W

When a Nation, led to greatness by the hand of Liberty, and possessed of all the glory that heroism, munificence, and humanity can bestow, descends to the ungrateful task of forging chains for her Friends and Children, and instead of giving support to Freedom, turns advocate for Slavery and Oppression, there is reason to suspect she has either ceased to be virtuous, or been extremely negligent in the appointment of her rulers.

Be not surprised therefore, that we . . . should refuse to surrender them [the rights of men and the blessings of liberty] to men, who found their claims on no principles of reason, and who present them with a design, that by having our lives and property in their power, they may with the greater facility enslave you.

—Letter to the People of Great Britain from The Delegates Appointed by the Several English Colonies (1774)

This, for the purpose of this celebration, is the 4th of July. It is the birthday of your National Independence, and of your political freedom. . . . They [your fathers] went so far . . . as to pronounce measures of government unjust, unreasonable, and oppressive, and altogether such as ought not to be quietly submitted to. . . . Feeling themselves harshly and unjustly treated by the home government, your fathers, like men of honesty, and men of spirit, earnestly sought redress. . . . But . . . the British Government persisted in the exactions complained of. The madness of this course, we believe, is admitted now, even by England; but we fear the lesson is wholly lost on our present rulers.

—Frederick Douglass, “What, to the Slave, Is the Fourth of July?” (1852)

This is a noteworthy year in the history of America. The news is tense with the January 6 hearings, the reversal of Roe v. Wade, escalating racial tensions, increasing events of domestic terrorism, and the steady warming of the earth. But beneath these headlines lies another inflection point: The 246 years that most white Americans have enjoyed “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” as stated in the Declaration of Independence stands as a counterpoint to the 246 years that chattel slavery formally existed in this country (using the year 1865, the year in which the last enslaved African American community learned of their emancipation from slavery, rather than 1863, the year in which the Emancipation Proclamation was actually signed).

In the fifteenth century, Europeans fled Europe citing the oppressive policies and practices of the British government. It was likely no rhetorical accident that the complaints Frederick Douglass raised in his 1852 speech “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?” parallel those made by the delegates of the English colonies seventy-eight years earlier. But of course the conditions under which people of African descent survived and died under American chattel slavery far exceeded, in scope and horror, the treatment of Europeans under the British government. And yet somehow, despite the moral bankruptcy, spiritual hypocrisy, and excessive human cruelty to which they were subjected, people of African descent understood and retained an understanding of their full humanity, worth, and equality among all human beings before God.

How did they do this? What was at work such that those struck down refused to be destroyed?

(En)slave(d) Narratives as Primary Source Material

The first-person recorded testimony of the lives of formerly enslaved people of African descent are commonly known as “slave narratives.” I prefer, however, to use “enslaved narratives,” as this nomenclature reflects the crucially human nature of the situation. Seen through the lens of theological anthropology, I hold the conviction that no human being is ontologically or inherently a slave. “Enslavement” is rather a condition involuntarily imposed on one individual by another. But to respect and engage the literary genre, I will, when appropriate, still use the phrase “slave narrative” here.

No human being is ontologically or inherently a slave.

It’s important to note two basic things about the genre. First, one of the primary purposes of the “slave” narrative was to support and advance abolitionist efforts. Not only did enslaved and formerly enslaved individuals write of the cruelties of their experiences in chattel slavery, but they would also explain and argue against the moral and spiritual unjustness of slavery. These narratives would become important tools used in the various stages of abolishing slavery, including the international slave trade, colonial slavery, and then, finally, US slavery.

It is also worth noting that there are two types of “slave” narratives: those that were formally produced and published for mass distribution, and those that were the recorded testimony of individuals who had been enslaved. Most of us are familiar with the written narratives of Harriett Jacobs, Mary Prince, Briton Hammon, and Frederick Douglass. But the twentieth century brought recording technology, and with it, the opportunity for first-hand oral accounts of the experience of being enslaved oneself.

