L

In the beginning there was only the Prajapati. His word was with him. This word was his double.

—Tandya Maha Brahmana

For me there is a Christian Advaita (“non-duality”) in which the mysteries of faith are not lost but finally realized.

—Bede Griffiths

The “All-tree” of Paradise is the Word and Wisdom of the Father, Our Lord Jesus Christ.

—John Scottus Eriugena

An Upside-Down Tree

Long before I had any familiarity with Hinduism, I dreamed about an upside-down tree. Its roots reached into the heavens; its branches and polychromed leaves covered the earth. Nearly a year after the dream, I read the Kata Upanishad for the first time:

The tree of Eternity has its roots above

And its branches on earth below.

Its pure root is Brahman the immortal,

From whom all the worlds draw their life, and whom

None can transcend. For this Self [i.e., God] is supreme!

A Jungian would call this coincidence casual proof for the theory of the collective unconscious, while the more skeptical might say I must have encountered the motif somewhere along the way without realizing it, which my subconscious simply recycled. Or maybe no explanation is required at all, as there is nothing entirely surprising about dreaming of an everyday object upside down. But the dream had that numinous character, which for me rules out the skeptical approach. A deeper explanation may be that the dream signals the enduring power of a subcontinent’s devotional medley to which we assign the word “Hinduism,” a heritage that stretches back four thousand years, making even the Judeo-Christian tradition appear relatively young. Perhaps my dream signals that there is something universal about Bharat, the Sanskrit word for the nation more commonly called India, that is not of mere regional interest. Instead, India concerns all of humanity, insofar as to be human is to grapple with the mystery of God.

Whatever the explanation, the time for merely reading about India was over. Too many of my students were asking me questions about how to reconcile yoga with their Christian faith, and I knew my answers were bookish. For years my college had been assigning Shūsaku Endō’s Silence to freshmen. The brightest of them soon discovered his final novel, Deep River, which goes beyond Japan to grapple with the earlier religious mystery of India. The least I could do, as one entrusted to help students grapple not with the questions I expect they will have but with the ones that actually drive them, was to visit India myself, where—in the words of Jung—“there is no village or country road where that broad-branched tree cannot be found in whose shade the ego struggles for its own abolition, drowning the world of multiplicity in the All and All-Oneness.”

India concerns all of humanity, insofar as to be human is to grapple with the mystery of God.

Was I just one more American Dharma bum, disaffected by secularism, seeking spiritual asylum in India? I certainly met my share of such seekers on my journey, and I am well aware of the many ways romanticized Western notions of India are at odds with the reality of the country’s rapidly accelerating economy and its hopes to match the West. Still, I like to think that the terms of my visit as a Christian pilgrim were different. I was journeying to the India not only of Sankara and Ramana Maharshi but also of St. Thomas and Sundar Singh. Which is to say, my aim was to encounter Christian India as well as her more prominent Hindu counterpart. Still, I thought it best to begin my journey in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh, in the town that might be considered the Hindu Jerusalem, Varanasi on the Ganges. In Deep River, Endō’s Christianity—challenged to its limits by Hinduism—came into starkest relief in this city, one of the oldest in the world. “Older than history, older than tradition, older even than legend,” in the words of Mark Twain.

Gauging the Ganges

I arrived in the early morning and pushed through the streets, fending off requests for selfies, money, and autorickshaw rides. But what I thought were impossibly crowded thoroughfares, I soon discovered, was the early morning lull. As the day’s real traffic began, I jostled shoulder to shoulder with devotees and Dalits fighting for space to move. The late-June heat intensified, and I could find no break in the cityscape for the river I had come to see. Fortunately, my requests for directions were fruitless, for this predicament led to the singular urban surprise of my life. Upon turning one corner, relief from the pressure cooker of the streetscape coincided with my first view of the Ganges itself. As I pierced through the remaining throng, the river opened like a promise. A gentle haze eased the sun, softening my view of bathers and boats immersed in brown. A stretch of white, camel-strewn sand beyond the river completed the view. Maybe the water, which was once a congested mass of Himalayan snow, was feeling the same relief from the crowding as I was.

I had a few hours before I could check into my impossibly inexpensive Airbnb, and I sat down to pray. Ignoring everyone who asked for my photograph or funds was a remarkably practical exercise in what prayerful Christian meditation is in the first place—surrendering thought instead of engaging it. When my timer went off, thought reasserted itself. Why had I really come here? Thomas Merton answered the question in his Asian journal in this way: “To find something or someone who will help me advance in my own spiritual quest. . . . The great thing is to respond perfectly to God’s will in this providential opportunity, whatever it may bring.” Another answer came from Henri Le Saux, the French monk more widely known as Abhishiktananda (Bliss of the Triune God). After decades in India, having completely absorbed Hindu culture while remaining (some would say barely remaining) a Christian, he arrived at a different answer, the fruit of a lifetime of rigorous ascetic practice and prayer: “In this quest you run about everywhere, whereas the Grail is here, close at hand: you only have to open your eyes.” But India—for Merton, Abhishiktananda, and for me—provided necessary assistance in opening them.

Crowds gathering for an evening ceremony at Varanasi (all photos by author unless otherwise indicated).

India is abject squalor pierced with undeniable beauty—or is it the other way around? If tropes about the “Christ-haunted” regions of America are overplayed, they are ill-suited to India, where God’s presence is more visceral than any mere haunting implies. God is no ghost in India, for a ghost implies a presence that was more perceptible in the past. God is instead immediately available, a visceral fact as real as that ox straddling the median on the highway. Of course, God is immediate everywhere. Even Thomas Aquinas, the great Catholic scholastic, plainly insisted that “God is in all things.” But it’s easier to see and feel that fact in India, where poverty—or, to a lesser degree, the risks and uncertainties that come with travel—pushes human life to the edge of itself. At this edge, divinity is less easily ignored.

Sara Grant, a Catholic nun who was tutored by Iris Murdoch at Oxford and then devoted her life to India’s Christian ashram movement, puts it this way:

The Upanishadic outlook on the world is in marked contrast to that inherited by Western man from his Hebrew and Greek ancestors. In this tradition the universe is permeated by a supreme and creative sustaining Presence which is itself the sole ultimate Reality and is to be approached not by rising above the high places of the earth to some empyrean heaven, but rather by withdrawing into the depths of one’s own being, which is both thoroughly rooted in the earth, and yet ultimately also in the Eternal.

