T

A Holy Instinct

Those who know me best will tell you that my first instinct is almost always the wrong one. This was true as a child, and it is, I am sorry to say, largely true today. But of those few right instincts that I have had, two of the very best were these: the instinct to marry a green-eyed, brown-skinned girl with a brilliant mind and a Southern lilt—and the instinct to defer graduate school and spend our first year of marriage on a five-hundred-acre farm in the South Carolina Low Country.

When we shared the news of our decision, many of our friends and family were confused. For months my wife and I had talked excitedly about moving away and starting school together. More than once we road-tripped west to visit the campus and imagine our new life there. We were even known to wear school swag and leaf dreamily through the course offerings to come. And yet somehow, seemingly out of nowhere, our plans shifted. Eschewing the long-anticipated life of urban libraries, we embraced the unknown life of a farm. My father, to no one’s surprise, summarized the general mood with his own response. Closing his eyes, he simply shook his head and walked away muttering something about the general uselessness of Thoreau.

Undeterred (a condition that also persists), two weeks before our wedding I loaded my meagre belongings into my even more meagre car and drove south. After several hours of pulling over to compare maps with hastily scrawled directions, I finally made my way out into the country and, sheltering my eyes from the afternoon’s last light, found the driveway’s sandy entrance. I turned in, slowed to a stop, and stared in silence at the world around me.

Words fail, but here is an attempt to describe the sight: The driveway, in that distinctive way of the Low Country, stretched out long and straight before curving gently into thicketed shadows. Massive live oaks, their powerful branches garlanded with Spanish moss, stood in sentried rows along each side and bowed toward one another in a regal arch. Peacocks (yes, peacocks) called out from the branches and then settled in to roost. On either side, late summer fields stretched golden into the distance, eventually fading into darkling groves of pine. Though still at the beginning of the driveway, I turned off the car and climbed slowly out into the thick evening air—skin tingling—steadied my breath, and began to walk.

I was not in any way prepared for the life that I was walking into. Apart from stories about my family’s rural past in the Appalachian foothills and the occasional Saturday morning foray to a farmer’s market with my grandmother where I would watch her squeeze tomatoes and smell cantaloupe, I knew virtually nothing about farm life. What I knew, in fact, was its opposite: I knew bicycling through the burbs, microwaving Hot Pockets after school, and filling every frightening silence with the sounds of a Walkman. I’m not sure that I had ever walked an actual field. I’d certainly never seen a peacock. And the few woods I had known were places with an undertone of darkness, places where I built forts to hide from enemies real and imagined, smoked reeds from the creek bank, and drank wine coolers from a box. What I knew, in other words, was less like A River Runs Through It and more like Stranger Things.

Yet even as the old fears crept in, standing in that driveway, something new—something like enchantment, which is a form of hope—began to grow inside of me. So after retrieving my car, unloading my boxes, and checking every closet twice for traces of the Demogorgon, I sliced some of the summer’s last peaches, sat down on the steps of the now shadowed porch of the old farmhouse, and listened as the forest came to life.

The farm, known as Wantan, came into the owner’s family in 1812. Originally much larger, over the years sections of it had been sold off to children and cousins, until a new community grew up in the fields. As is the way of farm communities, these folks bore each other up over the centuries. They pooled their labour, shared their produce, married off their children, and, when the time came, laid one another in the soil. The house we inhabited, a 1930s three-bedroom, was the third on its site, the previous two having been destroyed by fire. It sat at the end of the driveway, sheltered by looming oak, Japanese maple, and formidable hedges of holly. It had a wide porch, a leisurely swing, and a screened front door that squeaked in just the way you imagine it would. The yard behind us, which held a workshop, a writing shed, and a smokehouse, drifted slowly into a fence line with fields and pine groves stretching into the distance beyond. And in a beautiful old home just through the trees lived the Whiteheads, the family who for the past two centuries had made their life with this land and now welcomed us so freely onto it. Two weeks after that first night on the porch, it was here—in this house, with these people, embedded in these fields, and surrounded by these forests—that we began our married life together.

I spent most of that year sowing myself into the soil of that place, sowing the soil of that place into myself.