[sonaar_audioplayer artwork_id=”” feed=”https://comment.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/service-afc-afc1940003-afc1940003_afs03975-afc1940003_afs03975a.mp3″ feed_title=”Interview with Uncle Billy McCrea, Jasper, Texas, part 2 of 2. Jasper, Texas, 1940.” player_layout=”skin_float_tracklist” hide_progressbar=”default” display_control_artwork=”false” hide_artwork=”false” show_playlist=”false” show_track_market=”false” show_album_market=”false” hide_timeline=”false”][/sonaar_audioplayer]

[sonaar_audioplayer artwork_id=”” feed=”https://comment.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/service-afc-afc1950037-afc1950037_afs09990-afc1950037_afs09990a-1.mp3″ feed_title=”Interview with Fountain Hughes, Baltimore, Maryland. Baltimore, Maryland, November, 6, 1949.” player_layout=”skin_float_tracklist” hide_progressbar=”default” display_control_artwork=”false” hide_artwork=”false” show_playlist=”false” show_track_market=”false” show_album_market=”false” hide_timeline=”false”][/sonaar_audioplayer]

These records are just a few of the accounts of formerly enslaved African Americans that President Franklin D. Roosevelt commissioned through the Federal Writers’ Project in 1935. In an effort to boost employment during the Great Depression, the project hired librarians, historians, and researchers to interview these individuals about their experiences in the oppressive system of chattel slavery in the United States. Over twenty-three hundred of these interviews were recorded live and reflect the dialect of those formerly enslaved individuals who did not have the experience of formal education.

[sonaar_audioplayer artwork_id=”” feed=”https://comment.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/service-afc-afc1941018-afc1941018_afs05091-afc1941018_afs05091b.mp3″ feed_title=”Interview with Alice Gaston, Gee’s Bend, Alabama, 1941.” player_layout=”skin_float_tracklist” hide_progressbar=”default” display_control_artwork=”false” hide_artwork=”false” show_playlist=”false” show_track_market=”false” show_album_market=”false” hide_timeline=”false”][/sonaar_audioplayer]

[sonaar_audioplayer artwork_id=”” feed=”https://comment.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/service-afc-afc1984011-afc1984011_afs25659-afc1984011_afs25659b.mp3″ feed_title=”Interview with Susan A. Quall, Johns Island, South Carolina, May 16, 1932 (part 2 of 2)” player_layout=”skin_float_tracklist” hide_progressbar=”default” display_control_artwork=”false” hide_artwork=”false” show_playlist=”false” show_track_market=”false” show_album_market=”false” hide_timeline=”false”][/sonaar_audioplayer]

Of course no story, whether first-hand or not, is communicated outside of an existing framework of power. The first-hand accounts of the history and horror of American chattel slavery were often questioned, if not outright dismissed. Some believed that enslaved and formerly enslaved African Americans did not have the requisite literacy to produce these narratives. Others charged that the enslaved and formerly enslaved were “unreliable historical witnesses.”

Still, despite the obstacles and falsifying frames, the narratives we have reveal a remarkably sustained conviction on the part of the enslaved person that despite the body-, mind-, and soul-crushing reality of enslaved life, she was still a wife and daughter, he was still a father and brother. They were still human. Despite every attempt to thumbprint their souls and psyches with a subhuman consciousness, enslaved people defied the shadow and clung to a truer reality.

Here’s a passage from Negro Petitions for Freedom, sent to then governor of Massachusetts Thomas Hutchingson in June of 1777:

Petitioners apprehend we have in common with all other men a naturel right to our freedoms without Being depriv’d of them by our fellow men as we are a freeborn Pepel and have never forfeited this Blessing by aney compact or agreement whatever. But we were unjustly dragged by the cruel hand of power from our dearest frinds and sum of us stolen from the bosoms of our tender Parents and from a Populous Pleasant and plentiful country and Brought hither to be made slaves for Life in a Christian land. Thus are we deprived of everything that hath a tendency to make life even tolerable.

And here is Mr. James Singleton, formerly enslaved in Mississippi: “I was glad to be free ’cause I don’t b’lieve sellin’ an’ whuppin’ peoples is right.”