Perhaps this helps explain how, on a typical evening in Varanasi, all India seems to appear for bouts of riotous devotion on the ghats, those steeply inclined precipices that mediate between the city and the river itself, perhaps between earth and heaven as well. These gatherings have the energy of American summer music festivals like Lollapalooza, but unlike at our festivals, grandparents and grandchildren participate as well. Alcohol is both unavailable and unnecessary. Young brahmins lift candle contraptions resembling small Christmas trees over the Ganges in choreographed reverence. Music blared over a loudspeaker unifies the crowd in an energy that is both heaving and hospitable at once. On one of these celebrations, a sadhu (a Hindu holy man), dressed in orange and with skin covered completely in white ash, noticed I was more an observer than a participant, and he bopped me on the back with a decorated stick. When I turned to him, startled, he caught my eye and said “Boo!” with a smile. I got the message and tried to leave my inner observer behind.

An evening ceremony at Varanasi.

There are enough cell phones in use in contemporary Varanasi to confirm all the prophecies of smartphone doomsayers. Even the holy city of the Ganges, one of the oldest in the world, has succumbed to big tech. But this diagnosis would be too facile. To be sure, a solid half of the swelling crowds I witnessed did raise their phones to capture the experience. But one young brahmin penetrated the mass with his flaming lamp, giving individuals a chance to experience holy light directly. As he wove through the mass of humanity, cell phones were briefly pocketed, and viewers became participants again, lifting the smoke over their heads with both hands in a gesture of receptive reverence. Phone light was subordinated to candlelight. Technology was not condemned but transcended.

Many stay up all night or sleep along the ghats. I did so myself one evening when a train delay caused me to be locked out of my room. I felt far safer than I would have sleeping in the streets of any major American city. Even so, most people go to bed early in Varanasi, for the next auspicious time for celebration begins at about five in the morning. The sunrise is welcomed with a fresh line of young brahmins lifting up new contraptions of incense to worship the river again—or was it God’s presence in the river that they worshipped? “Forgive me, O Shiva, for three great sins,” reads a prayer attributed to the Hindu sage Sankara. “I came on a pilgrimage . . . forgetting that you are omnipresent; in thinking about you, I forgot that you are beyond thought; in praying to you, I forgot that you are beyond words.” Fortunately, I was aware that the same depths are on offer in the Christian apophatic tradition as well, from Dionysius the Areopagite to Evelyn Underhill.

Ignoring my guidebook’s suggestion to join a tourist boat to witness this morning devotion, I decided to take the public boat instead. I was rewarded by an impromptu introduction to Hinduism given to me freely by a traditionally dressed Indian woman, probably in her thirties, travelling with her mother. She was a convincing evangelist. “Unlike Buddhism,” she explained to me as we floated through the rich, brown water, “Hinduism is not about dropping everything. It is about love. I feel loved so much.” Then, as if intuiting my need to distinguish my Christian faith from her own, she added, “I must have done something good to merit this affection from God.” I offered no counter-lecture on the doctrine of grace, but I did permit myself a smile.

An early morning ceremony at Varanasi.

To my question as to which god or goddess she felt most loved by, my guide gave the immediate answer of Krishna—quite a statement in the city of Varanasi, so sacred to Shiva. “I love Krishna dearly, and I am loved by him,” she reasserted with an irenic smile. After treating her homebound children and husband to a video visit of the ghats through her phone, my guide resumed her tutorial. To my questions about Kali’s severity she replied with a firm, even urgent correction. “Kali is kind,” she told me. “Her anger is only directed to our illusions.” My guide told me her piety was grounded by her practice of yoga, which tethered her both to the earth and to her body. “One day,” she assured me, almost in a whisper, “Krishna and I will become one. I know it.”

This positive encounter contrasted with less pleasant ones. The young men who attempted to initiate me into the complexities of Shivite worship, only to extract a donation. The unsolicited tour guide who expertly dodged my initial refusals and then used the site of dying people preparing for cremation, as well as the burning bodies themselves, as an attempt to get money. The impatient Brahman priest who snatched a supplicant’s offering, tossing it onto the river of milk descending on the phallic lingam, only to then shove the pilgrims rudely along. But my boat tutor’s kindness eclipsed all such incidents. And at least the lingam, as Merton enjoyed pointing out, is more sophisticated than the erotic poetry of D.H. Lawrence. Rather than scanning the city for weak points to confirm my own Christianity, it might be better to heed the counsel of Count Hermann Keyserling (1880–1946): “Every would-be Christian priest would do well to sacrifice a year of his theological studies in order to spend this time on the Ganges: here he would discover what piety means.”

At Varanasi, it became clear to me that India is a world without Theodosius. If this Christian emperor banned paganism in AD 392, no such edict was issued in India. Shrines persist on holy hills and street corners to every god and goddess, often competing with Christian churches. Because the doctrine of recompense by reincarnation has its downsides, most honest observers would admit that Christianity surpasses Hinduism in its treatment of the poor. A question nevertheless presents itself: Can Christianity, still less than 3 percent of the population in India, really compete? To ask this question in the north would give Hinduism an unfair advantage. So, after visits to Buddhist sites at Bodh Gaya, I made my way to the best places in the world to ask about India and Christianity—Christian ashrams. Unlike Hindu ashrams, these places are centered not on a living Hindu guru but on the risen Christ. I needed to spend time with those who were answering the question of Christianity’s relevance to India not only with their essays but with their lives.

