A

“Art raises its head where religions decline,” pronounced Nietzsche in Human, All Too Human. “Feeling, forced out of the religious sphere by enlightenment, throws itself into art.” Nietzsche was not alone. “Let us love one another ‘in Art,’” gushed the French novelist Gustave Flaubert, “as the mystics love one another ‘in God.’” In his 2003 book The Invention of Art, Larry Shiner confirmed these observations, going so far as to explain that “Art” (capital A) as we know it today is an invention of the nineteenth century meant to serve as a secular faith. And even if Pop Art desecrated the new religion, for many it is still going strong. Contemporary art is “an alternate religion for atheists,” claimed Sarah Thornton in her 2009 book Seven Days in the Art World. “Museums,” announced one enthusiast at LACMA’s fiftieth-anniversary gala, “are the temples and the churches of today.”

Admittedly this puts religiously faithful people in a strange position. Considering that artifacts from their traditions are what constitute the most beloved objects in most global museums, why should their treasures be continually exhibited as trophies for this rival god? As discussions about repatriating artifacts to their countries of origin rock modern institutions to the breaking point, should people of faith demand that their artifacts be returned as well? Should those of us who have not foolishly delegated our souls to the Smithsonian be shaking down museums today? Which is to say, should we cheer on Vladimir Putin when he liberates Andrei Rublev’s famous Trinity from its curatorial captivity to restore it to the church?

I think the answer to these questions in most cases is no, and for a simple reason. The notion that “Art” is entirely an aftereffect of the Enlightenment certainly has a lot going for it, except for one considerable downside: it is not entirely true.

Doubting Nietzsche

It is difficult for the “secular invention of art” theory to survive a reading of Katie Kresser’s 2019 book Bezalel’s Body: The Death of God and the Birth of Art. Kresser makes the case that art in fact was hatched not after the so-called Enlightenment but after the enlightening of the world that came with Christ’s resurrection from the dead. Drawing on the Danish art historian Troels Myrup Kristensen as well as Hegel, she shows how Christians recontextualized and repurposed pagan images just as much as, if not more than, they destroyed them. “Christianity,” Kresser argues, “seemed to debase and elevate the sacred image simultaneously, both disempowering it and expanding its referential scope. It was through this process that Christianity created this thing we call ‘art.’” As a result of Christianity’s triumph, “the classical idols, now considered unable to contain the gods, were no longer deserving of ‘veneration,’ but thanks to their eloquent and orderly forms, they began to demand a different sort of gaze instead.” Anyone who has taken a stroll through the Vatican Museums will find Kresser’s theory promptly confirmed. Advocates of the Enlightenment origin of art will explain the beauty of pagan statuary in this Christian setting simply by attesting to the creation of the Vatican’s Pio Clementino Museum circa 1771. But this prompts a rather obvious question: Is anyone seriously suggesting that Christians did not admire the sculptures before that? If not, how can we explain the fact that so many so-called pagan sculptures survive?

Just last year, another art historian contributed much more evidence to this thesis. In her magnificent 2022 book From Idols to Icons: The Emergence of Christian Devotional Images in Late Antiquity, Robin Jensen charts the transition from pagan idols to Christian icons. She argues for a “material turn” in the mid-fourth century when Christians began to use images devotionally. Jensen shows that there were, of course, Christians who chiselled crosses into the forehead of Aphrodite and who destroyed pagan monuments. (The destruction of Confederate statuary in more recent times might even evoke our sympathy for their zeal.) But destruction was not the only answer to the question of what to do with beautiful objects once the demons that haunted them were vanquished. Jensen argues that Christians criticized pagan idols for primarily theological, not artistic, reasons. In principle, they knew that the objects themselves were harmless. “We know that ‘An idol is nothing at all in the world’ and that ‘There is no God but one’” (1 Corinthians 8:4), wrote the apostle Paul.

