C

Christian humanism is a phrase that, unlike most “isms,” tends to elicit more curiosity than baggage. But just what is it, exactly, and how can it help us? To help us answer this question, Comment commissioned New York Times columnist David Brooks to interview theologian Luke Bretherton. So much of Comment’s approach to the big questions of our day is animated by this tradition, one that we believe goes all the way back to the incarnation and finds its first expression in the hours before Christ was crucified. As you read the following conversation, we hope you’ll begin to see a historical canopy shimmer into focus, and with it, a frame for new alliances and pathways forward. There is a cause to be championed in the fourth version of the story that Luke tells here, and Comment, little by little, is seeking to develop it through our own pages and in the networks we are weaving through Breaking Ground. Our goal is to resource a Christian humanist presence in the public square that is clear on the fundamental questions facing human life and flourishing in this time of profound change and political contest. We seek to do so in a way that proves to be superior to and more compelling than either integralist or post-liberal arguments on the one side and anti-Christian, anti-humanistic visions on the other—all while not falling prey to the bland platitudes of procedural liberalism.

—The editors

David Brooks: I have had this instinct for the last several years that we’re in the middle of some epic confrontation between the forces of humanization and the forces of dehumanization. Among the forces of dehumanization I would include current forms of politics, technology, and capitalism. The forces of dehumanization seem to be rising and on the march. Meanwhile the forces of humanization—the study of literature and the arts, community service, loving forms of faith—these things seem to be beleaguered and in retreat.

Those of us who want to be on the side of humanization are left with the urgent question, What is humanism? So I’ve been buying books about humanism, and half of them are just about atheism. The word “humanism” seems to have become a stand-in for secularism. So when I first heard you use the phrase “Christian humanism,” I was intrigued.

Let’s start with the most basic question: What is Christian humanism?

Luke Bretherton: All humanist traditions start with the questions: What does it mean to be human? And how do we value the dignity and worth of each human? The answers to those questions have implications for not only how we understand and value the human but also how we evaluate different kinds of political, economic, and social projects. Does this or that way of doing things bring out what is fully human, or does it not?

There are many varieties of humanism that can emerge out of different religious and philosophical traditions. Obvious ones would be ancient Greek and Roman philosophies, particularly Stoicism. But we can also look to a figure like Maimonides in the Jewish tradition or traditions of Islamic humanism exemplified in the work of Ibn Sina and Ibn Rushd.

Christian humanists begin with the theological claim that Jesus is fully human as well as fully divine. A scriptural frame for this, one that has been hugely influential in the last two thousand years of artistic production and literature, is the scene in John 19 when Pilate presents Jesus to the crowd and says, Ecce homo: “Here is the human.”

Pilate is preaching against himself, saying, “Here is the true human.” If you really want to know what it means to be human, if you really want to know what it means to live a truly human life, look to Jesus Christ. It is Jesus’s life, death, and resurrection that give us the picture of true humanity to which we can then respond.

So the idea is that even though we’ve lost much of our humanity through sin and idolatry, we can recover it through contemplating Christ. That process of mimesis, of copying, is a way of becoming like Christ, and so becoming truly human again. One way of taking on the likeness of Christ is through looking at his picture, whether that’s Rembrandt or an icon or some other image, or by reading a story that depicts a Christlike way of life. Another is through participating in Christlike activities.

Christian humanism, then, is this sense that our humanity is revealed in Jesus Christ. A revelation that invites us into various ways of recovering our humanity through either contemplating portrayals of Christ or active participation in Christ’s way of being in the world, such as through loving service of others.

DB: This is fascinating. So every moral philosophy is based on an image of what human beings are like. Given what you’ve just been describing as Christian humanism, Machiavelli is popping into mind as a contrast. Machiavelli says, “Well, what are humans like? They’re basically selfish, shallow, they seek popularity. So to rule these creatures, it’s better to be feared than loved.” Machiavelli starts with a picture of what human beings are—which is pretty low—and then from there he builds a realist model of politics.

The Christian humanism you’ve described feels completely different. And it frankly doesn’t strike me as an accurate description of what most people are like most days. It’s an aspirational ideal. It’s like an image of what humans ought to be.

