I

It was in the cowboy days of subprime mortgage lending and a bank was dumb enough to give me money to purchase a bungalow in Durham, North Carolina. I was a twenty-five-year-old graduate student in religion, and my husband and I had recently moved from Canada, where our credit scores were purely hypothetical and the meagre stipend that I received for teaching, researching, and correctly pronouncing Kierkegaard’s name to my classmates (no, look, it’s more like Kierkegore) had really only furnished us with friend-making stories about the time we got vitamin deficiencies and all the skin on my husband’s hands inexplicably peeled off. But we had a house we couldn’t afford, which was still a treat, and the previous owner had left not only a bright green mini-golf carpet in the living room but an entire Elvis Presley tribute in what later would become our guest room.

There was a shed in the backyard with all kinds of promise—a simple peaked structure that was two floors high and lined with thick white oak. It had been a carpenter’s workshop for the owner who had built the main house and even bothered to line the edges of the property with elegant masonry quarried from the same blueish gray stone that makes Duke University look like Duke University. But the problem with the shed was the crater, where the roof had sunk so low that termites and wet wood were threatening to pull the whole thing down. We tried to prop it up as best we could—beams here, brackets there—but the only real solution would be a religious one.

I have always believed that one of the great arguments for being part of a collectivist Christian tradition—three cheers for Mennonites, Hutterites, Amish, and Anabaptists of all kinds—is their willingness to do voluntary, gruelling manual labour and call it love. And we would need a lot of love. So our Mennonite family drove the thirty-seven hours from their prairie homes and took residence in the King of Rock and Roll’s Memorial Room and used reciprocating saws for most of the day until their biceps burned and not much of the original building was left. Then they measured new wood and we bought a nail gun, and sometimes, at night, I would wake up to find my husband flicking me in his sleep because his hand, the nail gun, had a lot of work left to do.

I have always believed that one of the great arguments for being part of a collectivist Christian tradition is their willingness to do voluntary, gruelling manual labour and call it love.

That year the star of the Christmas letter was the shed, with a few addenda to make clear that it should last another twenty-five years before it caved in again on account of the limited warranty on the shingles. I thought about this often when I would sit in the yard, watching the same people show up to build me a fence because I had recently received a sudden Stage IV cancer diagnosis and there was nothing else to do. I wondered about the shed, which would almost certainly outlive me now, and how all my plans (oh, my beautiful plans) had been stripped down to the studs.

Human lives seem like very sensible projects when you initially add them up. A golden anniversary is fifty years and possibly two kids and three furnaces. A retirement home for your parents is at least another monthly mortgage payment for a decade, but you can probably budget correctly if you imagine finally paying off your student loans. And then taking out another. We add and subtract for radiators and replacement cars, and when the dishwasher vomits all the soapy, dirty water onto the hardwood (only ever when we are on vacation), we don’t feel lucky, but we are.

What I had not learned from my shed caving in was what Simone de Beauvoir calls our “facticity.” All of our freedoms—our choices and our ridiculous attempts to plan our lives—are constrained by so many unchangeable details. I was born in this particular year to those parents in this town. This medication exists and that treatment doesn’t, but now it seems that all along I had these cancer cells in my colon, spreading to my liver, and scattered in my abdomen because of a genetic blueprint written long ago. This existential state is, to borrow a term from Martin Heidegger, the thrownness of human life. As we wake to the suffering of this world and our own existence, we find ourselves hurtling through time.

Even at my most durable, it took so many people to build my life, prop it up, and maintain it. But once I was sick, I came to realize that the most basic aspect of our shared humanity is our fragility. We all need shelter because we are soft and mushy and irritable in the elements—and we will need so much more than a bank loan because, sooner or later, we are left exposed. Time and chance, sayeth Ecclesiastes, happeneth to us all.

Frankly, none of us can afford the lives we already have. We set out to build our own dreams, slay our own dragons, and pay our own taxes and find that we trip over our health and our marriages and the way our inboxes suck us into the void. We were promised that American individualism and a multi-billion-dollar self-help industry would set us on our feet. When North Americans look for answers to our dependence, we often turn to the easy promises of the gospel of self-help. “Try harder!” “Change your mindset.” “You are your greatest hope.” We bought cheap paperbacks in a frenzy to find a cure for being human. But soon our own limited resolve—and the relative weakness of our institutions—conjured up the atomism that Alexis de Tocqueville so feared. Our dreams turned out to be built from toothpicks, each person propped up to stand entirely alone.

As we wake to the suffering of this world and our own existence, we find ourselves hurtling through time.

