I

In the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle argues that the highest and best form of friendship is the sharing of thoughts and speeches between two noble people who are equal and alike in virtue. Such friendships, he continues, flourish best in a well-ordered polis. The polis relies on virtuous citizens for its strength and good character, and the citizens in turn rely on the polis to cultivate and sustain virtues like friendship, courage, justice, prudence, and temperance.

As the age of democratic revolutions dawned, leaders began to worry that this virtuous cycle would break down. Republican government would produce material abundance, which would lead to luxury, which would lead to the corruption of the very virtues that made such prosperity—and other goods—possible. Those concerns certainly haven’t gone away. If anything, anxieties about social and moral decay are at a fever pitch. This seems to be a perfect time to take a closer look at how precisely it is that strong friendships and healthy communities co-create each other.

Much of the writing about themes like virtue, friendship, citizenship, character, and their reciprocal connections tends to remain at a high level of abstraction. I’d like to do something different, zooming in on a microcosmic institution to describe the concrete, conjoint, intricate operations of friendship, character formation, and institutional health within the place I know best: Christ College, the honours college of Valparaiso University.

James Davison Hunter once defined a comprehensive moral community as “an environment where intellectual and moral virtues are not only naturally interwoven in a distinctive moral ethos but embedded in the very structure of the community.” In other words, such a community doesn’t just preach about virtues, it embodies them in daily concrete action.

Founded in 1967, Christ College remains one of the oldest free-standing honours colleges in the country. Its three hundred students are concurrently enrolled in another of Valparaiso’s colleges—Arts and Sciences, Business Administration, Engineering, and Nursing and Health Professions. In this way, all of Christ College’s classes are populated by students with a broad variety of knowledge, skills, interests, and ambitions. The honours curriculum spans four years, but it’s the first-year program that is critical for setting all of the terms, expectations, practices, principles, and ideals that will inform the rest of the curriculum, and define the common life of the community.

The signature feature of this first year, the practice that creates life-long friendships, is the Christ College Freshman Production. Part of this looks like a normal Great Books seminar. Between eighty and ninety entering students take an eight-semester-credit-hour course each of the first two semesters that consists largely of reading the great works of the human imagination in literature, philosophy, history, and religion, all grouped around the central question, What is the good life?

But the other part of the curriculum goes beyond the seminar room. During their first semester on campus, the entire class is required to write, produce, and perform five times for the entire campus their own original musical production, based on one of the themes the readings have introduced. This is the Freshman Production.

Over the half century that students have been putting together this production, it has served as a learning laboratory and a character incubator. Every year, ninety adolescent strangers learn to discover one another’s gifts, to celebrate the diversity of such gifts, to rely on one another, and to discern quickly that the excellence of the final performance depends on such diversity. One freak year almost all of the musicians in the class were trombonists, which led to both special challenges and special opportunities for the composers. This process of collective discovery teaches the value of diversity far more effectively than a few lectures could. Moreover, during the semester students are graded on a pass/fail basis. Cooperation is the essence of healthy moral communities, and competition is often inimical to them.

Learning to keep your head and your temper in the midst of this kind of clamorous self-examination, to be at once charitable and critical, civil and contentious, is an essential part of liberal education and a preparation for public discourse in the larger society.

This kind of education through theatre means there’s sometimes going to be conflict and disagreement among the students, along with a great deal of hard work and no small amount of disappointment. The student writing committee may come up with three or four splendid ideas, but they must adopt only one. Many students, therefore, must not only give up their preferred choice but also work industriously for several weeks to advance what was once someone else’s rival idea. This process of intense argument governs the writing of the script itself, the composition of the music, the set design, the choreography—all the things that make the show. But at some point, after hours of negotiation and a good deal of anger and frustration, all (well, almost all) students become deeply invested in the overall quality of the production. They move, however painstakingly, from conflict to common purpose, back to conflict, and eventually to the final performance of the production itself. These continuous rhythms between conflict and common purpose are essential to a well-functioning republic and vitally important in these days and times.

