O

Of the many, many peculiarities of our age, one of the most peculiar is the widespread embrace of a dissident identity. In red states and blue cities, Midwestern factories and East Coast faculty clubs, in the bro labs of Silicon Valley and barber shops of Southern towns, in unemployment lines and in gilded offices, we gather, we complain, and we fantasize about how we might rise up and resist the man.

On its face, the existence of widespread dissidence is something of an oddity, if not an impossibility. After all, at its root, dissidence—from the Latin, dissidentia—means “contrary to” or “set apart from.” That numerically vast and ideologically divergent portions of our society all see themselves as members of a minority resistance movement is not only logically impossible and historically implausible but also psychologically bizarre. And yet here we are. Absurdity notwithstanding, we are a vast community held together by little more, it seems, than our shared commitment to dissent.

From one perspective, a commitment to dissent is a necessary aspect of any society that aspires to health. As the prophetic traditions remind us, dissidence is an essential guardian against the drunken tyranny of a collective mind; a critical—if unwelcome—portal exposing us to the light of truth. From Isaiah to Augustine, Teresa of Ávila to John Brown, Dorothy Day to Václav Havel, dissidents stand apart from the conventional and summon us to the sacred.

From another perspective, though, our peculiar brand of ubiquitous dissidence is unsettling, corrosive to sharing life with others. It suggests not only broadly discordant visions of culture (a mainstay of Western culture wars) but also divergent accounts of cultural power: who holds it, the uses to which it should be deployed, and our personal and tribal relationships to it. It indicates, to use the pointed parlance of the moment, utterly contradictory accounts of oppressor and oppressed, and it suggests not simply that we are contending for different visions of the world but that we believe we are inhabiting different worlds altogether. In this respect, constant self-identification with dissidence does not suggest the health of our society, but its terminal sickness.

A Troubling Self-Assessment

Even so, I am a dissident. And I am also a Christian. Because of this, I would like to think that at my best moments—even at my average moments—this fact has more than a little bearing on the shape of my life in the world. And sometimes it does.

However, as I have observed the emergence of our culture of dissidence, a culture in whose thrilling currents I, too, have been swept away, I have had the growing—and somewhat embarrassing—sense that my dissident identity may not yet be deeply Christian. I confess I have wondered whether, despite its restless and self-assured energy, my dissidence might at times be masking a deeper conformity. That I, rather than standing meaningfully apart from our great civilizational bar fight, might actually be simply one more participant in it; one more sweaty fool who, though boasting of moral purpose, is actually just throwing wild punches in the dark.

When I stop and assess the various expressions of my dissident energy, I see a few unflattering realities. I see intellectual self-deceit: a belief that knowing some things somehow means knowing all things. I see moral equivocation: a willingness to mistake anger for insight and contempt for courage. I see tribal loyalty: an instinctive rush to excuse my friends and expose my enemies. I see rank dehumanization: a dark desire to discard the dignity of those with whom I disagree. And I see self-preservation: a defensive and wary concern for my own interests above those of my enemies.

Of course, this is not the whole portrait. Alongside these civic vices, I also see deep curiosity, informed conviction, a certain fearlessness before power, strong conciliatory instincts, and a willingness to suffer. Still, what I see more often than I would wish is not the open heart of Christian dissent, but the insular fury of cultural contest. And I suspect that I am not alone in the struggle to pick aright in the distinction.

A Table for Three

One night, while in the midst of this exploration, a friend asked me whether I could summarize what I was beginning to understand about the peculiar character of Christian dissidence. I said, somewhat off-handedly, that I was still thinking it through, but that at its best, I believed Christian dissidence has three aspects to it: the contemplative, the critical, and the convivial. Noting his blank stare, I opted for a culinary image: “Okay, let’s try this: Julian of Norwich, James Baldwin, and Robert Farrar Capon walk into a bar.” After a moment’s pause, he said, “Okay. That makes more sense. Make sure to use that.” So let’s use it.

Julian of Norwich: The contemplative. Julian of Norwich (ca. 1343–1416) may seem an unlikely place to turn for an education on Christian dissidence, but her life and work nonetheless bear witness to a distinctive form of holy resistance.