One Christian alternative to destruction, therefore, was admiration. Jensen cites an amusing line from Augustine addressed to Christians who wanted to have an image of Hercules destroyed. The local proconsul tried to placate the Christians by chiselling off his beard, and Augustine advised that this was more than enough: “I think it was a much greater humiliation for Hercules to have his beard shaved off than to have his head cut off.” Jensen concludes her book by showing how wealthy Egyptian Christians refused to destroy pagan images, instead viewing them as splendid works of art; hence, her book might just as fairly be called From Idols to Icons and Art.

We could add to Jensen’s evidence. A pious Christian eunuch named Lausos amassed quite an art collection composed of pagan statuary in fifth-century Constantinople, and an equally pious emperor’s daughter named Marina boasted a rival collection. In Other Icons, Eunice Dauterman Maguire and Henry Maguire show how nude sculptures of the labours of Hercules or the sleeping Endymion enhanced the same city’s walls. Likewise, Bettany Hughes relates that statues of Aphrodite were displayed in the city baths and even outside the Senate house of this Christian empire’s capital. In short, we may have had to wait until the eighteenth century for Alexander Baumgarten to coin the word “aesthetic,” but the possibility of Christians enjoying objects for their pleasing effects alone came long before. “There was a man,” claimed that most uncompromising of desert ascetics, John Climacus, “who having looked upon a body of great beauty, at once gave praise to its Creator, and after one look was stirred to love God and to weep copiously.”

Infiltrating the Fortress of Formalism

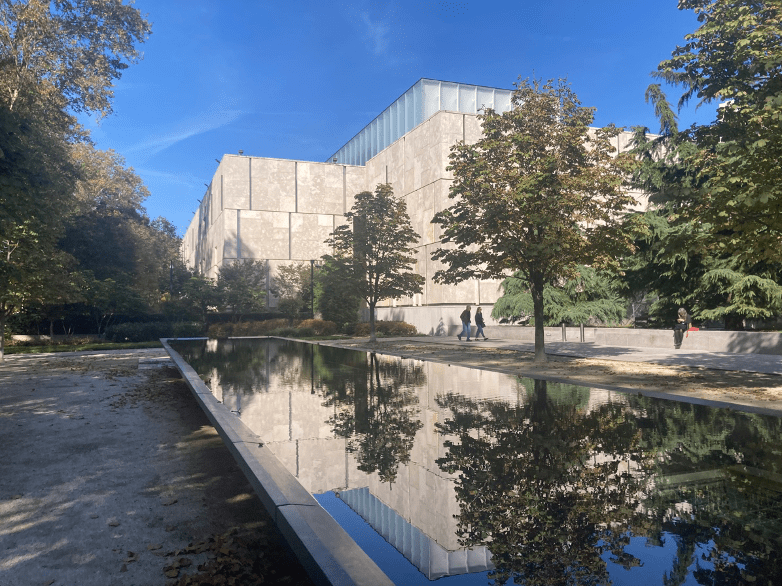

To discover whether this “Christian invention of art” theory is true, I decided to test it. Not at the Vatican Museums, the Met, London’s National Gallery, or the Louvre (where it would be proved too quickly), but at the most famous institutional bastion of aesthetic appreciation, Philadelphia’s Barnes Foundation. As art-goers worldwide well know, the Barnes Foundation is a shrine to the notion that objects should be considered primarily (if not exclusively) for their formal, aesthetic properties, leaving onetime functional purposes, whether to enhance a Christian liturgy or affix a barn door, entirely behind. In other words, no sophisticated art-historical explanations, and certainly no theology, allowed. At the Barnes, form is final. To adapt what Frank Sinatra said of New York City, if the notion that it was theologically principled Christians who invented art in the first place can make it here, it can make it anywhere.

I entered the Barnes as a skeptic. Many times I had visited the original museum in Merion, Pennsylvania, and I heard with considerable horror that this quirky Main Line mansion had succumbed to the fashion for sprawling modernist fortresses of refinement—the McMuseum. But when I finally found my way over an actual moat to the entrance, after getting my electronic ticket scanned no less than four times (one must boost the metrics), I was pleasantly surprised. The new Barnes so faithfully replicates the original home that I frequently couldn’t tell the difference.

