A

Audrey Watters is a prophet. Prophets aren’t fortune tellers, however. The main business of prophets, even in the Bible, isn’t the future. It’s the present. Better to say: it’s the set of possible futures that are liable to follow from crucial choices made in the present. Israel’s prophets brought a word from God to the people of God, and that word was—as it always is for prophets, including Jesus—repent. To repent means to turn, to veer right rather than left, to take this branch on the decision tree, not that one, to see the fork in the road for what it is: an opportunity, probably the last, to avoid disaster. Because disaster is what awaits if you continue on the current path.

True, Watters is a secular prophet. She doesn’t speak on God’s behalf or for the sake of a chosen people. But like Amos, she brings a word of judgment to the powers that be. Those powers she calls Ed Tech. And like the nations against which Amos railed, Ed Tech is a bastion of avarice and injustice. It grinds the faces of the poor into the dust.

Ed Tech is short for education technology. Think Zoom, “learning management systems,” online anti-cheating software. At first glance those might seem harmless enough. Allow Watters to dissuade you. She has a decade’s worth of work with which to do so. Sometimes it seems she has the beat all to herself, a one-woman journalistic gadfly buzzing around the behemoths and motherships of Silicon Valley. Unswattable, she maintains a blog, Hack Education, and has self-published several collections of talks and essays. In August MIT Press published her latest book, Teaching Machines: The History of Personalized Learning, which she wrote as part of a fellowship at Columbia University.

Teaching Machines recounts the creation and development of machines intended to complement or replace the education of children by living, human teachers in the classroom. (“Living” and “human” may appear redundant, but they are necessary modifiers. For some suppose a robot with sufficient artificial intelligence could be a teacher—à la The Jetsons—while others believe the images or voices of humans neither present nor necessarily alive could do the job.) The behavioral psychologist B.F. Skinner plays a starring role in this account, though Watters is careful to make him a part of the story rather than the whole story, as sometimes happens.

That story, I assumed before opening the book, would begin in the 1970s and end with the pandemic: an origin framed by our present travails. Instead, the book starts far earlier and concludes exactly when I thought it would start. Why? Why write about teaching machines few of us have ever heard of and none of us have ever used?

Watters’s answer is simple: contingency. The concept is central to her work, here and elsewhere. Nothing is inevitable; agents and actors, however large or small, whether moral, amoral, or immoral, are responsible for what happens in our world. Which is to say, someone (singular or plural) is responsible, and therefore may be held accountable, for what happens. The rule is at once epistemic and political. And the rule has a practical correlate: resistance to, and persistent debunking of, the mythology of Silicon Valley.

That mythology unspools a neat narrative in which an irresistible destination—the present status quo, defined as it is by the latest digital innovation—draws the past toward itself in a simple linear movement. Smartphones, blockchain, cryptocurrency, web3, whatever gadget or invention defines the era functions like a final cause in the philosophy of Aristotle. Knowing the end, the mythmakers tell the just-so story of enlightenment, development, business, and genius—think of all those contested origin stories featuring famous dropouts with names like Gates and Jobs and Wozniak—that led inexorably to our present, a present we now understand to be necessary. Such a narrative is bulletproof by design. It can’t be called into question in hindsight, since it was fated to occur in any case. Which means it is as futile to criticize new technology today as it was then. The arc of history bends toward Cupertino.

This way of telling the story is not so much teleology as predestination. What technology wants technology gets; like Calvin’s God, its will is as powerful as it is inscrutable. Watters isn’t buying it. Her writing reads like a curmudgeonly skeptic growing up in a fundamentalist town. She won’t believe just because you tell her she has to. She knows she doesn’t. There is more than one way to poke holes in the official story. Her method of choice is cultural history. Teaching Machines is the result.

