O

The language of spiritual ascent is not unbiblical, nor is it altogether harmful. But ascent language can, and often does, reinforce a false mental map that leaves us in control of our religious destiny.

—John Newton, Falling into Grace

Humility: Her name is Mary.

—St. Bridget of Sweden

On my first, and possibly my last, visit to the earthly Jerusalem, I found myself at the Wailing Wall watching a young girl pull at her father’s prayer shawl. As his forehead gently thudded the stone, she kept crying, “Abba,” hoping he would turn and pick her up. Theirs was a dual petition. Eventually, the father yielded to her request; and I expect that in time God will yield to the heart of his petitions as well, whatever they might have been.

The mood of the city that evening reminded me of the eight o’clock hour at a New Jersey diner, with most of the customers about to head home and weary servers eager to do so as well. The summer sun caressed the horizon, and the Herodian ashlars—the forty-foot-long, 350-ton stones of the temple foundation—exhaled a day’s worth of heat. I let those stone walls lead me onward, and they directed me beyond themselves, depositing me outside the city proper through what is known as the Dung Gate. I wandered the busy road that hugs Jerusalem’s ancient contours and made a crisp descent into the Valley of Jehoshaphat, also known as the Kidron Valley, at the base of the Mount of Olives. There I saw the trees that constitute what is left of the Garden of Gethsemane.

The area looked relatively undisturbed, as if blood could have been sweated there just last Thursday. As a rooster crowed, I walked to the garden’s entrance, noticing to my disappointment that the gate was closed. I looked in on the caged garden as best I could, but a hostile dog ensured I kept my distance. The gnarled, squat tree trunks contrasted with the smooth city walls and what remained of the temple that towered so high above them. I did not think it possible to sink much lower than this valley of torment, which Jesus had consigned himself to when he refused what was offered to him from the temple’s highest point. Even Calvary, on the other side of the city, was a hill. Just as I prepared to leave, I spotted the entrance to a cave beneath the Garden of Gethsemane itself.

Both images: Mary’s tomb below the Garden of Gethsemane.

Photo by Dennis Jarvis.

Photo by author. (All photos by author unless otherwise noted.)

Mary’s Funeral

My guidebook told me that this cavern, known as the Tomb of the Virgin, would—like the Garden of Gethsemane—be closed at this hour. But for some reason the doors that opened into its depths were ajar. I approached the entrance, imagining the imposing Byzantine and Crusader churches that once stood on the site. Those churches have long since been destroyed. Only these depths remain. And depths these certainly are. Old depths. The cave church I was about to enter was carved into an ancient necropolis that dates to the first century AD.

The first twenty or so steps down into Mary’s darkened tomb felt like a refutation of those who insist Christianity is best defined by triumphalist arrogance. The next twenty or so, much less comfortably, felt like a refutation of the triumphalist arrogance that lingers in me. With each step down, the air got cooler and my heart grew calmer. The staircase is so long that there are devotional way stations en route—pious pit stops—to accompany pilgrim spelunkers, who can light candles and reflect on events in Mary’s life. But the base of this biographical stairway marks the end of Mary’s earthly life, presenting the material remains of her funeral.

Mary’s tomb below the Garden of Gethsemane.

Mary’s tomb—empty owing to the tradition of her body’s assumption into heaven—is behind a cluster of tacky gilded paintings of the funeral itself, with a bad copy of Leonardo’s Last Supper thrown in to ward off the art snobs. In the iconography for this event, known in the East as the Dormition (falling asleep) of the Theotokos (Mother of God), Mary’s carrying of the infant Christ is reversed, as son carries mother instead. (I expect anyone who has had to care for aging parents, or who has witnessed them die, can especially relate.) If Mary’s soul is tiny in depictions of this occasion, the door to the tomb itself is deliberately tiny as well.