Heading South

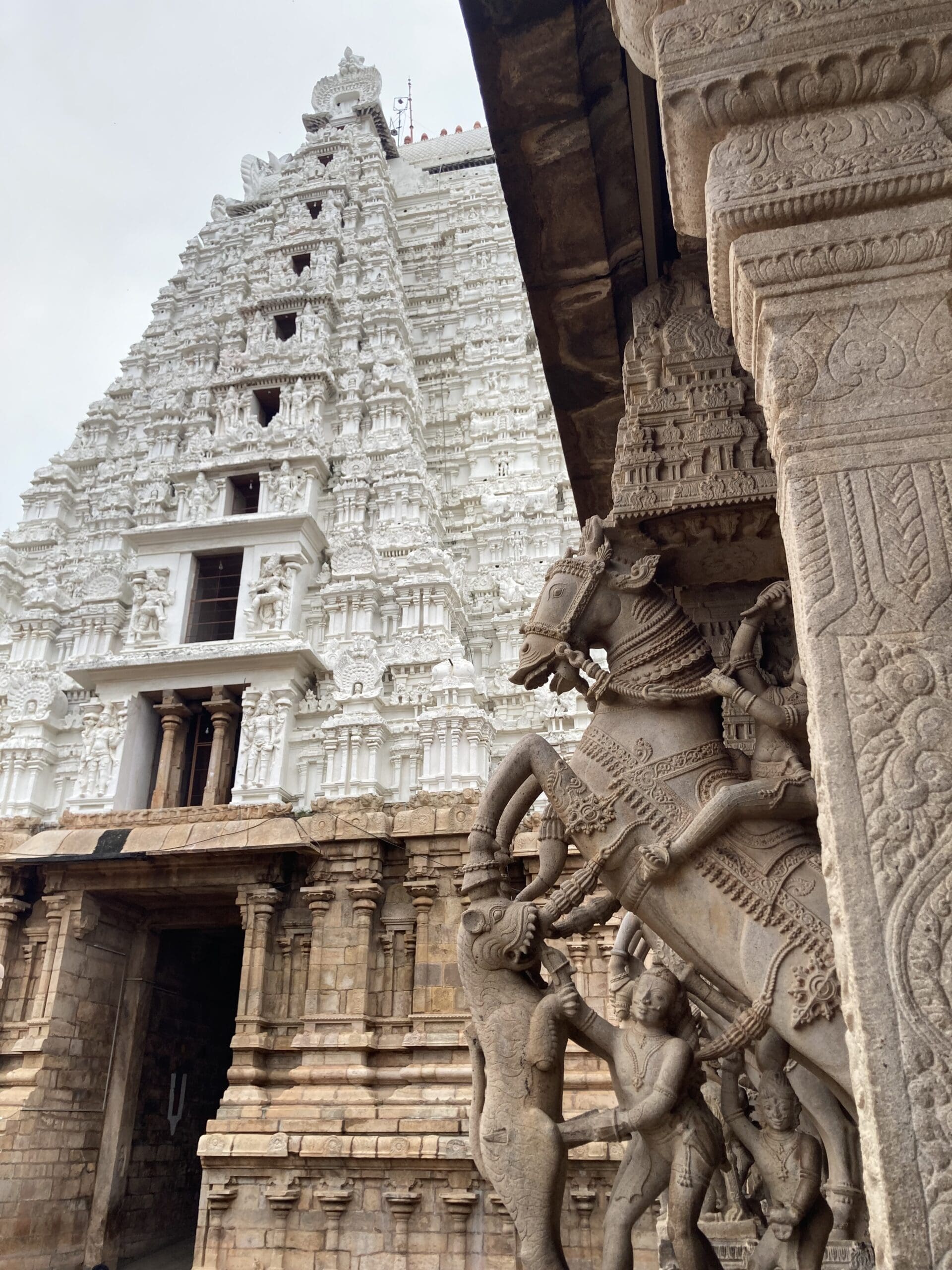

The first of the Christian ashrams was Christukula (Family of Christ) Ashram in Tirupattur, which was launched in 1921 by two Anglican doctors, an Indian and an Englishman, who had met in England. They were inspired by both Roberto de Nobili and Sundar Singh, who had earlier experimented in radically Indianized Christianity. On my visit to Christukula, I feared such devotion would have waned a century since the ashram’s founding, but I arrived in the middle of a prayer meeting and was welcomed like a long-lost brother. The ashram now sponsors a thriving adjacent medical center and school. The pastor had me ring the tower bell, and as it resounded, he told me that the area villagers know that prayer is answered here in the name of Christ. Christukula’s towering white gopuram, crested by a cross, continues to be a daring reply to the Hindu temples that surround it.

But if Protestants launched the ashram experiment, it is primarily (though not exclusively) Catholics who keep them going today. You might say that the glory days were not those of Bede Griffiths and Henri Le Saux, but that now is the time to visit such places. It is a mark of the success of these experiments that they are now run completely by Indians. If one is going to accuse these ashrams of appropriating Hinduism (a common, if tiresome, charge), one must take it up not with Westerners but with Indians themselves.

Likewise, if one is going to say that Christianity is somehow less than Indian, one must contend with the St. Thomas tradition, which is roughly as old as Christianity itself. Lore has it that the apostle Thomas brought the gospel to India, whereupon the man who put his finger into Christ’s lance-pierced side was martyred, on a hill now near the airport in present-day Chennai, with a lance himself. My first morning liturgy in the most famous of the Catholic ashrams, Saccidananda Ashram Shantivanam, in fact, was on Thomas’s feast day. I took this as a sign that my quest for a Christian expression of India’s religious genius might actually succeed.

Shantivanam means “forest of peace.” And a forest it is, of banana and bodhi trees interspersed with parrots and peacocks on the banks of a different sacred river—not the Ganges but the Kaveri. It is also known as Saccidananda, the Ashram of the Holy Trinity. The bold gesture of interpreting Saccidananda—the famous Sanskrit word for ultimate reality (being, consciousness, bliss)—through the lens of the Holy Trinity, is the kind of swagger that has long marked this Christian experiment. It was established in 1950 by two French founders, Henri Le Saux (the aforementioned Abhishiktananda) and Jules Monchanin. They were later followed by C.S. Lewis’s charismatic student Bede Griffiths, a British Benedictine monk who came to India, as he famously put it, “to find the other half of my soul.”

Silence was the primary agent in every liturgy of Shantivanam, a silence that made the reverent speech and the rhythmic songs all the richer. The om that I heard in the Hindu temples was here woven into the Christian liturgy.

When I entered the darkened interior of the domed church, some of the monks were already an hour into silent meditation before the liturgy began. Silence was the primary agent in every liturgy of Shantivanam, a silence that made the reverent speech and the rhythmic songs all the richer. The om that I heard in the Hindu temples was here woven into the Christian liturgy, lending it a distinct regional resonance. “Om is not a name for God,” wrote Abhishiktananda, who is now buried next to the church. “It stands for the ineffable and unsearchable nature of the abyss of divine being. . . . The one who had been initiated into the Indian tradition, and above all if he has accepted the Gospel message in its fullness, has as much right as his Hindu brother to murmur the Om.”