It will likely not surprise you to hear that I was, as they say, “all in.” Though I had a job of sorts, the truth is that I spent most of that year sowing myself into the soil of that place, sowing the soil of that place into myself. Most weekday mornings I set off with a journal, a book, and a bottle of water to wander the woods and document the trees and the birds. In the evenings I set a flowering table in the yard for our supper. After nightfall, I walked by headlamp into the farthest field where my friend Scott, owner of the local outdoors store, tried in vain to teach me the constellations of the night sky. I collected abandoned nests. I slid silent canoes into black water. I pulled striped bass from the lake. I followed a meandering boardwalk hundreds of yards to a bench in the swamp where I sat and watched for the great heron to take flight. I spent my year, as Aldo Leopold once put it, watching “the one hundred dramas of the little woods and meadows.”

Lest I beguile both you and myself, however, I should say that I also spent the year more or less making a fool of myself. Taking wrong turns in the woods. Falling out of canoes. Casting fishing lines into trees. Running from harmless snakes. Acquiring poison ivy in secret places. Watching in humiliation as my wife, during a meal of wood duck I’d freshly killed and prepared, took little pellets of birdshot out of her mouth and lined them up neatly on her plate. I even began to affect a Low Country accent. Yes, I did that.

And through it all, perhaps above all, I read. Lewis and Clark’s descriptions of the terror of the Rockies and the fecundity of the plains. Thoreau’s ecstatic musings on Walden Pond and his lecture “Walking.” William Bartram’s revels as he travelled through the “incomparable lande” of the Carolinas. John Muir’s tale of his one-thousand-mile walk from Kentucky to the swamps of Florida. Annie Dillard’s rapturous narration of her pilgrimage on Tinker Creek. Norman Maclean’s melancholic reflections on his Montana childhood. I read essays on astronomy, histories of wetlands, catalogues of birds, and instructions on the navigation of rivers. And on cold winter mornings, as the world woke around me, I sat in a deer stand and read nature poets—mostly Romantics—such as Emily Dickinson, Mary Oliver, Robert Frost, and Archibald Rutledge. I confess even to Wordsworth.

In retrospect I see that this list was fairly limited culturally. And I was years away from meaningful reflection on the blood and sorrow buried in the soil of a Southern farm. In subsequent years I discovered a vast storehouse of nature writing by women, Native peoples, and African Americans that opened my eyes to both a greater beauty and a greater sorrow in the American landscape. Even so, these early books were the beginning of my ecological education. They taught me—for the first time in my life—to see the soil, the plants, the animals, the rivers, the very sky. And not only to see, but to cherish. They opened a world of loveliness to me, and they gave me language for that love. A year later, when my wife and I loaded our things on a truck, pulled out of that driveway for the last time, and finally began to make our way west toward graduate school, I gave voice to that love through tears.

These books taught me—for the first time in my life—to see the soil, the plants, the animals, the rivers, the very sky. And not only to see, but to cherish.

For a long time, in the public telling of the story of that year, the sheer privilege of it often led me to imbue it with the quality of whimsical surprise, as a sort of impulsive and frivolous (if delightful) departure from real life. To see it, as my late father once did, as an expression of yet another of my eccentric instincts. Recently, however, while wishing no quarrel with the dead, I confess to seeing it quite differently. Looking back on that young man now, as he walked the woods, peered into the waters, and mapped the sky, I see that what he was doing—what I was doing—was not randomly following not an errant instinct but purposefully following a holy one. The instinct to, for the first time, fully inhabit the earth.

Against the Grain

I have never got over that year spent in the fields and forests of Wantan. But neither have I ever been able to reproduce it. Like marriage itself, that first year of inhabiting the earth was largely spent getting to know its loveliness under a golden light. The work of learning meaningfully to love it under the dappled conditions of ordinary life, however, has taken a bit more effort.

Part of the reason for this is that I have never again lived with the sort of gratuitous proximity to what we call “nature” as I did that year. Two days after leaving the farm, my wife and I pulled into the heart of St. Louis and moved our things into a tiny urban apartment surrounded by concrete where, for the next four years, we were separated from our neighbours not by the silence of fields but by the thinnest of walls. And while we have lived in three different houses in the subsequent years—each lovely in its own way—we have nonetheless continued to live at a distance from anything approximating the rural or the wild.