LB: Let me go back to Jacques Maritain, who was a Catholic philosopher and advocate of Christian democracy, and someone who was key to recovering Christian humanism in the 1920s and ’30s over and against deeply anti-humanistic ideologies associated with communism and fascism. Maritain made a distinction between what he calls anthropocentric humanism and Christian humanism. Anthropocentric humanism makes (using old language) man the measure of man. That’s what we see in Machiavelli.

The problem, as Maritain identifies it, is that what is human then becomes totally self-referential. We become turned in on ourselves. There’s a loss of any transcendent horizon. There’s a loss of what it means to be human as having inherently transcendent goals. So, for example, politics is reduced to being only about pursuing material benefits and security. It ceases to have any meaning or purpose beyond that. Human flourishing is simply a question of securing either economic well-being or, as it was for Machiavelli, the glory and status of the political community.

That early modern move to reduce the human to a wholly immanent horizon of reference, focused on the self-interested pursuit of material goals, characterizes libertarianism, and various non-religious forms of anarchism, socialism, and liberalism, as well as many other modern philosophies. These are anthropocentric forms of humanism that have made humans the sole measure of everything. The question is, If there is no transcendent goal to which the human being is accountable, does everything become possible? Are there moral limits to what we can do to each other in the name of creating the true human?

On Machiavelli’s account, the answer is that anything is possible. If it’s all about power and the pursuit of political glory for its own sake, then you can treat other humans as units of social administration or as commodifiable products, as in slavery. You can pursue violent projects of social engineering to secure power for yourself and those like you. We have seen this played out time and again in modern history.

A humanism that is cut off from a transcendent reference point, without a non-material telos or end, is inherently self-contradictory and destructive. You start with efforts to create a Soviet Man and you end up with the gulags. You start with the efforts to create a German Fatherland and you end up with the Holocaust.

DB: Now that we have some inkling of what Christian humanism starts with—the person of Jesus as the full human—I want to ask you, What does it do for us? I’ll ask it this way: In the Jewish tradition, there are images of the human. And some of them are pretty special humans: Moses, Isaac, Jacob, Rebekah, Naomi. But they’re definitely flawed. The act of admiring and even trying to copy them is not the act of moving beyond the human. Christian humanism seems pretty different, as it’s trying to imitate an actual perfect person, no?