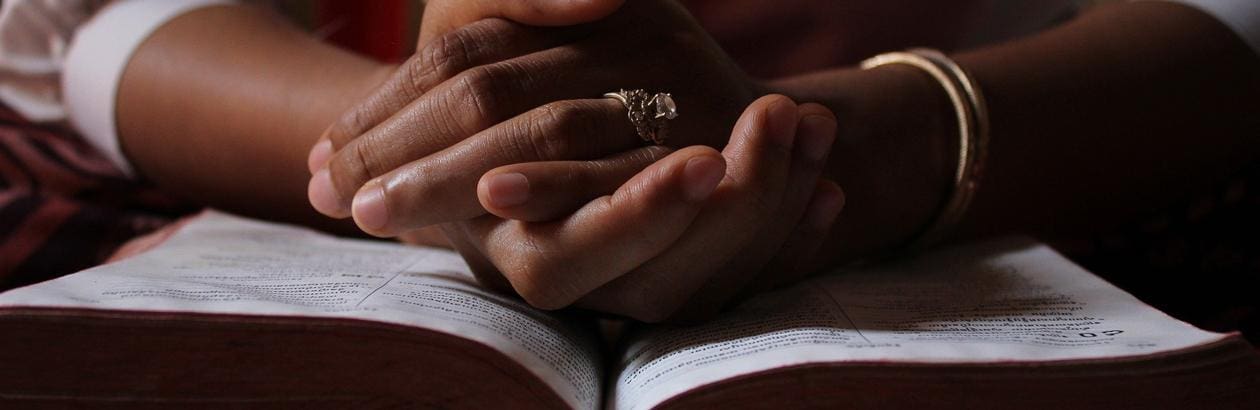

Even amid distrust of white people and the government, enslaved and formerly enslaved people knew their stories mattered and were worth recording and being preserved. The physical, psychological, and spiritual brutality of chattel slavery could not cow the conviction that they had inherent dignity and worth. Despite being interrupted and controlled in every possible expression of agency—psychic, interpersonal, cultural, and religious—the enslaved people asserted their humanness by choosing transcendence. One powerful expression of this assertion was the practice of prayer and worshipful song.

Singing New Songs in a Strange Land

Most Americans are familiar with the aesthetic of the Negro spirituals coming out of the enslaved experience, one that has since informed jazz, the blues, even contemporary folk music. But there is a quiet assumption at work that is not quite right—namely, that this is originally to the credit of the white man’s Christianity that enslaved persons were forced to adopt. Yes, the preaching of Jesus’s salvation had a decisive impact in the lives of the enslaved, but enslaved Africans were not a tabula rasa when they arrived in the New World. They brought their practices with them, and many enslaved Africans were Christians before they were taken from the African shores. As M. Shawn Copeland writes in Knowing Christ Crucified: The Witness of African American Religious Experience, “Christianity did not exhaust black religious faith or religious practices or aesthetic sensibilities. Rather the enslaved people shaped and ‘fitted’ Christian practices rituals, symbols, myths, and values to their own conditions, experiences, expectations, and needs.”

By the rivers of Babylon—

there we sat down, and there we wept

when we remembered Zion.

On the willows there

we hung up our harps.

For there our captors

asked us for songs,

and our tormentors asked for mirth, saying,

“Sing us one of the songs of Zion!”

How could we sing the Lord’s song

in a foreign land?

Mr. Jacob Branch, a formerly enslaved man from Texas, testifies to this experience of Psalm 137. Saying in one of the Federal Writers’ Project recordings, “De folks in de big house use com’ down to de’ quarters on Sattidy nights an mek’ us sing.” Enslaved people in Mississippi had similar experiences, as Mr. Tom Wilson recounts: “I ‘member Mis Nancy an’ white folks ‘ud set out thar of an evenin’ an’ mek us li’l cullud chullun dance an’ sing an’ cut capers fer to ’muse ’em.” Thousands of years after Psalm 137 was written, both Mr. Branch and Mr. Wilson echo the experience of being enslaved in a foreign land and one’s captors demanding the exactment and exploitation of your cultural practices for their entertainment and amusement. Like the psalmist, both Mr. Branch and Mr. Wilson are keenly aware of their lack of agency to refuse, to say nothing of the lack of regard for them or their culture.