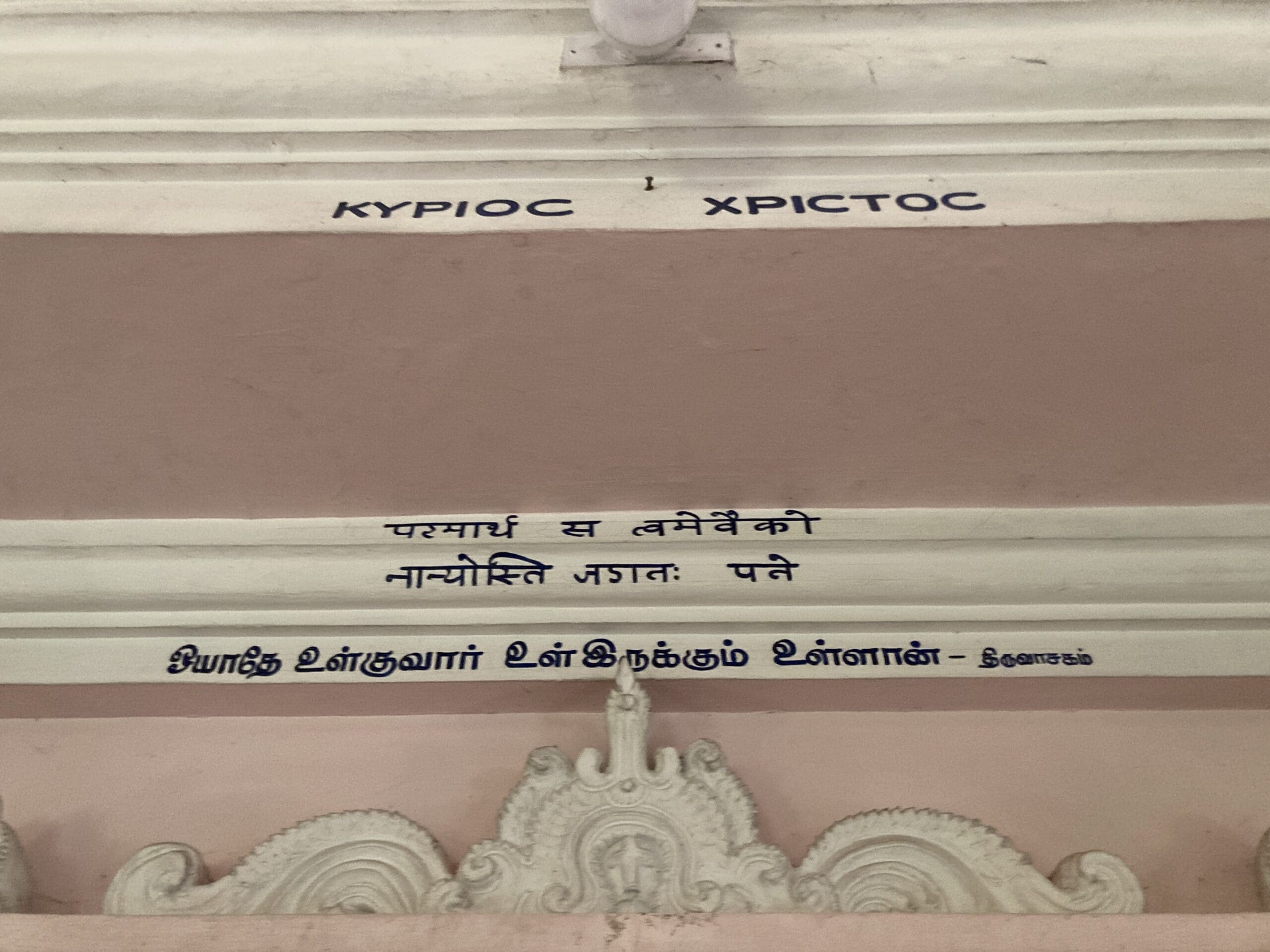

The circular waving of a candle in front of statues of gods and goddesses that I witnessed in Hindu temples, a gesture known as arti, took place in this Christian setting as well. But the gods and goddesses were replaced with the Eucharist. Other features of Hindu worship were also Christianized here, including the imposition of ashes and the third red eye of non-duality, which one gently dabs on one’s forehead after prayers. After the liturgy, I examined the cave-like inner sanctum of this temple where the Eucharist is reserved. Words from the Upanishads were inscribed just above the sanctum in Sanskrit (“You alone are the Supreme Being; there is no other Lord of the world”), and prominently above them were the words “Lord Christ” in Greek. Whether or not the exterior of the church looks like a cake (as some have suggested), it is an indigenous form of colourful sculpture, resembling the Hindu temples less than a mile away. Vishnu is here fulfilled by Christ; Parvati is fulfilled by a Virgin Mary; and the fantastic animal sculptures that bedeck Hindu temples are fulfilled by the angel of Matthew, the lion of Mark, the ox of Luke, and the eagle of John.

Inscriptions above the sanctuary at Shantivanam.

Some fundamentalist Hindus are infuriated by these forms of Indian liturgy and architecture employed in the worship of Christ. These same Hindus find the Western architectural forms in India infuriating as well, insisting that Gothic towers and white faces betray the face of a foreign, imperialist faith. These twin despisals in fact betray the extreme Hindus’ desire for Christianity to disappear no matter what form it takes, and some of them would not stop at violence to realize this end. But the Christian ashram experiment happily continues, and the monks and nuns of this community are spared the fate of St. Thomas, for now. Shantivanam, which has long been grafted into the Camaldolese strain of Benedictine monasticism (a strain that allows more time for private contemplative prayer), just last year even attained the status of an autonomous house, testifying that they are no longer simply an “experiment” but an enduring fact.

From my conversations with the monks at Shantivanam, I detected not a uniform theological outlook but thoughtful ferment born from deep experience. The Hindu insight of non-duality is fashionable in advanced Christian theological discussions of late. David Bentley Hart, for example, frequently appeals to the Vedas and bookended his publication You Are Gods with epigraphic Sanskrit clips. Such a unitive vision promises deliverance from bifurcated Western categories that overplay the separation of nature and grace. While I applaud this maneuver, here at Shantivanam non-duality is not a theological appeal but a birthright. In his book Fully Human, Fully Divine, one of the brothers, John Martin Sahajananda, summarizes the wide-ranging discussions about non-duality over the centuries in Indian thought: there was the above-mentioned Sankara (eighth century), who preached pure non-duality (advaita); Ramanuja, who offered qualified non-duality (vishishtadavaita); and Madhva, who promoted a duality (dvaita) that many would see as more compatible with Christian and Jewish thought, where Creator and creation remain distinct. What makes Jesus original, according to John Martin, is that he did not choose between these schools but encapsulated all three: Sankara (“the Father and I are one”), Ramanuja (“I am in the Father and the Father is in me”), and Madhva (“my Father is greater than I”).

In his writings, John Martin leavens the gospel with the principles of non-duality but offers no slapdash equation of the soul with God. “The ‘I’ which says ‘God and I are one,’” he insists, “is not an individual ‘I’ or collective ‘I’ or universal ‘I’ but it is the divine ‘I.’” Offering a Christian commentary on the famous Hindu formula “Atman [i.e., the soul] is Brahman,” John Martin insists, “It is God [not the individual ego] who says I am Brahman.” I might not be willing to follow John Martin to all the radical conclusions that result from his Indianized Christianity, but one thing is clear: it is fathoms deeper than Eat, Pray, Love.