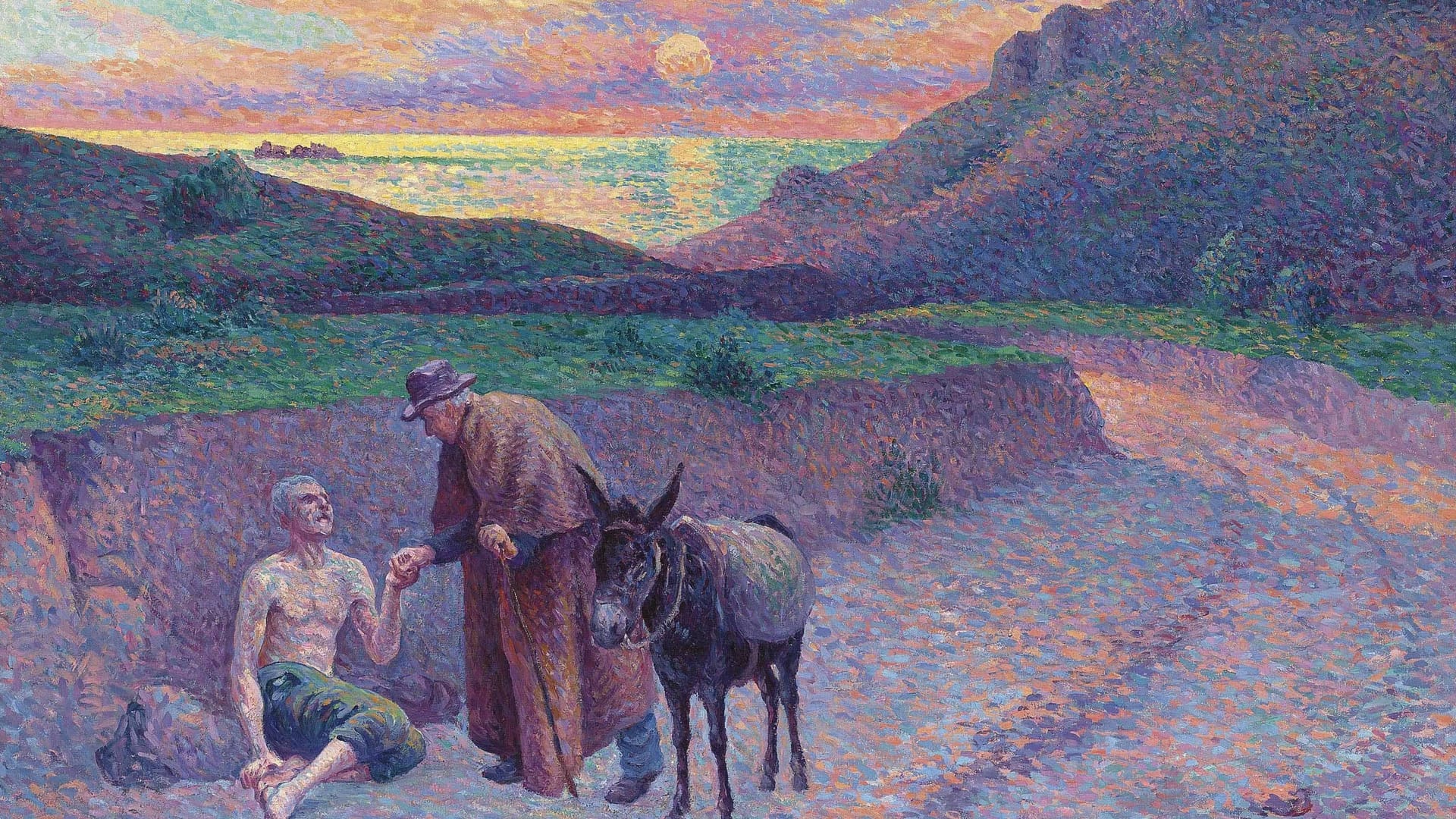

LB: The point about the figure of Christ is that we become more able to inhabit and be present to frail flesh. In Christ’s humanity, we discover our own. It’s not the contemplation of a Zeus, some immortal body that does not suffer. It’s always—and this goes back to John’s Gospel and the presentation of Christ by Pilate just prior to crucifixion—it’s always the contemplation of the broken body of Christ. The one who stands before Pilate and the crowd is someone who is beaten, bound, and about to be executed. We contemplate and copy one who is subject to betrayal, false accusation, imprisonment, and state, judicial killing.

You don’t discover your humanity through transcending pain, tragic loss, or ambiguous, conflicted, difficult relations. It’s not gnosticism. It’s not a movement out and beyond the material conditions and realities of our lives. It’s always a movement into the suffering, trauma, oppressive conditions, and deeply wounded nature of what it means to be human east of Eden.

We see this exemplified in something like the parable of the good Samaritan. As hearers of the parable, we discover the Samaritan’s (and our) humanity at the point of his encounter with the stranger. But who is the stranger that the Samaritan encounters? He’s someone who’s without aid, without friends to help him. He’s suffering. And given relations between Jews and Samaritans, he’s an enemy. The Samaritan is depicted in the story as the truly human one. His humanity is revealed at the point of encounter and how he responds. His response is simultaneously a gesture of enemy love, help to one suffering, and friendship. It contrasts with those who think, “Don’t touch, stay away, protect yourself,” and so pass on by and thereby deny not only the humanity of the one robbed and beaten but also their own humanity.

We only discover our own humanity through the encounter with another not like us. And it’s at this same point of encounter that we discover that Jesus is suddenly present to us. That’s the big takeaway in Matthew 25. “When did I help you, Christ?” It’s when you welcomed the stranger, clothed the naked, fed the hungry, visited the prisoners. So the real presence is not just in bread and wine; the real presence of Jesus is also found at the point at which we discover our humanity through responding to suffering, broken, frail flesh in Christlike ways.