Another part of the reason, however, is that literally nothing in my life has encouraged such proximity. My successive dwellings have all been in neighbourhoods built on land cleared of forests and rimmed with road. My nearly fifteen years in graduate school, for all their goodness, were similarly cloistered, largely devoted to what was breathlessly, if dualistically, referred to as “the life of the mind.” And my years as a pastor, in spite of the agricultural metaphors at the heart of that vocation, were largely spent toiling in the fields of holy words, corporate song, private pain, and institutional politics. In spite of my longing to inhabit the earth, the circumstances of my life seemed only to bear me away from it.

Even so, almost wholly against the grain of these circumstances, I continued to try; to reach back to my time at Wantan and draw—if not its daily habits—then at least its meaning forward into my days. This reaching has taken many forms. Back in St. Louis I drove an hour out into the countryside just to catch a glimpse of the Hale-Bopp comet. I volunteered to work for free in the prodigious garden of one of my professors. It was in those urban years that I came unexpectedly to love the majestic breadth of the Mississippi River basin and, thanks to regular walks through Forest Park, the mottled grandeur of the American sycamore.

In spite of my longing to inhabit the earth, the circumstances of my life seemed only to bear me away from it.

Our move to Charlottesville two decades ago, though hardly a return to Wantan, nonetheless placed the earth somewhat more within reach. Charlottesville is in many ways a frenetic city, where the young are mentored into ambitious vanity and destructive overcommitment. But its enclosure by the Blue Ridge Mountains, a natural forest, and thousands of acres of farmland means that those who long to more fully inhabit the earth have at least a fighting chance of realizing those longings.

In our early years here I walked most of the major trails and fished most of the rivers within an hour’s drive. I have, with varying degrees of success, worked to cultivate a garden at our home. I have tried my best to introduce my children to the beauty of the farmer’s market, the thrill of woodsmoke, and the mystery of the stars. For several years I spent at least one day per week working on the 750 acres of Edgewood Farm just outside of town. It was there that I learned to thin the forest to shaded pasture, soak logs full of mushroom spores, haul trout from cages for market, rescue abandoned calves from their sick mothers, and plant boxwood hedges in the spring rain. For the past three years I have maintained an almost daily practice of walks—by day and by night—through the grounds and gardens of the University of Virginia, greeting the American sycamores and sitting beneath the golden ginkgo. And perhaps above all, I have taken up work as a professional cook, learning from chefs like Tucker Yoder, seed historians like John Coykendall, and farmers from around the valley to harvest the bounties of this world and offer them to my neighbours in love.

Each of these activities is, in its own way, an attempt to honour the instincts of that young man wandering around Wantan. An attempt, even as I worked professionally to engage academic conversations regarding large-scale transformations in Western culture, to maintain a sacred space in my imagination for soil, wind, feather, and bone. The fruit of this attempt has been the slow growth of an inescapably ecological horizon to my understanding of what it means to be human. That is, of all that being human could mean, what it must always yield is that we understand ourselves and carry ourselves as members of what Aldo Leopold refers to as “the land community.”

Market colours, images by author.

A Leaf in the Table

As I have noted elsewhere, The Welcome Table is fundamentally animated by what we at Comment call “the convivial imagination.” This phrase tends to summon images of open doors, full tables, and raised glasses. May such images ever rise in the heart. But in truth, it means more than this. “Conviviality,” after all, literally means “life with.” It is therefore not first about celebration but about community, about the willed determination to live with one another and to devote ourselves to that other’s well-being. In highlighting the “ecological horizon” of humanness, I am simply suggesting that the earth itself deliberately be included in the bounds of that community, that creation be given a seat at the table. As Leopold put it in A Sand County Almanac, “All ethics so far evolved rest upon a single premise: that the individual is a member of a community of interdependent parts. . . . The ‘land ethic’ simply enlarges the boundaries of the community to include souls, waters, plants, and animals, or collectively, the land.” Conviviality, rightly understood, requires us to add a leaf to the table of our imaginations, to welcome what we call “the natural world” into the horizon of our community.

But how? For many of us, virtually everything in our lives inclines us not to expand the table but to shrink it. And this is all the more so when it comes to the earth and the crisis of our ever-deepening state of alienation from it. As I have struggled to answer this question over the past decades, I have become convinced that welcoming the world will require the deliberate cultivation of new habits in our lives, habits both contemplative and constructive.