Tradition relates that in this subterranean chamber all the apostles showed up for the funeral, including Paul. Those more far flung, like the apostle Thomas in India, required miraculous travel assistance, but they still made it. The event lends an unexpected resonance to Joel 3:2: “I will gather all the nations and bring them down to the valley of Jehoshaphat.” The Dormition homilies—that great repository of rhetorical and devotional flair that celebrates this occasion—repeatedly suggest that the event of Mary’s death is not just about her death but about the death of all of us as well. I suppose, then, visiting the cave of the Dormition is like attending your own funeral in advance, when God will tend our souls as carefully as Christ tended the soul of his mother as depicted in the icons. There is good reason nearly every Orthodox church places an image of this event near the exit, making for an inescapable memento mori. But maybe the cave of the Dormition is also about a different kind of death. “If you die before you die, you won’t die when you die,” reads ancient monastic counsel often emblazoned on monastery walls. The descent into Mary’s tomb speaks to this kind of ego death as well.

Visiting the cave of the Dormition is like attending your own funeral in advance.

I crawled into the tomb itself and saw Mary’s marble funeral bier encased in glass—or was it Plexiglas? A pile of crumpled banknotes had been stuffed inside as offerings. Exiting the tomb, I walked around it and discovered a much larger chamber, where a Russian monk was engaged in quiet conversation with a young couple; but otherwise I had the place to myself. Or did I? In this larger room I saw the Panagia Ierosylimitissa icon—Our Lady of Jerusalem—a miraculous image of Mary with her son painted sometime in the nineteenth century. In the competing miracle accounts of this icon, the painter was a woman, either Tatiana the Greek or Sergiya the Russian. Whoever it was, they got Mary right. One modern monk who claims to have seen the Virgin in a vision says that this particular icon resembles her more than any other. If you don’t believe him, you might at least admit the story has charm.

Mary’s tomb below the Garden of Gethsemane.

Despite the glow of the icon, the primary experience that this space offers is darkness. Dionysius the Areopagite, the Syrian monk who assumed the name of the man converted by St. Paul in Acts 17, but who in fact penned his Mystical Theology around the year 500, claimed to have been present at Mary’s funeral in this very spot, which he probably visited. Perhaps the experience helped inspire his writing about divine darkness, “a truly mystic darkness, within which he closes out all knowing and perceptions and comes into That Which is wholly untouchable and invisible.” (Dionysius is often accused of being more Platonic than Christian, but there is no such account of divine darkness in Platonism.) Nor has this ancient taste for Christian depth ever abated. In a recent ethnographic study of the modern rituals surrounding Mary’s tomb, Nurit Stadler argues that this site indeed illustrates that Mary functions as “mother of minorities” and “mother of the oppressed.” Mary here becomes “a vehicle to voice discontent.” The modern celebration of this event on August 15 culminates with a ritual of crawling under the woven icon of the Dormition, which annoys the presiding clergy considerably. It seems even these depths aren’t deep enough. Those who venerate the Virgin Mary here aim to go lower still.

Entrance to the grotto of the Nativity in Bethlehem.

Silver star at the traditional spot of Jesus’s birth.

More Marian Descents

A visit to Mary’s tomb outside Jerusalem in no way exhausts Christianity’s underground dimensions. The next day I found myself in Bethlehem. The journey from Jerusalem into Palestinian territory itself entails a descent into relative poverty. Then there is the descent required to enter the Church of the Nativity, through a low doorway just like the entrance to Mary’s tomb. Annie Dillard gets it right when, describing this church, she remarks that “each polished silver or brass lamp seemed to absorb more light than its orange flame emitted, so the more lamps shone, the darker the space.” But even this is only preparatory darkness. Next comes the descent into the cave of the Nativity down a semicircular staircase. On reaching its base, one then stoops down even lower to touch the fourteen-pointed star that encircles the very site where, Christians believe, God “emptied himself, by taking the form of a servant, being born in human likeness” (Philippians 2:7). This is the Grotto of the Nativity, and the place of Christ’s emergence looks—fittingly—like the clogged drain of a shower. No one said the cleansing of the world would be tidy.

The place of Christ’s emergence looks—fittingly—like the clogged drain of a shower.

