T

Today, the Church’s greatest competitor is not secular humanism, but a spirituality that has transcended the space that the modern Church provided for spiritual development.

Near Extinction

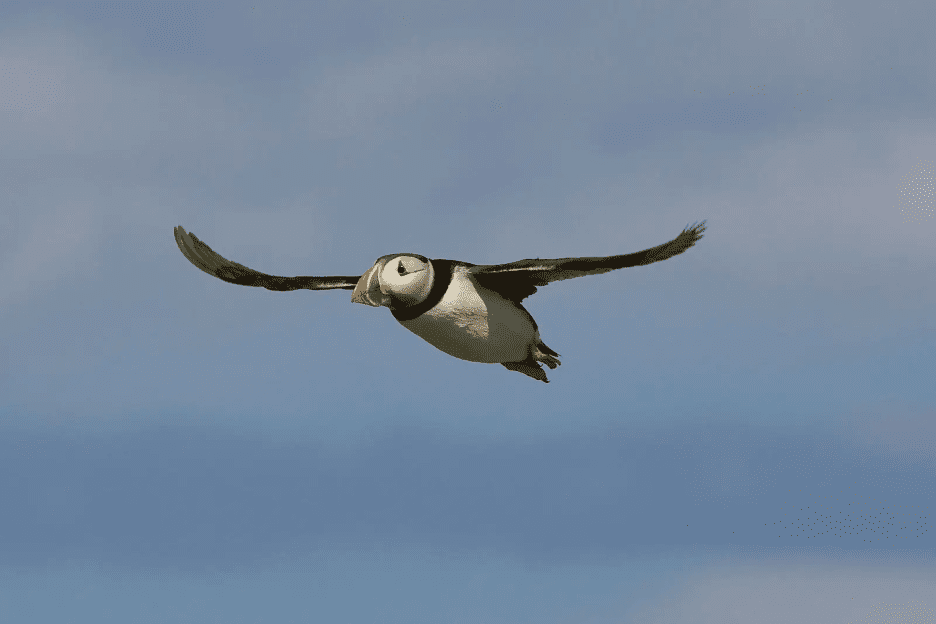

The puffins on Eastern Egg Rock off the coast of Maine’s Muscongus Bay had always been there. The salt-licked granite boulders that make up this treeless outcrop breach the ocean’s surface like a petrified wave, providing perfect nesting grounds. The island’s seven scraggy acres, unreachable by most land predators like racoons or minks, always summoned the puffins home. Their orange feet and beaks plunged into the neighbouring sea like defiant sparks. Emerging with bills full of herring, the triumphant white-chested auks settled on their shielded enclave in constellations of feathered stars.

Along with black-capped terns and eiders, the puffins had always been on Eastern Egg Rock, until they weren’t. Hunting and the sins of millinery—the profitable fashion for puffin feathers that enhanced women’s hats in the nineteenth century—ended their gentle reign. The last known puffin nest on Eastern Egg Rock was recorded in 1885. Puffins as a species survived, of course, but they moved to Newfoundland or even farther north. What replaced them were common seagulls. Less dependent on sensitive conditions for survival, seagulls, after all, could even eat trash. So it was that people a generation ago commonly accepted that there just were no puffins in Maine.

Eastern Egg Rock. Photo by Lisapaulinet.

The Christian mystics had also always been there, until it seemed as if they weren’t. The Quietist controversy of the late seventeenth century put mysticism under suspicion in Catholic circles, and the loss of monasteries in Protestantism drastically (though not completely) reduced their ranks. By the early twentieth century, the most visible features of Protestantism and Catholicism had largely hardened into fortresses of conflicting doctrine. Even the Orthodox world, embattled by centuries of Ottoman dominance, neglected its own great mystical tradition, as evidenced by the eclipse of the icon. The piercing gaze of gold-nimbed saints were too frequently replaced by timid copies of Renaissance art.