Albert Barnes was able to amass his fortune through a pharmaceutical innovation that saved children from blindness. But unlike many of his big pharma successors, after healing physical eyes, Barnes took steps to heal our deeper perceptions as well. Barnes was able to compile one of the greatest collections of Post-Impressionist art in the world by amassing avant-garde French paintings before they became universally fashionable. He entrusted a high school classmate, William Glackens, with a ticket to Paris and bursting bankroll. Glackens, quite an artist in his own right, returned with an impressive collection of new work. Barnes, having now learned from Glackens to discern artistic excellence for himself, would never outsource his purchasing again.

Over the years, room after room of Barnes’s home was thereby enhanced with a stash of Cézannes, a pile of Picassos, a glut of Gauguins, and a vat of Van Goghs. In collaboration with the University of Chicago educator John Dewey, Barnes aimed to use these paintings not for art-historical trivia (naming the artists, regions, and periods) but to convey the experience of beauty, the education of sight. Hence, at the Barnes, that to which museumgoers predictably gravitate—the label—is mercilessly absent. One must instead actually look at the paintings, seeing how an iron hinge converses with a portrait of Hébuterne, which in turn responds to a healing of Lazarus.

The last item in that list might seem discordant. What are we to make of the ample Christian iconography in the putatively formalist Barnes Foundation? In the parlance of art, “formalism” evaluates paintings not by historical context and intellectual content but by form—colours, line, light, and space—instead. The Barnes believes in these categories so firmly that it even encourages viewers to search the collection through them. Because formalism ignores so much about art’s potential truth value, there is good reason this method has often been attacked. Indeed, to see a fleshy Renoir nude next to an innocent icon of the Virgin Mary is enough to exercise many a Christian. Should not the Mary be restored to its original function, leaving the pinups to the prurient? But thanks to the developments in aesthetic theory mentioned above, the hermeneutical current that overwhelms the sacred within the secular can be reversed. Christian iconography need not be neutered by formalism but can authorize aesthetic appreciation instead. Like Lausos the Christian admiring Aphrodite or Augustine counselling not to destroy a statue of Hercules, at the Barnes I felt no need to summon an American equivalent of Putin to forcefully return the Christian images in this collection to the Cathedral Basilica of Saints Peter and Paul across the street. To do so would be like offering premature furlough to a missionary, for each of the Christian images in this collection are missionaries in disguise. The Christian images offer necessary metaphysical cover so that other images can be appreciated for their aesthetic value alone. So it is that a vision of the clothed Virgin by El Greco offsets Van Gogh’s radiant though raunchy femme nue étendue sur un li.

Admittedly, this is a great offence to formalists. “Barnes was not a religious man!” they might insist. But this claim may be mistaken. The art world has long been filled with tales of Barnes’s storied resistance to art world elites. He did all he could in his lifetime to seal off his priceless collection from well-educated and wealthy “appreciators of art,” instead making it accessible only to the poor and disenfranchised. The novelist James Michener once had to pose as a janitor just to see the collection when Barnes was still alive. Art world admirers of Barnes would like to think this is an altruism derived from secular benevolence, but that would be to completely ignore Barnes’s lifelong connection to the Black Church.

It is likely that without the Black Church there would not be a Barnes Foundation today.

It all began in a camp meeting he attended when he was eight years old, and the effect of African American spirituals on Barnes’s soul never waned. Year after year Barnes had these spirituals performed in his home amid his priceless paintings, consecrating them over and over again. It was these spirituals, not just vague altruistic aspirations, that offered, in Barnes’s words, “the first step toward breaking down prejudice.” In effect, the Black Church is what accounts for Barnes’s lifelong tethering to the African American community that he did so much to educate, equip, and befriend. In fact, as with the influence of Harlem’s black congregations on Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s theology, it is likely that without the Black Church there would not be a Barnes Foundation today.