“Banksy, never again,” muttered our guide over and over as we waited too long at a checkpoint on the road back to Jerusalem. He had unwisely yielded to one tourist’s request to see the famous artist’s murals on the West Bank Wall. But we did make it back. The next day as I wandered Jerusalem under a blazing July sun, this pattern of depth reasserted itself. I saw a sign off Jerusalem’s main street, known as the Cardo, that announced one building to be the birthplace of the Virgin Mary. Entering it also involves a long descent of multiple, increasingly narrowing staircases until one finds oneself alone in a cool, dark cavern, the onetime dwelling place of Jesus’s maternal grandparents, Joachim and Anna. In this cave the Virgin Mary was brought into the world, making it possible—not very long afterward—for God to enter it by cave as well.

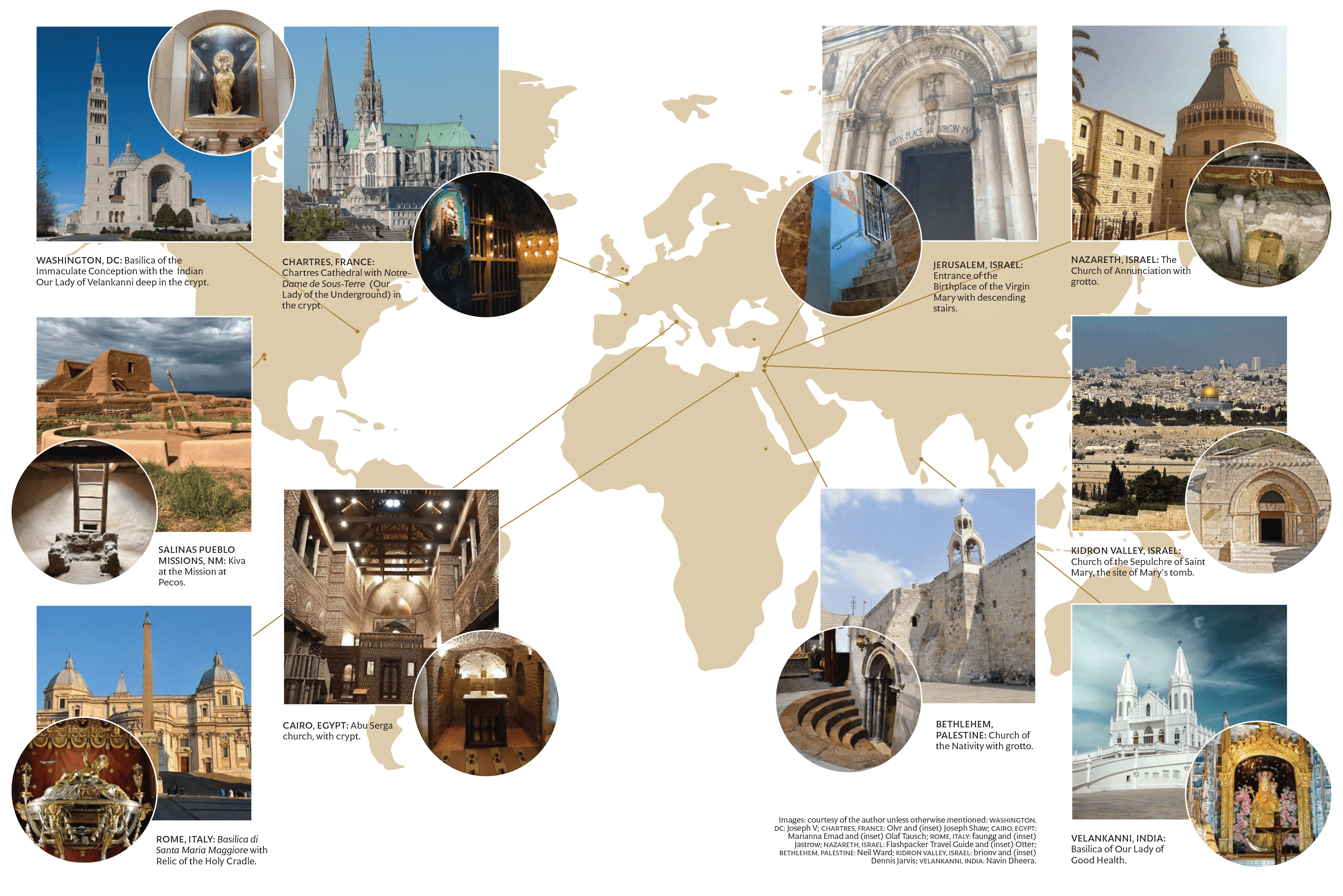

Mary’s life, it turns out, began in depth and ended there, with considerable depth in between, as at the Church of the Annunciation in Nazareth. Seeing the place of Gabriel’s tidings also entails a descent from an imposing upper church to a quiet place far below, known as the Grotto of the Annunciation. Christianity, it seems, is regularly marked by subterranean silence, while the noisy world clamours and cavorts above. On a visit to Cairo years ago, I went to one of the places where Mary and Joseph and the Christ child presumably stopped on their flight into Egypt. Seeing the place of their visitation entailed exiting the grand upper church of Abu Serga down a stairway to a hidden chamber far beneath the main structure. In that chamber, the riotous streets of Coptic Cairo give way to silence and even secrecy, as if Herod’s soldiers were pursuing the Holy Family still. Indeed, when an ISIS bomb shattered Palm Sunday celebrations in the same part of the city shorty after my visit, it was as if they were.

Christianity, it seems, is regularly marked by subterranean silence, while the noisy world clamours and cavorts above.

Both photos: The Birthplace of the Virgin Mary in Jerusalem.

The Birthplace of the Virgin Mary in Jerusalem.

Marian Humility