The original creators of the Christ College Freshman Production had at least hoped for this much. But they had not anticipated the way in which the experience of making a play together would make students better readers and writers, thereby extending the range of friendships from well beyond the immediate community to the democracy of the dead. The kind of liberal education that Christ College provides involves the effort to entertain seriously those ideas and images that seem initially strange, sometimes altogether obscure, and often threatening. And this process in turn involves approaching texts written long ago and far away with an attitude at once humble and suspicious.

We now notice that our students look at literature with new eyes, once they themselves have had to work to invent characters who are consistent, once they themselves have had to learn how to connect endings to beginnings, to carry forward thematic emphases through an entire ninety-minute performance. They become much more respectfully intrigued by questions that invite them to discover the theme, the structure, the argument, and the overall intention governing a text written by Plato or Jane Austen. In brief, their own experience of making something, their own sense of the difficulty in giving both form and substance to an idea or a feeling, makes them at once more respectful and more critical of the works of literature, philosophy, history, and religion they are reading concurrently with their work on the production.

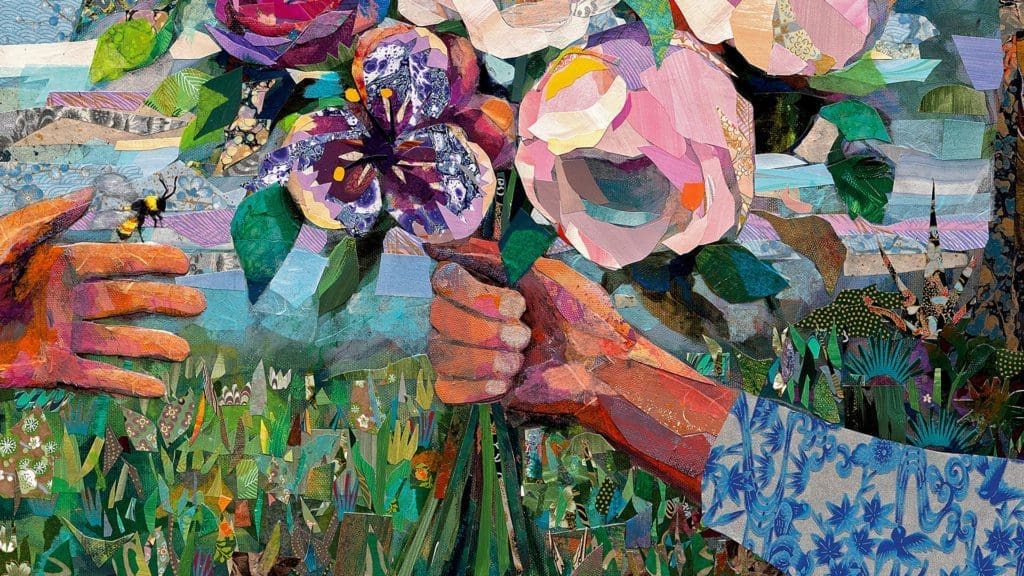

Few things are more noble than disciplined, spirited, and pleasurable activities in service to the public good that engage the imagination as well as the intellect, the body as well as the soul, and the affections as well as the reason.

The great literary critic Wayne Booth, in his book The Company We Keep: Notes on an Ethics of Fiction, sought to extend Aristotle’s notion of friendship to include a reader’s relationship to the implied author of a text. Though he recognized that books will never fully be friends, he nevertheless made a persuasive case for his more general claim that we are formed by the company we keep and by the character and quality of the relationships we form within that company. By inviting his own readers to consider implied authors as friends, he encouraged people to read in a spirit of humility and charity. “Read as you would have other read you; listen as you would have others listen to you,” he writes. The freshman performance unleashes startling creative energies. It forges immediate friendships between students and between students and texts, even the ancient ones.

Over the years students have structured their musicals around a variety of themes: friendship in an era of Facebook, Zoom, and texting; the deterioration of the family; the prospect of eco-catastrophe; the culture wars; the increasing threat of random violence; the problem of exclusion and community; urban decay, terrorism, and the dilemma of religious pluralism. Thus, for most of the month of November, the mood of the college is transformed by the energy and imagination of the entering students. Our rather pedestrian refectory, a modest, all-purpose room, becomes a brave new world, complete with elaborate backdrops, sound systems, lights, multi-tiered stages, murals, and an improvised orchestra pit. Students linger for hours in the Christ College commons with copies of Machiavelli’s The Prince (a typical week’s reading) in one hand and copies of the script for the production in the other. Some are obviously in costume and others may or may not be.