That’s the profound gift of Christian humanism. It puts front and centre a movement into the place of suffering, oppression, and weakness, not a movement above and beyond it. Because that is the place where Jesus shows up. That is the place you really get to discover both who Jesus is and what human flourishing is. And that’s what you see in patristic writers like Gregory of Nyssa, who, in his fourth homily on Ecclesiastes, calls for slaves to be seen as fully human in the light of who Christ is and to treat slaves as equals. It’s a classic early Christian humanist text, precisely because he’s seeing that it is only when you mix with the slave, when you take seriously the life of the lowly, that you discover both your humanity and encounter Christ. You discover your humanity because that’s where you really discover where Jesus is. Because he’s always found with the outcast, with the oppressed, with the suffering and weak.

LB: Absolutely. There’s a lovely line from one of the earliest theologians––Irenaeus of Lyons––where he says, “The glory of God is a human being fully alive.” The fully human is the mother tending the child. It’s wiping the bottom of the elderly dementia patient too sick to do it for themselves. That’s actually the full measure of the human. But also, as with Jesus’s presence at the wedding at Cana, this vision of what it means to be fully human includes times of feasting and joy. And as in his parables, it also includes contemplation of and delight in creation and the natural world: vines, sheep, and mustard seed can teach us what it means to love God and neighbour and thereby discover what it means to flourish as a human. These mark creaturely life in communion with others and creation. They are all forms of the blessed life. The shalom-like life.

That richness is the picture of the fullness of being human. And that’s what truly glorifies God. Unfortunately, a strong strand of Christianity has had a more anti-material—we might say gnostic—element, which is focused on self-abnegation, the emptying of myself. It says less of me equals more of God. I am but a worm.

But the point Christian humanism affirms is not that I am nothing. It is that I am frail, and I am weak. To truly understand what it means to be human is to recognize our fragility and to live according to that. Medieval and Renaissance paintings often included a skull or some other memento mori to remind us of our finitude and frailty. Or as the Ash Wednesday liturgies put it, you are dust and to dust you shall return. We are not gods. All attempts to live as gods are characterized by hubris that lead to the destruction of myself or others. To say I’m the maker of my own world, or I’ve just got to be strong enough to secure myself in the world, is to render myself less than human. It is to become inhuman.

You can never secure yourself. You’re dependent on God. You’re dependent on others. You were born a mewling babe, and you will be a gibbering old person. And that’s a central part of what it means to be human.

DB: It’s at once humble, but also a very high image of human nature.

LB: Yes, because that person, the old person who’s forgotten everything, is still fully human. And that’s the key emphasis in Christian humanism: That the incarcerated are fully human; they are no less human than the free. That the poorest person with no education has full dignity and should be given as full an ability to participate in determining their living and working conditions as the Harvard graduate living in a penthouse. Christian humanism declares that whatever your condition, mental, economic, cultural, whatever it is, you are fully human, and your humanity participates in Christ. It is secured in Christ, who died for you, and in whom your life is liberated and redeemed.

That’s the metaphysical claim that anchors the whole thing. That can generate a Mother Teresa. Or Salvation Army officers doing what they can for the least, the lost, and the last, because everyone is someone for whom Christ died. And their humanity is realized in Christ. And we also, when we encounter and respond to those suffering or oppressed, discover our own humanity at its fullest.

DB: It leads to some very practical consequences, doesn’t it? As you were speaking, I was reminded of story from some years back, about the comedian Aziz Ansari. He met a young lady, took her home, and, at least according to the accounts published in the media, more or less forced himself upon her as she grew more and more distressed. He wasn’t aware of what was going on in her head or how she was feeling. And she felt wretched. And so it became a scandal for Ansari. I remember thinking when I read about it, all he had to do was say to himself, “Well, here’s a soul made in the image of God right in front of me in this room.” And if you say that, you’re probably going to end up treating the person the way they should be treated. But it’s so easy to cover that over and dehumanize the person standing in front of you.

Can you please draw out the way in which what you’re describing is just a daily practical way of seeing other human beings, and seeing yourself?