There are, I am well aware, archaeological reasons for all these descents. As time passes, cities build on top of older layers. Hence modern living is mostly a surface phenomenon, and examination of the past entails exploring dimensions down. But archaeological facts do not rule out spiritual ones. I think there is something more than academic in the fact that the life of the Virgin Mary is held together by a network of subterranean sites. I should add here that by the Virgin Mary I do not just mean the historical Mary, although I do mean her as well.

Mary in Christian history can and does mean many things. She is at once a historical figure and an image of the church and an image of the soul and an image of the mysterious biblical figure of Wisdom in Proverbs’ eighth chapter. “Whatever is said of God’s eternal wisdom itself,” wrote the twelfth-century Cistercian Isaac of Stella, perfectly summarizing this polyvalence, “can be applied in a wide sense to the Church, in a narrower sense to Mary, and in a particular way to every faithful soul.” So when we talk about these Marian depths, we are also talking about our own descent, individually and collectively, into humility.

I am tempted to say we need such a humble Christianity now more than ever, but that would be to assume there was ever a time when it was not needed. A humble Christianity has always been necessary, will always be necessary, and will probably always be rare. Such humility has nothing to do with obsequiousness; still less does it offer permission to settle for our own sinfulness. Nor can it be equated with that dubious modern virtue of “authenticity.” Instead, humility is the state of the God-dependent ego after its own funeral. Humility is the welcome embrace of our nothingness without God. For St. Bernard, humility was not so much a virtue as the foundation and guardian of all virtue. Hence T.S. Eliot infused East Coker with this: “The only wisdom we can hope to acquire / Is the wisdom of humility: humility is endless.” If I remind you that “humility” derives from its parent word humus, Latin for “earth,” the fact that you might know this already will hopefully not keep you from the humility required to let that etymological fact freshly impress you. Humility is indeed earth-bound, as we are, which may be why Christian architecture is so much more than a throng of domes or a web of vaults. The pinnacle of Christian architecture, Marian churches tell us, is marked less by a pinnacle than by a pit.

The pinnacle of Christian architecture, Marian churches tell us, is marked less by a pinnacle than by a pit.