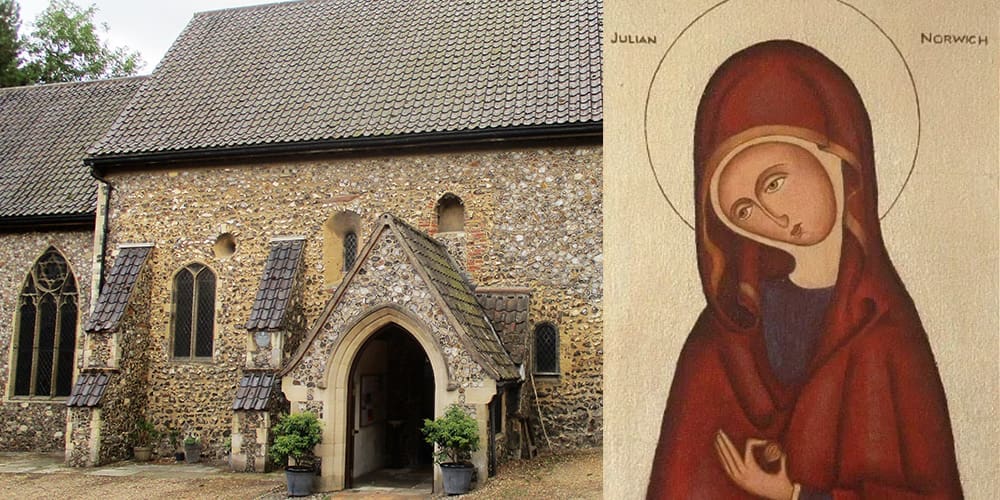

St Julian’s Church, Norwich, UK. Photo by A. Mitchell; Julian of Norwich, ca. 1343—ca. 1416. Artist unknown.

Hers are the oldest surviving writings in English by a woman. Her writings portray God in atypically maternal terms, describing the soul’s relationship to God as that of child to mother. As she puts it, “The mother may give her child suck of her milk, but our precious Mother Jesus can feed us with Himself. . . . The mother may lay the child tenderly to her breast, but our tender Mother Jesus can homely lead us into His blessed breast by His sweet open side.” Each of these facts suggests a woman committed to living against both the gendered and the theological conventions of her time.

How does one move from “I truly believed that I was at the point of death” to “All will be well”? The answer, for Julian, was a transformative contemplative encounter with a loving God present among the deathworks of the world.

But perhaps the most revolutionary aspect of Julian’s life and work is the hope she held in the face of the obliterating shadow of death. Julian’s life was, as many medieval lives were, stalked by mortality. When she was a child, the Black Death, a bubonic plague that killed between twenty–five and fifty million people in Europe and as many as two hundred million worldwide, repeatedly ravaged her city. When she was a young woman, religious war—that most constant of European plagues—transformed the city of Norwich into a killing field. And though it is difficult to know a great deal about her personal life, most prominent Julian scholars suspect that she was a widowed mother who may have also lost her children. Given these things, and given the widespread veneration of suffering that marked a great deal of the medieval church, it is no surprise that Julian’s work, Revelations of Divine Love, begins in the context of death:

When I was thirty and a half years old, God sent me a bodily sickness in which I lay for three nights and on the fourth night I received all the rites of the Holy Church and did not believe that I would live until morning. After this I lingered on for two days and two nights. And on the third night I often thought that I was dying, and so did those who were with me . . . [yet] I endured all day, and by then my body was dead to all sensation from the waist down. . . . [The Parson] came and brought a cross, and by the time he came my eyes were fixed and I could not speak. The parson set the cross before my face. . . . After this my sight began to fail and the room was dim all around me, as dark as if it had been night. . . . The upper part of my body was beginning to die. My hands fell down on either side, and my head settled down sideways for weakness. The greatest pain that I felt was shortness of breath and failing of life. Then I truly believed that I was at the point of death. . . . I said, Benedicite Dominus! Everything here is on fire!

Over the course of the past several years, and certainly the past several months, it has become harrowingly common—and not without reason—for those speaking of the disintegrating state of Western culture to speak of it in terms of death. The death of character. The death of communities. The death of institutions. The death of the rule of law. The death of democracy. And, of course, the death of human beings. In a moment of profound cultural dissolution, the constancy of death seems apparent to us all. In response to this cultural death, many of us—and I am often among them—have found ourselves in an almost constant state of fear. Fear of the past. Fear of the future. Fear of the other. Fear of the disorienting contingency of our lives and the life of the world itself. And, as it often does, this fear leads us to grope for all manner of control, for some semblance of agency over all this death. If we could only control the narrative, control the resources, and control our enemies, then (we tell ourselves) all would be well. This, then, is the cycle we see: death gives rise to fear, fear gives rise to control, and control—as it must—finally gives way to death. And the cycle continues.