LB: Again the good Samaritan parable exemplifies this. That story tells us that a person doesn’t have to be like me for me to see their full humanity. I don’t have to agree with them. They don’t have to be beautiful for me to treat them right. They don’t have to have authority or power for me to respect them. They don’t have to have achieved or done anything special to be considered worthy. I see in that other person—who I might find ugly or threatening or difficult or smelly—I see in them someone made in the image of God and in whom Christ is present. And at that moment, I can care for them with reverence.

This goes back to what I was saying about anthropocentric humanism. If I’m only going to treat others with full dignity who are on my ideological wavelength, then I’m not going to treat those I consider enemies with dignity. And that’s part of the polarization we see today, when so many are only prepared to treat others with respect and recognize them as one deserving of care if they follow a narrow ideological checklist. If they don’t, then they are treated in inhuman ways. Even if, as seems to be happening more and more today, they’re your own family.

Whereas, if I’ve got some sense of who you are that lies beyond our ideological differences, who you are as more than what is immanent or useful, then you are not reducible to a bundle of ideological commitments. There’s more to you than that. I think that has profound salience for us today.

DB: Let’s talk about the intellectual history of Christian humanism and then the different branches, the different ways it’s shown up in the world. When do people become self-consciously Christian humanist?

LB: That’s a very good question. I would say this emphasis on how Christ reveals our humanity in a way that lies beyond our political, economic, or cultural differences and on discovering one’s humanity through caring for the least, the lost, and the last is right there from the very beginning. You see it in New Testament stories like the good Samaritan or in the letter to the Colossians. It’s then picked up and developed in the earliest theologians. Then there are the medieval strands, whether expressed through religious orders like the Benedictines or Franciscans, the poetry of Dante, or the practical mysticism of Catherine of Siena. You then have the humanism of the Renaissance articulated by the likes of Erasmus, or more powerfully still by the indigenous Incan theologian Guaman Poma.

But we probably don’t really get the term “Christian humanism” until the modern period. It’s here that you suddenly have this full-court press of anti-human ideologies coming into view, ideologies that are gaining the power of the modern state and the market to wholly destroy the shape and form of the human and to annihilate whole parts of humanity. And so suddenly there’s this alarm raised: “Oh, hell, how do we defend the human?” On top of that, people start seeing Christians seduced by these anti-human forces. They’re seeing the church sell its inheritance for a mess of pottage, all in the name of securing itself through deeply anti-human social engineering projects like nationalism. And so Christian humanism is revisited as a tradition that needs to be revived within the church itself.

DB: I’ve heard you talk about the four stories in which Christian humanism gets expressed. Or four ways that Christianity has shown up in the world, including to this day. Could you run through those?

LB: Well, the one I begin with is a negative story. You might call it the “West to the Rest” story. In this story, Christianity emerges primarily in Western Europe. This story ignores the church in the East, and the church in North Africa, Ethiopia, and Persia. The emergence of Christianity is told in largely Eurocentric terms.

And it’s a story about how, under the sacred canopy of Christianity, we have the emergence of science, the Enlightenment, and a rational, properly ordered way of existing. It’s a story of how we move beyond our superstitions and create the glories of Western European civilization: Shakespeare, the novel, the formation of universities, and so on. These all emerged in Western Europe as the flowering of what it really means to be human. And the story says that Christianity was the crucible that enabled all of this to emerge.

On this first version of a West to the Rest story, European man is the measure of what it means to be human.

Europe exports this vision through colonialism, forcing it on others, making it a universal measure. At the same time, the European way of life is seen to be threatened. It’s threatened from within, by anti-Christian and anti-European ideologies (communism being a primary example), and also by forms of relativism. So there’s a need to defend Christianity, not in the name of defending the proclamation of Jesus Christ as Lord and Savior, but in the name of defending Europeanness as the height of humanity over and against what is seen as decadent or anti-Christian elements within. And then there’s a felt need to defend this “Christianity” from that which would overcome it from without—that could be Islam, communism, China, or whatever it is.

You see this exemplified in something like Action Française, which was a movement that emerged in the late nineteenth century and really flowered in the early twentieth, and then fed into the support of the Vichy regime in France in the Second World War, which obviously collaborated with the Nazis and was itself fascist. The leaders of Action Française were not Christian, but they viewed Christianity as a vital cultural anchor to securing the glory of France as a civilization. They claimed to defend family, faith, and flag against the secularizing, liberal, communist, and other forces that were seen to threaten the “greatness” of France. In short, they wanted to make France great again.

