichever end of the political spectrum. In October 2020, Pope Francis, in his third encyclical, warned that a rhetoric of division was a stumbling block to global cooperation and peace:

The best way to dominate and gain control over people is to spread despair and discouragement, even under the guise of defending certain values. Today, in many countries, hyperbole, extremism and polarization have become political tools. Employing a strategy of ridicule, suspicion and relentless criticism, in a variety of ways one denies the right of others to exist or to have an opinion. Their share of the truth and their values are rejected and, as a result, the life of society is impoverished and subjected to the hubris of the powerful.

I don’t have the thick skin needed to seek political office, but if I were ever elected to anything, one of the first things I would do is to ask for a meeting with my opponent. I would ask him or her what it is that I am overlooking and what ideas I could learn from the other side. I hope that I would treat the other person as someone with good intentions and some good points I might be overlooking. A chief virtue of good leaders is humility. A leader who seeks humility is likelier to be introspective, to realize limitations, to seek ideas from others, and to be collaborative—and to avoid abuses of rhetoric for personal advantage. If these kinds of aspirations for our leaders seem unrealistic or quixotic, that only displays how cynical we have become in our expectations for our politics. If only those in charge, and those who vote for them, on whichever side, would realize this. And that we would each labour to listen to the other.