And yet it is here, precisely at the fear before the “point of death,” the moment when “everything here is on fire,” that Julian can teach us a different way. For while her work begins in the wilderness of death, it does not end there. To the contrary, it mysteriously blooms out into a joyful landscape of hope: “All will be well,” she tells us. “All will be well and all manner of things will be well.” How does one move from “I truly believed that I was at the point of death” to “All will be well”? The answer, for Julian, was a transformative contemplative encounter with a loving God present among the deathworks of the world. Indeed, as her revelations unfold, the story she tells transforms from a story of the abandonments of death to the story of a God who is present in reality, who shares in her suffering, and who transforms her death through redeeming love. Listen again to her words:

At the same time that I saw this bodily sight, our Lord showed me a spiritual vision of his familiar love. I saw that for us he is everything that is food and comforting and helpful. He is our clothing, wrapping and enveloping us for love, embracing and guiding us in all things, hanging about in tender love, so that he can never leave us. . . . And this our good Lord answered all the questions and doubts I could put forward, saying most comfortingly as follows: “I will make all things well, I shall make all things well, I may make all things well and I can make all things well; and you shall see for yourself that all things shall be well. . . . Know well that what you saw today was no delirium. Accept it, believe it, and hold to it. You shall not be overcome.”

In these words we find the contemplative essence of Julian’s dissidence. In the face of certain death, she looks within this death and there finds the loving, suffering, ultimately transformative presence of God. For Julian, this presence gives rise to the hope not only that we ourselves but that all of humanity, and all of history, is held in the maternal heart of this presence, confounding forever the illusory nightmares of final despair.

Julian’s hope is a powerful corrective for a contemporary dissidence too often fuelled by an epidemic of fear. And it is a call to a more sacred dissidence that begins in and remains animated by hope born of the ongoing contemplation of the loving presence of a God who, in spite of the real terrors before our eyes, assures us that all will be well.

James Baldwin: The critical. Unlike Julian, James Baldwin more naturally fits the profile of a dissident. Born in New York City in 1924, Baldwin died in France in 1987 in self-imposed exile from the nation he both loved and lamented, a dissident to the end. As a gay black man living in the middle decades of the twentieth century, Baldwin’s very existence was, in its own way, an unintended form of resistance. This fact gave him a keen sense of the perilous boundary between freedom and danger. He carried a prey’s vigilant attunement to the realities of power: its location, its expectations, and its judgments.

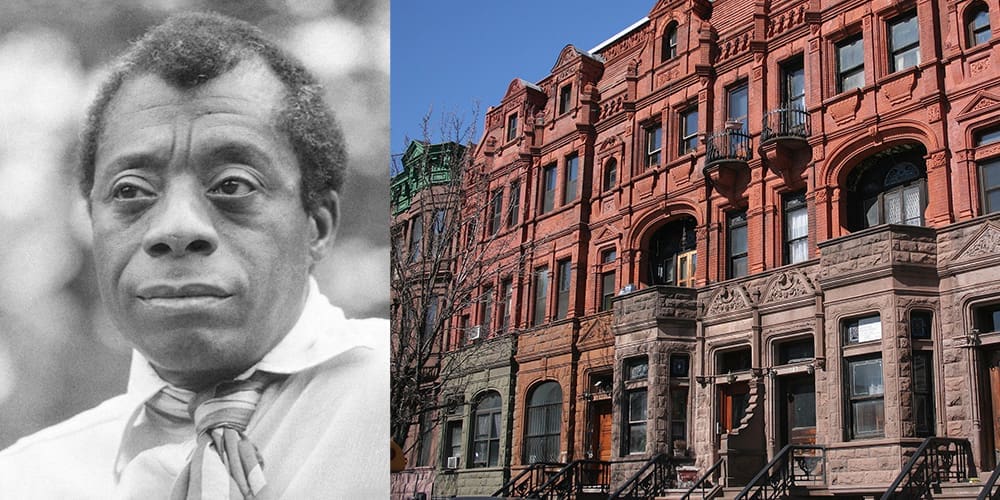

James Baldwin, 1924—1987. Photographer unknown; Harlem, NY. Image by Ilan Costica.