Opening the Eyes

John Muir, the legendary naturalist, conservationist, and author, has an essay called “A Wind-Storm in the Forests.” In it he recounts a time in 1874 when he visited a friend’s small cabin in California’s High Sierra. While there, a rare Pacific hurricane came far inland, creating a furious windstorm. Rather than staying in shelter, however, Muir headed out into the storm and toward the highest ridge he could find. Once there, he climbed over one hundred feet to the top of the tallest Douglas spruce on the ridge. As the storm raged on, he clung to its highest branches and gazed down on the storm’s sweeping riot through the valley below.

Why? Because he wanted a new way of seeing the world.

Of all of the various themes found in nature writing, one of the most consistent is this: if we are to live in community with the natural world, we must begin by learning to see it. As Annie Dillard puts it in A Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, “It’s all a matter of keeping your eyes open.” Strange as it may sound, many of us live lives that actually blind us to the world. I continue to marvel at how easy it is for me to simply disappear into both labour and leisure without the faintest awareness of the miracles happening all around me. This kind of blindness, with all of its consequences—both benign and malignant—is evidence of a failure of love.

There was a time when I thought that expositions of the Hebrew Bible’s call to dominion over the world or theological appeals to a “creation mandate” were enough in themselves to heal this broken love. I no longer think this. Over the years I have found too many of these accounts to be shelters for ignorance, functioning as vaguely theological justifications for the world’s diminishment under our hand. If our broken love for the world is to be healed, what will be required of us is attention. Like Muir and all who have come before and after him, we will need to learn to see—to see both the world and our place within it in a renewed way.

In the Christian tradition, the source of this renewed sight is the work of contemplation. The contemplative life, by its very nature, creates space for us to sit in silent attentiveness. In my own life, this work of learning to love the earth means willed contemplation of God as Creator: deliberate attention to the scriptural account of God’s relationship to the earth. It means willed contemplation of myself as creature: deliberate attention to the scriptural account of my relationship to the earth. It means willed contemplation of the earth itself: deliberate attention not simply to its spiritual meaning but also to its material forms. And it means, in the midst of each of these forms of attention, an ongoing struggle to understand what I am being asked to love, where I am failing in that love, and what the reordering of my love will require of me.

“Conviviality,” literally means “life with.” It is therefore not first about celebration but about community, about the willed determination to live with one another and to devote ourselves to that other’s well-being.

Contemplation of this sort increasingly inoculates us against the contagion of presumptuous and extractive violence that threatens at every hour to consume everything around us. Viewed in this respect, contemplation may be understood as a form of confrontation—a struggle to see in the midst of blindness and to love in the midst of neglect. Contemplation is not, in spite of popular sentiment, a movement away from the world, but a movement toward it with a deepened commitment to love.

Such contemplation is the foundation of any faithful embodiment of our ecological humanity. As Douglas Christie puts it in his essential Blue Sapphire of the Mind: Notes for a Contemplative Ecology,

This more integrated way of being has as its foundation the cultivation of a new sort of imagination, one predicated not on domination and extraction, but on something like communion, on the capacity to see ourselves simply as one part of the whole of creation. And not only to see ourselves but also to truly see the earth as a living community of which we are a part and to which we bear the obligations of love.

I confess that even with years of ecologically oriented contemplation, I continue to gaze at the world mostly uncomprehendingly. Its mysteries—particle and wave, light and shadow, birth and death—remain beyond my grasp. Even so, I am content because, as virtually all contemplative writers remind us, the point of contemplation is not comprehension. The point is the gaze. In a moment of such catastrophic blindness—ecological and otherwise—the commitment to open one’s eyes may just be the foundation of holiness.

Making a World

Like all acts of welcome, however, the work of inhabiting the earth and welcoming the non-human creatures around us into the horizon of our community is not simply a matter of sight. It is also a matter of practice. We are, after all, not voyeurs. We are lovers. And love means action. But what sort of action? What shape should the work of inhabiting the earth take for us?