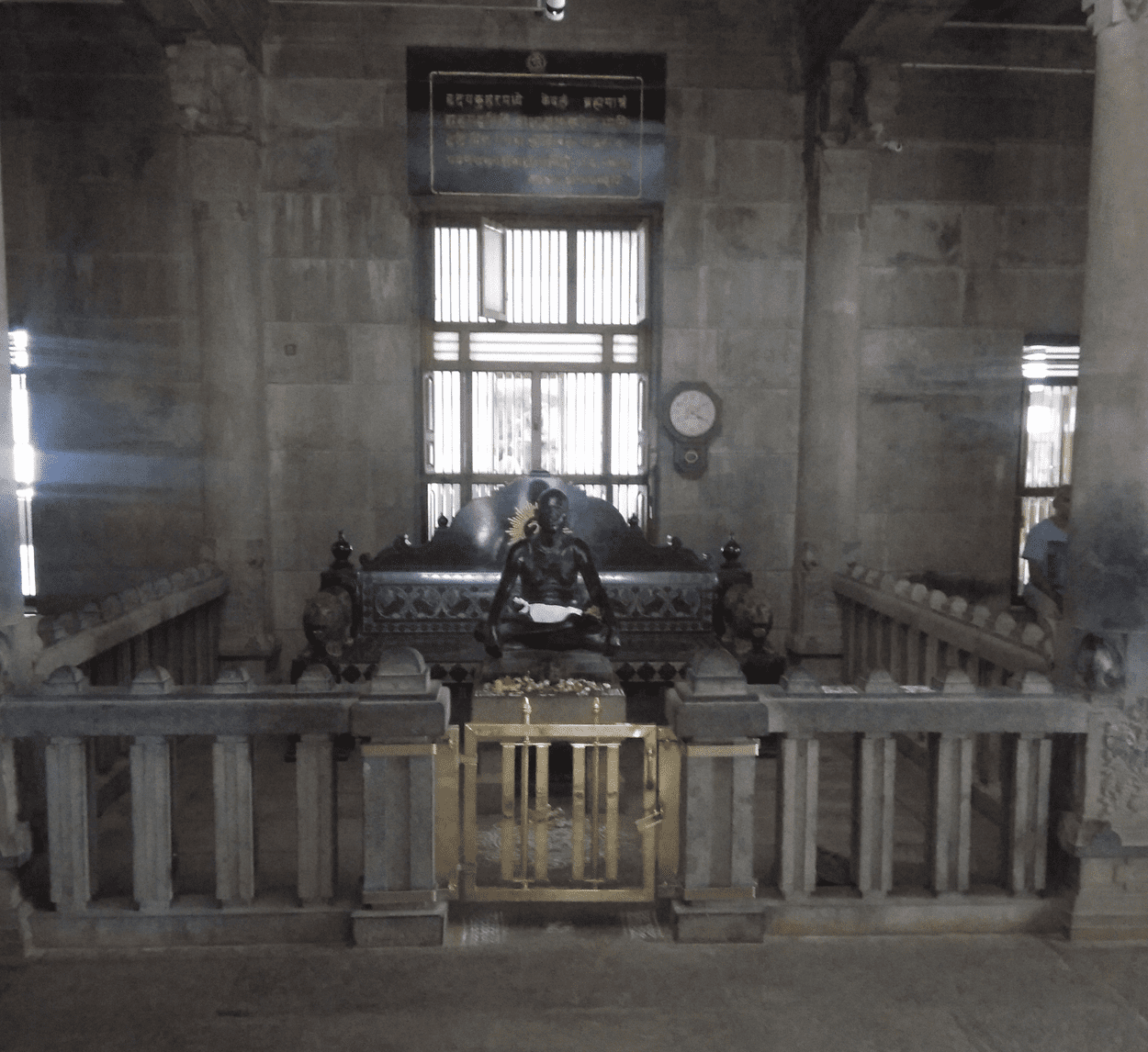

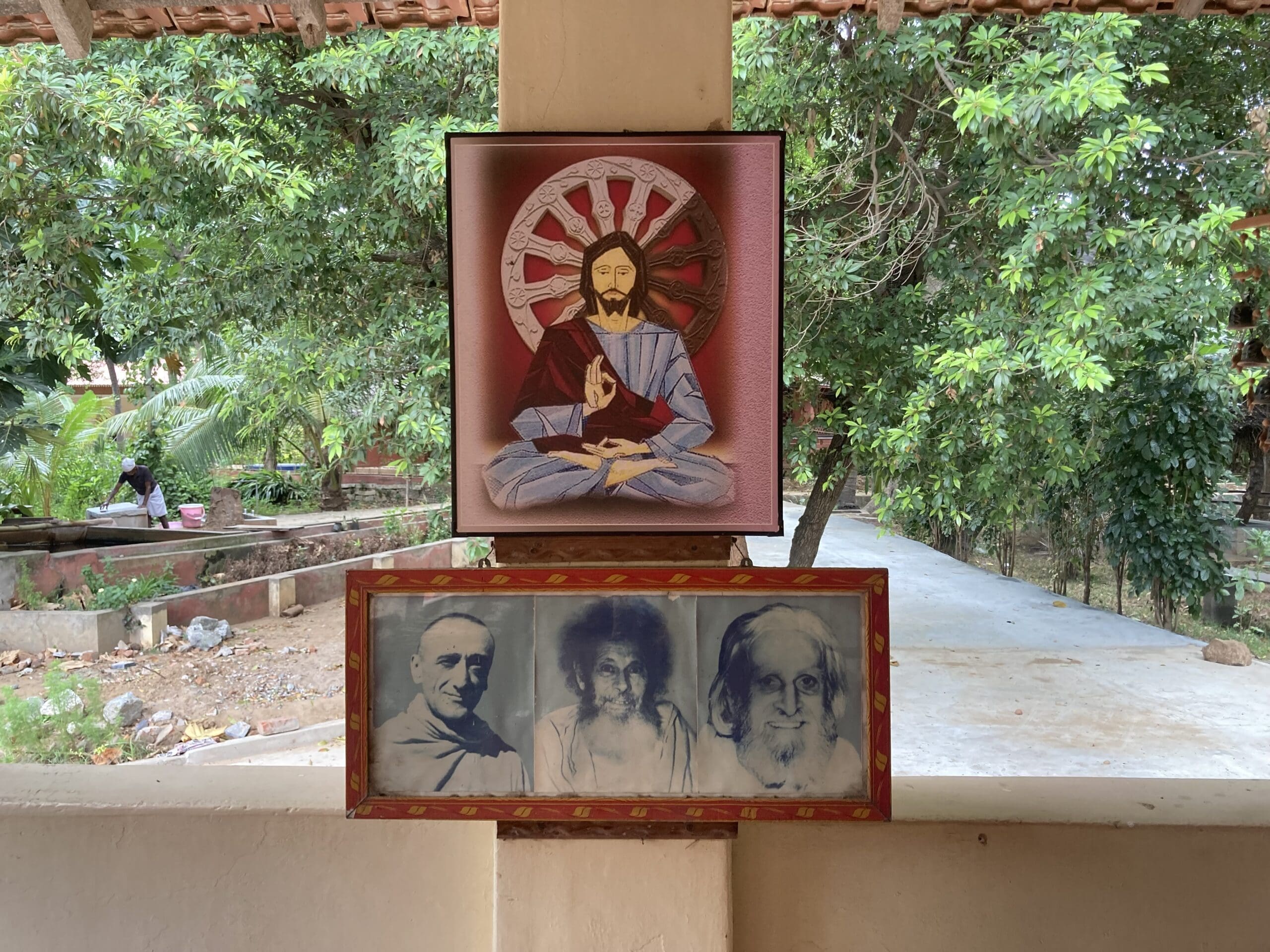

The Indian Catholics who now run Shantivanam have picked up where the European founders concluded, and they’ve learned some lessons along the way. One of the monks told me that even if a Christian ashram must be centred on Jesus, the late Bede Griffiths had (somewhat unwillingly) become a guru. This monk described to me Griffiths’s foibles without in any way maligning his character. The lesson was clear: keeping Jesus Christ, and not some other personality, at the centre takes serious work—the work of shunning celebrity and getting out of the way. This is the kind of labour that the current monks of Shantivanam seem eager to undertake. This insight, moreover, is materially expressed. It is fascinating to compare the marble statue of the guru Ramana Maharshi (1879–1950) at his ashram in Tiruvannamalai, swarming with meditating Westerners, with the similar marble statue at Shantivanam of Jesus the guru, in the lotus pose of course.

Christians make visits to monasteries for spiritual counsel, and on this score I was not disappointed. I enjoyed guidance from one of the hermits of Shantivanam, who gave generously of his time. “The aim of Shantivanam is to make Christian mystics,” he told me. The hermit was well versed in psychology, up to date on complex Jungian techniques of dream analysis. But one day a voice said to him, “Go beyond psychology.” By transcending without ignoring psychological issues, he entered more deeply into the mystery of God. “It helps,” he added, “that in India, unlike the West, psychology, theology, and philosophy are one.”

I was able to test these insights not only with Christian monks but with Hindu brahmins themselves in the massive, sprawling temples of South India. Entering their precincts felt, in a way, closer to visiting the original temple of Jerusalem than visiting the Temple Mount in Jerusalem today. For in Hindu temples the sacrifices are ongoing (including animal sacrifice during festival seasons). On one visit to the thousand-year-old Brihadisvara Temple, I conversed at length with an emaciated brahmin who spoke to me in perfect English. In a piece of advice that might have been given to someone about to undergo an acid trip, he told me the temple will respond to me with the attitude with which I approach it. If I approach the temple as a site of idolatry, that is how it will appear to me. If I approach it instead as a microcosm of the human body, as a testimony that I too am divine, it can become that for me as well. He concluded by offering me a prophecy: “Life will be fruitful and colourful for your entire family; many will salute you in the land of Illinois. I sense this. Shiva told me to tell you this.” I smiled and gave him the few hundred rupees that he was expecting in gratitude for our conversation. What a marked contrast, I thought to myself, to that other temple dweller, Simeon, who once said to the Virgin Mary, “A sword will pierce your soul too.”