Addressing the Problem

In the 1960s, a young Stephen Kress was a graduate student in zoology, stationed in Maine at Hog Island in Muscongus Bay. While browsing a copy of Maine Birds by Ralph Palmer, he read that puffins had once bred nearby on Eastern Egg Rock. A budding ornithologist, Kress knew that puffins were philopatric—that is, they always returned to their homes to nest. Accordingly, the only way to restore puffins to Eastern Egg Rock would be for some to be hatched there. Shortly after completing his PhD, Kress hatched his own plan to restore the old Maine breeding pattern, plans that were ridiculed by Ralph Palmer himself, alongside other luminaries of the birding community. Such resistance only hardened Kress’s resolve. Owing to his persistence, eventually the Canadian government agreed to provide six puffins from Newfoundland to be stationed on Eastern Egg Rock. Five survived, and the Canadians agreed to provide more—nearly two thousand more over the next sixteen years. Still, the puffins did not choose Eastern Egg Rock as a return site. Kress and his team did what they could to dislodge the gulls, even shooting them, to no avail.

What Kress would eventually be for puffindom, Evelyn Underhill (1875–1941) would be for Christian mystics. Thomas Merton, Charles Williams, and T.S. Eliot all indicated their debt to her. The latter identified in Underhill a unique “consciousness of the grievous need of the contemplative element in the modern world.” A London socialite educated at King’s College, Underhill enjoyed a privilege that most modern occultists would snap their wands to attain: she was a member of the Order of the Golden Dawn. There she regularly experienced spiritualist rituals set apart from the Christian liturgy, presumed to be too staid and familiar. She was friends with the co-inventor of the modern Tarot card deck, the esteemed occultist Arthur Edward Waite. Underhill even wrote a defence of magic against its detractors. Slowly, however, she came to see that magic was “tainted by a certain intellectual arrogance. A divorce has been effected between knowledge and love.”

Underhill enjoyed a privilege that most modern occultists would snap their wands to attain: she was a member of the Order of the Golden Dawn.

At the turn of the twentieth century, books on mysticism were slowly emerging. The Anglican Dean Inge’s Bampton Lectures were published under the title Christian Mysticism in 1899, and the Roman Catholic Baron von Hügel’s The Mystical Elements of Religion appeared 1908. But owing to her ability to speak to ordinary people, Underhill eclipsed both of them with the book that made her famous, Mysticism, published in 1911. In it, however, there is a lingering bias against institutions. There is little discussion of Christ, sin, the cross, or grace. The puffins, in other words, were still suspicious of what was once their native land.

Recovery

To lure the puffins back to Eastern Egg Rock, Kress aimed to “think like a puffin.” He set up audio recordings of bird calls, to some effect. But it was the decoys that were most successful. Real puffins congregated around the decoys for hours at a time, acclimating them to their ancestral home. The seagulls, however, were still a problem. Kress’s strategy on this front was to attract another population to compete with them. Using the same strategy—bird calls and decoys—Kress and his team lured the terns back as well, who fended off the gulls and made conditions more hospitable for puffins. In 1980 terns nested on their former home for the first time since 1936. Still, there were no puffins. But on July 4, 1981, all of Kress’s efforts were rewarded. The sight of a puffin with a fish in its beak could mean only one thing: it was on Eastern Egg Rock to feed its recently hatched pufflings.

Decoy and puffin. Photo by Robert F. Bukaty.

If puffins are to mystics what Eastern Egg Rock is to the church, then Underhill’s vocation was similar to that of Kress. She learned that the “mysticism” on offer in London spiritualist circles was merely a decoy. She coined a word for such shallow spirituality fit for seagulls: “mysticality.” Her friend Arthur Waite insisted to the end that his approach to mysticism was superior to Christianity. “There is no God but God, and the soul is his prophet,” he thunders in his autobiography, Shadows of Life and Thought. “We are That which we seek.” But Underhill was unconvinced by his claim, in passages such as that one, to surpass Christianity, Islam, and Hinduism in one cocksure swoop. Perhaps she had come to see that the Order of the Golden Dawn, and its spinoffs such as Waite’s Brotherhood of the Rosy Cross, were as rent with schism as was the Christian church. “Plotinus can never have had to face his own beastliness,” she confessed, as her deepening mysticism put her face to face with her own patterns of sin.

As she warmed toward classical Christianity, Baron von Hügel himself became her spiritual director. “Somehow, by his prayers or something,” she wrote, “he compelled me to experience Christ.” Under Hügel’s guidance, she moved from what she called “white-hot Neoplatonism” into a more Christ-centred form of faith. She nearly became Roman Catholic but—with Hügel’s blessing—discerned a call to the Anglican tradition instead. She followed up Mysticism with her book Practical Mysticism in 1914. “This [mystical] life shall not be abstract and dreamy, made up, as some imagine, of negations,” Underhill there insists. “It shall be violently practical and affirmative; giving scope for a limitless activity of will, heart, and mind working within the rhythms of the Divine Idea.” The book was published just as the Great War commenced. Here was a rugged spirituality, one that could survive global conflict intact.