Those who have begun seriously to ask these questions will tell you that the answers are not altogether clear. Part of the reason for this is the sheer complexity of the question. In our time, to speak of inhabiting the earth is—whether we intend it or not—to speak of matters biological, economic, political, and climatological. And most of us struggle to understand even one of these. But perhaps more daunting than the complexity is the sheer scale of the question. To speak of the earth is to speak of, well, just about everything. As a result, many of us feel like the best we can do is engage in some sort of fragmentary ecologism: to occasionally recycle, suffer through bamboo toothbrushes, and extol the virtues of David Attenborough.

Yet this is our work, and it is crucial both for our own integrity and for the integrity of the earth that we take it up. This last clause, “the integrity of the earth,” bears repeating. Since the middle of the twentieth century, the virtually unanimous testimony of scientists and naturalists alike is that the earth is in the midst of an atmospheric transformation whose consequences—warming weather, glacial melt, rising seas, and creeping aridity—will have profound implications for life on this planet. And not only this, such transformation is not in any respect “natural” but is wholly of our making. Further still, it will only be healed—if indeed it can be healed—by our collective action.

The point of contemplation is not comprehension. The point is the gaze.

These combined facts signify the advent of a new era in global history in which there is no part of the earth that is unaffected by human action. Jedediah Purdy, among others, refers to this era as “the Anthropocene”: the age of the human. In his extraordinary work, After Nature: A Politics for the Anthropocene, he puts it this way:

The work of inhabiting the earth, then, is in fact the work of making a world, a work that is not only faithful to the ethic of love but necessary for the future of life.

While the horizon of ecological action is by definition global, most of us ought to focus our action locally.

But how? How do we engage in a work that is at once incomprehensibly vast, dauntingly complex, and yet existentially imperative? I have come to believe that while the horizon of ecological action is by definition global, most of us ought to focus our action locally . In one respect, such a focus is born of a realistic assessment of the profound political and commercial obstacles to ecological engagement on both national and global scales. In another respect, it is a product of the recognition of our own modest capacity and our need to labour on a more manageable scale. And in still another respect, it is born of a basic belief in both the deep knowledge and the generative creativity of local communities. While local communities cannot, in themselves, solve our varied ecological crises, these crises will not be solved without them.

What form might such local labour take? My own view is that it ought deliberately to consist of four forms of action, here rhymed for the reader’s convenience.

The first of these is education. Most folks I encounter, and certainly those older than Generation Z, lack basic ecological knowledge. By this I mean both knowledge of the ecosystems of the world—soils, waters, plants, animals, skies—and knowledge about their relative health. And yet apart from such knowledge it is difficult to imagine what it might mean not only to love the earth but also to act meaningfully on its behalf. Because of this, my hope is to see communities—not least communities of faith—devote themselves to this work of education. This education will take many forms, of course, but I have found readings that orient us to the earth and to its condition to be an incredibly helpful place to begin. Of these, I strongly recommend Elizabeth Kolbert’s Under a White Sky: The Nature of the Future and Dan Barber’s The Third Plate: Field Notes on the Future of Food.

The second form of action is moderation. In this I am speaking of both the nature and the extent of our habits of consumption. Our unprecedented consumption—and the industries that it sustains—are alienating us from the land community and driving that community into various forms of crisis. This consumption takes many forms, among the most prominent of which are food, fashion, and fuel. Each of these has an extraordinary impact whose only real redress is moderation. Happily, there are both resources to instruct us in this work of reordering our loves and local communities to support us as we take it up.

The third form of action may be called cultivation. Purdy’s insight that the world we will ultimately have will be the world we make means that—whether we mean to be or not—we are all either makers or unmakers of the earth. Those who seek to embrace the ecological horizon of being human are called not simply to inhabit the earth but to rehabilitate it as we do so. At the most basic level this means giving ourselves to what Leopold refers to as “the voluntary practice of conservation on our own lands.” What Leopold has in mind here is people who, out of “an ecological conscience,” deliberately tend the small ecosystem under their care—the homes in which we live and the yards, woods, or streets that surround them. This is as elemental as it sounds: tending to the health of the soil; cultivating plants and trees that nurture one another and the birds and bugs around them; slowly converting our homes to structures that live easily and respectfully on this soil and among these plants. In short, making gardens of the lands on which we live. I understand all too well the challenge of such work of cultivation. I live in a hundred-year-old ramble of a home whose previous owners, so far as I can tell, were wholly unaware or wholly unconcerned with “the voluntary practice of conservation.” And so it has come to me. Over time this will mean different windows and doors, different forms of energy, and the slow cultivation of a horticultural ecosystem that approximates something like balance. This is the work of a lifetime. Indeed, it is the work of many lifetimes. But it is just this sort of cultivation that inhabiting the earth requires.