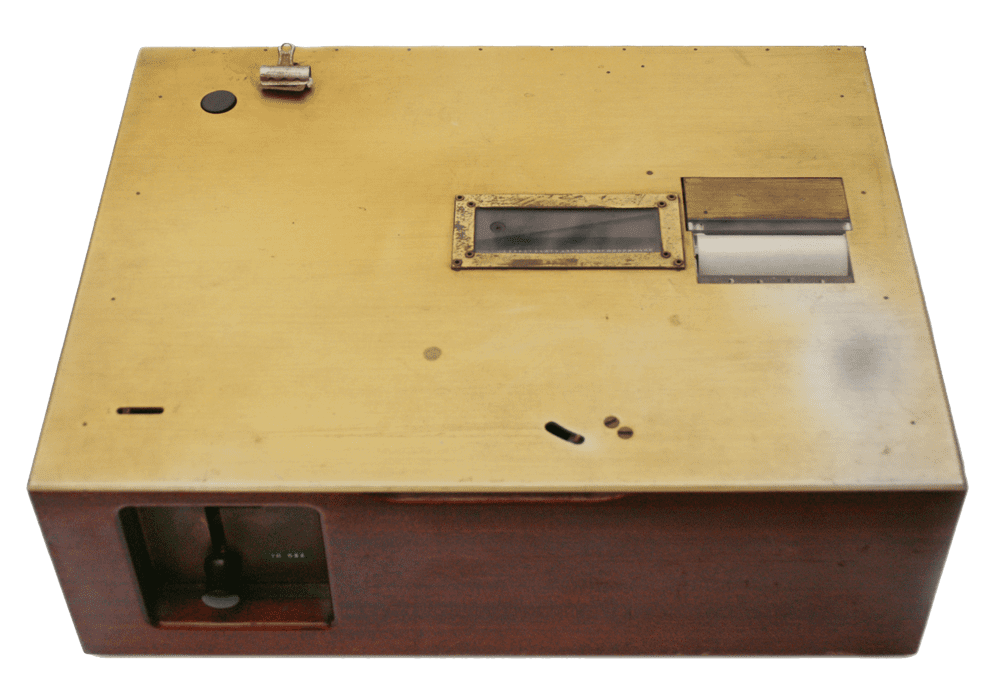

The initial idea for a personalized teaching machine, in which a student at a desk would answer questions via programmed instruction on a device of her own and at her own pace, came a full century ago, in the 1920s. Some combination of corporate skittishness, lack of a market, design failures, and the Great Depression doomed any chance it might have had of widespread adoption. B.F. Skinner was already well-known for his theories in behavioural psychology—you may know him from the infamous “Skinner Box” or perhaps from his proposal to train pigeons to aid in the use of guided missiles during World War II—when he began to develop the concept of individualized teaching machines in the 1950s and ’60s. His name became attached to the idea of such machines and contributed to his fame, but his two decades’ worth of work on them came to naught. Indeed the whole drama, which includes top-bill casting as well as cameos by the likes of Sidney Pressey, Thomas J. Watson, IBM, Sputnik, James Bryant Conant, Paul Goodman, and Noam Chomsky, is a rather dreary affair. A few obsessive entrepreneurs keep pounding their heads against the wall, but they never quite crash through.

At times this compulsive monotony lends the book a repetitive air; Watters’s attention to the granular (and she has done her work in the archives) requires that we be nearly as frustrated as the Ed Tech inventors, only at them rather than with them. But that’s probably unavoidable. Watters wants to disrupt the disruptors, and one of their tricks, when they aren’t denying the value of history altogether, is to reduce narrative complexity into digestible bits—worthy of a TED Talk or a YouTube video. The antidote, therefore, is detail, and Watters’s book is full of it.

But not for its own sake. As she writes, “To understand the teaching machines of the mid-twentieth century is to understand the teaching machines of today.” To portray them as a failure, which in one way they were, is to misunderstand them. For “they were not a flash-in-the-pan, as some scholars have suggested, but a harbinger.” Toward the end of the book she draws a straight line from Skinner’s notion of “behavioral engineering” and “contingencies of reinforcement” through Jacques Ellul’s critique of “technique” to the “behavioral design” of our digital architecture and the “nudges” of Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein’s “choice architecture.” All this has happened before, and all this will happen again.

The dream, in other words, of a perfectly automated education never died. It only assumed novel forms. Zoom isn’t the dawn of something new. It’s the latest iteration of a very old idea.

The dream, in other words, of a perfectly automated education never died. It only assumed novel forms. Zoom isn’t the dawn of something new. It’s the latest iteration of a very old idea.

Can teachers be replaced? That is the fundamental question animating a century’s worth of theories, inventions, and efforts to test the hypothesis in controlled experiments. Though fundamental, the question is, in a manner of speaking, an empirical one. Set up one class with tablets, a pre-set curriculum, and freedom to move through the material as students please, then test their results against those of a parallel, typical classroom. But that raises a second question, which overlaps with and informs the first—namely, whether teaching and learning are the sort of thing that can be measured the way we measure GDP, cholesterol levels, or the efficacy of vaccines. Is the principal “product” of education the testable knowledge of facts, figures, dates, names, and times tables? Is it, in the terminology of James C. Scott, legible to the master plans of engineers and designers? Or is it something else?

As a teacher myself, I am disinclined in the extreme to believe that teachers are rendered redundant by machines of any kind. But even if some technologies perform well enough under certain conditions for certain persons (I am thinking of language software like Duolingo), it is the nature of education as a philosophical question that must determine our response to the ideology that sanctions teaching machines and the feeling that their triumph is irresistible. If education is not reducible to discrete content that can be regurgitated and thereby assessed—and it is not—then teaching machines are no more inevitable than robotic substitutes for parents. Mothers and fathers are not a bearable though highly inefficient means of incubating, birthing, feeding, clothing, and housing children. The same, making the relevant changes, goes for teachers.