She nearly became Roman Catholic but—with Hügel’s blessing—discerned a call to the Anglican tradition instead.

Maintenance

Today the puffins are thriving on Eastern Egg Rock again. Like the wolf comeback in Minnesota or the revival of bald eagles in Illinois, the return of Maine puffins is one of the true ecological triumphs of our time. Kress and his trainees still monitor the tiny island, fighting back the seagulls or rogue landed predators, regulating how many tourist boats are permitted to visit. But the profusion of those striped orange beaks on Muscongus Bay, stuffed with fish to feed their young, is evidence of Kress’s undeniable success.

Evelyn Underhill, the first woman chosen to be an outside lecturer at Oxford, slowly concluded that mysticism flourished best within, not outside, classical Christianity. She insisted on calling a more mature publication not Mysticism but Mystics of the Church. “There is always, in the church as in the family,” Underhill intones in the book, “a perpetual opportunity of humility, self-effacement, genteel acceptance; of exerting that love which must be joined to power and sound mind if the full life of the Spirit is to be lived.” Though she appreciated Meister Eckhart’s vertiginous rhetoric, she came to prefer the clarity and dependability of Jan van Ruusbroek instead. Without disdaining the disestablishmentarianism of the Quaker George Fox, she could say his “Inner Light would have burned with a better and truer flame had it submitted to the limitations of the lamp.”

Evelyn Underhill, the first woman chosen to be an outside lecturer at Oxford, slowly concluded that mysticism flourished best within, not outside, classical Christianity.

Following Hügel’s death, under the guidance of an Anglican spiritual director named Somerset Ward, Underhill grew in gentleness toward herself and others, and she flourished as a spiritual director and retreat leader. She supplemented her former counsel of pure detachment by advising the right kinds of attachment—bonds of fidelity to people and institutions that Christians do well to make. She emphasized not exalted feelings or metaphysical theatrics but the work of the will in establishing the Christian life. She grew in her love of Eastern Orthodoxy, finding in the Fellowship of St. Alban and St. Sergius—which brought Anglicans and Orthodox together—a more enduring thrill than the Order of the Golden Dawn. “Whoever is that little woman?” the Orthodox theological giant Sergius Bulgakov once asked about her in one such meeting. “She knows way too much.”

Underhill’s last book, which finally earned some grudging respect from her many critics, was simply titled Worship, giving due attention to all the main branches of Christianity. In it, she insists that the institution “checks religious egotism, breaks down devotional barriers, obliges the spiritual highbrow to join in the worship of the simple and ignorant.” Still, there was never anything churchy or romantic about her chosen attachment to recognizable, routine Christianity. She once compared the church to an essential service like the Post Office, where “irritating and inadequate officials behind the counter” will always tempt exasperation. Even so, she insisted to one of her directees, “the adoration to which you are vowed is not an affair of red hassocks and authorized hymn books; but a burning and consuming fire.”

The institution “checks religious egotism, breaks down devotional barriers, obliges the spiritual highbrow to join in the worship of the simple and ignorant.”

Mystics and Mysticality

Thanks to Kress, the news has been good for Maine puffins, but it is mixed for spirituality in the Anglophone world today. Even while those who once professed their atheism are drawn to the church’s mystics, and despite high-profile conversions, post-Christian prophets of what Underhill would call “mysticality” flourish as well. They insist that true spirituality is inevitably heretical, and they bristle with excitement when relating stories about mystics who rankle church authorities, which they consider a sign of success. The liturgical rhythms of Christianity, these self-styled mystics tell us, are unnecessary; but subscribing to their newsletter or pricey retreat is necessary indeed. Like the hunters of a century ago, they plunder the church’s mystics for potential insights, robbing them of their plumage. But the church, like Eastern Egg Rock for puffins, is the mystic’s truest home. A century and a half since her birth, Evelyn Underhill still calls us back to our ancient nesting ground.

Author’s note: Thanks to the detailed reporting of Philip Conkling for the full story on Kress. Those interested in learning more about Evelyn Underhill can read Dana Greene’s luminous biography, to which this article is indebted, or attend the forthcoming conference at Nashotah House organized by Greg Peters, “The Monastic Ideal of Evelyn Underhill.”