Thousands and thousands of Catholics bought into this. Jacques Maritain initially bought into this, thinking, “We need to defend family and faith and flag.” But what they missed was, it was really a defence of some imagined Frenchness, rather than of Christianity. Christianity was the cultural prop to a highly exclusionary and oppressive civilizational project.

DB: Sounds like American Christian nationalism today.

LB: I think that’s exactly what Trump offers. Steve Bannon is an interesting contemporary example of this dynamic. I would say he echoes Oswald Spengler. Spengler was a German historian and philosopher in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. He had something of a tragic view of Europe and a cyclical view of history. He argued that we were entering a time of great cataclysm, and needed a dictator figure to rise up and defend European civilization over and against that which threatened it from within and threatened it from without. And he co-opted Christianity into this defensive project in order to secure the basis of civilization expressed in family, faith, and flag. In its contemporary articulations, this is white supremacy: The measure of the true human, to which Christianity is aligned, is the white European man. And anything that threatens the supremacy of that needs to be defended against and defeated by any means necessary.

Now there’s a variation on that story, which we’ve touched on already, which is another West to the Rest narrative. But this second story views Christianity as a passing stage on the path to anthropocentric humanism. Which again, can be exported elsewhere through colonialism of one kind or another. You see that in figures like John Stuart Mill or Jeremy Bentham. It’s a non-religious liberal view, often quite technocratic in its frame of reference.

Unlike the first story, this narrative views Christianity as a problem rather than a necessary phase or anchor. Now that we’re enlightened, we don’t need religion anymore. Through science and technology, we can re-engineer the world and make it fully rational and properly ordered. We don’t need transcendent goals. We just need to focus on human-centred political, economic, and social projects, using our now enlightened rationality. And that’s pretty much the view taught in most modern universities today. Religion is viewed as a superstition that should have no place in public life.

But this view is no less imperialistic. It’s no less Eurocentric. And it should be said that in this version of the story there is very little if any place for the fragility and frailty of what it means to be human. Or for the centrality of mutual care and bearing each other’s burdens. We are required to be autonomous, independent, fully rational agents making our own way in the world. Anything that threatens or denies that has to be overcome or suppressed by any means necessary. You see this impulse driving Silicon Valley, technocratic visions of the human.

These first two stories are now duking it out in the public square, with the Right telling the first story and progressives telling the second.

And again, Christians often buy into this second version of the story, even if they react against it by telling the first story. They assume secularism is the way the world is moving—despite that being very bad sociology.

The third story is a deep rejection of the first two West to the Rest narratives. Those who tell this third story are horrified by Christian nationalism and are very suspicious of the second story, realizing that science and technology haven’t liberated us, that they’ve brought us nuclear war and environmental devastation. They view the West as riven by class conflict, and deeply sexist, homophobic, and racist. They understand that the Enlightenment world also produced the Atlantic slave trade and drove imperialism.

This third version is very critical of the first two versions and their West to the Rest narrative arcs. It sees Christianity as central to the destruction the West wrought. Christianity can never be part of the solution, as it is foundational to the problem. It is precisely a Christian view of the human that generated slavery, heteropatriarchy, and an extractive view of nature. And so Christianity needs to be entirely abandoned if not abolished.

For those who tell this third story, 1492 is a cataclysm. It’s the utter destruction of other ways of knowing and being in the world, all done in the name of Christian humanism. So this third story says we’ve got to get rid of Christian humanism. That it’s only through recovering indigenous forms of knowing and being in the world that some semblance of our humanity can be recovered. Anything from the West, anything from Christianity is just destructive of what it really means to be human. And we need to entirely reject it.

DB: So in my newspaper writer style, the first group sounds like the Christian nationalists, the second group sounds like mainstream liberals. And then the third group sounds like the wokesters.

LB: That’s exactly right.

Then the fourth way of telling the story, is, I think, a true if not often-heard telling. In this version, Christian humanism is always born out of the place of encounter, particularly the place of encounter with the suffering, broken bodies of others who are not like you—the good Samaritan parable being the paradigm.