Last, this requires the work of legislation. In saying this I am not insensate to the anxiety produced by a sudden evocation of the political. After all, to talk about potatoes and peonies is one thing; to talk about policy is quite another. Suddenly the air leaves the room. But such talk can’t be helped. Even the barest survey of the history of land use in the Americas reveals that what ultimately shapes the well-being of the natural ecosystems on the land is the politics of the state that presumes to own it. There is no way around it: the constructive work of inhabiting the earth with love will require collective political action devoted to the earth’s interest. While most of the headline-grabbing ecological policies focus on the national or global level, the often-disregarded truth is that local policies matter greatly, and always have. These policies represent local, communal decisions about the nature and use of our water, our fields, our forests, and our non-human neighbours. And these decisions profoundly affect both local ecosystems and national discourse. As an illustration of the stakes of such local engagement, consider the leaden waters of Flint, Michigan, the carcinogenic marshlands of Louisiana’s Allee du Cancer (Cancer Alley), or the vanished mountains and eroded forests of West Virginia’s coalfields. Each of these was—as all ecological decisions ultimately will be—a consequence of the political action, or inaction, of local communities. That this is so can mean only one thing: the work of rehabilitating the earth must finally be a work of collective political will ordered toward love of the world.

This is the shape of constructive action required to inhabit the earth in love: education, moderation, cultivation, and legislation.

This, then, is the shape of constructive action required to inhabit the earth in love: education, moderation, cultivation, and legislation. It is true that the political, economic, and structural implications of such action are both many and as yet unknown. But it is only as we take up this work and collectively devote ourselves to it that we may once again become, in the wonderful words of Christie, “those by whom the world is kept in being.”

Glimpses of a Future

I left our life on Wantan roughly twenty-seven years ago. And I must confess that in spite of my efforts, I am, in many ways, still at the beginning of my struggle to inhabit the earth. I still remain captive to the limits of the ecological mores and infrastructure of my community and my nation. I still remain ignorant of so much about this world: its tides and its fields, its fauna and its forests. Just last week, for example, I spent most of the weekend trying to understand and nurture the right soil composition for lavender. When I went out to water the flower bed last evening, the browning lavender let me know that I got it wrong. I am, after all these years, still a tinkerer on this pilgrimage.

But the pilgrimage continues. And every year, at one point or another, it leads me back to Wantan. Each year of my children’s lives they have turned into that driveway, felt the car slow to a premature stop, and stepped out into the silence of those fields. Together we have walked the pine groves, with faithful farm dogs trailing behind or leading us forward. They have walked the boardwalk to the swamp and watched the great heron take flight. They have slipped ancient boats into black waters and retrieved bleached deer skulls from the banks. They have stood in the black night and gazed—under Scott’s still steady hand—into the stars. And they have sat in blankets around a fire in the forest, eating s’mores and learning stories. I have often thought of these times as visits to a lost past. And so they are; my life at Wantan is lost beyond recovery. But in truth they are more than this. They are, I pray, visits to a future when my children, too, will, in the fullness of their humanity, come to inhabit the earth.

It’s too early to say what the effect of these visits and my other ecological labours—frail as they are—will be on my children, and, through them, on the world they will inherit. But there are hopeful signs. One of my girls works at a French bakery, learning the hidden ways of wheat and cream. Another spent her summer working on a farm in the south of England and writing essays in the light of Mary Oliver and David Whyte. Still another has taken up the work of climate activism and is unnervingly adept at noting the gaps between our ecological priorities and our ecological practices. And in a few weeks’ time, my boy and I will join Scott and one of his boys for a canoe trip through the tannic rivers of the Low Country.