While plantations varied, enslaved persons were generally permitted to sing in three locations: the fields, the brush arbors (a.k.a. hush harbors), and the quarters in which they lived. The motifs about which they sang varied, both biblically and existentially. Sometimes they would sing about freedom. Sometimes they would sing about God’s divine justice. Sometimes they would sing about heaven. Always, singing was a powerful practice whose lyrics communicated the enslaved community’s self-understanding as a people with whom God co-laboured and created. As Dwight N. Hopkins writes in Down, Up, and Over: Slave Religion and Black Theology, “The sacred power of the singing word . . . the divine gift of potent song . . . emanated from loftier heights of a sacred horizon. . . . Thus the revelation of divine lyrics and holy rhythm implanted in the aesthetic harmonizing of beautiful dark tongues signified the co-laboring exertion of God and humanity in the reconfiguration of the black self.”

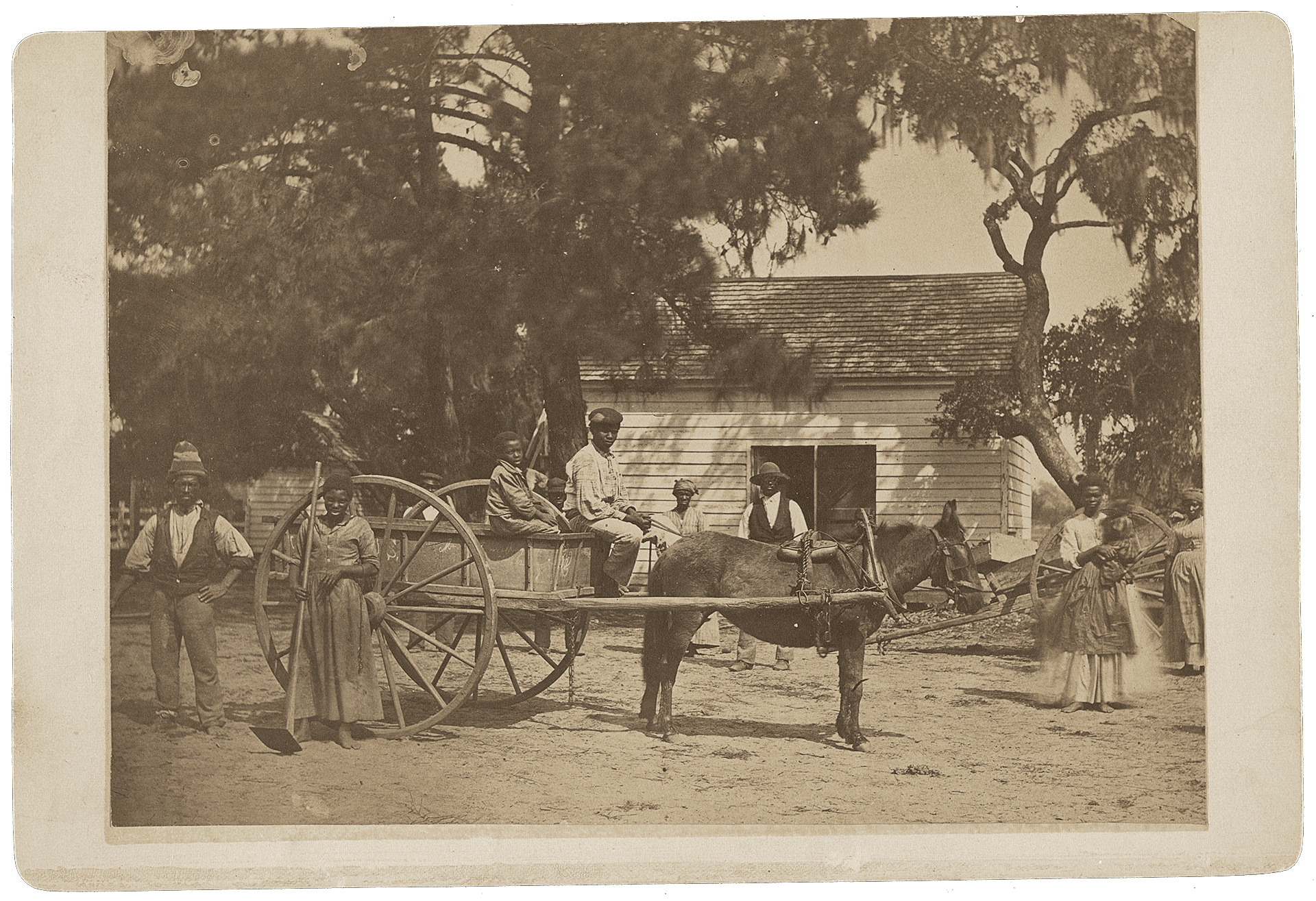

Edisto Island, South Carolina. 1862.

You see this right away in the biblical hermeneutic. Enslaved people of African descent identified with the Israelites of Exodus, and the narrative arc figured prominently in their faith and worship life. They believed that, like the Israelites, they were God’s chosen people and that they would be delivered from the cruelty of enslavement and oppression in the “strange land” of America.

Singing was a powerful practice whose lyrics communicated the enslaved community’s self-understanding as a people with whom God co-laboured and created.

Rev. Reed, formerly enslaved, bears witness to this reality in his testimony: “Some of them old slaves composed the songs we sing now. God revealed it to them.” Similarly, Mr. Jacob Branch of Texas states, “I uster knowed lots of spiritual songs but I can’t reckileck dem now. Spiritual songs dey come through visions.” Both gentlemen are bearing witness to an understanding that they have co-laboured with God in ways that also benefited them. The significance of this belief cannot be overstated. In a context in which enslaved people worked for the enslavers (sans enslavers’ help or