The honours college has about two hundred sophomores, juniors, and seniors, almost all of whom were in their own Freshman Production; indeed, all of them must appear on stage in addition to their other roles in producing the show. After the premier performance of any Freshman Production, comparisons and contrasts are in the air, some of them invidious, others trivial, many of them sophomoric (literally and figuratively). Students investigate the intricate relationship between a community and its art (from ancient Athens to the present), between the several creators and the single final product, between the larger culture and a given, very localized, highly perishable but intensely felt element of it. Students pursue these questions with an intensity that is a vital part of a liberal education, with an energy that fuses them into a community of colleagues and friends.

The communal response to the Freshman Production is so extensive and heartfelt that the college eventually institutionalized some of it. On the Thursday evening after the Freshman Production there’s a panel of faculty members, and another of sophomores (the most severe critics), to respond to the show. A panel of first-year students then responds to the responses. For better or for worse, and in sometimes raucous exchanges, the community gets to know itself better, to see what the deepest concerns and impulses that move its members look like, feel like, and sound like. Then at Christmas Symposium each class puts on a series of skits. The sophomores invariably offer up a parody of the Freshman Production for that year, thereby providing a theatrical commentary on it. Learning to keep your head and your temper in the midst of this kind of clamorous self-examination, to be at once charitable and critical, civil and contentious, is an essential part of liberal education and a preparation for public discourse in the larger society.

The late Richard Hofstadter wrote extensively about two frequently opposed dimensions of the life of the mind: piety and playfulness. Students tend to lose themselves in the collective venture of making theatre, thereby sometimes achieving a balance between the spirit of playfulness and the demand for serious coherence and integrity. The exercise trains the affections and then educates the imaginations.

The Freshman Production enables students to learn to do many worthy things, but how do they learn to do them well? The teaching faculty model much of what they expect. The course is team-taught, and the students witness in the first week principled public argument among their teachers as one by one they rise to raise questions about and sometimes criticize the weekly plenary lecture delivered by one of their colleagues. The students’ wonder at this behaviour astounds the faculty every year. Most students are surprised to learn that faculty disagree among themselves, that they can do so publicly while still remaining friends, and that thought itself is birthed in public debate among peers before it can become private.

Aristotle’s concept of friendship was wonderfully elastic, embracing friendships of expediency or utility (two strangers painting dormitory rooms together one summer), friendships of pleasure (two people who simply for a time amuse, delight, or otherwise entertain one another in a pleasurable way), and friendships of virtue (two people who value each other for who they are, wish the other’s well-being as much as their own, and bring out the best in each other). Friendships of the highest and best type offer utility, pleasure, and good character of course. But as we have seen, though friendships may be primary in some sense, they are not self-sufficient and they do not remain healthy without a broader institutional context that gives them support, encouragement, and sustenance. The interlacings of virtue, character, friendship, and community must remain to some degree mysterious. Nevertheless, the Christ College experience has shown again and again that few things are more noble than disciplined, spirited, and pleasurable activities in service to the public good that engage the imagination as well as the intellect, the body as well as the soul, and the affections as well as the reason.

Nevertheless, as Christ College students well know, friends are more often than not simply given to one another. They come as gifts rather than as the result of human exertion, even though the love between friends, philia, is grounded finally in choice. There seems to be widespread agreement among the several traditions that have shaped the ethos and the logos of Christ College about the premier virtue of friendship. Aristotle thought of it as the crown of the virtues. And though the One who gave Christ College its name showed his love for his own disciples primarily by laying down his life for them, thus revealing the essence of agape, he also at last elevated the master-disciple relationship among them that they had enjoyed for almost three years when, on the evening of one of the last days of his life, he told them simply, “I now call you my friends. Love one another as I have loved you.”