But we should be honest with ourselves. Some among us do conceive of society as a machine, of families as mere components of that machine, and thus of maximal efficiency or productivity—sometimes euphemized as “a good economy”—to be the summum bonum of our common life. For such a view it may well be a problem when parents choose to forsake “productive” careers to spend time with their children. For such a view it is far from implausible that the aim of education might be achieved by means of artificial intelligence. For the aim of this style of education is to be seamlessly plugged into the machine, in this case the very machine whose pedagogy has from the beginning supervised and tutored the young people in question.

We must not, then, assume a shared view of the nature of education. We must articulate one and advocate it—or at least heed the prophets who do. In Christian circles the buzzword here is “formation,” and though sometimes the term can be used in vacuous or clichéd ways, it’s the right one. Education names the comprehensive formation of young people in the goods and ends of human life, with especial interest in the goods and ends of knowledge, broadly construed. That is why, among other reasons, the body, the soul, and the heart have always been united with the mind to form the single though complex object of classical pedagogy. A wicked genius is a failure, not a success, for this style of education. To learn what is worth knowing means, in part, learning what is worth loving. That is why, in turn, education has always been intertwined with worship. Without a final end to unite the proximate ends of knowledge, the disciplines fragment and we are left with little more than the industrial technocracy of Max Weber’s instrumental reason. Which, we are right to lament, is largely what we have today.

I imagine Watters would dissent from this account, at least in part. Perhaps she would cut the piety, add an activist slant, and construe the whole more strongly in terms of individual freedom. But I take her to agree in principle that education is more than banking (to use Paulo Freire’s language) and teachers more than mechanisms of information-deposit. Education concerns the person, and persons—to borrow now from James K.A. Smith—are not brains on sticks. Nor, to stick closer to Watters’s own imagery, are persons ill-designed machines with software in need of an update.

This goes to the heart of her vision in the book. When “students are taught … to think like computers,” she writes, then

teaching and learning become the purview of the machine. . . . Thus, the phrase “teaching machines” takes on new meaning: this is the work of computer scientists who “teach” machines, those who specialize in “machine learning.” And as machines are purported to “think” and to learn, our minds now too are imagined as machines, and our educational endeavors are conceived as systems to engineer.

What is most striking from the social history Watters unfolds is the simultaneous obsession with individualized, personalized learning, on one hand, and with automated mass learning, on the other. Like the lords of Ed Tech today, the advocates of teaching machines argued that rows of silent children, each staring at an identical personal device while following preprogrammed instruction sequences, was both an alternative to mass education on the one-size-fits-all model and a pedagogical approach adapted to each individual in her own unique particularity. To put it plainly, the cognitive dissonance involved beggars belief. The truth is that no education reform has ever been so impersonal or mechanical—in almost a literal sense—as this one. If ever there was a philosophy of teaching and learning modelled on the factory, this is it.

No education reform has ever been so impersonal or mechanical—in almost a literal sense—as this one. If ever there was a philosophy of teaching and learning modelled on the factory, this is it.

On the page, Skinner and his comrades sound like nothing so much as ad men hawking the latest cheap gadget for the suburban family. Instead of a toaster or an ice maker easing the drudgery of the 1950s housewife, it is the teaching machine that will ease the drudgery of the public school teacher. In both cases, it is men setting themselves the task of “fixing” “women’s work.” The implicit assumption being that such work may be performed as well or better by a machine. In any case, it only makes it worse, not better, that they seem to have actually believed their own sales pitch.

And not only them. Apparently something else that has not changed since Skinner’s time is the credulity of journalists. It is as though newspapers and magazines simply let the advertising firms write their stories for them. Long before anyone saw, much less used, either Skinner’s or others’ teaching machines, headlines were cheerily proclaiming the end of teachers, the birth of a new day, and a revolution in education. It took outsiders (among them radical critics like Goodman and Chomsky) to see through the charade.

There are at least two lessons for us here. One is that new technology bears the burden of proof. The onus is on Zuckerberg and Bezos and Dorsey, not us, to demonstrate, over time and with transparency, that their widgets will not worsen our common life. The alternative—serving collectively as their perpetual test subjects while they run social and psychological experiments on the populace, solely to further their bottom lines—is intolerable. It makes us fools. We can be and do better than that.

The second lesson is that prudent responses to novel technologies hold the potential to draw together strange bedfellows. At times Watters, an avowed progressive, sounds conservative, even reactionary. That’s not because resistance to Ed Tech is inconsistent with the left. It’s because right and left aren’t useful coordinates for relating to technology. Some kind of Burkean phlegm is demanded by the dizzying inventions, political upheavals, and sheer amassed power of our digital overlords. Perhaps this is one of those very few areas in which right and left can link arms in solidarity, standing athwart the Big Five yelling, Stop!

At the very least, something very much like that is necessary if we are going to reclaim some degree of moral and political agency in the face of these giants. Doubtless such work demands not only prudence but patience, across multiple generations. In fact, if we want the next generation to take up this work, the classroom—the real one, not Zoom—is the perfect place to start. While we’re at it, maybe we could hire some more teachers. Preferably the human kind.