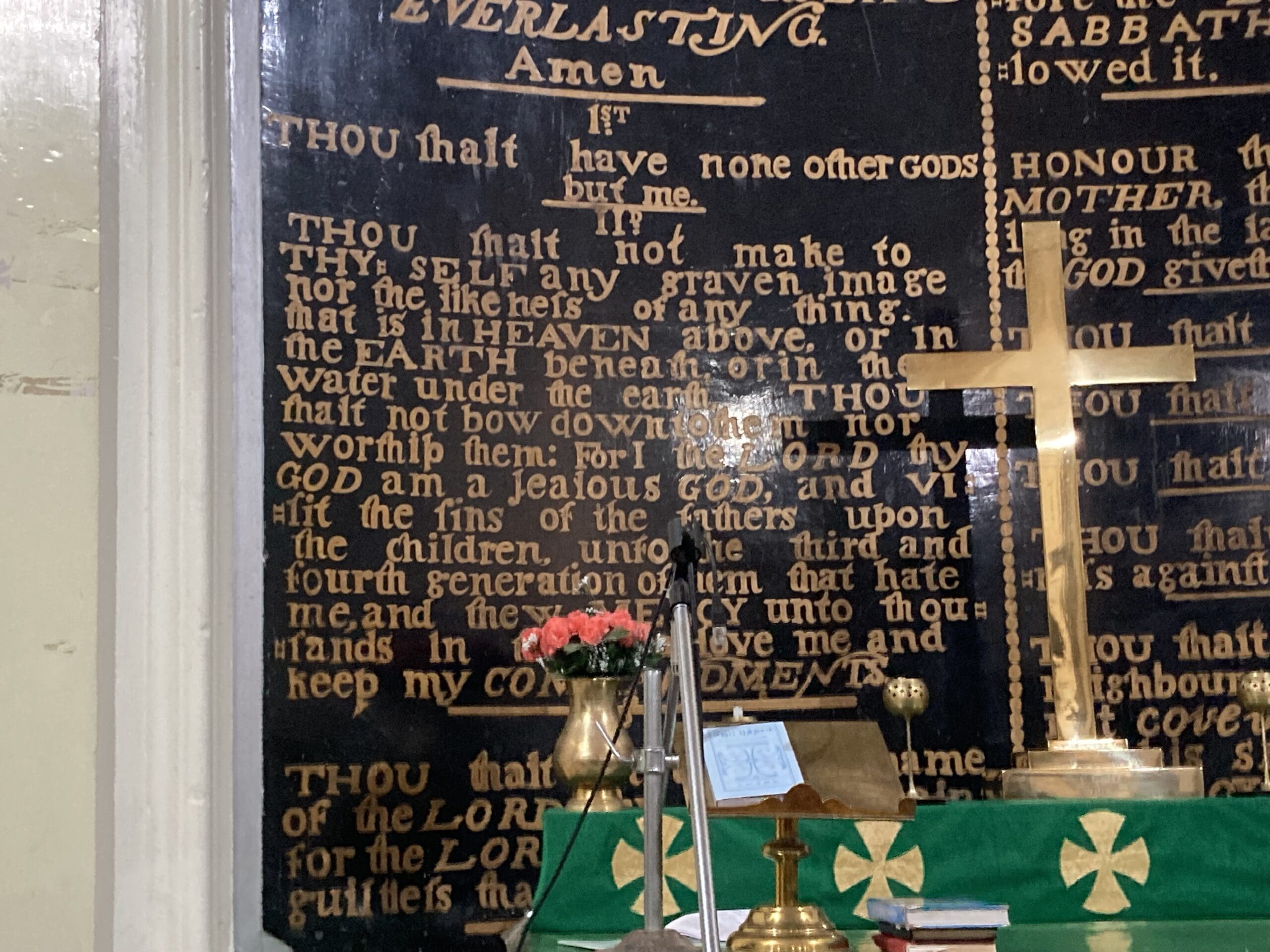

As much as I found the conversation refreshing, I was reaching my limit. On my departure from Brihadisvara, I made my way to an adjacent Anglican church just beyond the temple, where the standard printing of the Ten Commandments behind the high altar went out of its way to emphasize the words “Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image.” Earlier in my journey in India I might have found this assertion unnecessarily aggressive, but now with dozens of temple visits under my belt, I was freshly reminded that the Decalogue is no dualistic delusion. I recalled the words from Joshua read aloud one morning at Shantivanam: “Choose this day whom you will serve.” Eyeing more of the poverty-wracked beggars around me, I found myself adding a proviso to Hinduism’s proud claim: Sure, everyone may be God in India . . . but some are more God than others. When I asked if I could meet a living Hindu guru, I was saddened, but not surprised, to learn that several of them, such as Asaram, had recently been imprisoned for rape.

Jesus Purusha

Even so, back at Shantivanam, I couldn’t shake the fact that there was something of an equivalent to the famous Upanishadic utterance tat tvam asi, “Thou art that” (a variation on “Atman is Brahman”), in the Pauline declaration of justification by faith, where Christ’s righteousness becomes our own. Over and over, the rishis, those ancient and modern sages of non-duality, insist that the only thing keeping one from enlightenment is our ignorance. “Realization,” Ramana Maharshi flatly insisted, “consists only in getting rid of the false idea that one is not realized.” Is this similar to what the apostle is getting that when he insists in Romans 5:1, “Since we have been justified through faith, we have peace with God through the Lord Jesus Christ”? The Pauline difference, of course, is that justification comes to us through Christ’s crucifixion and resurrection. Perhaps this does not so much refute Maharshi’s insight as rescue it, laying it on a sturdier foundation, a foundation that makes much more sense of an undeniably sinful world. This distinction between Hinduism and Christianity might prompt howls of protest from Western advocates of the perennial philosophy, who believe all traditions at their best merge into one underlying mystical truth. But another realized Indian guru, Ramakrishna (1836–1886), appears to discern Christianity’s uniqueness himself. “Behold the Christ, who suffered a sea of anguish for the love of man,” he insisted. “It is he, the Master Yogi who is eternally in union with God. It is Jesus, love incarnate.” It is surely an irony that while many Westerners—from Somerset Maugham to the Beatles—have rushed past Christianity for the meditation-retreat circuit in India, Ramakrishna himself reverently burned incense before an image of Christ every day.

Saying that India’s greatest sages honoured Christianity is not to suggest that Christianity, to become fully itself, has no need for India. The monks at Shantivanam tell me that the answer to troubles that afflict American Christianity will not come by a grand theological synthesis but by experience. India (in the words of Abhishiktananda) urges Christianity “to an even more inward penetration of those depths, as yet unknown, of the unfathomable mystery which she carries in her breast.” What the same French monk called “the advaitan rope” can “draw water from the well of Christian experience, for the Church of the West must deepen itself.” The monks who run Shantivanam today are more stable and settled than the Frenchman and are—it appears to me at least—more skilled at handling the rope. As my hermit friend put it, “What matters above all is to move from the egocentric to the theocentric life.”