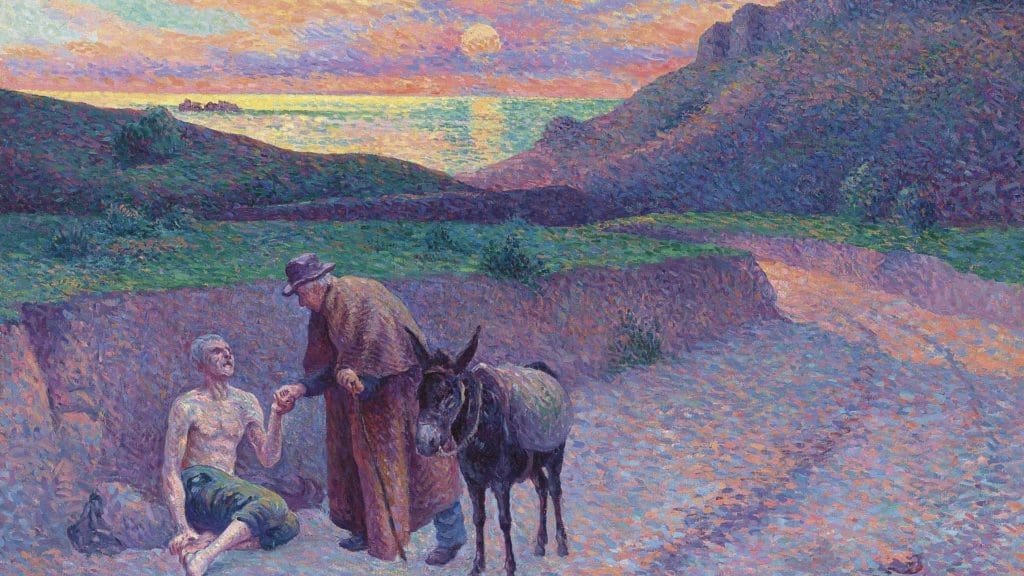

We understand instinctively that we cannot win this game of solitaire. Our churches and book clubs, Bible studies and farmers’ markets, carpools and sports teams offer little reminders that we should need each other, borrow and lend money, babysit and run an errand, argue and debate. “Absolute independence is a false ideal,” argued the sociologist Robert Bellah, whose trenchant understanding of the modern self rarely missed the mark. “It delivers not the autonomy it promises but loneliness and vulnerability instead.” But we usually only see this when we have sunk to the very bottom. Pastor Nadia Bolz-Weber describes how she understood the truth of interdependence most fully when she began practicing the uncomfortable honesty demanded by Alcoholics Anonymous. “Recovery is hard to do on your own. You have to do it with a group of other people who are messed up in the same way but have found some light in their darkness. Sitting in those rooms in 12-step meetings, there’s a particular kind of hope that only comes from being in the midst of people who have really suffered—suffered at their own hand—who can be completely and totally honest about that.” They nicknamed this sort of community “The Rowing Club.” They would have to take turns pulling on the oar. At times, each would have to be willing to be carried.

The English word “precarity” means a state of dangerous uncertainty, but its Latin root tells us a good deal more about its Christian character. The term comes from precarius, or “obtained by entreaty or prayer”—a state where we cannot achieve things by ourselves. We must rely on someone else, God or neighbour. But a letter to Dorothy Day from a priest in Martinique was quite pointed about what it would mean for people wanting stable roofs: “Here we want precarity in everything except the church. These last days our refectory was nearly collapsing,” he wrote. “We have put several supplemental poles and thus it will last, maybe two or three years more. Someday it will fall on our heads and that will be funny.” But he couldn’t bring himself to stop feeding people in the breadlines in order to be another kind of church, the kind that was “always building, and enlarging, and embellishing.” We have no right to, he concluded. No right, I suppose he meant, to demand security afforded to no one else. As Christians we must nod our heads and shrug our shoulders when we’re told, in no uncertain terms, that there are no lifetime warranties.

There is a tremendous opportunity here, now, for Christians to develop language and foster community around empathy, courage, and hope in the midst of this fear of our own vulnerability.

There is a tremendous opportunity here, now, for Christians to develop language and foster community around empathy, courage, and hope in the midst of this fear of our own vulnerability. Our neighbours are expressing an aching desire to feel less alone, needing language for the pain they’ve experienced, searching for meaning and someone to tell them the truth. They are hungry for honesty in the age of shellacked social media influencers. They are desperate for a thicker kind of hope that can withstand their circumstances and embolden them to preach the truth of our resurrected Lord whose future kingdom will have no tears and no pain and no Instagram at all.

We have a few good clues that we are allowed to hope for this kind of interreliance here, now. There’s a strange story in the Gospel of Luke about friends who bring one of their own to see Jesus. Their Rowing Club was a man down, so they carried him to where Jesus was preaching in hopes he could be healed from his paralysis. But the crowds were thick and they couldn’t get through the door, so they had a dangerous idea and climbed onto the roof and began to dismantle it. Then they lowered their friend through the tiles on a stretcher into the middle of the bewildered throng. And then, and then, and then, a miracle happened.

It is a miracle when we let ourselves, in desperation, be lowered into the unknown. When we let ourselves cry or scream or even whisper that we fear our own undoing. We will have almost nothing in our control except the knowledge of our fragility, and we watch someone else wear themselves out running to the pharmacist or cleaning the bathrooms and sanding a plank of wood for yet another Anabaptist form of love.

It is a miracle when we see the precarity of others and we decide to carry the weight of their stretchers instead of worrying about the groceries. God bless all the people who bothered with my complaints and worried about my heartbreak. The saints are those who press pause on louder concerns because they have decided to remember what they would rather forget: our independence is a sham.

And it would be the greatest miracle of all to be the paralyzed man who gets off the stretcher. Who hears Jesus’s voice returning us to ourselves. We are healed. We are whole. We came through the roof, but we walked out the door. Hallelujah.

If I am very lucky, the shingles will last and the chemotherapy will hold and love will continue to do most of the work. I will go back to being someone who tallies up the inconvenient expiry dates of large appliances and count on birthdays and New Year’s to set the clock of my mortality. I will be like the homeowner an hour after Jesus and the crowd have left, my floor littered with broken tiles and crumbled plaster. And I will look up, through the gaping hole to the blue, blue sky right from where I stand, no longer surprised by the fundamental Christian truth that the roof always, always, caves in.