Beyond the Holy Land

Christian architecture is also marked by attempts to replicate Jerusalem in disparate places. It should come as no surprise that these Marian descents are replicated outside the Holy Land. Take Rome’s greatest Marian church, Santa Maria Maggiore, proudly perched on the Esquiline hill to mark—we are told—the miraculous site of an August snowfall. Visitors to this “Bethlehem of the West” are first met with splendour. An ancient icon (the Salus Populi Romani) and sixth-century golden mosaics give way to Renaissance frescoes by Piero della Francesca, which in turn yield to seventeenth-century baroque opulence, so much so that even Bernini himself is buried here. But to visit what is left of the crib, the Santa Culla (holy manger) of the Christ child, necessitates descent. Just before the grand baldacchino, a stairway leads one flight down to a massive statue of Pope Pius IX frozen in permanent prayer, and then another flight down to where, encased in a sumptuous rock crystal reliquary shaped like a cradle made of seventy types of marble, there are just some sticks: five humble sycamore sticks that do indeed date back to the time of Christ and that would have once been above that shower drain in Bethlehem. Similar depths can be encountered beneath Rome’s Basilica of San Clemente, where humble frescoes of Mary and child contrast with their more dazzling depictions in the upper church. Then there are the catacombs themselves, hosting some of the earliest images of Mary and Jesus, images that gently check the Christian imperial pretensions of the city above.

Such Marian depths continue at the queen of all Gothic sites, Chartres Cathedral. Tourists make their way there for its famous flying buttresses and the quadripartite perfection of its ribbing, often satisfying themselves with that. But pilgrims go deeper, finding themselves lost in the crypt. Here the debates about whether Chartres’s recent interior restoration was justified, which whitened her dark walls and lightened the face of her Madonnas, are irrelevant. Darkness is still the signature of this space, where the black Notre-Dame de Sous-Terre (Our Lady of the Underground) awaits. The original statue was taken by French Revolutionaries who clamoured for so much light and clarity that they burned her on the steps in 1793. It did not take long for Christians, who are more comfortable with darkness and depth, to bring this dark woman back, hence the copy one sees in the crypt today.

Notre-Dame de Sous-Terre (Our Lady of the Underground), in the crypt beneath Our Lady of Chartres Cathedral, Chartres, France. Photo: Joseph Shaw.

Native North America

When the Catholic bishop of Montreal visited Chartres in 1841, he descended to the crypt and was stunned to discover a wampum belt lovingly woven by the Huron-Wendat people that he knew so well (see my “A Northern Guadalupe,” Comment, December 18, 2023). It was a gift from indigenous devotees to the Virgin of Loreto from the mission just outside Québec City. At their settlement at Loreto, where Mary was honoured and loved, the Huron-Wendat pointed out where their descendants had emerged from a hole in the ground. No wonder the wampum belt they created was kept in the crypt of Chartres and not fastened to its towering heights.

This downward devotion is a feature not only of the Huron-Wendat but of a great number of Native American cultures. Choctaw theologian Steven Charleston puts it this way, referencing the southwestern subterranean focal points of devotion known as kivas:

The kiva serves the same function as a cathedral, as a place of worship. Yet while a cathedral’s soaring arches or a mosque’s great domes are designed to point us upward, the kiva is intended to point us downward. The spiritual focal point is not above us, but below. We are not to look up, but down. What we seek is not in the sky, but in the earth. . . . The kiva points us in a new direction: not an escape from this world, but an entering into it. The kiva is a womb. It is a place of origins . . . a place of darkness.

Kiva near the church at San Gregorio de Abó Mission in New Mexico.

Charleston’s words fit perfectly with the architecture of descent in the Marian churches of the Holy Land and Europe. No wonder that amid heavy-handed missionary tactics and the even more brutal oppression of colonization, flashpoints of early Christian mission work appear to have embraced the kiva. One scholar, referencing the San Gregorio de Abó site among the Salinas Pueblo Missions in what is now New Mexico, claims that “a certain co-existence between the kivas and the churches was tolerated by the Franciscans prior to 1660.” I decided this was interesting enough to make a visit myself. After a long drive through the desert outside Albuquerque, at the base of the Manzano Mountains, there it was: an early mission complex where the kiva was not filled in or destroyed but nestled right next to the church.