When these facts fall into place, every room of this eccentric collection begins to sing, almost as if the spirituals are still being performed. The Christians images are not aestheticized away; they authorize aestheticization. Tintoretto’s eucharistic feast next to a landscape by Renoir suggests that Christ will one day infuse everything the way he infuses bread and wine each Sunday. Jesus with the Samaritan woman by Horace Pippin is just below a woman by Jules Pascin whom we are invited to look on with the same intelligent compassion. An Annunciation by El Greco, where grey clouds are broken by a golden flow of mercy, is not diluted by its companion, a grey streetscape by Van Gogh. Instead, the juxtaposition enables Van Gogh’s painting to become a foretaste of the new Jerusalem. In a forgettable hay-strewn corridor, the future streets of gold are not just wishful dreaming but they perforate the present.

In another juxtaposition, a painting by Renoir of a woman with an assortment of hats is contrasted with a reverent assembly of women witnessing the Presentation of Mary in the temple. Hence, vainglorious display—a nineteenth-century version of Instagram—is overcome by the adventure into our internal holy of holies that we call contemplative prayer. Barnes deliberately put bad Renoirs next to better paintings to help viewers discern the difference. Accordingly, in one room, a not terribly successful Renoir surrounded by three pedestrian portraits is only a decoy—we are supposed to fix our eyes on the superior image of Mary being crowned by the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit nearby.

Let’s not kid ourselves about Modigliani’s Reclining Nude from the Back, as if a painting of such obvious sensuality offends modern sensibilities. The machines that bedevil the pockets of all her modern viewers offer images far more able to elicit lust; but unlike all of them, this unguarded rear end is shielded on three sides by vigilant Madonnas and on the fourth by a menacing piece of hardware that resembles a medieval chastity belt! Mary’s watchful eyes keep ours from descending into acquisitive desire. How convenient, by the way, to write that last line in our own era, when sexual desire has perilously and publicly unfurled into every imaginable concatenation, for this means the warning applies not only to heterosexual men like me but to anyone drawn to the intoxicating splendour of the shapely female form, not to mention the shapely form of men.

As for the Matisse mural that famously presides over the main room of the Barnes, it too is chastened, punctuated by statues of St. Barbara and the Madonna. Accordingly, Barnes’s Matisse is the real Matisse, the Matisse who constructed a chapel at the end of his life, the Matisse who wrote to his rival Picasso, “Yes, I pray, and so do you, and you know it: when everything goes badly, we throw ourselves into prayer, to rediscover the atmosphere of our first communion. And you do it, you do too.” It is this atmosphere that pervades the Barnes Foundation as well.

If the success of the Barnes Foundation as a venue for aesthetic appreciation is any indicator, faithful believers today who do not believe in the cult of art can make their way there, and indeed to each and every museum, with gladness and singleness of heart. There we will encounter no rival deities, but retired gods safely contained and defused by Christian iconography. Like the ancient Renaissance Christians who unearthed the Laocoön and concluded it must be admired rather than destroyed, so can we admire the beauty of these paintings today. Just as Barnes’s fortune bankrolled his great collection, so does the far greater Christian metaphysical fortune bankroll any experience of beauty in any museum, whether museumgoers realize it or not.

So, no, the Enlightenment did not invent the idea of art. Instead, it sundered art from the Christian matrix that had long enabled it to flourish, a matrix that—against the secularist’s hope—endures wherever Christian beauty graces institutional walls. As the secular cult of art dries up, the older sacred riverbed on which it flowed is increasingly exposed, which accounts for the irrepressible and ubiquitous discussions about religion in contemporary art today.