Shantivanam’s gentle and unassuming prior, Father Dorathik, gave me an impromptu lesson in Christian yoga, which is a perfectly natural combination for those who believe in an incarnate God. (It is a shame that North American Christians are not more aware of the publications, inspired at Shantivanam, like Thomas Matus’s Yoga and the Jesus Prayer.) There are sisters at Shantivanam as well, who live in an adjacent ashram just across the street. Though my conversations with them were more limited, their kindness and humour betrayed that they had accessed the same depths. They too joined us for three services of daily worship. I’ll betray my snobbery by insisting that the daily chants of these monks and nuns in Sanskrit and Tamil, as transfixing as the chanting of the monks of Mount Athos, are vastly superior to the electric-guitar-led praise bands in mainstream Indian churches.

Sara Grant illuminates here again:

The Hindu gods, then, are not historical figures, but projections of the Hindu psyche under the impact of profound religious experience of that supreme Mystery which illumines everyone born into this world, of which the historically conditioned humanity of Jesus of Nazareth is the authentic and tangible self-communication.

Is this what my guide on the Ganges tasted in her sense of Krishna’s love? I have little difficulty believing this. “The divine person [who is] Jesus is not exhausted by that historical appearance,” wrote Avery Cardinal Dulles. “The symbols and myths of other religions may point to the one who Christians recognize as the Christ.”

I therefore did not jettison my theological education in India, plunging into the abyss of advaita. Instead, I found myself more grateful for it than ever before. Karl Barth taught me that there is no human set apart from Jesus Christ. All people are contained in him, whether they realize it or not. “In him was life, and that life was the light of all humankind” (John 1:4). There is strange confirmation of this insight in the Vedas themselves—namely, in the Purusha Sukta, which proclaims there to be a cosmic, personal principle (Purusha) holding the universe and all of humanity together. As Ian Davie puts it in his remarkable book Jesus Purusha,

In Jesus Purusha we have the direct expression of deity, its express image, and in ourselves its indirect expression. . . . “Jesus is Purusha” constitutes the Hindu Gospel, and “Jesus is the Christ” the Palestinian, the inclusive Gospel is the proclamation of Purusha-Jesus-Christ. But the Hindu Gospel does not add to the fullness of the Gospel that has already been delivered to the Church: what it does is to correct an imbalance which is absent from the primitive Gospel, but which has developed over the past two thousand years because the Gospel has been interpreted almost exclusively through Western thought forms.

Into the Depths

Still, I had to go deeper into India, literally. A visit to Shantivanam is not complete without the journey north to Arunachala, the sacred mountain made famous by Ramana Maharshi that also beckoned Abhishiktananda. I ascended it barefoot. (Not by choice, but because I had to leave my shoes at the entrance, and how I wish I could have kept them.) But I was less adept at climbing than the equally shoeless monkeys who accompanied me, and my feet were bleeding by the time I completed the ascent. Only the caves offered relief from the heat. These were the same caves into whose depths Abhishiktananda absconded to confect the Eucharist. Maybe it was my exhaustion, but I cannot deny a powerful sense emanating from and through the caves as well. Yet the oneness I felt with those meditating with me, and even with the mountain itself, was not a vague, generic oneness. It came from the fact that all humans are united in Jesus Purusha, the Christ, his feet bleeding as well.