According to Christopher Vecsey in On the Padres’ Trail, the Catholic faith was initially proclaimed in the great kiva at Pecos just outside Santa Fe. This kiva, too, is placed near the main mission church, as missionaries slowly learned to work with, not only against, indigenous traditions. Here one can descend the ladder and go inside, replicating the visit to Mary’s tomb in Jerusalem. As I sat there in silent prayer, the feet of two visitors jumbled above me. “Must be a storage shed,” a husband said to his wife. “I’m not going down there.” They moved on, leaving me to my prayers.

Kiva and mission church at Pecos National Historical Park.

Deacon at the nearby St. Anthony’s Church with the Marian image that joins the Pueblo celebrations.

Later I met a Catholic deacon in Pecos who participates in the annual Pueblo celebrations at this site during the Feast of Nuestra Señora de los Ángeles de Porciúncula on August 2. An image of the Virgin Mary from the nearby church of St. Anthony is brought to the Pecos Pueblo site and is honoured while visiting Jemez Pueblo dancers enter reverently into the kiva. Despite what some of the park rangers and academics will tell you, the Pueblo people and the Catholic church of Pecos still work seamlessly together, and—at least on this occasion—the kiva and the cross become one. Maybe this is due to a deep kinship of humble Marian descent. Not identifying this kinship earlier, and even violently suppressing it, remains one of the many missed opportunities of Christian missionary work, one that is being redressed today.

Endō’s Missing Descent

Steven Charleston is not the only one who has called for descent as compensation for triumphalist Western Christian tactics. The last literary product of Shūsaku Endō, the Japanese Catholic author of the justly famous novel Silence, is his aptly named book Deep River. In it, Endō further explores the gap between Asian cultures and European Christianity. The main protagonist in this novel still experiences a prejudice against Japanese Catholicism on its own terms. But, as I learned from my colleague Miho Nonaka and my former student Claire Wagner, Endō’s quest for Japanese Christianity entails a search for indigenous maternal descent.

In Deep River, a disparate group of Japanese tourists make their way to Varanasi on the Ganges in India in search of healing. While there, some enter a deep, womb-like chamber, where they encounter the Hindu goddess Chāmundā. Like Mary, Chāmundā is an affectionate mother. “But unlike Mary, she is not pure and refined, and she wears no fine apparel. Rather, she is ugly and worn with age, and she groans under the weight of the suffering she bears.” Chāmundā, in Endō’s words, is “utterly different from the lofty, dignified Holy Mother of Europe.”

Endō never renounced his Catholicism. In fact, he concludes Deep River—in my reading at least—by suggesting Jesus is the Ganges. “I can’t leave the church,” the protagonist says. “Jesus has me in his grasp.” But it might be fair to suggest that his quest for a Christianity with maternal depth went unsatisfied, hence his need to find it in Hinduism instead. Even though he spent time in Jerusalem, Endō did not, so far as I know, visit Mary’s darkened tomb.

I visited Varanasi myself, tracing Endō’s imaginary journey in Deep River. I could not find any trace of this underground Chāmundā temple. I suspect it was a literary construction, with Endō transplanting a different Chāmundā temple and its underground cave to Varanasi for narrative convenience. But I added a leg to my trip that Endō was unable to make. I went to that most famous of Indian Marian pilgrimage sites, Velankanni, Our Lady of Good Health, known as the Lourdes of the East (see “After Zen, Mary,” Comment, December 11, 2023). On my arrival, I walked to the upper basilica and found it deserted. I finally got someone to let me in, and they appeared particularly puzzled by my presence at this part of the sanctuary. The virtually empty Lourdes of the East was certainly not measuring up to my expectations.