labour) to produce goods and provide services that benefited the enslavers, to partner with God in the work of co-creating songs communicated a dignity and worth from God that the enslaved had yet to experience in the strange new world. In other words, the formerly enslaved person was testifying not only to being known, seen, and valued by God but also to the experience that God had tangibly partnered with them to create a new thing.

Hopkins also notes that “in the surreptitious gatherings of enslaved African American worship, black chattel proclaimed their faith, predicament, and hope through song.” Ms. Susan Snow of Meridian, Mississippi, recalled a song that was a customary part of the funeral rite on the plantation on which she was formerly enslaved.

She plead her cause in de wilderness

in de wilderness (2x)

She plead her cause in de wilderness

An’ den I’m a-goin home.

(Chorus) Den I’m a-goin home (2x)

We’ll all make ready, Lawd

An’ den I’m a-goin home.

She plead her cause in de wilderness

in de wilderness (2x)

She plead her cause in de wilderness

An’ den I’m a-goin home.

In spite of the fact that enslaved people of African descent were living in a strange land (wilderness) among people not only who were not their kinfolk but also who treated them as possessions stripped of dignity, agency, and voice, enslaved people still believed that there was a God who heard them, a God to whom they could plead their case in prayer. And they prayed with confidence, trusting that even if they didn’t experience freedom and home again in this life, there was an eternal place for them that was home.

This is not to suggest that faith in God anesthetized the enslaved community from the physical and psychological tortures that the brutalities of chattel slavery visited on them. While faith helped enslaved people to sing through the pain and the dissonance and helped them to “hold on, sing on,” and “pray on” just a little while longer, they also bore witness to the horrors out of which some of those songs were forged. In his Federal Writers’ Project interview, Mr. Elijah Cox stated,

Forget now and forgive has always been my guide.

Fort [sic] that’s what the Golden Scripture says.