The view of Arunachaleswarar Temple from the caves of the sacred mountain of Arunachala.

But even if my Christian faith is intact after visiting India, I’m not entirely sure that I am. The word for what has undone me is, I suppose, advaita, non-duality, even if my hermit friend insisted on just calling this mystery love. Take the ultimate Christian “non-dual” claim, Jesus’s words “I and the Father are one.” One can resist this truth or dispute it or analyze it or dissect it. As a believing Christian, I had accepted that truth about Christ and observed it, as it were, from a distance, for Jesus uttered it about himself. But my experience in India led me to a deeper level still.

By “deeper level” I do not mean to claim that “I and the Father are one” is true of me in the same way it is true of Christ. That is the Hindu approach, and even if it is in theory open to all, Hindus themselves admit it is fully realized only by few (with many fraudulent claimants along the way). My approach is quite different. Having read the Christian mystics, I could certainly allow for the fact that Christ could say “I and the Father are one” through and in me. What I had not fully considered, however, was that if I were to allow him to do so, the truth of oneness would envelop whatever is left of my separate identity so that only that truth of oneness would remain. Then the truth is not disputed, analyzed, or even experienced. It simply is. “It is like rain falling into a river or pool; there is nothing but water,” wrote Teresa of Ávila. Or as Radiohead once put it: “For a minute there, I lost myself.”

“The aim of Shantivanam is to make Christian mystics,” he told me.

Words, images, and even music fail here, but this reality might be considered a Christian equivalent of nirvana. If Buddhists describe nirvana as a drop of water falling into the ocean, I am fond of Cynthia Bourgeault’s Christian inversion of this equation: not the drop in the ocean, but the ocean in the drop. Martin Laird, riffing off one of Augustine’s analogies in Confessions, puts it this way: “The sponge looks within and sees only the ocean of God. The sponge looks without and sees only the ocean of God, but not all of the ocean of God is within the sponge.” If this all seems excessively hydraulic, it must be remembered, as Bruno Barnhart argued, that Christian non-duality is irreducibly baptismal.

But when that is too much for the heavily conditioned sponge I call “me” to handle (which it most certainly is), there is no problem in heading back up to the shallows to surface for air, for the grace of Christian advaita is that it allows separateness to be true as well. Still, once one has tasted the oneness, any return to separateness is bound to disappoint. I think this was what my interlocutors at Shantivanam, in all their interventions, were trying to tell me. This “not-two-ness” is a quality of consciousness that must break into the world, and into the church. It is remarkably easy for the ego to clothe itself in Christian trappings, shrouding itself in theologically discursive drapery while remaining, on a deeper level, completely unchanged. This is the costume that India so effectively unravels. Thomas may have brought the gospel to India, but India helps bring the same gospel back, this time with its hitherto slumbering aspects, its deepest mystical dimensions, freshly stirred.

While in India, my conditioned Western ego had great difficulty hearing this message, so it entered my ear in another way. As I was reading in my cell at Shantivanam, a large Indian jumping ant crawled into my ear. Like a seasoned contemplative, I panicked, trying but failing to get it out on my own, even with tweezers. I ran to the Indian villagers who keep the ashram running, gesturing frantically to my ear, and they just kindly laughed. Then they urged me to bow my head, against my initial protestations, under a water pump. They filled my ear with water, and when I stood up again, out came the ant. Likewise, I had to humble myself before the traditional wisdom of India—which is a Christian wisdom—submitting myself to the baptismal mystery all over again.

Perhaps this is what Abhishiktananda meant when he said,

What India essentially needs are contemplative Christian souls who are ready to plunge into the depths of mystical experience, to lose their foothold, to disappear in it from human sight, trusting in the grace of the Lord who will enable them to bring to light the marvelous pearl of Saccidananda which the Spirit has hidden and sustained there.

For now India, thanks to the faithful monks and nuns of Shantivanam, still has this to offer.

Back to the Surface

All this having been said, it is still fair to ask whether it would have been better if Abhishiktananda had maintained his foothold. True advaita “blows up the institutional Church,” the French monk boasted near the end of this life. Bernard McGinn, after a lifetime of defending suspect mystics from hasty charges of heresy, deemed Abhishiktananda “beyond recognizable Christianity.” Abhishiktananda’s fans celebrate this fact, with a curious dogmatism, as the necessary endpoint of serious exploration of non-duality. But if non-duality is about oneness with everything, why this lingering animus toward institutions? It seems that those who discover Christian theological negation have yet to discover a deeper negation still, Meister Eckhart’s negatio negationis, the negation of negation, which lands one right back into the arms of the imperfect, insufferable, indispensable institutional church.

Notwithstanding his foibles, Bede Griffiths strikes me as far more dependable than Abhishiktananda. “The key to a Christian advaita,” Griffiths wrote, “is the experience of a differentiation within the Godhead itself [i.e., the Trinity] which grounds diversity in creation.” Jules Monchanin, probably the most theologically gifted of the three founders, also inspires more confidence than Abhishiktananda, whom St. Benedict himself might have considered something of a gyrovague. Monchanin developed a “growing horror at the forms of muddled thinking in this ‘beyond’ thought which most often proves to be only a falling short of thought, in which everything gets drowned.” Monchanin, who influenced the Western church through his friendship with Henri de Lubac, insisted that the purification of the cross is necessary if advaita and trinitarian thought—a mystically infused thought—are to responsibly coexist.

Monchanin died believing that his vision of Indian monks taking up his experiment would never come to pass. Yet now it has. The contemporary Indians who run Shantivanam today represent the fulfillment of his dream. They seek to expand on the gifts of the founders: the clarity of Bede Griffiths, the adventurousness of Abhishiktananda, and the theological rigour of Jules Monchanin. As one of the unassumingly peaceful monks put it (through a simple sign on the door of his hermitage), “We have come here to awaken from the illusion of our own separateness.” And yet that same monk, born on the feast of St. Thomas, preaches the cross, not just generic contemplation, as the way of awakening. If there really is no separateness, I slowly came to realize after nearly a month in India, then Shūsaku Endō is right. If Christ is in all things, then Jesus in some mysterious way is the Ganges, “accepting all, rejecting neither the ugliest . . . nor the filthiest,” and the upside-down tree I saw in my dream is the tree of the cross.