And in that version of the story, running right from the earliest period of the church where we see in the book of Acts these extraordinary communities of difference coming into existence. The New Testament portrays multi-generational, multi-ethnic communities of folk from every walk of life as the picture of realized humanity.

In this fourth way of telling the story of Christianity, there isn’t a sacred language. Some might say Latin was, but it wasn’t. The gospel can only really be heard in dialect. It’s not like Islam, where you have to learn classical Arabic to hear the word of God. In Christianity there’s always a move to translation. There’s no single sacred centre. There is no Mecca or River Ganges. The centre of Christianity is always moving. It might be Jerusalem. It might be Rome or Constantinople. It might be London or Amsterdam. It might now be Lagos or Nairobi. It’s always moving around. No culture can claim to represent the true form of Christianity. Christianity is always an intercultural, polyglot religion.

And so in that sense, you discover your humanity and true faithfulness through encountering difference. You can only truly hear the word of God through going outside of what’s already considered to be Christian.

A good figure here is Olaudah Equiano, who wrote this very influential narrative in the eighteenth century about being enslaved. Some read him through the lens of the third story, interpreting him as a dupe of Western colonialism or as embodying the tragic loss of indigenous ways of knowing and being. But I think that is a mistake. He neither views his home indigenous culture nor Western culture in idealized terms.

His encounter with Christ and with Europeans leads to a double conversion. He’s not just converted to Christianity. He’s also converted to abolitionism. He discovers himself in Christ as fully human, and through that conversion he is converted to the cause of abolishing all forms of slavery, including what some might say were the more benign forms of slavery in his home society of Igbo, in West Africa, as well as the industrial-scale versions of the plantation economy.

In his narrative, he’s the true Christian and the true human. So when he encounters the European slave traders on their slave ships, they are the true savages, and despite what they say, they are not real Christians. He also figures himself in the text as a new Paul. He’s an apostle calling others to discover both Christ and their humanity in their encounter with him through reading his story. And it worked for many. His story was a key text in the development of the abolition movement, which historians see as foundational to modern humanitarianism.

His story points to a key dynamic in the fourth version of the story: You can’t know what it means to be human if you are locked in your own culture. You have to constantly de-centre your culture in order to re-centre Christ, and therefore discover what it really means to be human. And you can only do that by going out from your culture and what you consider home through forms of encounter. That version of Christian humanism, and that story of Christianity emerging through cross-cultural encounter and intimacies born of intercultural exchange, is a fourth and I think truer way of telling the story of what Christian humanism is about and what it represents.

DB: So obviously I find the first three stories unattractive, and I want to find the fourth story attractive. Perhaps I’m reading things into it, but as you were talking, it strikes me that the fourth story is not just a form of multiculturalism because there actually is a gospel at the centre. In other words, it’s not, “You look at my culture and I’ll look at your culture and we’ll be anthropologists together.” There is something transcendent that is universally human. And then the second thing I find attractive in this story is that it’s not a rejection of individualism in order to revert to cultural tribalism. It’s a transcendence of individualism into a loftier view of what is universally shared by all people.

LB: It’s not multiculturalism, and neither is it relativism. You are trying to discover the truth—the truth of the gospel and the truth of what it means to be human. But you cannot do so alone. You can only do that through encountering others. And it’s not multiculturalism as in a politics of recognition: “I’ll learn a bit from you and you learn a bit from me, or we just need to recognize where each other’s from.” Instead, it’s, “We all need repentance.” All cultures are full of sin and idolatry and oppression. All have brutal histories that need transformation. And all have gifts to share. And it’s contributory. It’s a contributory logic, not a logic of recognition.

In the multicultural story, I just have to recognize you, whatever your identity is. So there’s no move toward a reciprocal mutual relationship. You can have recognition without a common life. Diversity without intimacy.

In the Christian-humanist version, I’m looking to learn from you. In fact, I can’t truly understand what it means to be human without receiving the gift of who you are. But it’s in the name and service of forming a shared life, forming a common life together, through which all may flourish. It’s not you flourishing in your enclave and me flourishing in my enclave. We can only truly flourish when we each contribute our gifts. When we are each mutually responsible for and in fellowship with each other.