Over the course of his life, Baldwin came to see that abuses of power were expressions not first of violence but of deceit; that it was deceit—what he called “the lie”—that gave power its, well, power. For Baldwin, the clearest and most sweeping example of this fusion of power and deceit was Western culture’s hypocritical sheltering of white supremacy. How could one explain the fact that a culture that understood itself as a global beacon of freedom could be the same culture that perpetually and violently enforced racial inequality? Baldwin’s answer was seemingly straightforward: Western culture’s self-conception was a tragic form of vain self-deceit. Baldwin wrote pointedly, “All the Western nations are caught in a lie, the lie of their pretended humanism. [These myths are] both dishonestly self–congratulatory and ultimately self–destructive.” However, Baldwin applied his account of deceit not only to the ideological foundations of Western culture but to the intimate chambers of the human heart. For him, the danger of mythic entrapment was a danger against which every human being needs to defend. As he put it, “The truth is a two–edged sword—and if one is not willing to be pierced by that sword, even to the extreme of dying on it, then all of one’s intellectual activity is . . . a wicked and dangerous fraud. . . . Anyone who insists on remaining in a state of innocence long after that innocence is dead turns himself into a monster.” For Baldwin, then, the malignancy at the heart of all abuses of power—both personal and civilizational—is our willingness to shelter lies.

Because Baldwin believed that self-deceit lies at the heart of both personal and civilizational abuses of power, his dissidence took the form of a relentless commitment to telling the truth.

If these observations were true in his own time, they are, incredibly, even more so in our own. At the time of this writing, our communities are awash in a sea of willful and brazen lies. Lies about history. Lies about current events. Lies about ourselves. Lies about our political allies. Lies about our cultural enemies. Lies from government spokespeople. Lies in our press. Lies on our social media feeds. Lies in our own mouths. And, as Baldwin warned us, the purpose of these lies is always to provide legitimacy for the abuse of power. So the abuse is among us. Behind the thin veil of deceit, we are witnessing a truly extraordinary re-narration of history, corruption of institutions, theft of resources, violations of rights, and punishment of dissent. These are mendacity’s halcyon days.

Because Baldwin believed that self-deceit lies at the heart of both personal and civilizational abuses of power, his dissidence took the form of a relentless commitment to telling the truth. The truth about the history of American culture. The truth about the hypocritical selectivity of our ideals. The truth about the psychological effects of this hypocrisy on all who fall under its shadow. The truth that the only way to heal our minds, our souls, and our communities is through a painful but ultimately liberating embrace of the truth itself. Indeed, this was the incandescent heart of Baldwin’s artistic dissidence: the furious devotion to exposing the lie and replacing it with the truth. As he puts it, “The role of the artist is exactly the same as the role of the lover. If I love you, I have to make you conscious of the things you don’t see.” And elsewhere, “I love America more than any other country in the world, and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.”

Baldwin’s twofold commitment to exposing the lie and to speaking the truth is an important reminder of the fundamentally critical dimension of the dissident’s calling. Like Baldwin, we too are called to examine, to expose, and to eschew the hypocritical and self-serving lies at the heart of Western culture. Indeed, this is the very essence of dissent. And like Baldwin, we are to labour with equal diligence to replace these lies with the truth—the truth of who we have been, who we are now, and who we may yet be. For it is here, in these truths, that we find the only possible basis for our personal and collective healing.