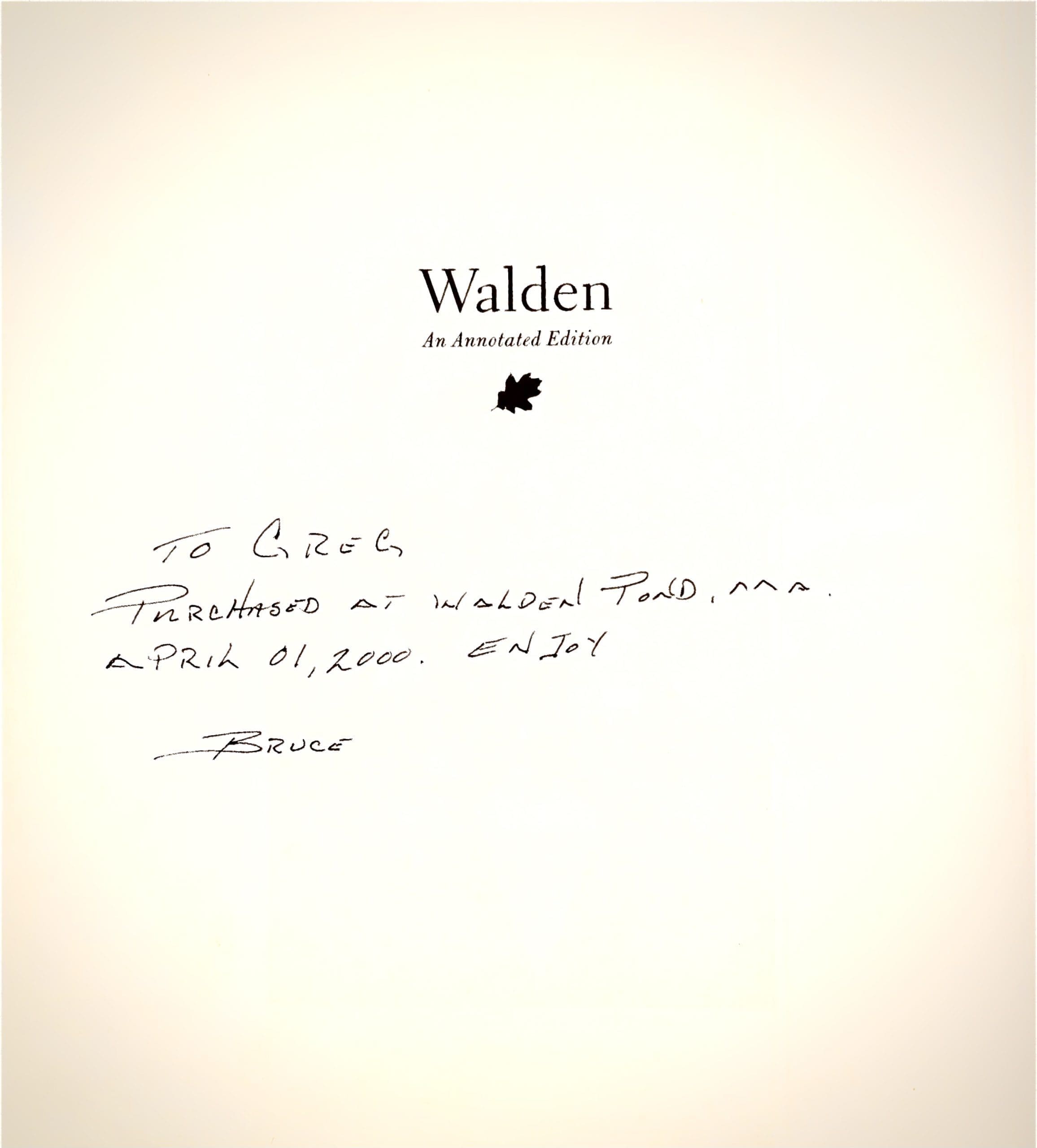

But the most hopeful of all was this: A number of years back my father came to visit me on Edgewood Farm in Virginia. As was his way, he groaned in annoyance at every thrilling vista and shook his head at my lingering eccentricity. A few days later, however, I received a package wrapped in brown paper and marked with his familiar scrawl. I sat down on our couch to open it and, having unfolded the paper, immediately laughed out loud. As my wife came in to check on me, I held up the contents with tears in my eyes. It was, of all things, an elegant hardbound copy of Thoreau purchased by my father on a clandestine visit to Walden Pond.