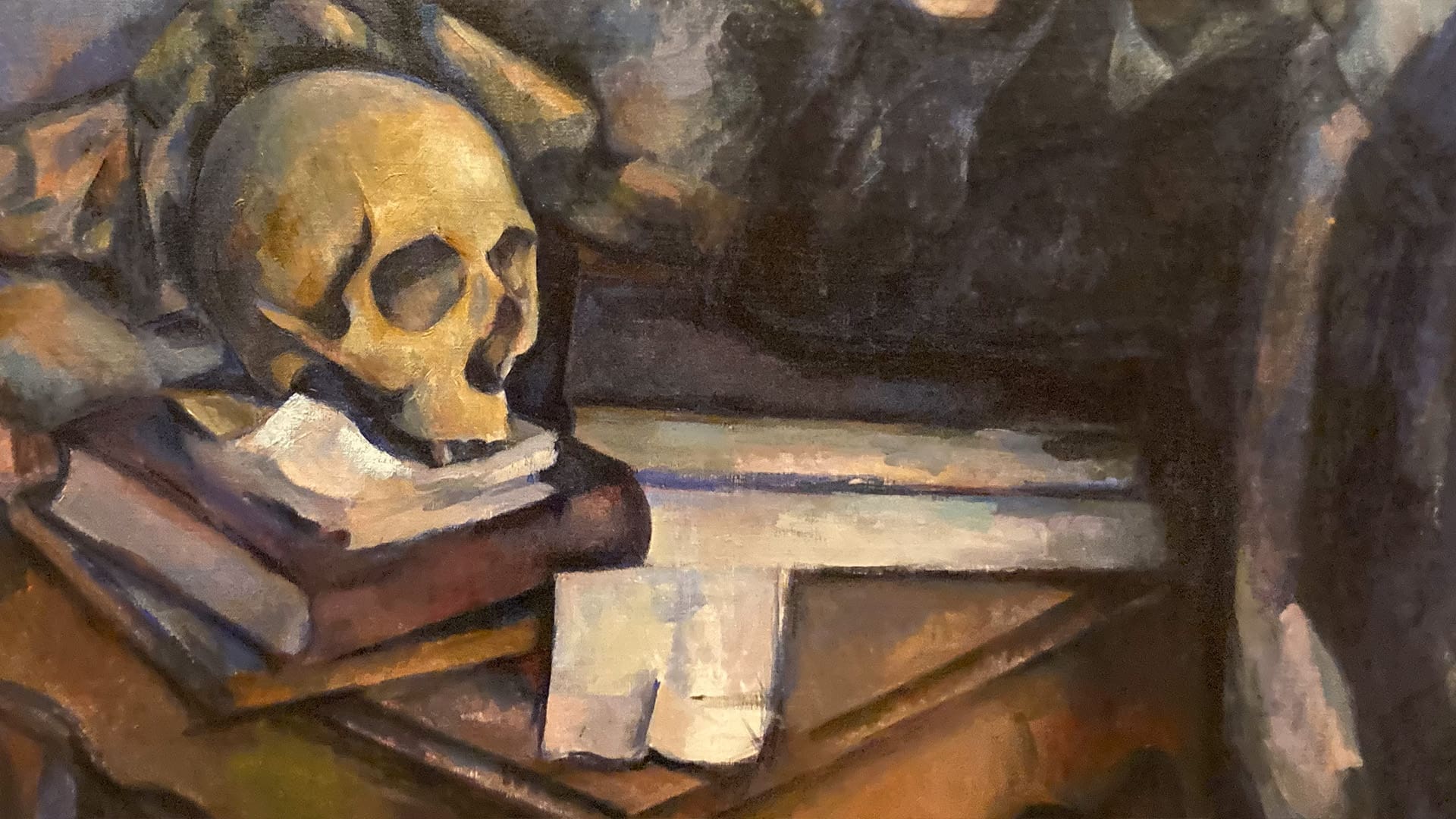

As to those for whom art endures as an alternative religion, take a cue from Cézanne at the Barnes, in what is perhaps the most beautiful skull he ever painted. Thanks to its proximity to an El Greco of Francis contemplating his mortality, Cezanne’s skull becomes the memento mori it was intended to be. Cézanne, who after returning to Catholicism midlife wanted his work to be “nothing but an absolutely faithful hymn of praise to the glory of God’s creation,” would have it no other way. So let this head spark new thoughts in your own. Should death be included in your future plans, don’t expect a curator or famous artist to visit your sickbed or to preside at your funeral. They have enough to do already. For all the titular bluffs and blustering, mortality vastly exceeds the expertise of art professionals, and you need to consider it. Entrusting your soul to a museum is like getting a Tesla serviced by a bike mechanic. Before or after visiting the museum, therefore, you might try attending a mosque, a temple, or—if you’re feeling especially transgressive—a Christian church.

I hear they don’t even charge admission.