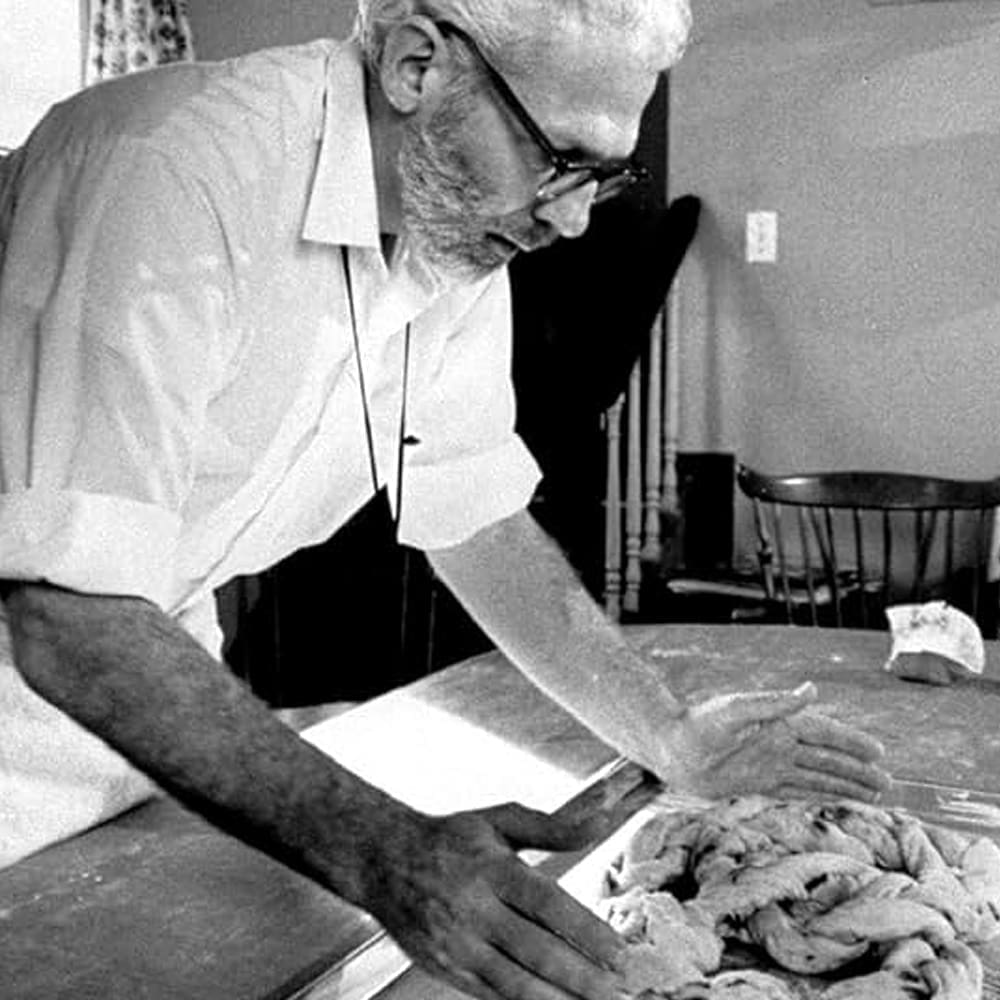

Robert Farrar Capon: The convivial. If Julian of Norwich seems an unorthodox choice for a meditation on Christian dissidence, then our third table guest, Robert Farrar Capon (1925–2013), may seem even more so. In truth, as I considered the role of the convivial in dissent, more than one name came to mind: M.F.K. Fisher, Jim Harrison, Julia Child, and Anthony Bourdain all would serve us well in this respect. But in the end, I returned to Capon, who, even in this extraordinary group, always seems to say it best.

Robert Farrar Capon was an American Episcopal priest, writer, and amateur chef who spent virtually his entire career in New York City. And though he never wrote anything that could be described as overtly or partisanly political in nature, his work nonetheless has the consistent inescapable character of dissent. In Capon’s case, the object of his dissent was the impoverished sensual imagination of much of American culture, and certainly of the American church. Specifically, he believed that both were captive to a technocratic ethos that instrumentalized the world and spiritualized vision that denigrated it. For Capon, however, the world—the gratuitously teeming, verdant, and fructifying world—was neither a resource to be exploited nor a prison to be escaped but a gift to be received with delight and lifted up with joy. His was a sensuous vision, at once holy and irreverent, that called both church and world away from lives of presumptive control and circumspect pieties, and into lives of full participation in a celebratory feast of the world’s ordinary and yet overwhelming abundance.

Though this theme of sensuality characterizes all his work, its most powerful and raucous expression may be found in his masterpiece, The Supper of the Lamb. It is an extraordinary work—a work of theology in the form of a cookbook, a cookbook in the form of an ecstasy—whose pages flash with the desire of a lover, the skill of a chef, the praise of a theologian, and the giddy wonder of a child. And it is here that we find his most powerful words of dissidence against the manifold diminishments of the world. For the sheer pleasure of it, I quote at length:

It was God who invented dirt, onions and turnip greens; . . . God who, at the end of each day of creation, pronounced a resounding “Good” over his own concoctions. And it is God’s unrelenting love of all the stuff of this world that keeps it in being at every moment. So if we are fascinated, even intoxicated by nature, it is no surprise: we are made in the image of the Ultimate Materialist. . . . If this book has any claim to make, therefore, it is that food is precisely an epiphany of the greatness of our nature. . . . It is a sacrament, a real presence of the gorgeous mystery of our being. . . . We are not simply the users of creation; we are, all of us, called to be its offerers. The world will be lifted, as it was always meant to be, by our priestly love. We can, you see, take it with us. It will be precisely because we loved this Old Jerusalem of a world enough to bear it in our bones that its textures will ascend when we rise; it will be because our eyes have relished the earth that the colors of its countries will compel our hearts forever. The bread and pastry, the cheeses, the wines, and the songs go into the Supper of the Lamb because we do: It is our love that brings the City home.