That’s where Christian humanism properly understood pushes against both cultural triumphalism and cultural relativism. It asks, How do we engage in this shared political, economic, and social way of life called humanity? A way of life we can only discover together. No one has a monopoly on truth, but there is a truth to find. So, to use a horribly technical term, it’s at once ontologically realist—there really is a truth to discover—and epistemologically relative—knowing it is a hard struggle and my own knowledge is fallen and finite, and so I need others not like me to know it. I need a dialogue of wisdoms not multicultural recognition.

DB: How does one concretely live that out? I ask because it strikes me as a very important message for the church in the West to hear.

LB: I think there are myriad ways to do it. Let me take a concrete example of a contrast, in this case, between the church’s response to euthanasia and the church’s response to abortion. The church’s response to euthanasia has been a deeply Christian-humanist project. Dame Cicely Saunders, a Catholic doctor, saw what was happening in the 1950s. She saw the anti-human tendencies of modern medicine through its interventions in keeping people alive beyond what was really humane. And how this was being driven by the demand to further advance technology and science and so realize an anthropocentric understanding of humanity. She saw how this technological advance was creating all sorts of problems. And so she thought, well, what constitutes good care for the suffering and dying? How do we treat them as fully human in their dying when they’re suffering?

And Saunders does two things. She resuscitates the hospice as a form of care. She recognizes that we can’t keep perpetuating the science-and-technology project of keeping people alive at any cost. That that approach actually becomes inhumane at a certain point. She sees, in a sense, the poverty of the second way of telling the story, which sees no limits to human intervention and therefore ends up becoming monstrous. So she recovers hospice care and invents palliative medicine as a new form of medicine. In that gesture, for me, Saunders deeply embodies the Christian pattern that the first word has to always be a word of Yes.

God in Jesus Christ’s first word to a sinful and suffering humanity is Yes. And then in the light of that Yes comes a No. In Saunders’s case, her affirmative word, her constructive response, was hospice care and palliative medicine. And they are open to anyone. You don’t have to be Christian. Anyone of any philosophy or religion can come touch, see, taste, and smell what this vision of good care for the suffering dying involves and how it embodies treating even the most frail and fragile as having dignity and worth. It’s a human gift. But in saying Yes to this form of care, Saunders says no to euthanasia. Only in the light of the initial yes was the no to euthanasia said.

Now, contrast that with the abortion debate. It’s a similar set of questions: What constitutes good care for the unborn? And there’s a deep concern to uphold the dignity and worth of embryonic life. That’s fundamental. So it’s a deeply humanistic concern. But the first word from many in the church on this issue was No. There was no constructive alternative. There was no deep investment in prenatal care or in welfare structures for women. No attempt to address the material conditions that might lead someone to want to have an abortion. None of that was done. It was just a rather legalistic and procedural answer. And an answer in which the first word was No, not Yes. Not surprisingly, many said, “Get lost.” And so we have the abortion wars still running on the same track. It’s all about control of the Supreme Court. And many of those who say no to abortion have become aligned with Christian nationalism and a civilizational project to secure family, faith, and flag.

So in practice, this fourth version of Christian humanism takes imaginative institution-building. It demands attending to the material and social conditions by which people live: Does their work, pay, air quality, housing, and so on enable them to flourish as humans? What alternatives can be created in the face of that which brings suffering, that which brings oppression, that which demeans and desecrates human life? And that’s the lesson the church is really failing at.

That incarnational vision of human flourishing in all its dimensions, that’s central to Christian humanism. And it should be manifested through political and economic initiatives such as credit unions and cooperatives, hospices and homes for the homeless, community organizing and community gardens. It is fully human and therefore fully material, and therefore fully enmeshed in the social, economic, and political work of cultivating the flourishing of not just humans but all creation, beginning with and prioritizing the needs of the least, the lost, and the last. But it’s too often lost in the name of a gnostic, disincarnate “statement of faithery” that’s increasingly aligned with nationalist projects of defending family, faith, and flag, rather than proclaiming and embodying an inhabitable good news. We are actually losing the soul of the church.