But my memory will turn ’round back to when I was tied down

and for them we’ll weep and mourn.

For our souls were not our own,

In those agonizing cruel slavery days.

In enslaved communities, the function of song was beyond the expression of “their faith, predicament, and hope.” Songs were also vehicles for communicating information among the enslaved community. African oral culture and music had often fulfilled this function, so it was only natural that songs on the slave plantation would become subversive modes of communication. Enslaved people would sing coded language so that the enslavers would not know what was happening within the enslaved community. Messages might alert fellow slaves that an enslaver or overseer was coming or looking for someone, that there would be another trip on the Underground Railroad, or that there was going to be some type of religious service. Mr. Wash Wilson recalls it this way:

When de [negroes] go round singin’ “Steal Away to Jesus,” dat mean dere gwine be a ’ligious meetin’ dat night. De masters . . . didn’t like dem ’ligious meetin’s, so us natcherly slips off at night, down in the bottom or somewhere. Sometimes us sing and pray all night.

And yet there were plantations where singing was not permitted anywhere. Some enslavers were cruel for cruelty’s sake. Physical and psychological abuse was trotted out with abandon, but some would go even further and withhold permission to engage in the very faith practices that were sustaining the enslaved people’s spirits and bodies. Mr. Gus Clark of Mississippi testified to this spite in his Federal Writers’ Project interview:

My Boss didn’ ’low us to go to church, er to pray er to sing. Iffen he ketched us prayin’ er singin’ he whupped us. He better not ketch you with a book in yo’ han’. Didn’ ’low it. I doan know whut de reason was. Jess meanness, I reckin.

So many enslaved people kept the prayers and songs in their hearts. Ms. Millie Ann Smith of Texas recalled the hidden ubiquity of the life-sustaining melodies in this way:

The white fo’ks had a chu’ch four or five miles off the place. Precious little we went as Master Trammel’s fo’ks only went on “big meeting” days. We slipped off and had prayer meetings and prayed for ourselves but darnsn’t let the white fo’ks know ’bout it. We hummed our religious songs in the fiel’ while we was wo’king. It was our way of praying for freedom.

Enslaved people were introduced to a brand of Christianity that was diametrically opposed to who they knew God to be and who they knew they were, in and before God.

Labour and Freedom, Singing and Praying

Shortly after the arrival of Europeans on the shores of what for them was a new world, the irreconcilable difference of enslavement and liberty began to take deep root in the soul of the nascent nation. This irreconcilable difference was codified in local and then national (constitutional) documents. The irony was that this new nation was guilty of that which it indicted its homeland of—“forging chains . . . instead of giving support to freedom”—itself becoming an advocate for and beneficiary of slavery and oppression. Faulty philosophical, biblical, and theological arguments were construed to uphold and defend a morally indefensible system. However, none of these arguments persuaded those who were enslaved, the people of African descent forcibly and often violently taken from their homeland, that they were who their enslavers said they were. They were introduced to a brand of Christianity that was diametrically opposed to who they knew God to be and who they knew they were, in and before God.

And so, in the midst of enslavement, oppression, cruelty, and harsh labour, enslaved people of African descent made a world for themselves. They made a world with values and ethics countercultural to the world in which they were enslaved. They understood that the gospel had been perverted, and the governmental and legal systems had been contorted for the benefit of some and the bondage of others. People of African descent were clear that it was the laws of this “new world” (eventually “the laws of America”), but those laws were not godly. So they adapted and adopted beliefs that affirmed who they knew they were as fully human beings who had divine dignity, worth, and value, and who they knew God to be: a liberating God of love and justice who abhorred evil and loved good and who would eventually deliver them from their predicament of bondage and evil.

Their theology would thus emerge in the language of their faith and their prayers and their songs that was reflective of both their predicament and their hope. Praying and singing as they laboured in fields and homes, from sunup to sundown, they prayed for freedom and they sang about freedom. Their prayers became songs, and their songs an act of prayer. As North African bishop Augustine of Hippo is credited with saying, “Whoever sings, prays twice.”