Basilica of Our Lady of Good Health in Velankanni, India. Image: Navin Dheera

Until I realized that the real action was far below. It was in the lower basilica where everyone had gathered. That is where the shrine’s central statue lies, as well as throngs of shoeless pilgrims. This was the part of the world that suffered most from the great tsunami of 2004, which struck on a Sunday, the second day of Christmas, which meant the sanctuary was filled with people and the Lourdes of the East became an impromptu mass tomb.

That the shrine is still thriving today despite this appalling tragedy testifies to a suffering, sorrowing Christianity that endures. Perhaps the prospect of healing after such a harrowing event shows that Mary’s compassion is gritty enough to rival Chāmundā. This lesson might apply beyond India as well. In Washington, DC, the soaring Byzantine architecture of the National Basilica of the Immaculate Conception is Catholicism’s defiant answer to the Gothic style of the Washington National Cathedral, which is officially Episcopalian. The Catholic basilica is packed with sumptuously decorated chapels celebrating the Virgin Marys of the world. Fittingly, the chapel dedicated to Our Lady of Velankanni is kept beneath the gargantuan basilica, deep in the crypt. If any place is in need of a humble, deeper Christianity, maybe it is Washington, DC.

If any place is in need of a humble, deeper Christianity, maybe it is Washington, DC.

“A Very Deep Valley”

I wonder whether this network of Marian depth could ever fully be charted. There is a St. Mary Undercroft chapel tucked into a corner of Westminster Hall in London, and there is a Mary in the crypt of Canterbury, known as Our Lady of the Undercroft as well. There are images of Mary in the Dark Church of Cappadocia and in the rock-cut churches of Ethiopia and in replica Lourdes grottoes the world over. There is even a Lutheran rock-cut church in Finland. And when we’ve tired of going underground, we can go under water, to the dark clay statue known as Aparecida, which was pulled from the sea by some fisherman and is now the patroness of Brazil. Some Marys are still under water, such as the statues of the Virgin placed on the ocean floor near the Philippines to prevent ecologically ruinous dredging. Then there is what is commonly called the “underground church”—that is, the persecuted church—of any epoch, with which Mary has been identified since the writing of Revelation 12. These Christian depths attract contemporary artists. Writing of the descending black Madonnas that fascinate Chicago artist Theaster Gates, one critic writes that he “seemed to seek out the shadowed aisles, hidden crevices . . . rather than the central nave of the cathedral’s beautifully lit space.”

An entire spirituality may be contained in these descending Madonnas, for again she represents not just herself but all of us. For every Western Christian mystic who speaks of the exalted heights, there is one who speaks of the Grund. Meister Eckhart insists that “in the ground of divine being, where the three Persons are one being, there she [the Marian soul] is one according to the ground.” Eckhart’s is an irreducibly trinitarian theology of mystical Marian darkness and descent. No wonder Carl Jung was so drawn to him, detecting in Eckhart a cure to the Christian shallowness that Jung’s “depth psychology” attempted to address. In the words of Sergius Bulgakov, “There are two abysses in the human soul: dead-end nothing, an infernal underground, and God’s heaven which has imprinted the image of the Lord.” The first abyss is atheistic; only that latter abyss is a Marian one.

A descent into the Tomb of the Virgin in Jerusalem, where this journey began, illustrates the cryptic utterings of the church’s myriad mystics. This chamber, along with its countless global siblings, tells us that that depth outpaces height. The Mary underground is an atlas of architectural humility, an international template of contemplative prayer. Where the once-proud above-ground churches have vanished, sometimes only the depths remain. I expect that in the eschaton, the same thing might be said of Christianity itself, not to mention our own biographies. Only the depths remain. Indeed, the Bible depicts the final judgment of God (which is what the word “Jehoshaphat” refers to) as a further deepening of the very valley where Mary’s tomb lies today (Zechariah 14:4). God’s work is frequently untraceable in proud skylines, undetectable to the keenest surface eye. Our regard is enticed by perceptible growth and measurable impact, but “he hath regarded the lowliness of his handmaiden” (Luke 1:48). This is a quiet wisdom that Christianity never ceases from shouting, a very public truth that somehow remains secret. So much so that I wonder whether I should have written about it here.