In these words we find the essence of convivial dissidence, a fleshly insurgency against both the disenchantment and the misenchantment of the glories of the world.

In our age, too, the world has fallen on hard times. In many religious imaginations of both the East and the West, the world remains opposed to the soul, the flesh to the spirit, the fields of the earth to the watered gardens of heaven. In a great deal of religion, the old diminishments of the world remain. But in ways that Capon could scarcely have imagined in 1967 when he published The Supper of the Lamb, our culture’s instrumental account of the world has devolved into a drunken orgy of extraction that threatens its very viability. With the burning of our forests, the mining of our hills, the poisoning of our fields and rivers, and the endless, grasping accumulation of the world’s bloated classes, we are well beyond the world’s diminishment. We are gazing on the smoking omens of its destruction.

For Capon, however, the world—the gratuitously teeming, verdant, and fructifying world—was neither a resource to be exploited nor a prison to be escaped, but a gift to be received with delight and lifted up with joy.

The facts of the world’s demise are not new, of course. Nor are they in any way hidden from view. They are, rather, ignored. Indeed they are scorned. For we aspire to pillage. We crave to consume. We build generational wealth through the sale of weapons designed to reduce the human body to mist. We plan golf courses on the bulldozed graves of shattered children. And then, while gazing over the acidic tides of dying seas, we raise our glasses to the fabulous—if broadly inaccessible—wealth bestowed on us by our piratic genius.

Detail from “Still Life with Onions” by Paul Cézanne, 1896–98.

Robert Farrar Capon, 1925—2013. Detail from cover of “Supper of the Lamb”.

What, in the face of such monstrous dissolution, does dissidence require of us? That we, with Capon, insist once again on the irreducible convivial character of the world and of the celebratory responsibility of our lives within it. Ironically, besieged as we are by endlessly disgruntled avarice, Capon’s call to the awakening and ordering of desire may be one of the most important aspects of Christian dissidence. In the face of apathy, we attend. In the face of greed, we bestow. In the face of militarized joylessness, we, to evoke Capon, gather songs at our tables and “fling our joy at the stars.” In sum, given our clutching state of affairs, one of the most truly dissident acts in this world may be simply to open our doors to our neighbours, set food on our tables, look one another in our shining faces, raise our glasses, and pray the joyful prayers of creatures at home in the world. In the event that you find yourself struggling for the words for such a prayer, one of Capon’s prayers should work just fine:

O Lord, refresh our sensibilities. Give us this day our daily taste. Restore to us soups that spoons will not sink in, and sauces which are never the same twice. Raise up among us stews with more gravy than we have bread to blot it with, and casseroles that put starch and substance in our limp modernity. Take away our fear of fat, and make us glad of the oil which ran upon Aaron’s beard. Give us pasta with a hundred fillings, and rice in a thousand variations. Above all, give us grace to live as true men—to fast till we come to a refreshed sense of what we have and then to dine gratefully on all that comes to hand. Drive far from us, O Most Bountiful, all creatures of air and darkness; cast out the demons that possess us; deliver us from the fear of calories and the bondage of nutrition; and set us free once more in our own land, where we shall serve thee as thou hast blessed us—with the dew of heaven, the fatness of the earth, and plenty of corn and wine. Amen.

Tables of Dissent

This, then, is what I take to be the essential character of a truly Christian dissidence in our time: the willed convening of the contemplative, the critical, and the convivial; or, if you prefer, of Julian, Baldwin, and Capon. In one respect, what makes this strange convening so powerful is their shared commitment to love. To love of the God who dwells with us in pain. To love of neighbour—both the oppressor and the oppressed—and the truth that sets each free. To love this world for its infinite array of ordinary astonishments. Christian dissidence is, as all Christian things are, elementally bound to love.

But in another respect, what makes this particular combination so powerful is its essential interdependence. Each of these—the contemplative, the critical, and the convivial—is its own powerful dimension of dissidence. But each needs the other in order to become fully itself. The contemplative without the critical and the convivial devolves into the therapeutic. The critical without the contemplative or the convivial collapses into accusatory joylessness. And the convivial without the contemplative or the critical lounges into hedonistic indifference. But together, they offer a powerfully complex grammar of dissidence: hope in the face of death, truth in the face of lies, and gratitude in the face of greed. The call of Christian dissidence is to embrace each of these. For only in so doing we may yet find—in a final nod to Capon—this broken Jerusalem of a world transformed into a city of love.